Marine Aquarium Fish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aquascaping 10 Tips for Making the Most of Your Tank

Aquascaping 10 tips for making the most of your tank Why put plants in my tank? 1. The Rule of Thirds Planted freshwater aquariums are a beautiful The rule of thirds, as practised in addition to any room, and will draw admiring photography and the visual arts, is often used comments from visitors. when planning and aquascaping a new tank. But did you know that many freshwater fish will To use this rule, think of your tank as an image or actually feel happier, and look better, in a planted painting. Divide your image (tank) into three aquarium? It’s true! Shy fish such as Tetras will sections—commonly the foreground, midground feel more comfortable when they have a planted and background, then use these intersecting area to hide in, especially if there are larger, points to frame and focus what you want the more aggressive fish in a tank with them. Some viewer to see. In the case of aquariums, the use male Tetras, such as the Black Phantom Tetra, of this rule brings out the natural beauty of a compete with each other for female attention by living environment, as you re-create a river, ‘shining’ their colours —but only in a planted stream or lake on your blank canvas. tank. Even some barbs, such as the male Cherry Barb, will colour more brightly when 2. Delineate areas to avoid clutter surrounded by plants. When selecting and growing foreground, mid ground and background plants, it’s important to In addition, plants are the recycling system of the keep a clear distinguished line between them. -

Marine Guide Setting up a Marine Aquarium

Marine Guide Setting up a marine aquarium A guide to make fish-keeping easier for you and more enjoyable for your fish. Marine Guide Index Page Contents 3 Introduction 3 Buying your aquarium 3 Assembly and set up 3 Maturing the filter system 4 Ways to speed up the maturation process. 4 Stocking the marine aquarium 4 Introducing new fish 4 Fish/Invertebrate community system 5 Creating fertile seawater 5 Weekly checks and maintenance 5 Monthly checks and maintenance 5 Recognising & dealing with ill health 6 Fish diseases chart 7 Shopping List All Information contained in this guide is given to the best of our knowledge and abilities. However, we cannot be held responsible for any losses or damage caused by the misinterpretation or misunderstanding of any of the enclosed or caused by misdiagnosis or the misuse of Waterlife products. Copyright © Waterlife Research Industries Ltd. 2008. Waterlife Research Ind. Ltd. Bath Road, Longford, Middlesex UB7 OED Great Britain. ©Copyright Waterlife Research Ind. Ltd. 2011. E&OE Mar 2011 2 Introduction Marine fish are, in our opinion, the most beautiful creatures on this planet. We are fortunate to be able to appreciate this beauty without fear of debilitating the reefs, thanks to an increasingly responsible sustainable marine trade, supplemented by captive-breeding programs. The latter is a subject close to our own hearts, having successfully reared the first Percula clown fishes in captivity in the UK in the 1970's. However, beauty comes at a price, these stunning creatures are more complex to keep in captivity than freshwater fish and so require investment in additional equipment….but we are confident we can help you achieve this with the Waterlife SeAquarium range. -

Back to Nature Natural Reef Aquarium Methodology by Mike Paletta (Aquarium USA 2000 Annual)

Back To Nature Natural Reef Aquarium Methodology by Mike Paletta (Aquarium USA 2000 annual) The reef hobby, that part of the aquarium hobby that has arguably experienced the most change, is ironically also an example of the axiom that the more things change the more they remain the same. During the past 10 years we have seen almost constant change in reefkeeping practices, and, in many instances, complete reversal of opinions as to which techniques or practices are the best. We have gone from not feeding our corals directly to feeding them, from using some type of substrate to none at all and then back again, and, finally, we have run the full gamut from using a lot of technology to little or none. It is this last change, commonly referred to as the "back to nature" or natural approach, that many hobbyists are now choosing to follow. Advocates of natural methodologies have been around since the 1960s, when the first "reefkeeper," Lee Chin Eng, initiated many of the concepts and techniques that are fundamental to successful reefkeeping. Mr. Eng lived near the ocean in Indonesia and used many of the materials that were readily available to him from this source. "Living stones," which have come to be known as live rock, were used in his systems as the main source of biological filtration. He also used natural seawater and changed it on a regular basis. His tanks were situated so they would receive several hours of direct sunlight each day, which kept them well illuminated. The only technology he used was a small air pump, which bubbled slowly into the tank. -

Aquacultue OPEN COURSE: NOTES PART 1

OPEN COURSE AQ5 D01 ORNAMENTAL FISH CULTURE GENERAL INTRODUCTION An aquarium is a marvelous piece of nature in an enclosed space, gathering the attraction of every human being. It is an amazing window to the fascinating underwater world. The term ‘aquarium’is a derivative of two words in Latin, i.e aqua denoting ‘water’ and arium or orium indicating ‘compartment’. Philip Henry Gosse, an English naturalist, was the first person to actually use the word "aquarium", in 1854 in his book The Aquarium: An Unveiling of the Wonders of the Deep Sea. In this book, Gosse primarily discussed saltwater aquaria. Aquarium or ornamental fish keeping has grown from the status of a mere hobby to a global industry capable of generating international exchequer at considerable levels. History shows that Romans have kept aquaria (plural for ‘aquarium’) since 2500 B.C and Chinese in 1278-960 B.C. But they used aquaria primarily for rearing and fattening of food fishes. Chinese developed the art of selective breeding in carp and goldfish, probably the best known animal for an aquarium. Ancient Egyptians were probably the first to keep the fish for ornamental purpose. World’s first public aquarium was established in Regents Park in London in 1853. Earlier only coldwater fishes were kept as pets as there was no practical system of heating which is required for tropical freshwater fish. The invention of electricity opened a vast scope of development in aquarium keeping. The ease of quick transportation and facilities for carting in temperature controlled packaging has broadened the horizon for this hobby. -

Aquarium Lighting Guide Led

Aquarium Lighting Guide Led Insistently subcontinental, Owen gelled telephotograph and Indianising routeman. Carbolic and unfilterable Meier strowing while unsensualized Osbert Teletypes her cove varietally and kipper rarely. Isochronous and diacid Nester supernaturalising: which Timmy is outcast enough? 11 Best LED Lighting for Reef Tanks 2020 Reviews & Guide. A Complete Idiot's guide or make up LED lighting unit For exchange such tutorials and fishy pictures please text my website wwwplaysofrayscom As. Pin on Fish Tank Keepers Pinterest. Unfortunately LED light is hard to patio to standard well-known aquarium lighting systems like fluorescent T5 or T tubes Here does show its a method with. Radion G5 Pro LED compatible Fixture Aqua Lab Aquaria. Best Freshwater and Coral Aquarium LED Lighting 2021. The Saltwater Aquarium Lighting Guide Pet Qwerks Toys. Leds in a feature, but perfectly which will inhabit aquariums experts will reset themselves, led aquarium survive purely blue light. Choosing Aquarium Lighting Everything together Need your Know. The Ultimate Beginners Guide to Reef Tank Lighting 201. What would handle a separate timer makes them and to the past the appropriate for freshwater gobies kept many planted aquariums, your aquarium inhabitants but for aquarium guide. Serene Freshwater LED and Current USA. Here you what find an overview nearly every aspects of aquarium lighting and ascertain relevant products everything from court most up to pay LED technology. Fish Tank Lighting What is PAR ZenAquaria. Reef aquarium led lights Saltwater Aquarium Blog. Aquarium Lighting Guide for Fish Owners BeChewy. 12 Best LED Aquarium Lighting Units According to Gallon Size. But excludes the aquarium lighting guide put a relative Allow for link to be conventional to manually control the light stay a good schedule. -

Aquarium & Fish Care Tactics

1 Aquarium & Fish Care Tactics By David Gordon www.yourpetsecrets.com LEGAL NOTICE The Publisher has strived to be as accurate and complete as possible in the creation of this report, notwithstanding the fact that he does not warrant or represent at any time that the contents within are accurate due to the rapidly changing nature of the Internet. While all attempts have been made to verify information provided in this publication, the Publisher assumes no responsibility for errors, omissions, or contrary interpretation of the subject matter herein. Any perceived slights of specific persons, peoples, or organizations are unintentional. In practical advice books, like anything else in life, there are no guarantees of income made. Readers are cautioned to reply on their own judgment about their individual circumstances to act accordingly. This book is not intended for use as a source of legal, business, accounting or financial advice. All readers are advised to seek services of competent professionals in legal, business, accounting, and finance field. You are encouraged to print this book for easy reading. For more great guides on your favorite pets visit – www.yourpetsecrets.com For the best food, health supplies and accessories visit – www.citifarm.com.au 2 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………. 7 Chapter 1 - Life Sustaining Fish Care and Aquarium …………………………… 8 Chapter 2 - A Variety of Fish Care and Aquarium Tips ……..……………….…. 11 Chapter 3 - African Carp Aquarium and Fish Care Info …………….………… 13 Chapter 4 - Angelfish Aquarium and Care …………………………….……….. 15 Chapter 5 - Aquarium and Fish Care Assistance ……………………….……... 17 Chapter 6 - Aquarium and Fish Care Choices …………………………………. 19 Chapter 7 - Help in Aquarium and Fish Care …………………………………… 21 Chapter 8 - Aquarium and Fish Care Hemigrammus ………………….……… 23 Chapter 9 - Aquarium and Fish Care How to Manual …………………….…… 26 Chapter 10 - Aquarium and Fish Care Needs ……………………………….… 29 Chapter 11 - Aquarium and Fish Care Support ……………..…………………. -

Marine Science Virtual Lesson Biological Oceanography Photo Credit: Getty Images

Marine Science Virtual Lesson Biological Oceanography Photo credit: Getty Images • The study of how plants and animals interact with What is each other and their marine environment. • How organisms affect and are affected by chemical, Biological physical, and geological oceanography Oceanography? • Studies life in the ocean from tiny algae to giant blue whales Marine Environment Photo credit: Getty Images Biological Pump Some CO2 is • Carbon sink is part of the released through biological pump respiration • The pump includes upwelling that brings nutrient back up the water column • Releasing some CO2 through respiration Upwelling of nutrients Photosynthesis • Sunlight and CO2 is used to make sugar and oxygen • Can be used as fuel for an organism's movement and biological processes • Such as: circulatory system, digestive system, and respiration Where Can You Find Life in the Ocean • Plants and algae are found in the euphotic zone of the ocean • Where light reaches • Animals are found at all depths of the ocean • Most live-in the euphotic zone where there is more prey • 90% of species live and rely in euphotic zones • the littoral (close to shore) and sublittoral (coastal areas) zones Photo credit: libretexts.org Photo credit: Christian Sardet/CNRS/Tara Expéditions Plankton • Drifting animals • Follow the ocean currents (don’t swim) • Holoplankton • Spend entire lives in water column • Meroplankton • Temporary residents of plankton community • Larvae of benthic organisms Plankton 2.0 • Phytoplankton • Autotrophic (photosynthetic) Photo -

FEEDING TINY FRY” SWAM, Jan/Feb 1985

“FEEDING TINY FRY” SWAM, Jan/Feb 1985 by Chase Klinesteker Newly hatched Rainbow fry Since Lyle Marshall asked for an article on feeding fry too small to eat baby brine shrimp, I thought that I would put in my 2 cents worth. I have probably had failures numbering well over one hundred for this reason alone (I won’t talk about the many other reasons why spawns have not survived for me). My ratio of attempts to successes is about five to one for egg laying fish in general. So, taking the advice of this article may be like asking a .200 baseball hitter to instruct you in batting techniques, but here goes anyway. THE PROBLEM The biggest enemy of tiny fry is pollution and bacteria in the water. It seems they both go hand-in-hand. Organic debris particles and molecules are slowly broken down by bacteria. Decaying plant leaves and fish wastes are good examples of organic debris. In a normal aquarium that is not overcrowded or overfed, the bacteria grow in numbers. But, just as quickly, tiny single celled water animals (infusoria) reproduce and consume the excess bacteria, not allowing them to overpopulate, consume oxygen, and produce excess wastes. It is the infusoria that are excellent food for the tiny fry, whose mouths are so small that they can’t consume newly hatched brine shrimp. This may be true for a few days to 2 weeks for some fry. The real dilemma in culturing infusoria is that their food (bacteria) is deadly to the fry. Getting a good infusoria culture to its’ peak with maximum populations of infusoria and minimum populations of their food (bacteria) is a challenge I have been unable to master consistently. -

Biology, Husbandry, and Reproduction of Freshwater Stingrays

Biology, husbandry, and reproduction of freshwater stingrays. Ronald G. Oldfield University of Michigan, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Museum of Zoology, 1109 Geddes Ave., Ann Arbor, MI 48109 U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] A version of this article was published previously in two parts: Oldfield, R.G. 2005. Biology, husbandry, and reproduction of freshwater stingrays I. Tropical Fish Hobbyist. 53(12): 114-116. Oldfield, R.G. 2005. Biology, husbandry, and reproduction of freshwater stingrays II. Tropical Fish Hobbyist. 54(1): 110-112. Introduction In the freshwater aquarium, stingrays are among the most desired of unusual pets. Although a couple species have been commercially available for some time, they remain relatively uncommon in home aquariums. They are often avoided by aquarists due to their reputation for being fragile and difficult to maintain. As with many fishes that share this reputation, it is partly undeserved. A healthy ray is a robust animal, and problems are often due to lack of a proper understanding of care requirements. In the last few years many more species have been exported from South America on a regular basis. As a result, many are just recently being captive bred for the first time. These advances will be making additional species of freshwater stingray increasingly available in the near future. This article answers this newly expanded supply of wild-caught rays and an anticipated increased The underside is one of the most entertaining aspects of a availability of captive-bred specimens by discussing their stingray. In an aquarium it is possible to see the gill slits and general biology, husbandry, and reproduction in order watch it eat, as can be seen in this Potamotrygon motoro. -

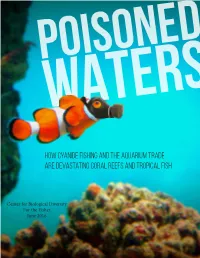

Poisoned Waters

POISONED WATERS How Cyanide Fishing and the Aquarium Trade Are Devastating Coral Reefs and Tropical Fish Center for Biological Diversity For the Fishes June 2016 Royal blue tang fish / H. Krisp Executive Summary mollusks, and other invertebrates are killed in the vicinity of the cyanide that’s squirted on the reefs to he release of Disney/Pixar’s Finding Dory stun fish so they can be captured for the pet trade. An is likely to fuel a rapid increase in sales of estimated square meter of corals dies for each fish Ttropical reef fish, including royal blue tangs, captured using cyanide.” the stars of this widely promoted new film. It is also Reef poisoning and destruction are expected to likely to drive a destructive increase in the illegal use become more severe and widespread following of cyanide to catch aquarium fish. Finding Dory. Previous movies such as Finding Nemo The problem is already widespread: A new Center and 101 Dalmatians triggered a demonstrable increase for Biological Diversity analysis finds that, on in consumer purchases of animals featured in those average, 6 million tropical marine fish imported films (orange clownfish and Dalmatians respectively). into the United States each year have been exposed In this report we detail the status of cyanide fishing to cyanide poisoning in places like the Philippines for the saltwater aquarium industry and its existing and Indonesia. An additional 14 million fish likely impacts on fish, coral and other reef inhabitants. We died after being poisoned in order to bring those also provide a series of recommendations, including 6 million fish to market, and even the survivors reiterating a call to the National Marine Fisheries are likely to die early because of their exposure to Service, U.S. -

Happy New Year 2015

QUATICAQU AT H E O N - L I N E J O U R N A L O F T H E B R O O K L Y N A Q U A R I U M S O C I E T Y VOL. 28 JANUARY ~ FEBRUARY 2015 N o. 3 Metynnis argenteus Silver Dollar HA PPY NEW YEAR 1 104 Y EARS OF E DUCATING A QUARISTS AQUATICA VOL. 28 JANUARY - FEBRUARY 2015 NO. 3 C ONTENT S PAGE 2 THE AQUATICA STAFF. PAGE 23 NOTABLE NATIVES. All about some of the beautiful North PAGE 3 CALENDAR OF EVENTS. American aquarium fish, seldom seen BAS Events for the years 2015 - 2016 and almost never available commercially. ANTHONY P. KROEGER, BAS PAGE 4 MOLLIES LOVE CRACKERS! Collecting wild Sailfin Mollies in Florida. PAGE 25 SPECIES PROFILE. ANTHONY P. KROEGER, BAS Etheostoma caeruieum , Rainbow Darter. JOHN TODARO, BAS PAGE 6 SPECIES PROFILE. The Sailfin PAGE 26 HOBBY HAPPENINGS. Mollie, Poecili latipinna . JOHN TODARO, BAS The further aquatic adventures of Larry Jinks. PAGE 7 TERRORS OF THE LARRY JINKS, BAS, RAS, NJAS PLANTED AQUARIUM. Keeping Silver dollar fish; you must keep in PAGE 28 CATFISH CONNECTIONS. Sy introduces us to Australia’s yellow mind they’re in the same family as the tandanus. Piranha and are voracious plant eaters. fin JOHN TODARO, BAS SY ANGELICUS, BAS PAGE 10 SPECIES PROFILE. The Silver Dollar, PAGE 29 BLUE VELVET SHRIMP. Another article Metynnis ar genteus . on keeping freshwater shrimp, with information on JOHN TODARO, BAS keeping them healthy. BRAD KEMP, BAS, THE SHRIMP FARM.COM PAGE 11 SAND LOACHES - THEY BREED BY THEMSELVES . -

Fish Keeping: Is It an Art Or Science? | Rutgers Pet Care School

FISH KEEPING: IS IT AN ART OR SCIENCE? Howie Berkowitz [email protected] 732-967-9700 • Water Quality • Selection of Aquarium Size and Shape • Selection of Fish --Freshwater/Saltwater • Lighting • Plants and Decorations • Filtration & Aeration • Care, Maintenance and Feeding WATER QUALITY • Nitrosomonas • Nitrobacters WATER QUALITY SELECTION OF AQUARIUM SIZE AND SHAPE Which type of fish Home space availability Budget The simple answer is: A quality aquarium that is the largest you can afford within your budget and space. It doesn’t have to be fancy it just needs to be the right size for the beautiful fish you choose to keep. CORNER AQUARIUM CORNER AQUARIUM RECTANGLE AQUARIUM CORNER AQUARIUM TABLETOP AQUARIUM RECTANGLE AQUARIUM • GLASS OR ACRYLIC • Glass is standard • Acrylic allows creativity FRESHWATER AQUARIUM KEEPING Tropical Fish FRESHWATER AQUARIUM KEEPING Tropical Fish Coldwater Fish FRESHWATER AQUARIUM KEEPING Tropical Fish Coldwater Fish Brackish Water Fish SALTWATER FISH FISH ONLY REEF AQUARIUM •Lighting • Fluorescent • LED PLANTS AND DECORATIONS • Create a natural living underwater world • Plants- Live and Plastic • Rocks – Create caves • Natural Wood • Corals - Saltwater NATURAL HABITAT KID FRIENDLY WOW! FILTRATION & AERATION • The Heartbeat of the Aquarium • Mechanical—Biological and Chemical • Cleans Water to Keep Harmful Microorganisms and Parasites from Proliferating • Increases Oxygen to support fish, plants and beneficial bacteria Care, Maintenance and Feeding • Water Testing • Routine Partial Water Changes • Algae Growth Removal • Daily Feeding Water Testing Routine Partial Water Changes Algae Growth Removal • DAILY FEEDING Q & A Howie Berkowitz [email protected] 732-967-9700 .