An Overview of the Archaeology of Mendip Caves and Karst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repeated Dye Traces of Underground Streams in the Mendip Hills, Somerset

47 Proc. Univ., Bristol Spelaeol. Soc, 1981. 16 (1). 47-58 REPEATED DYE TRACES OF UNDERGROUND STREAMS IN THE MENDIP HILLS. SOMERSET by W. I. STANTON and P. L. SMART ABSTRACT Three underground streams were dye traced as many as twenty-four times, at various Hows between the extremes of Hood and drought. This systematic study, the first of its kind to our knowledge, has shown that: 1. Travel time (the time between input of dye at the swallet and its first arrival at the resurgence) is inversely proportional (1:1) to mean resurgence outpul over the same period. This is characteristic of simple phreatie streams, which should be distinguishable using graphic analysis from vadose and complex phrcatic streams. 2. Rhodamine WT dye. the most stable of the common fluorescent dyes, Ls progress ively lost, to a significant and unpredictable extent, in transit from swallci to resurgence. Successful tracing therefore requires more dye at low flows than at high flows. BACKGROUND Water tracing in the Mendip caves has a long and distinguished history (Barrington and Stanton 1977, 209-213). The early experimenters, beginning at Wookey Hole Cave (ST 532.480) in 1860, used chaff, dyes or coloured powders, hoping for results visible to the naked eye. The modern phase of water tracing began in 1965 using the spores of a moss, Lycopodium clavatum, which were flushed down the swallets and caught at the resurgences in plankton nets. For the first time the tracing agent could not be detected by the unaided senses, and some attempt at quantitative analysis of results could be made (Atkinson, Drew and High 1967; Drew, Newson and Smith 1968). -

The Wessex Cave Club Journal Volume 24 Number 261 August 1998

THE WESSEX CAVE CLUB JOURNAL VOLUME 24 NUMBER 261 AUGUST 1998 PRESIDENT RICHARD KENNEY VICE PRESIDENTS PAUL DOLPHIN Contents GRAHAM BALCOMBE JACK SHEPPARD Club News 182 CHAIRMAN DAVE MORRISON Windrush 42/45 Upper Bristol Rd Caving News 182 Clutton BS18 4RH 01761 452437 Swildon’s Mud Sump 183 SECRETARY MARK KELLAWAY Ceram Expedition 183 5 Brunswick Close Twickenham Middlesex NCA Caver’s Fair 184 TW2 5ND 0181 943 2206 [email protected] Library Acquisitions 185 TREASURER & MARK HELMORE A Fathers Day To Remember 186 MRO CO-ORDINATOR 01761 416631 EDITOR ROSIE FREEMAN The Rescue of Malc Foyle 33 Alton Rd and His Tin Fish 187 Fleet Hants GU13 9HW Things To Do Around The Hut 189 01252 629621 [email protected] Observations in the MEMBERSHIP DAVE COOKE St Dunstans Well and SECRETARY 33 Laverstoke Gardens Ashwick Drainage Basins 190 Roehampton London SW15 4JB Editorial 196 0181 788 9955 [email protected] St Patrick’s Weekend 197 CAVING SECRETARY LES WILLIAMS TRAINING OFFICER & 01749 679839 Letter To The Membership 198 C&A OFFICER [email protected] NORTHERN CAVING KEITH SANDERSON A Different Perspective 198 SECRETARY 015242 51662 GEAR CURATOR ANDY MORSE Logbook Extracts 199 HUT ADMIN. OFFICER DAVE MEREDITH Caving Events 200 HUT WARDEN ANDYLADELL COMMITTEE MEMBER MIKE DEWDNEY-YORK & LIBRARIAN WCC Headquarters, Upper Pitts, Eastwater Lane SALES OFFICER DEBORAH Priddy, Somerset, BA5 3AX MORGENSTERN Telephone 01749 672310 COMMITTEE MEMBER SIMON RICHARDSON © Wessex Cave Club 1998. All rights reserved ISSN 0083-811X SURVEY SALES MAURICE HEWINS Opinions expressed in the Journal are not necessarily those of the Club or the Editor Club News Caving News Full details of the library contents are being Swildon’s Forty - What was the significance of the painstakingly entered by the Librarian onto the 10th July this year? WCC database. -

Pleistocene Rodents of the British Isles

PLEISTOCENE RODENTS OF THE BRITISH ISLES BY ANTONY JOHN SUTCLIFFE British Museum (Natural History), London AND KAZIMIERZ KOWALSKI Institute of Systematic and Experimental Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Krakow, Poland Pp. 31-147 ; 31 Text-figures ; 13 Tables BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM (NATURAL HISTORY) GEOLOGY Vol. 27 No. 2 LONDON: 1976 THE BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM (natural history), instituted in 1949, is issued in five series corresponding to the Scientific Departments of the Museum, and an Historical series. Parts will appear at irregular intervals as they become ready. Volumes will contain about three or four hundred pages, and will not necessarily be completed within one calendar year. In 1965 a separate supplementary series of longer papers was instituted, numbered serially for each Department. This paper is Vol. 27, No. 2, of the Geological [Palaeontological) series. The abbreviated titles of periodicals cited follow those of the World List of Scientific Periodicals. World List abbreviation : Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist. (Geol. ISSN 0007-1471 Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), 1976 BRITISH MUSEUM (NATURAL HISTORY) Issued 29 July, 1976 Price £7.40 . PLEISTOCENE RODENTS OF THE BRITISH ISLES By A. J. SUTCLIFFE & K. KOWALSKI CONTENTS Page Synopsis ........ 35 I. Introduction ....... 36 A. History of Studies ..... 37 B. The Geological Background .... 40 II. Localities in the British Isles with fossil rodents 42 A. Deposits OF East Anglia . .... 42 (i) Red Crag 43 (ii) Icenian Crag ....... 43 (iii) Cromer Forest Bed Series ..... 46 (a) Pastonian of East Runton and Happisburgh 47 (b) Beestonian ...... 48 (c) Cromerian, sensu stricto .... 48 (d) Anglian ...... -

A Wild Land Ready for Adventure the Mendip Hills

oS ExPlorEr maP oS ExPlorEr maP oS ExPlorEr maP oS ExPlorEr maP 141 141 154 153 GrId rEfErEnCE GrId rEfErEnCE GrId rEfErEnCE GrId rEfErEnCE A WILD LAND E Guid or T Visi St 476587 ST466539 St578609 St386557 POSTCODE POSTCODE POSTCODE POSTCODE READY FOR BS40 7au Car Park at tHE Bottom of BS27 3Qf Car Park at tHE Bottom BS40 8tf PICnIC and VISItor faCIlItIES, BS25 1DH kInGS Wood CAR Park BurrInGton ComBE of tHE GorGE nortH EaSt SIdE of lakE AdvENTURE BLACK DOWN & BURRINGTON HAM CHEDDAR GORGE CHEW VALLEY LAKE CROOK PEAK Courtesy of Cheddar Gorge & Caves This area is a very special part of Mendip.Open The internationally famous gorge boasts the highest Slow down and relax around this reservoir that sits in The distinctive peak that most of us see from the heathland covers Black Down, with Beacon Batch at inland limestone cliffs in the country. Incredible cave the sheltered Chew Valley. Internationally important M5 as we drive by. This is iconic Mendip limestone its highest point. Most of Black Down is a Scheduled systems take you back through human history and are for the birds that use the lake and locally loved by the countryside, with gorgeous grasslands in the summer ENTURE dv A Monument because of the archaeology from the late all part of the visitor experience. fishing community. and rugged outcrops of stone to play on when you get Stone Age to the Second World War. to the top. Travel on up the gorge and you’ll be faced with Over 4000 ducks of 12 different varieties stay on Y FOR FOR Y D REA Burrington Combe and Ham are to the north and adventure at every angle. -

St Laurence Bronze Assessed Joining Instructions

St Laurence Bronze Assessed Expedition 18th and 19th June 2021 Joining Instructions for Parents and Participants Please read these carefully to ensure we get everyone to the right place at the right time with the right kit The weekend will be run as far as is possible to replicate a DofE Bronze assessed expedition without the camping element. Participants will still be expected to carry full expedition kit, please see kit list for advice on the following. On both days groups will walk independently of an instructor but under distance supervision, times for pick up are assumed, we are assuming groups will stick to the times they have planned, navigate without mistakes and cover ground at the assumed rate. Kit to carry and wear • Boots that must cover the ankle bone with good walking socks. • Walking ( preferably non cotton ) clothing to wear and a full change in a waterproof bag to carry inside the rucksack. No shorts ( ticks are bad in the Mendips ), no strappy tops, proper sports leggings are acceptable but walking trousers are preferable. • Sleeping bag ( In a compression sack and waterproof bag ) and roll mat • Waterproof Jacket and Trousers ( No matter what the forecast ) • A Sunhat and sun cream ( no exceptions here unless on specified medical grounds ) • Full size expedition rucksack ( group kit will have to be carried ) • A substantial packed lunch, 2 Ltrs of water ( minimum ) and the ingredients to make a hot drink on the stove. Participants should also ensure they have a very good breakfast on the day before leaving the house. • Any Covid compliant equipment as specified by the school but certainly all participants should bring an appropriate mask and a small bottle of hand sanitizer. -

Long, W, Dedications of the Somersetshire Churches, Vol 17

116 TWENTY-THIKD ANNUAL MEETING. (l[ki[rk^. BY W, LONG, ESQ. ELIEVING that a Classified List of the Dedications jl:> of the Somersetshire Churches would be interesting and useful to the members of the Society, I have arranged them under the names of the several Patron Saints as given by Ecton in his “ Thesaurus Kerum Ecclesiasticarum,^^ 1742 Aldhelm, St. Broadway, Douiting. All Saints Alford, Ashcot, Asholt, Ashton Long, Camel West, Castle Cary, Chipstaple, Closworth, Corston, Curry Mallet, Downhead, Dulverton, Dun- kerton, Farmborough, Hinton Blewitt, Huntspill, He Brewers, Kingsdon, King Weston, Kingston Pitney in Yeovil, Kingston] Seymour, Langport, Martock, Merriot, Monksilver, Nine- head Flory, Norton Fitzwarren, Nunney, Pennard East, PoLntington, Selworthy, Telsford, Weston near Bath, Wolley, Wotton Courtney, Wraxhall, Wrington. DEDICATION OF THE SOMERSET CHURCHES. 117 Andrew, St. Aller, Almsford, Backwell, Banwell, Blagdon, Brimpton, Burnham, Ched- dar, Chewstoke, Cleeve Old, Cleve- don, Compton Dundon, Congresbury, Corton Dinham, Curry Rivel, Dowlish Wake, High Ham, Holcombe, Loxton, Mells, Northover, Stoke Courcy, Stoke under Hambdon, Thorn Coffin, Trent, Wells Cathedral, White Staunton, Withypool, Wiveliscombe. Andrew, St. and St. Mary Pitminster. Augustine, St. Clutton, Locking, Monkton West. Barnabas, St. Queen’s Camel. Bartholomew, St. Cranmore West, Ling, Ubley, Yeovilton. Bridget, St. Brean, Chelvy. Catherine, St. Drayton, Montacute, Swell. Christopher, St. Lympsham. CONGAR, St. Badgworth. Culborne, St. Culbone. David, St. Barton St. David. Dennis, St. Stock Dennis. Dubritius, St. Porlock. Dun STAN, St. Baltonsbury. Edward, St. Goathurst. Etheldred, St. Quantoxhead West. George, St. Beckington, Dunster, Easton in Gordano, Hinton St. George, Sand- ford Bret, Wembdon, Whatley. Giles, St. Bradford, Cleeve Old Chapel, Knowle St. Giles, Thurloxton. -

Saints, Monks and Bishops; Cult and Authority in the Diocese of Wells (England) Before the Norman Conquest

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 3 Issue 2 63-95 2011 Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen University of Bristol Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Costen, Michael. "Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3, 2 (2011): 63-95. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol3/iss2/4 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Costen Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen, University of Bristol, UK Introduction This paper is founded upon a database, assembled by the writer, of some 3300 instances of dedications to saints and of other cult objects in the Diocese of Bath and Wells. The database makes it possible to order references to an object in many ways including in terms of dedication, location, date, and possible authenticity, and it makes data available to derive some history of the object in order to assess the reliability of the information it presents. -

72011 Land at Hort Bridge, Ilminster, Somerset.Pdf

Wessex Archaeology Land at Hort Bridge Ilminster, Somerset Archaeological Field Evaluation Report Ref: 72011.03 October 2009 LAND AT HORT BRIDGE, ILMINSTER, SOMERSET Archaeological Field Evaluation Report Prepared for Alchemy Properties Building 5100 Cork Airport Business Park Kinsale Road Cork by Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 72011.03 October 2009 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2009 all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Hort Bridge, Ilminster Alchemy Properties LAND AT HORT BRIDGE, ILMINSTER, SOMERSET Archaeological Field Evaluation Report Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background .....................................................................................1 2 THE SITE.............................................................................................................1 2.1 Location, topography and geology ..............................................................1 3 ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ...............................2 3.1 Introduction..................................................................................................2 3.2 Environmental Assessment.........................................................................2 3.3 Geophysical Survey ....................................................................................4 4 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................4 -

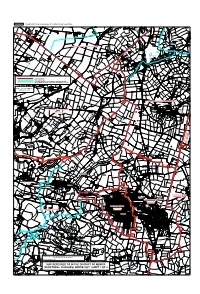

Map Referred to in the District of Mendip

SHEET 3, MAP 3 Mendip District. Wards and parish wards in St Cuthbert Out and Shepton Mallet Emborough Quarries Shooter's Bottom Farm d n NE U A Emborough Grove L AY W CHEWTON MENDIP CP RT PO Green Ore B 3 1U 3n 5d Portway Downside Bridge CHILCOMPTON CP D ef CHEWTON MENDIP AND STON EASTON WARD E N A L T R Dalleston U O C 'S R E EMBOROUGH CP N R BINEGAR CP U T Binegar Green Gurney Slade Quarry Binegar VC, CE (Stone) Primary School Gurney Slade Hillgrove Farm Binegar Binegar Quarry (disused) T'other Side the Hill NE Tape Hill LA T'S ET NN BE Def Kingscombe D ef KEY Highcroft Quarry (disused) WARD BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH OTHER BOUNDARIES PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY PW Ashwick R O E Cemetery ME A Scale : 1cm = 0.10000 km D Gladstone Villas L A N Grid interval 1km E Haydon f e D Horrington Hill D ef Reservoirs (covered) d n ASHWICK, CHILCOMPTON AND STRATTON WARD U Poultry Houses Recreation Ground ASHWICK CP West Horrington ST CUTHBERT OUT NORTH WARD Oakhill Little London Oakhill Manor Oakhill CE (V.C.) Oakhill CE (V.C.) Primary SchoolPrimary School All Saints' Church ST CUTHBERT OUT EAST All Saints' Church PARISH WARD Golf Course d n U Horrington County Nursery Primary School O LD FR O D M ef E R O De A f D D ef D i s East Horrington m a n t l e E ST CUTHBERT OUT CP Washingpool d f N e R A D a L i l E w P a U y f R e D H T D ef D D R South Horrington N A A P C W D L R E E A High Ridge B O H F M C I E O M L C T S O L D E C r O iv E K in N g A H O L R T a L n L S g e E N Beacon Hill P A -

Mining the Mendips

Walk Mining the Mendips Discover the hidden history of a small Mendips village Black Down in winer © Andrew Gustar, Flickr (CCL) Time: 3 hours Distance: 6 miles Landscape: rural Welcome to the Mendips in Somerset. This is Location: an area of limestone escarpments and open Shipham, Somerset countryside; with rich and varied scenery, magnificent views and a fascinating history. Start: The Square, Shipham BS25 1TN Discover why the area’s curious geology made Finish: this a centre of lead and zinc mining and find Lenny’s Cafe out how the lives of villagers changed during the ‘boom and bust’ stages of Mendip’s mining Grid reference: past. ST 44416 57477 Rich resources need defending and this walk Keep an eye out for: will take you on a journey through the past Wonderful views of the Bristol Channel and its islands from an Iron Age hill fort to the remains of a fake decoy town designed to distract German bombers away from Bristol. Thank you! This walk was created by Andrew Newton, a Fellow of The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) Every landscape has a story to tell – find out more at www.discoveringbritain.org Route and stopping points 01 Shipham Square 02 Layby on Rowberrow Lane 03 The Swan Inn, Rowberrow Lane 04 Rowberrow Church 05 Dolebury Warren Iron Age Hill Fort 06 Junction between bridleway to Burrington Combe and path to Black Down 07 Black Down 08 Starfish Control Bunker 09 Rowberrow Warren Conifer plantation 10 The Slagger’s Path 11 Gruffy Ground 12 St Leonard’s Church 13 Lenny’s Café Every landscape has a story to tell – Find out more at www.discoveringbritain.org 01 Shipham Square Welcome to the Mendips village of Shipham. -

BRSUG Number Mineral Name Hey Index Group Hey No

BRSUG Number Mineral name Hey Index Group Hey No. Chem. Country Locality Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-37 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Basset Mines, nr. Redruth, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-151 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Phoenix mine, Cheese Wring, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-280 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 County Bridge Quarry, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and South Caradon Mine, 4 miles N of Liskeard, B-319 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-394 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 ? Cornwall? Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-395 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-539 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Houghton, Michigan Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-540 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan, Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-541 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan, Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, -

The Sandford Gulf and Other Lost Caves of Sandford Hill

THE SANDFORD GULF AND OTHER LOST CAVES OF SANDFORD HILL By R. M. Taviner During the 18 th century, miners’ working on the western outliers of the Mendip Hills intercepted several small but notable cave systems, including the Banwell caves, Loxton Cavern and Hutton Cavern. Most were subsequently lost, although several have recently been rediscovered by cave explorers, often by following clues provided by the antiquarians who dutifully recorded them. Not all of these caverns have been rediscovered however, including three well documented sites on Sandford Hill. The first, Elephant Cave - which contained the skeleton of a full sized elephant - was recorded in 1770, while the better documented Sandford Bone Fissure was excavated by William Beard, beginning in 1837. Both of these sites are important, but it is the third lost cave, the legendary Sandford Gulf, that most exercises the minds of cavers. It is hoped that this article will help to bring some clarity to proceedings, and through a process of elimination, propose a precise location for the missing Gulf - a very good place to start digging! Sandford Hill from the North-West Map data ©2016 Google ELEPHANT CAVE The full details of this mysterious cave were included in a letter dated 30 th January 1770, sent by William Jeffries of Wrington to The Rev. Alexander Catcott, clergyman, geologist and author of A Treatise on the Deluge. ‘Where these Bones were found in almost the highest part of the Hill on the north Side: they lay in an East and West Direction four fathom deep in a loose Strata composed mostly of small Fragments of limestone, Sand etc.