A Short History of the Athlone Fellowship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EJ Air Pollution

www.spireresearch.com Air Pollution China’s public health danger © 2007 Spire Research and Consulting Pte Ltd Air Pollution – China’s public health danger The rapid pace of economic growth in the Asia Pacific region has been accompanied by resource depletion and environmental degradation. Air is the first element to get tainted by industrialization, with air quality becoming an increasingly important public health issue. China in particular has grappled with air pollution and frequent bouts of “haze” in recent years. Chinese smog has been recorded not only in Hong Kong but as far afield as America and Europe. Spire takes a look at how this impacts government, business and society. Air raid The Great Smog of London in December 1952 caused over 4,000 deaths, a result of rapid industrialization and urbanization. Dr Robert Waller, who worked at St Bartholomew's Hospital in the early 1950s, believed that a shortage of coffins and high sales of flowers were the first indications that many people were being killed. "The number of deaths per day during and just after that smog was three to four times the normal level," he said. Figure 1: Death rate with concentrations of The smog, which lasted for five days, smoke was so bad that it infiltrated hospital wards. The death toll was not disputed by the authorities, but exactly how many people perished as a direct result of the fog is unknown. Many who died already suffered from chronic respiratory or cardiovascular complaints. Without the fog, though, they might not have died so early. Mortality from bronchitis and pneumonia increased more than seven-fold as a result of the fog (see Figure 1). -

'And Plastic Servery Unit Burns

Issue number 103 Spring 2019 PLASTIC SERVERY ’AND BURNS UNIT GIFT SUGGESTIONS FROM The East India Decanter THE SECRETARY’S OFFICE £85 Club directory Ties The East India Club Silk woven tie in club Cut glass tumbler 16 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LH colours. £20 Telephone: 020 7930 1000 Engraved with club Fax: 020 7321 0217 crest. £30 Email: [email protected] Web: www.eastindiaclub.co.uk The East India Club DINING ROOM – A History Breakfast Monday to Friday 6.45am-10am by Charlie Jacoby. Saturday 7.15am-10am An up-to-date look at the Sunday 8am-10am characters who have made Lunch up the East India Club. £10 Monday to Friday 12.30pm-2.30pm Sunday (buffet) 12.30pm-2.30pm (pianist until 4pm) Scarf Bow ties Saturday sandwich menu available £30 Tie your own and, Dinner for emergencies, Monday to Saturday 6.30pm-9.30pm clip on. £20 Sundays (light supper) 6.30pm-8.30pm Table reservations should be made with the Front The Gentlemen’s Desk or the Dining Room and will only be held for Clubs of London Compact 15 minutes after the booked time. New edition of mirror Pre-theatre Anthony Lejeune’s £22 Let the Dining Room know if you would like a quick Hatband classic. £28 V-neck jumper supper. £15 AMERICAN BAR Lambswool in Monday to Friday 11.30am-11pm burgundy, L, XL, Saturday 11.30am-3pm & 5.30pm-11pm XXL. £55 Sunday noon-4pm & 6.30pm-10pm Cufflinks Members resident at the club can obtain drinks from Enamelled cufflinks the hall porter after the bar has closed. -

Hurlingham Club, London UK

Hurlingham Club, London UK About The Club Restrictions on reciprocal club members visits? Bordering the Thames in Fulham and set in 42 acres of Members of reciprocal clubs may visit The Hurlingham Club 14 magnificent grounds, The Hurlingham Club is a green times in any one calendar year. Letter of introduction required. oasis of tradition and international renown. Recognised On each occasion before use of the Club, an Overseas throughout the world as one of Britain’s greatest private Reciprocal Member must show current proof of their Overseas members’ clubs, it retains its quintessentially English Reciprocal Club membership, including a letter of introduction traditions and heritage, while providing modern facilities dated no more than 4 months prior to the date of admission to the and services for its members. The Club continually looks Club and photo ID. The letter of introduction must confirm the at ways in which it can improve, for both current and Reciprocal Member’s current Membership status, and non UK future generations, the first-class social and sporting residency. They must sign in the book provided at the Gatehouse facilities within an elegant and congenial ambience. and include the names of any accompanying guests. Contact Information Facilities Ranelagh Gardens Reading room, fitness centre, golf, swimming pool, tennis, bowls, London SW6 3PR croquet. Games, including chess, scrabble, backgammon and sets of boules are available for use in the Clubhouse and grounds. Tel: (0044) 20 7736 8411 Email: [email protected] Parking Web: http://www.hurlinghamclub.org.uk/ The main car park for the Clubhouse is the horseshoe car park, located near main reception, however there are a number of other Club Hours car parks throughout the estate (refer website for map). -

MICKY STEELE-BODGER In

Issue number 104 Summer 2019 EXPLOSIVE GENEROUS TOUGH LOYAL FROM THE HIP GIFT SUGGESTIONS FROM The East India Decanter THE SECRETARY’S OFFICE £85 Club directory Ties The East India Club Silk woven tie in club Cut glass tumbler 16 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LH colours. £20 Telephone: 020 7930 1000 Engraved with club Fax: 020 7321 0217 crest. £30 Email: [email protected] Web: www.eastindiaclub.co.uk The East India Club DINING ROOM – A History Breakfast Monday to Friday 6.45am-10am by Charlie Jacoby. Saturday 7.15am-10am An up-to-date look at the Sunday 8am-10am characters who have made Lunch up the East India Club. £10 Monday to Friday 12.30pm-2.30pm Sunday (buffet) 12.30pm-2.30pm (pianist until 4pm) Scarf Bow ties Saturday sandwich menu available £30 Tie your own and, Dinner for emergencies, Monday to Saturday 6.30pm-9.30pm clip on. £20 Sundays (light supper) 6.30pm-8.30pm The Gentlemen’s Table reservations should be made with the Front Compact mirror Desk or the Dining Room and will only be held for Clubs of London 15 minutes after the booked time. New edition of £22 Pre-theatre Anthony Lejeune’s V-neck jumper Let the Dining Room know if you would like a Hatband classic. £28 Lambswool in navy or quick supper. £15 burgundy, M (navy only), L, AMERICAN BAR XL, XXL. £57 Monday to Friday 11.30am-11pm Saturday 11.30am-3pm & 5.30pm-11pm Sunday noon-4pm & 6.30pm-10pm Cufflinks Members resident at the club can obtain drinks from Enamelled cufflinks the hall porter after the bar has closed. -

Fundraisingautumn 2016 7 01 2017

Fundraising news Winter 2016 Exciting times in the search for Barth syndrome treatments At a recent information day held by the Barth Syndrome Trust (BST), led by Michaela Damin with Prof Steward, families learnt about prospective research projects and clinical trials, and how they could participate in the search for one or more treatments. There is still a long way to go, but this is a start and to get this far is a truly amazing achievement. Several of our families have taken part in research already. Yet where we are today and where we hope to go in the pursuit of treatments would not be possible without the dedication and hard work of our wonderful families, friends, donors and fundraisers, who have through the years believed in us. The following pages outline your fundraising efforts, that are both humbling and inspiring. >>>>>> Thank you to each and every one of you. Fundraising news in brief Donations and Standing Orders Sarah Whithorn © Many of our friends and families contribute monthly © £50 - proceeds from a Tuck Shop run at work by standing orders. We have also received donations Finkley Down Farm, Andover from work colleagues, friends and families in UK, © Thank you to Charles Waters, the staff and visitors Belgium and The Netherlands. See page 6. at Finkley Down Farm for their generosity. They Julie Woolley and Friends hold the record for the largest amount collected in © Collecting box: £94.64 one of our boxes. So far in 2016 they have donated © Raffle by Wilf and Brenda Smith: £135 £191 and have collected an amazing £558 in total since they first started displaying our collection First Steps Pre-School, Bramhope, Leeds box. -

1 Fighting Smog in Los Angeles the Air Pollution Was So Thick You Could

Fighting Smog in Los Angeles The air pollution was so thick you could cut it with a knife. I remember looking at the outside window and saying, “Oh my, there’s the smog.” Here we are. You should be able to see the mountains, you should be able to see our beautiful city, but you can’t see anything. And it’s destroying not only our health. But our economy. From 50 to 70 percent of the junk that’s in the air comes from our own cars. Mine and yours. Alexis: Hi, I’m Alexis Pedrick. Lisa: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago, and this is Distillations, coming to you from the Science History Institute. Alexis: Each episode of Distillations takes a deep dive into a moment of science-related history in order to shed some light on the present. Today we’re talking about smog in Los Angeles, in the final installment of a three-part series about environmental success stories. Lisa: Our last two episodes, “Whatever Happened to the Ozone Hole?” and “Whatever Happened to Acid Rain?” are available on our website: Distillations DOT ORG, through Apple Podcasts, or wherever else you get your podcasts! Alexis: If you live in Los Angeles, or even if you’ve just visited, you know all about smog. But what you might not know is that half a century ago smog in Los Angeles was already completely unbearable even though they had far fewer cars. As of June 2018, the United States has one of the strictest car emission standards in the world. -

Reviews Summer 2019

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Jones, E, et al. 2019. Reviews Summer 2019. Architectural Histories, 7(1): 17, pp. 1–10. +LVWRULHV DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.429 REVIEW Reviews Summer 2019 Emma Jones, Carole Pollard, Mari Lending, and Ani Kodzhabasheva Jones, E. A review of Kurt W. Forster, Schinkel: A Meander Through His Life and Work, Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag, 2018. Pollard, C. A review of Susan Galavan, Dublin’s Bourgeois Homes: Building the Victorian Suburbs, 1850– 1901, London: Routledge, 2018. Lending, M. A review of Lynn Meskell, A Future in Ruins: UNESCO, World Heritage, and the Dream of Peace, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2018, and Lucia Allais, Designs of Destruction: The Making of Monuments in the Twentieth Century, Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 2018. Kodzhabasheva, A. A review of Robin Schuldenfrei, Luxury and Modernism: Architecture and the Object in Germany 1900–1933, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018. Meandering Through Schinkel are in many ways as immensely personal as they are informative. The personal emerges immediately through Emma Jones Forster’s lyrical essayistic prose, which contains frequent Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, CH conjectures, contradictions, asides, and diversions from [email protected] the main argument that reveal something of the char- acter and interests of the writer; while the informative Kurt W. Forster, Schinkel: A Meander Through His Life and Work, Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag, 411 pages, 2018, ISBN: 9783035607789. A meander, signifying an indirect or aimless journey, could be considered a curious choice for inclusion in the title of a book about the life and work of Prussia’s most pro- lific and industrious architect, Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781–1841). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Bourgeois Like Me

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Bourgeois Like Me: Architecture, Literature, and the Making of the Middle Class in Post- War London A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Elizabeth Marly Floyd Committee in charge: Professor Maurizia Boscagli, Chair Professor Enda Duffy Professor Glyn Salton-Cox June 2019 The dissertation of Elizabeth Floyd is approved. _____________________________________________ Enda Duffy _____________________________________________ Glyn Salton-Cox _____________________________________________ Maurizia Boscagli, Committee Chair June 2019 Bourgeois Like Me: Architecture, Literature, and the Making of the Middle Class in Post- War Britain Copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Floyd iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the incredible and unwavering support I have received from my colleagues, friends, and family during my time at UC Santa Barbara. First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their guidance and seeing this project through its many stages. My ever-engaging chair, Maurizia Boscagli, has been a constant source of intellectual inspiration. She has encouraged me to be a true interdisciplinary scholar and her rigor and high intellectual standards have served as an incredible example. I cannot thank her enough for seeing potential in my work, challenging my perspective, and making me a better scholar. Without her support and guidance, I could not have embarked on this project, let alone finish it. She has been an incredible mentor in teaching and advising, and I hope to one day follow her example and inspire as many students as she does with her engaging, thoughtful, and rigorous seminars. -

Project Gutenberg's a Popular History of Ireland V2, by Thomas D'arcy Mcgee #2 in Our Series by Thomas D'arcy Mcgee

Project Gutenberg's A Popular History of Ireland V2, by Thomas D'Arcy McGee #2 in our series by Thomas D'Arcy McGee Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: A Popular History of Ireland V2 From the earliest period to the emancipation of the Catholics Author: Thomas D'Arcy McGee Release Date: October, 2004 [EBook #6633] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on January 6, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A POPULAR HISTORY OF IRELAND *** This etext was produced by Gardner Buchanan with help from Charles Aldarondo and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. A Popular History of Ireland: from the Earliest Period to the Emancipation of the Catholics by Thomas D'Arcy McGee In Two Volumes Volume II CONTENTS--VOL. -

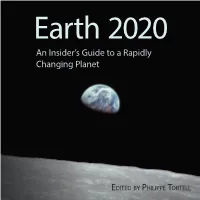

Earth 2020 an Insider’S Guide to a Rapidly Changing Planet

Earth 2020 An Insider’s Guide to a Rapidly Changing Planet EDITED BY PHILIPPE TORTELL P HILIPPE Earth 2020 Fi� y years has passed since the fi rst Earth Day, on April 22nd, 1970. This accessible, incisive and � mely collec� on of essays brings together a diverse set of expert voices to examine how the Earth’s environment has changed over these past fi � y years, and to An Insider’s Guide to a Rapidly consider what lies in store for our planet over the coming fi � y years. T ORTELL Earth 2020: An Insider’s Guide to a Rapidly Changing Planet responds to a public Changing Planet increasingly concerned about the deteriora� on of Earth’s natural systems, off ering readers a wealth of perspec� ves on our shared ecological past, and on the future trajectory of planet Earth. ( ED Wri� en by world-leading thinkers on the front-lines of global change research and .) policy, this mul� -disciplinary collec� on maintains a dual focus: some essays inves� gate specifi c facets of the physical Earth system, while others explore the social, legal and poli� cal dimensions shaping the human environmental footprint. In doing so, the essays collec� vely highlight the urgent need for collabora� on and diverse exper� se in addressing one of the most signifi cant environmental challenges facing us today. Earth 2020 is essen� al reading for everyone seeking a deeper understanding of the E past, present and future of our planet, and the role that humanity plays within this ARTH trajectory. As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the 2020 publisher’s website. -

Ship Shape As We Embark Upon a Project to Replace THV Patricia, We Take a Look at the Project Set-Up, Fact-Finding Missions and Progress So Far AUTUMN 2019 | ISSUE 31

The Trinity House journal // Autumn 2019 // Issue 31 Ship shape As we embark upon a project to replace THV Patricia, we take a look at the project set-up, fact-finding missions and progress so far AUTUMN 2019 | ISSUE 31 9 10 1 Welcome from Deputy Master, Captain Ian McNaught 13 2-4 Six-month review 5 News in brief 6 Coming events 7-8 Appointments/obituaries 9 27 Staff profile 10-12 THV Patricia replacement 13-14 Royal Sovereign decommissioning 15 Lundy North modernisation 16-17 Portland Bill upgrade 18 38 Swansea Buoy Yard lift 19-21 World Marine AtoN Day 22-24 Investments on the way IALA and the inception of an IGO Welcome to another edition of Flash; our staff have been hard at work driving forward 25 a number of projects with a great deal of progress to show for it. Many thanks are due IALA AtoN Manager course to everyone who contributed news and features to the issue, as always. Multi-skilled project teams have been working on two significant projects: one to 26-31 procure a vessel to replace the 1982-built THV Patricia, and another to manage the Charity update safe removal of the now-deteriorating Royal Sovereign Lighthouse. Elsewhere it was great to see the twin successes of Maritime Safety Week and 32-35 World Marine Aids to Navigation Day—both on 1 July—as our maritime partners at Partner profile: UK the Department for Transport and IALA further commit themselves to raising the Hydrographic Office profile of the national and global maritime sector. -

The Story of Our Lighthouses and Lightships

E-STORy-OF-OUR HTHOUSES'i AMLIGHTSHIPS BY. W DAMS BH THE STORY OF OUR LIGHTHOUSES LIGHTSHIPS Descriptive and Historical W. II. DAVENPORT ADAMS THOMAS NELSON AND SONS London, Edinburgh, and Nnv York I/K Contents. I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY, ... ... ... ... 9 II. LIGHTHOUSE ADMINISTRATION, ... ... ... ... 31 III. GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OP LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 39 IV. THE ILLUMINATING APPARATUS OF LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 46 V. LIGHTHOUSES OF ENGLAND AND SCOTLAND DESCRIBED, ... 73 VI. LIGHTHOUSES OF IRELAND DESCRIBED, ... ... ... 255 VII. SOME FRENCH LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... ... ... 288 VIII. LIGHTHOUSES OF THE UNITED STATES, ... ... ... 309 IX. LIGHTHOUSES IN OUR COLONIES AND DEPENDENCIES, ... 319 X. FLOATING LIGHTS, OR LIGHTSHIPS, ... ... ... 339 XI. LANDMARKS, BEACONS, BUOYS, AND FOG-SIGNALS, ... 355 XII. LIFE IN THE LIGHTHOUSE, ... ... ... 374 LIGHTHOUSES. CHAPTER I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY. T)OPULARLY, the lighthouse seems to be looked A upon as a modern invention, and if we con- sider it in its present form, completeness, and efficiency, we shall be justified in limiting its history to the last centuries but as soon as men to down two ; began go to the sea in ships, they must also have begun to ex- perience the need of beacons to guide them into secure channels, and warn them from hidden dangers, and the pressure of this need would be stronger in the night even than in the day. So soon as a want is man's invention hastens to it and strongly felt, supply ; we may be sure, therefore, that in the very earliest ages of civilization lights of some kind or other were introduced for the benefit of the mariner. It may very well be that these, at first, would be nothing more than fires kindled on wave-washed promontories, 10 LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY.