Burrows T., 2018 There Never Was Such A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Phillipps Och Mellanrummet Kärrholm, Mattias

Thomas Phillipps och mellanrummet Kärrholm, Mattias Published in: Oei 2011 Document Version: Förlagets slutgiltiga version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kärrholm, M. (2011). Thomas Phillipps och mellanrummet. Oei, (53-54), 1237-1246. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 1 Thomas Phillipps och mellanrummet Av Mattias Kärrholm (OBS! Texten är en tidigare version av artikeln, Kärrholm, M (2011) ”Thomas Phillips och mellanrummet”, OEI 53-54, s. 1237-1246). Det har aldrig funnits en större centralgestalt för boksamlandet än sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872). Thomas Phillipps utgick från den numera närmast legendariska sentensen ”I wish to have one copy of every book in the world”, och gjorde sedan allt för att försöka realisera denna önskan. -

The Sonnets and Shorter Poems

AN ANALYSIS OF A NOTEBOOK OF JAMES ORCHARD HALLIWELL-PHILLIPPS THE SONNETS AND SHORTER POEMS by ELIZABETH PATRICIA PRACY A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts of The University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY The Shakespeare Institute Faculty of Arts The University of Birmingham March 1999 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. O t:O SYNOPSIS The thesis starts with an Introduction which explains that the subject of the work is an analysis of the Notebook of J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps dealing with the Sonnets and shorter poems of Shakespeare owned by the Shakespeare Centre Library, Stratford-upon- Avon. This is followed by an explanation of the material and methods used to examine the pages of the Notebook and a brief account of Halliwell-Phillipps and his collections as well as a description of his work on the life and background of Shakespeare. Each page of the Notebook is then dealt with in order and outlined, together with a photocopy of Halliwell-Phillipps1 entry. Entries are identified where possible, with an explanation and description of the work referred to. -

1 Ossified Collections Embody the Manifold Reasons Motivating Private Collectors

Ossified Collections: The Past Encapsulated in British Institutions Today Karen Attar Chapter published in: Collecting the Past: British Collectors and their Collections from the 18th to the 20th Centuries, ed. by Toby Burrows and Cynthia Johnston (London: Routledge, 2019), pp. 113-38 ‘Floreat bibliomania’, entitled that great collector A.N.L. Munby an article published in the New Statesman on 21 June 1952.1 Munby’s main interest was in sale catalogues as records of books assembled and then dispersed.2 This essay provides an overview of a more philanthropic and stable end to collecting: collections of primarily printed books in the British Isles that have stayed together and now enrich institutions, causing broader swathes of scholars and librarians to echo Munby’s prayer. Whilst some outstanding collectors and bibliophiles are highlighted in the standard literature of collecting and other more modest ones are noted in magisterial histories of institutions, feature in dedicated articles, or are commemorated in published catalogues of their collections, these remain the minority.3 This overview is based more widely on some of what has been described as ‘the rest of the iceberg’, through a survey of 873 repositories in the British Isles: national, academic, school, public, subscription and professional libraries, or in trusts, cathedrals, churches, monasteries, London clubs, archives, museums, schools, companies, and stately homes.4 Discussing popular collecting subjects and trends in collecting, it concentrates on ‘collections’ as groups of books with some unifying element, most of which originated with an individual before entering corporate ownership, whilst retaining at least some semblance of their former identity. -

Monday 03 July 2017: 09.00-10.30

MONDAY 03 JULY 2017: 09.00-10.30 Session: 1 Great Hall KEYNOTE LECTURE 2017: THE MEDITERRANEAN OTHER AND THE OTHER MEDITERRANEAN: PERSPECTIVE OF ALTERITY IN THE MIDDLE AGES (Language: English) Nikolas P. Jaspert, Historisches Seminar, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg DRAWING BOUNDARIES: INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION IN MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC SOCIETIES (Language: English) Eduardo Manzano Moreno, Instituto de Historia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Madrid Introduction: Hans-Werner Goetz, Historisches Seminar, Universität Hamburg Details: ‘The Mediterranean Other and the Other Mediterranean: Perspective of Alterity in the Middle Ages’: For many decades, the medieval Mediterranean has repeatedly been put to use in order to address, understand, or explain current issues. Lately, it tends to be seen either as an epitome of transcultural entanglements or - quite on the contrary - as an area of endemic religious conflict. In this paper, I would like to reflect on such readings of the Mediterranean and relate them to several approaches within a dynamic field of historical research referred to as ‘xenology’. I will therefore discuss different modalities of constructing self and otherness in the central and western Mediterranean during the High and Late Middle Ages. The multiple forms of interaction between politically dominant and subaltern religious communities or the conceptual challenges posed by trans-Mediterranean mobility are but two of the vibrant arenas in which alterity was necessarily both negotiated and formed during the medieval millennium. Otherness is however not reduced to the sphere of social and thus human relations. I will therefore also reflect on medieval societies’ dealings with the Mediterranean Sea as a physical and oftentimes alien space. -

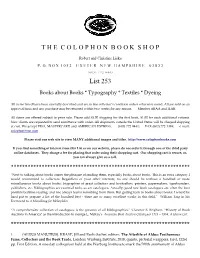

Page 143/144 and Black Page Following Are Detached but Laid In, Final Blank Page Has Handwritten Notes in Ink on Dyeing

T H E C O L O P H O N B O O K S H O P Robert and Christine Liska P. O. B O X 1 0 5 2 E X E T E R N E W H A M P S H I R E 0 3 8 3 3 ( 6 0 3 ) 7 7 2 8 4 4 3 List 253 Books about Books * Typography * Textiles * Dyeing All items listed have been carefully described and are in fine collector’s condition unless otherwise noted. All are sold on an approval basis and any purchase may be returned within two weeks for any reason. Member ABAA and ILAB. All items are offered subject to prior sale. Please add $5.00 shipping for the first book, $1.00 for each additional volume. New clients are requested to send remittance with order. All shipments outside the United States will be charged shipping at cost. We accept VISA, MASTERCARD and AMERICAN EXPRESS. (603) 772-8443; FAX (603) 772-3384; e-mail: [email protected] Please visit our web site to view MANY additional images and titles. http://www.colophonbooks.com If you find something of interest from this List or on our website, please do not order it through one of the third party online databases. They charge a fee for placing that order using their shopping cart. Our shopping cart is secure, or, you can always give us a call. ☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼ “Next to talking about books comes the pleasure of reading them, especially books about books. This is an extra category I would recommend to collectors. -

Anuscripts on My Mind

anuscripts on my mind News from the No. 28 September 2019 ❧ Editor’s Remarks ❧ Exhibitions ❧ Queries and Comments ❧ Conferences and Symposia ❧ New Publications, etc. ❧ Editor’s Remarks ear colleagues and manuscript lovers, we are now close to starting a new season. After a not-so- Dunbearable summer, things seem to be cooling off a bit, and I'm looking forward to walking around with a jacket on instead of tank tops (though I've kept a jacket and wooly sweaters in my office all sum- mer to counteract the freezing A/C). I have a couple of announcements to make as I put the finishing touches to this issue of Manuscripts on My Mind. The first is to report that this year's 46th Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies— held on June 17 and 18 and embedded in the annual Symposium on Medieval and Renaissance Studies organized by the Center for Medieval Studies at Saint Louis University—was uniformly brilliant: papers were especially well crafted, beautifully delivered, presented new material and ideas, and gave us all a lot to think about. Francesca Manzari's plenary lecture assessed the relatively unexplored topic of four- teenth-century Italian Books of Hours, connecting them with similar devotional instruments and texts and amplifying our knowledge about pious activities of the time. My great thanks to all who made it such a memorable occasion. The next news is more difficult to put into words. I deeply regret having to tell you that next year's 47th Saint Louis Conference on Manuscript Studies, to be held June 15-17, 2020, will be the last I organize and officiate. -

Gallery Copy

w GALLERY COPY This exhibition is presented in collaboration by the British Museum, the Museum of New Mexico Foundation and the New Mexico Museum of Art, a division of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs. w JANUARY 25 – APRIL 19, 2020 Unless otherwise stated all images are © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights are reserved for the written content of this booklet by © The Trustees of the British Museum. Giovanni Battista Pasqualini, The Incredulity of St. Thomas, after Guercino, 1621. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum. 1 St. Louis He was King Louis IX of France, born in 1214 and dying in 1270. Louis was a follower of St. Francis of Assisi and known for his piety and devotion to the poor. He invited hundreds of poor subjects to his palace every day where he served them and attended to their needs. He personally led two Crusades to the Holy Land. He founded the beautiful Church of St. Chapelle in Paris where he placed the supposed Crown of Thorns. St. Mary Magdalene Mary is identified as a Jewish woman who was a devoted follower of Christ, witnessing his crucifixion, burial, and resurrection. She was reported to be a repentant prostitute who revered Christ. In art, she is shown as washing Christ’s feet with her tears and drying them with her hair. In return, Christ forgives her and absolves her of all her sins. According to the Gnostic Gospel of Mary, after Christ’s death she acted as a spiritual guide spreading his teachings. This exhibition presents a selection of Italian prints and drawings from the British Museum in London. -

Beyond Macbeth Exhibition Catalogue

BEYOND MACBETH: SHAKESPEARE COLLECTIONS IN SCOTLAND An exhibition held at National Library of Scotland from 9 December 2011 until 29 April 2012, featuring items from the collections of NLS and the University of Edinburgh, and supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. The National Library and the University wish to thank the following for their assistance: The Abbotsford Trust, Edinburgh City Libraries, London Metropolitan Archives, Lauren Pope, Ross Crombie and Mark Scott, National Galleries of Scotland, National Portrait Gallery, London, Rijksmuseum, The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Victoria Johnston, Daisy Badger, David K Barnes, The estate of Robert Lyon. The exhibition was curated by James Loxley and Helen Vincent, and designed by Studio MB. Edinburgh, 2012 Copyright the National Library of Scotland and the University of Edinburgh If you require this document in an alternative format e.g. large print, please email [email protected] University of Edinburgh is a charitable body, registered in Scotland, with registration number SC005336. Designed by The Multimedia Team, Information Services, The University of Edinburgh www.ed.ac.uk/is/graphic-design Beyond Macbeth: Shakespeare Collections in Scotland Introduction William Shakespeare is the best known writer in the world. He is generally held not only to be the greatest playwright but also the greatest writer in the English language. His plays have rarely been out of the repertory since their earliest production in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and have been available to readers in an astonishing range of printed editions for most of that time too. His characters and words have long been a part of common consciousness: phrases such as ‘star-crossed lovers’ and the ‘mind’s eye’ have become part of the fabric of the English language, and figures such as Hamlet have been taken to represent aspects of a general or universal human condition. -

Introduction to Bibliography

INTRODUCTION TO BIBLIOGRAPHY Seminar Syllabus G. THOMAS TANSELLE ! Syllabus for English/Comparative Literature G4010 Columbia University ! Charlottesville B O O K A R T S P R E S S University of Virginia 2002 This page is from a document available in full at http://www.rarebookschool.org/tanselle/ Nineteenth revision, 2002 Copyright © 2002 by G. Thomas Tanselle Copies of this syllabus are available for $25 postpaid from: Book Arts Press Box 400103, University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA 22904-4103 Telephone 434-924-8851 C Fax 434-924-8824 Email <[email protected]> C Website <www.rarebookschool.org> Copies of a companion booklet, Introduction to Scholarly Editing: Seminar Syllabus, are available for $20 from the same address. This page is from a document available in full at http://www.rarebookschool.org/tanselle/ CONTENTS Preface • 10 Part 1. The Scope and History of Bibliography and Allied Fields • 13-100 Part 2. Bibliographical Reference Works and Journals • 101-25 Part 3. Printing and Publishing History • 127-66 Part 4. Descriptive Bibliography • 167-80 Part 5. Paper • 181-93 Part 6. Typography, Ink, and Book Design • 195-224 Part 7. Illustration • 225-36 Part 8. Binding • 237-53 Part 9. Analytical Bibliography • 255-365 Subject Index • 367-70 A more detailed outline of the contents is provided on the next six pages. This page is from a document available in full at http://www.rarebookschool.org/tanselle/ 4 Tanselle: Introduction to Bibliography (2002) OUTLINE OF CONTENTS 1. The Scope and History of Bibliography and Allied Fields A. Selected Basic Readings (pages 13-14) B. -

A Shakespearean Constellation: J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps and Friends

A Shakespearean Constellation: J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps and Friends Marvin Spevack Marvin Spevack A Shakespearean Constellation: J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps and Friends Wissenschaftliche Schriften der WWU Münster Reihe XII Band 5 Marvin Spevack A Shakespearean Constellation: J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps and Friends Wissenschaftliche Schriften der WWU Münster herausgegeben von der Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Münster http://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de Marvin Spevack held a chair of English Philology at the University of Münster. After producing essential works on Shakespeare Ý concordances, editions, and a thesaurus – he turned to literary figures of the nineteenth century with studies of James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps, Isaac D'Israeli, Sidney Lee, Francis Turner Palgrave, and now a constellation of Victorian Shakespeare scholars. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Dieses Buch steht gleichzeitig in einer elektronischen Version über den Publikations- und Archivierungsserver der WWU Münster zur Verfügung. http://www.ulb.uni-muenster.de/wissenschaftliche-schriften Marvin Spevack „A Shakespearean Constellation: J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps and Friends“ Wissenschaftliche Schriften der WWU Münster, Reihe XII, Band 5 © 2013 der vorliegenden Ausgabe: Die Reihe „Wissenschaftliche Schriften der WWU Münster“ erscheint im Verlagshaus Monsenstein und Vannerdat OHG Münster www.mv-wissenschaft.com ISBN 978-3-8405-0078-7 (Druckausgabe) URN urn:nbn:de:hbz:6-28309453353 (elektronische Version) direkt zur Online-Version: © 2013 Marvin Spevack Alle Rechte vorbehalten Satz: Marvin Spevack Titelbild: Carl Spitzweg, „Der Sterndeuter“ (ca. 1860-1865) Quelle: http://www.zeno.org Umschlag: MV-Verlag Druck und Bindung: MV-Verlag To MM and MCD CONTENTS PREFACE ix PART ONE:EDITORS 1 1. -

Spring 2004) file:///Users/Sduncan/Documents/ARLIS-TXMX

ARLIS/Texas-Mexico: The Medium: v.30, no.1 (spring 2004) file:///Users/sduncan/Documents/ARLIS-TXMX/www.arlis-txm... D I V I S I O N N E W S Academic Libraries v. 30, no. 1 (spring 2004) | issues Our very own Laura Schwartz, regional representative, has been named Head of the Fine Arts PRESIDENT'S COLUMN Library at the University of Texas. Dear Colleagues, When The Medium requested biographical material she sent the Although it is early summer as I draft this message, the recent spring following: witnessed a tremendous amount of activity that I am pleased to share with you. "I own three canine children, Hank, Winnie and Scruffy. I would never Soon after the Chapter meeting last November in New Orleans, then-Vice have gotten to where I am without President/President-Elect Mary Leonard informed the Executive them." (Laura, with names like Committee that she would be unable to fulfill her term as president for that, we can only imagine their 2004. According to our Chapter bylaws, this meant that I, as the vice lineage and place of origin.) president/president-elect for 2004, would fulfill her term for that year, in addition to my own for 2005. The task then fell to me to appoint a vice On a less personal note, she president who could not be in the presidential line of succession as an included the following press unelected officer. I am very pleased that Gwen Dixie has volunteered to release: serve one year as vice president. As you know, her chief responsibility is Laura Schwartz named Fine Arts to produce the Medium and I believe this issue will show that Gwen is Library Head well suited for the task.