Screenplay Format & Style Standards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GCWC WAG Creative Writing

GASTON COLLEGE Creative Writing Writing Center I. GENERAL PURPOSE/AUDIENCE Creative writing may take many forms, such as fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry, playwriting, and screenwriting. Creative writers can turn almost any situation into possible writing material. Creative writers have a lot of freedom to work with and can experiment with form in their work, but they should also be aware of common tropes and forms within their chosen style. For instance, short story writers should be aware of what represents common structures within that genre in published fiction and steer away from using the structures of TV shows or movies. Audiences may include any reader of the genre that the author chooses to use; therefore, authors should address potential audiences for their writing outside the classroom. What’s more, students should address a national audience of interested readers—not just familiar readers who will know about a particular location or situation (for example, college life). II. TYPES OF WRITING • Fiction (novels and short stories) • Creative non-fiction • Poetry • Plays • Screenplays Assignments will vary from instructor to instructor and class to class, but students in all Creative Writing classes are assigned writing exercises and will also provide peer critiques of their classmates’ work. In a university setting, instructors expect prose to be in the realistic, literary vein unless otherwise specified. III. TYPES OF EVIDENCE • Subjective: personal accounts and storytelling; invention • Objective: historical data, historical and cultural accuracy: Work set in any period of the past (or present) should reflect the facts, events, details, and culture of its time and place. -

The Ontology and Literary Status of the Screenplay:The Case of »Scriptfic«

DOI 10.1515/jlt-2013-0006 JLT 2013; 7(1–2): 135–153 Ted Nannicelli The Ontology and Literary Status of the Screenplay:The Case of »Scriptfic« Abstract: Are screenplays – or at least some screenplays – works of literature? Until relatively recently, very few theorists had addressed this question. Thanks to recent work by scholars such as Ian W. Macdonald, Steven Maras, and Steven Price, theorizing the nature of the screenplay is back on the agenda after years of neglect (albeit with a few important exceptions) by film studies and literary studies (Macdonald 2004; Maras 2009; Price 2010). What has emerged from this work, however, is a general acceptance that the screenplay is ontologically peculiar and, as a result, a divergence of opinion about whether or not it is the kind of thing that can be literature. Specifically, recent discussion about the nature of the screenplay has tended to emphasize its putative lack of ontological autonomy from the film, its supposed inherent incompleteness, or both (Carroll 2008, 68–69; Maras 2009, 48; Price 2010, 38–42). Moreover, these sorts of claims about the screenplay’s ontology – its essential nature – are often hitched to broader arguments. According to one such argument, a screenplay’s supposed ontological tie to the production of a film is said to vitiate the possibility of it being a work of literature in its own right (Carroll 2008, 68–69; Maras 2009, 48). According to another, the screenplay’s tenuous literary status is putatively explained by the idea that it is perpetually unfinished, akin to a Barthesian »writerly text« (Price 2010, 41). -

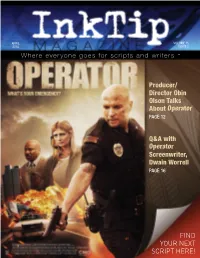

Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12

APRIL VOLUME 15 2015 ISSUE 2 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers ™ Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12 Q&A with Operator Screenwriter, Dwain Worrell PAGE 16 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! Where everyone goes for writers and scripts™ IT’S FAST AND EASY TO FIND THE SCRIPT OR WRITER YOU NEED. WWW.INKTIP.COM A FREE SERVICE FOR ENTERTAINMENT PROFESSIONALS. Peruse this magazine, find the scripts/books you like, and go to www.InkTip.com to search by title or author for access to synopses, resumes and scripts! l For more information, go to: www.InkTip.com. l To register for access, go to: www.InkTip.com and click Joining InkTip for Entertainment Pros l Subscribe to our free newsletter at http://www.inktip.com/ep_newsletters.php Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they can place their scripts on our site. Table of Contents Recent Successes 3, 9, 11 Feature Scripts – Grouped by Genre 7 Industry Endorsements 3 Feature Article: Operator 12 Contest/Festival Winners 4 Q&A: Operator Screenwriter Dwain Worrell 16 Writers Represented by Agents/Managers 4 Get Your Movie on the Cover of InkTip Magazine 18 Teleplays 5 3 Welcome to InkTip! The InkTip Magazine is owned and distributed by InkTip. Recent Successes In this magazine, we provide you with an extensive selection of loglines from all genres for scripts available now on InkTip. Entertainment professionals from Hollywood and all over the Bethany Joy Lenz Options “One of These Days” world come to InkTip because it is a fast and easy way to find Bethany Joy Lenz found “One of These Days” on InkTip, great scripts and talented writers. -

Why Does the Screenwriter Cross the Road…By Joe Gilford 1

WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD…BY JOE GILFORD 1 WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD? …and other screenwriting secrets. by Joe Gilford TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION (included on this web page) 1. FILM IS NOT A VISUAL MEDIUM 2. SCREENPLAYS ARE NOT WRITTEN—THEY’RE BUILT 3. SO THERE’S THIS PERSON… 4. SUSTAINABLE SCREENWRITING 5. WHAT’S THE WORST THAT CAN HAPPEN?—THAT’S WHAT HAPPENS! 6. IF YOU DON’T BELIEVE THIS STORY—WHO WILL?? 7. TOOLBAG: THE TRICKS, GAGS & GADGETS OF THE TRADE 8. OK, GO WRITE YOUR SCRIPT 9. NOW WHAT? INTRODUCTION Let’s admit it: writing a good screenplay isn’t easy. Any seasoned professional, including me, can tell you that. You really want it to go well. You really want to do a good job. You want those involved — including yourself — to be very pleased. You really want it to be satisfying for all parties, in this case that means your characters and your audience. WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD…BY JOE GILFORD 2 I believe great care is always taken in writing the best screenplays. The story needs to be psychically and spiritually nutritious. This isn’t a one-night stand. This is something that needs to be meaningful, maybe even last a lifetime, which is difficult even under the best circumstances. Believe it or not, in the end, it needs to make sense in some way. Even if you don’t see yourself as some kind of “artist,” you can’t avoid it. You’re going to be writing this script using your whole psyche. -

How to Format Your Script

How to format your Script Many screenwriting books specify formats that may not still be in general use today, or which contain directions that may be unnecessary. The following format tips are accurate and will result in your screenplay being formatted in the correct manner. These tips apply only to a spec script. A production script contains editing and camera directions (and scene numbers) all of which are only added after a script goes into production, and should not be included in a spec script, the purpose of which is only to present the basic story. How the story is interpreted on the screen is up to the director, not the writer. LENGTH: Ideally, a screenplay for a regular feature film for theatrical release or for television should be between 100 and 120 pages. DO NOT list a cast of characters before the first page of the script. And, DO NOT number the scenes. THERE ARE ONLY THREE ELEMENTS NECESSARY IN A SPEC SCRIPT: · THE SCENE HEADING (INTERIOR OR EXTERIOR, LOCATION, TIME) · THE VISUAL EXPOSITION (Only what you would see if you were watching the screen) · THE DIALOGUE (1) The Scene Heading sets the stage for the action and dialogue to follow. It tells us where the story is taking place, and the time of day. There are only two locations where this can happen, inside (INT) or outside (EXT). The specific location and geographic placement should be included as well. The scene heading is positioned on your first indent, one-and-a-half inches in from the left hand side of the page. -

Introduction Screenwriting Off the Page

Introduction Screenwriting off the Page The product of the dream factory is not one of the same nature as are the material objects turned out on most assembly lines. For them, uniformity is essential; for the motion picture, originality is important. The conflict between the two qualities is a major problem in Hollywood. hortense powdermaker1 A screenplay writer, screenwriter for short, or scriptwriter or scenarist is a writer who practices the craft of screenwriting, writing screenplays on which mass media such as films, television programs, comics or video games are based. Wikipedia In the documentary Dreams on Spec (2007), filmmaker Daniel J. Snyder tests studio executive Jack Warner’s famous line: “Writers are just sch- mucks with Underwoods.” Snyder seeks to explain, for example, why a writer would take the time to craft an original “spec” script without a mon- etary advance and with only the dimmest of possibilities that it will be bought by a studio or producer. Extending anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker’s 1950s framing of Hollywood in the era of Jack Warner and other classic Hollywood moguls as a “dream factory,” Dreams on Spec pro- files the creative and economic nightmares experienced by contemporary screenwriters hoping to clock in on Hollywood’s assembly line of creative uniformity. There is something to learn about the craft and profession of screenwrit- ing from all the characters in this documentary. One of the interviewees, Dennis Palumbo (My Favorite Year, 1982), addresses the downside of the struggling screenwriter’s life with a healthy dose of pragmatism: “A writ- er’s life and a writer’s struggle can be really hard on relationships, very hard for your mate to understand. -

Summer 2019 Vol.21, No.3 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SUMMER 2019 VOL.21, NO.3 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA A Rock Star in the Writers’ Room: Bringing Jann Arden to the small screen Crafting Canadian Horror Stories — and why we’re so good at it Celebrating the 23rd annual WGC Screenwriting Awards Emily Andras How she turned PM40011669 Wynonna Earp into a fan phenomenon Congratulations to Emily Andras of SPACE’s Wynonna Earp, Sarah Dodd of CTV’s Cardinal, and all of the other 2019 WGC Screenwriting Award winners. Proud to support Canada’s creative community. CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 21 No. 3 Summer 2019 ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Publisher Maureen Parker Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Contents Director of Communications Lana Castleman Cover Editorial Advisory Board There’s #NoChill When it Comes Michael Amo to Emily Andras’s Wynonna Earp 6 Michael MacLennan How 2019’s WGC Showrunner Award winner Emily Susin Nielsen Andras and her room built a fan and social media Simon Racioppa phenomenon — and why they’re itching to get back in Rachel Langer the saddle for Wynonna’s fourth season. President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) By Li Robbins Councillors Michael Amo (Atlantic) Features Mark Ellis (Central) What Would Jann Do? 12 Marsha Greene (Central) That’s exactly the question co-creators Leah Gauthier Alex Levine (Central) and Jennica Harper asked when it came time to craft a Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) heightened (and hilarious) fictional version of Canadian Andrew Wreggitt (Western) icon Jann Arden’s life for the small screen. -

Rewriting Aristotle: the Uses and Misuses of the Poetics in the Teaching and Practice of Screenwriting

Rewriting Aristotle: the Uses and Misuses of the Poetics in the Teaching and Practice of Screenwriting Brian Dunnigan, Head of Screenwriting, London Film School October 2014 “ All human beings by nature desire knowledge.” Aristotle (Metaphysics) “ Tragedy is essentially an imitation not of persons but of action and of life.” Aristotle (Poetics) “The film language is the most elaborate, the most secret and the most invisible. A good script is a script that you don’t notice. It has vanished. Being a screenwriter is not the last step of a literary adventure but the first step of a film adventure…therefore a screenwriter must know everything about the techniques of how to make a film.” Jean-Claude Carrière I read with interest that amongst the early aims of the Screenwriting Research Network is that of “ interpreting documents intended to describe the screen idea” and a study of “ the interaction of those agents concerned with constructing the screenwork.” We are presumably referring here to the screenplay and the screenwriters and filmmakers working toward the creation of a film. The lively, anxious, imaginative humans who struggle to express themselves in conversation and debate, to shape a meaningful narrative for an audience. As an educator involved with curious and often confused humans trying to understand what it is they have to say about the world - I find that description of theoretical practice misses too much of what excites me about storytelling and cinema. This is partly language and partly to do with how as a writer and teacher one prefers to think about the process of filmmaking. -

Introduction 1 Mimesis and Film Languages

Notes Introduction 1. The English translation is that provided in the subtitles to the UK Region 2 DVD release of the film. 2. The rewarding of Christoph Waltz for his polyglot performance as Hans Landa at the 2010 Academy Awards recalls other Oscar- winning multilin- gual performances such as those by Robert de Niro in The Godfather Part II (Coppola, 1974) and Meryl Streep in Sophie’s Choice (Pakula, 1982). 3. T h is u nder st a nd i ng of f i l m go es bac k to t he era of si lent f i l m, to D.W. Gr i f f it h’s famous affirmation of film as the universal language. For a useful account of the semiotic understanding of film as language, see Monaco (2000: 152–227). 4. I speak here of film and not of television for the sake of convenience only. This is not to undervalue the relevance of these questions to television, and indeed vice versa. The large volume of studies in existence on the audiovisual translation of television texts attests to the applicability of these issues to television too. From a mimetic standpoint, television addresses many of the same issues of language representation. Although the bulk of the exempli- fication in this study will be drawn from the cinema, reference will also be made where applicable to television usage. 1 Mimesis and Film Languages 1. There are, of course, examples of ‘intralingual’ translation where films are post-synchronised with more easily comprehensible accents (e.g. Mad Max for the American market). -

A Genre Is a Conventional Response to a Rhetorical Situation That Occurs Fairly Often

What is a genre? A genre is a conventional response to a rhetorical situation that occurs fairly often. Conventional does not necessarily mean boring. Instead, it means a recognizable pattern for providing specific kinds of information for an identifiable audience demanded by circumstances that come up again and again. For example, new movies open almost every week. Movie makers pay for advertising to entice viewers to see their movies. Genres have a purpose. While consumers may learn about a movie from the ads, they know they are getting a sales pitch with that information, so they look for an outside source of information before they spend their money. Movie reviews provide viewers with enough information about the content and quality of a film to help them make a decision, without ruining it for them by giving away the ending. Movie reviews are the conventional response to the rhetorical situation of a new film opening. Genres have a pattern. The movie review is conventional because it follows certain conventions, or recognized and accepted ways of giving readers information. This is called a move pattern. Here are the moves associated with that genre: 1. Name of the movie, director, leading actors, Sometimes, the opening also includes the names of people and companies associated with the film if that information seems important to the reader: screenwriter, animators, special effects, or other important aspects of the film. This information is always included in the opening lines or at the top of the review. 2. Graphic design elements---usually, movie reviews include some kind of art or graphic taken from the film itself to call attention to the review and draw readers into it. -

Scriptwriting Theories & Practice

Storyboarding and Scriptwriting • AD210 • Spring 2011 • Gregory V. Eckler Storyboarding and Scriptwriting Scriptwriting Theories & Practice Theories on Scriptwriting Fundamentally, the screenplay is a unique literary form. It is like a musical score, in that it is intended to be interpreted on the basis of other artists’ performance, rather than serving as a “finished product” for the enjoyment of its audience. For this reason, a screenplay is written using technical jargon and tight, spare prose when describing stage directions. Unlike a novel or short story, a screenplay focuses on describing the literal, visual aspects of the story, rather than on the internal thoughts of its characters. In screenwriting, the aim is to evoke those thoughts and emotions through subtext, action, and symbolism. There are several main screenwriting theories which help writers approach the screenplay by systematizing the structure, goals and techniques of writing a script. The most common kinds of theories are structural. Screenwriter William Goldman is widely quoted as saying “Screenplays are structure”. Three act structure Most screenplays have a three act structure, following an organization that dates back to Aristotle’s Poetics. The three acts are setup (of the location and characters), confrontation (with an obstacle), and resolution (culminating in a climax and a dénouement). In a two-hour film, the first and third acts both typically last around 30 minutes, with the middle act lasting roughly an hour. In Writing Drama, French writer and director Yves Lavandier shows a slightly different approach. As most theorists, he maintains that every human action, whether fictitious or real, contains three logical parts: before the action, during the action, and after the action. -

New Histories of Hollywood Roundtable Moderated by Luci Marzola

Chris Cagle, Emily Carman, Mark Garrett Cooper, Kate Fortmueller, Eric Hoyt, Denise McKenna, Ross Melnick, Shelley Stamp New Histories of Hollywood Roundtable Moderated by Luci Marzola As part of this issue on “The System Beyond the Studios,” I sought not only to give scholars an opportunity to publish work that looks at specific cases reassessing the history of Hollywood, but I also wanted to look more broadly at the state of the field of American film history. As such, I assembled a roundtable of scholars who have been studying Hollywood through myriad lenses for most of their careers. I wanted to know, from their perspective, what were the current and future threads to be taken up in the study of this central topic in cinema and media studies. The roundtable discussion focuses on innovative methods, sources, and approaches that give us new insights into the study of Hollywood. Chris Cagle, Emily Carman, Mark Garrett Cooper, Kate Fortmueller, Eric Hoyt, Denise McKenna, Ross Melnick, and Shelley Stamp all participated while I moderated the conversation. It was conducted via email and Google docs in the fall of 2017. Each participant began by writing a brief response to a broad question on one topic – research, methodology, pedagogy, or the meaning of ‘Hollywood.’ These responses were then culled together and given follow up questions which were all placed in a Google drive folder. Over the course of two months, the participants added responses, provocations, and questions on each of the threads, while I added follow up questions to guide the discussion. When seen as a whole, this roundtable creates a snapshot of where the field of Hollywood history is at this moment.