Copyright by Willie Yvonne Johnson 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2003 Tattersalls October Nj Yearling Sale

2003 October Yearling Sale Conducted by The Lexington Trots Breeders Association, LLC at The Meadowlands in East Rutherford, NJ starting at 12:00 Noon Monday, October 13 Yearlings 1 - 195 Since 1892 Tattersalls P.O. Box 420, Lexington, KY 40588 (859) 422-7253 • (859) 422-SALE Fax (859) 422-7254 or (914) 773-7777 • Fax (914) 773-1633 Website - www.tattersallsredmile.com e-mail - [email protected] Sale Day Only - 201-935-8500 1 2 The Lexington Trot Breeders Association, LLC d/b/a Tattersalls Sales Company Directors Frank Antonacci Mrs. Paul Nigito George Segal Joe Thomson Tattersalls Sales: Administration Staff Geoffrey Stein ....................................................... General Manager David Reid ...................................................... Director of Operations Shannon Cobb .......................................................................... CFO Joan Paynter ...................................................... Sales Administrator Lillie Brown .................................................. Administrative Assistant Doug Ferris.................................................. Administrative Assistant Sales Consultants Howard Beissinger ..................................... Senior Sales Consultant Dr. Peter Boyce .......................................................Sales Consultant Auctioneers Chris Caldwell and Associates Pedigree Research Philip D. Sporn & Tattersalls Pedigree Research Dept. 3 Change of Address Form Please use this form to send us a change of address so you’ll never miss your Tattersalls -

Canadian B-Movie on Eastern Tour

1 The Grapevine Mar 18 - Apr 1, 2010 . issue N o 3.21 Banner by Zachary, Nolan and Jillian Hatt; ages 10, 7, 5 Mar 18 - Apr 1, 2010 COMMUNITY AWARENESS INVOLVEMENT Our Readership is now approx. 2700! 4………TWO-WEEK TWEETS Best of Kings, 2010 - pg 2 KNOW THIS 5………EAT TO THE BEAT, PERSON? Keep your Marbles! - pg 9 6 & 7 …EVENTS CALENDAR Find out on 8………THE FREE CLASSIFIEDS page 11 Little Shop of Horrors - pg 9 10……..STARDROP Canadian B-Movie on Eastern Tour he directors of a B culture secret; and a group of Tart movie, Heidi and friends trying to have a get Colin Burrowes, are taking away who find themselves their movie Gopher Wood to hopelessly out of their ele- eastern Canada this week. Go- ment. The screening time pher Wood is an independent of the movie is approxi- Shy Sisters Canadian film shot in Listowel, mately 75 minutes. Not DIANE AND DENISE have been Ontario by Duramater Produc- recommended for children. with us since January of last year. tions. Due to shyness they are regularly Gopher Wood is overlooked. Do you think you This is the culmination propelled by an excellent could consider adopting one of of two years of hard work writ- cast which includes Miss these sisters? Kitten season is ing, casting, preparing props, Canada 2008 Shannon around the corner and we don’t shooting, and postproduction. Smadella & Peter Bavis want to see them passed by again. The directors are looking for (“Canada’s answer to Please adopt the true meaning of audience feedback during these Philip Seymour Hoffman” rescue. -

Billboard Magazine

HOT R&B/HIP-HOP SONGS™ TOP R&B/HIP-HOP ALBUMS™ 2 WKS. LAST THIS TITLE CERTIFICATION Artist PEAK WKS. ON LAST THIS ARTIST CERTIFICATION Title WKS. ON AGO WEEK WEEK PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL POS. CHART WEEK WEEK IMPRINT/DISTRIBUTING LABEL CHART HOT #1 #1 BODAK YELLOW (MONEY MOVES) 0 Cardi B SHOT 1 MACKLEMORE GEMINI 1 111 1 5 WKS 113 DEBUT 1 WK BENDO JEFF KRAVITZ/FILMMAGIC J WHITE,SHAFTIZM (J WHITE,SHAFTIZM,J.THORPE,WASHPOPPIN) THE KSR GROUP/ATLANTIC LIL UZI VERT ROCKSTAR 1 2 Luv Is Rage 2 5 -22 2 AG Post Malone Featuring 21 Savage 2 2 GENERATION NOW/ATLANTIC/AG L.BELL,TANK GOD (A.POST,L.BELL,O.AWOSHILEY,S.A.JOSEPH) REPUBLIC 1-800-273-8255 50 3 GG KEVIN GATES By Any Means 2 2 233 0 Logic Featuring Alessia Cara & Khalid 2 22 BREAD WINNERS’ ASSOCIATION/ATLANTIC/AG LOGIC,6IX (SIR R.B.HALL II,A.IVATURY,A.CARACCIOLO,K.ROBINSON,A.TAGGART) VISIONARY/DEF JAM NEW 4 JHENE AIKO Trip 1 444 UNFORGETTABLE 3 French Montana Featuring Swae Lee 225 ARTCLUB/ARTIUM/DEF JAM MIKE WILL MADE-IT,C.P. DUBB,JAEGEN,M.R.SUTPHIN (K.KHARBOUCH,K.U.BROWN,M.L.WILLIAMS . .) EAR DRUMNER/COKE BOYS/BAD BOY/INTERSCOPE/EPIC 5 5 PS POST MALONE ¡ Stoney 42 RAKE IT UP REPUBLIC Gemini 0 655 5 Yo Gotti Featuring Nicki Minaj 514 MIKE WILL MADE-IT (M.MIMS,O.T.MARAJ,M.WILLIAMS,T.SHAW) COCAINE MUZIK/EPIC 2 6 KENDRICK LAMAR 2 DAMN. 24 BANK ACCOUNT TOP DAWG/AFTERMATH/INTERSCOPE/IGA 576 ¡ 21 Savage 512 Debuts; 21 SAVAGE,METRO BOOMIN (S.A.JOSEPH,L.T.WAYNE,C.T.PERKINSON) SLAUGHTER GANG/EPIC 4 7 KHALID 0 American Teen 30 RIGHT HAND/RCA 367 WILD THOUGHTS 2 DJ Khaled Feat. -

Yearling & Thoroughbred Sale

OUTSIDE BACK COVER OUTSIDE FRONT COVER MAGIC MILLIONS THOROUGHBRED OF BOURBONS WINTER YEARLING & THOROUGHBRED SALE PERTH 2018 PERTH WINTER YEARLING & THOROUGHBRED SALE 24 JUNE 2018 BELMONT PARK SALES COMPLEX, PERTH, WESTERN AUSTRALIA CRAFTED CAREFULLY. DRINK RESPONSIBLY. WOODFORD RESERVE KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON WHISKEY, 40% ALC. BY VOL., THE WOODFORD RESERVE DISTILLERY, VERSAILLES, KY ©2018. WOODFORD RESERVE IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK. ©2018 BROWN-FORMAN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PERTH WINTER YEARLING SALE 24 JUNE 2018 SELLING SCHEDULE Sunday 24 June ............................................ Lots 1-40 ..................................................... 11am Supplementary Yearling Lots 152-155 will follow Lot 40 PERTH WINTER THOROUGHBRED & RACEHORSE SALE 24 JUNE 2018 SELLING SCHEDULE Sunday 24 June ............................................ Broodmares ...............................Lots 41-90 Supplementary Broodmare Lot 156 will follow Lot 90 Sunday 24 June ............................................ Weanlings .................................Lots 91-151 Supplementary Weanling Lots 157-158 will follow Lot 151 Sunday 24 June ............................................ Racehorses .........................Lots 161-195 Supplementary Racehorses will follow Lot 195 All pedigrees, supplementary pedigrees and indexes are supplied by Arion Pedigrees Limited for use by Magic Millions Sales Pty Limited under license. They are subject to copyright law, use outside a Magic Millions publication is illegal without written permission granted by -

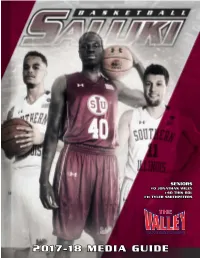

2017-18 MEDIA GUIDE Siusalukis.Com

SENIORS #0 JONATHAN WILEY #40 THIK BOL #11 TYLER SMITHPETERS 2017-18 MEDIA GUIDE SIUSalukis.com 0 Jonathan Wiley 3 Marcus Bartley 4 Eric McGill 10 Aaron Cook 6-7, 201, Senior, F 6-5, 193, Junior, G 6-2, 175, Junior, G 6-2, 185, Sophomore, G 11 Tyler Smithpeters 13 Sean Lloyd 15 Austin Weiher 22 Armon Fletcher 6-4, 203, Senior, G 6-5, 210, Junior, G 6-8, 205, Junior, F 6-5, 207, Junior, G 24 Rudy Stradnieks 24 Brendon Gooch 33 Kavion Pippen 40 Thik Bol 6-9, 229, Junior, F 6-5, 204, Freshman, F 6-10, 240, Junior, C 6-8, 202, Senior, F COACHING STAFF Barry Hinson Anthony Beane Sr. Brad Autry Justin Walker John Clancy Head Coach (6th year) Assistant (6th Year) Assistant (3rd Year) Assistant (4th Year) Operations (3rd Year) NCAA TOURNAMENT IN 1977, 93, 94, 95, 02, 03, 04, 05, 06, 07 @SIU_Basketball Contents Schedule Intro to Saluki Basketball Day Date Opponent Location Time (CT) Watch Radio/TV Roster .......................IFC Nov. 4 Sat. Rockhurst (EX) Carbondale, Ill. 7 PM Numerical Roster .........................1 Nov. 10 Fri. at Winthrop Rock Hill, S.C. 6 PM Big South Network Schedule ......................................1 Nov. 18 Sat. Illinois-Springfield Carbondale, Ill. 7 PM ESPN3 SIU Arena ..................................2-7 ESPN Gameday .........................8-9 Nov. 21 Tues. at Louisville Louisville, Ky. 6 PM RSN 1967 NIT Championship .......10-11 Nov. 25 Sat. at Murray State Murray, Ky. 7 PM OVC Network 1977 Sweet 16 ...........................12 Nov. 29 Wed. SIUE Carbondale, Ill. 7 PM ESPN3 Rich Herrin Era ..........................13 Dec. -

New Saturday Night Show to Debut with Live Format with Later Timeslot, a Money-Generator (Shotgun Saturday Ppvs.) the Ratings Were Disappointing for the Program

Issue No. 667 • August 25, 2001 New Saturday night show to debut with live format With later timeslot, a money-generator (Shotgun Saturday PPVs.) The ratings were disappointing for the program. The cable industry didn’t respond with open Another element working against Excess WWF may attempt to arms to McMahon’s concept, delaying the launch succeeding today is the lackluster performance of date to the beginning of the next year. With limited MTV Heat. Since switching from USA to MTV push limits, but will they PPV channels, Shotgun would often be preempted last fall, Heat’s ratings have dropped substantially. by bigger Saturday night events such as boxing, The USA format featured first–run matches and a learn from the past? plus live concerts (which cable at the time hoped traditional wrestling show format. The MTV would grow into a big additional revenue source). format features less wrestling and more produced HEADLINE ANALYSIS There was also skepticism whether features (music videos, highlight By Wade Keller, Torch editor the WWF could offer a product that reels, sit-down chats, etc.). History would indicate that the new Excess would draw enough interest to So far, there are no signs that program that the WWF is debuting this Saturday make it worth their while. Excess will be remarkably night on TNN will not work. The program, which The WWF ultimately couldn’t different than a mix of the is scheduled to be a compilation highlight show convince cable operators to go for weekend morning shows it with live transition segments featuring WWF the concept. -

EU Page 01 COVER.Indd

JACKSONVILLE david bazan interview | aqua grill restaurant review | d.l. hughley interview | wedding singer on broadway free weekly guide to entertainment and more | november 1-7, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 november 1-7, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents feature Sea & Sky Spectacular ..........................................................................................................PAGE 15 Greater Jacksonvile Fair ................................................................................................. PAGES 16-20 movies Movies in Theaters this Week ............................................................................................ PAGES 6-8 American Gangster (movie review) ..........................................................................................PAGE 6 The Darjeeling Limited (movie review) .....................................................................................PAGE 7 Bee Movie (movie review) .......................................................................................................PAGE 8 Lars and the Real Girl (movie review) ......................................................................................PAGE 9 home Netscapades .........................................................................................................................PAGE 10 Video Games .......................................................................................................................PAGE 11 dish Aqua Grill (restaurant review) ....................................................................................... -

Quality Control Album Download the Most Essential Songs from ‘Quality Control: Control the Streets, Vol

quality control album download The Most Essential Songs From ‘Quality Control: Control The Streets, Vol. 2,’ Ranked. Quality Control Music released its second compilation album, Quality Control: Control the Streets, Vol. 2 , last Friday and with a whopping 36 tracks, it can be a bit of a daunting listen. In fact, I’ll snag some low-hanging fruit here and say that it could have used a little quantity control as well. As album tracklists continue to balloon in the wake of music charts giving more weight to streaming tallies, a project like Control the Streets, Vol. 2 was almost inevitable. Here’s the thing, though: With so many tracks, it can seem hopelessly impossible to get a handle on which songs are truly essential listening and which are filler to pad out the streaming totals and help push the project to a more favorable chart position. For what it’s worth, the label’s assembly line-style recording strategy, in which records are churned out as quickly as they can be produced, written, and recorded, has both helped and hindered the label’s success over the past few years. After the initial success of Control the Streets, Vol. 1 in launching the burgeoning careers of Quality Control artists like City Girls and Lil Baby, the two-a-year album release schedule saw diminishing returns. Since so many of the tracks on albums from Lil Yachty, each of the individual Migos, and Lil Baby felt interchangeable, the pace began to wear on listeners, who barely registered some of the late-2018 projects from the label. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93490036000048 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code ( except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2 00 6 Department of the Treasury -The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service A For the 2006 calendar year, or tax year beginning 09 -01-2006 and ending 08-31-2007 C Name of organization D Employer identification number B Check if applicable Please Easter Seals Inc 1 Address change use IRS 36-2171729 label or Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number (- Name change print or type . See 230 West Monroe Street No 1800 (312)726 - 6200 F Initial return S p ecific Instruc - City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 FAccounting method fl Cash F Accrual (- Final return tions . Chicago, IL 606064802 Other (specify) 0- F-Amended return (- Application pending * Section 501(c)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? (- Yes F No H(b) If "Yes" enter number of affiliates 0- G Web site: 1- wwweastersealscom H(c) Are all affiliates included? (- Yes F_ No (If "No," attach a list See instructions ) I Organization type (check only one) 1- F 95 501(c) (3) -4 (insert no ) 1 -

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲一覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「ま」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲一覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「ま」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 一秒ごとの瞬間を Mye うれしかったことが悲しくて Mye 誓いのうた Mye 涙さえもう一度 Mye ふたつの片想い (feat.May J./WISE) Mye ザ・ベスト・オブ・ミー feat.ジェイダキッス (feat.ジェイダキッス) マイア フリー [Album Version] マイア マイ・ファースト・ナイト・ウィズ・ユー マイア マイ・ラヴ・イズ・ライク… WO マイア ムーヴィン・オン(リミックス) (feat.SILKK THE SHOCKER) マイア ongaku [Love human ver.] マイア・バルー Gelem Gelem [Love human ver.] マイア・バルー ワルツ [Love human ver.] マイア・バルー おはよう、おやすみ featuring かしわ マイアミパーティ つれづれ マイアミパーティ Unchain Maica_n Unknown (Maica_n〜One 4 All〜Live at ShowBoat, 2020/12/4) Maica_n Hanakoさん (Maica_n〜One 4 All〜Live at ShowBoat, 2020/12/4) Maica_n Baby it's you (LIVE 2020〜Approach to... at Music Club JANUS) Maica_n Mind game Maica_n Mind game (LIVE 2020〜Approach to... at Music Club JANUS) Maica_n replica Maica_n Our God マイカ・スタンプリー どこでもスタート まいきち One Night In Ibiza (Extended Mix) Mike Candys feat. Evelyn & Patrick Miller I Took A Pill In Ibiza [Seeb Remix] マイク・ポズナー I Took A Pill In Ibiza [Live From Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve 2017] マイク・ポズナー In The Arms Of A Stranger [Live From Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve マイク・ポズナー 2017] Slow It Down マイク・ポズナー Song About You [Live] マイク・ポズナー Nothing Is Wrong マイク・ポズナー Be As You Are マイク・ポズナー Look What I've Become (feat.Ty Dolla $ign) マイク・ポズナー Legacy マイク・ポズナー,タリブ・クウェリ I'll Get Along マイケル・キワヌーカ Hero マイケル・キワヌーカ Home Again マイケル・キワヌーカ Bones マイケル・キワヌーカ You Ain't The Problem マイケル・キワヌーカ One More Night マイケル・キワヌーカ Money マイケル・キワヌーカ,トム・ミッシュ Earth Song (Official Video) Michael Jackson Another Part of Me (Official Video) Michael Jackson -

Chapter 1: Time to Play the Game!

CHAPTER 1: TIME TO PLAY THE GAME! “Welcome to Know Your Role This is Ji m Ross, with my partner Jerry ‘The King’ Lawler, and we’re coming to you live!” “I can’t wait to get started, J. R. I haven’t been this excited si nce the divas invited me to their party last week after the show!” “I’m pumped too, King! It’s loaded top to bottom with great matches, featuring all your favorit e WWE superstars, and newcomers ready to carve their names into the annals of sports entertainment! Brace yourselves, folks, ‘cuz this is gonna be a slobber- knocker, and it all starts, next!” HERE, IN THIS VERY RING! You’re about to experience Know Your Role, the OGL roleplaying game that thrusts you into the bodyslamming, piledriving, high-octane world of sports entertainment! You can play your favorite WWE superstar or create your own wrestler and lay your brand of smack down in your quest for that ten pounds of championship gold. All you need are a handful of dice, a character sheet, and some jabronies gutsy enough to get into a match with you. Oh, and you’ll need one other thing too: attitude! Each game session of Know Your Role is a single event, such as Velocity, SmackDown!, Raw, or even a pay-per-view extravaganza like Wrestlemania. During the course of a show, anything can happen — backstage sneak attacks, ringside brawls, surprise betrayals, and, of course, pulse-pounding wrestling matches! All this and more can occur in any game session! Just like the real WWE, nothing is static in this game. -

TANGO STAR Barns 433 (ONTARIO ELIGIBLE) 1-2 BAY COLT Foaled March 1, 2013 Tattoo No

Consigned by Preferred Equine Marketing, Inc., Agent, Briarcliff Manor, New York Raised at Starmaker Farm, Cynthiana, Kentucky TANGO STAR Barns 433 (ONTARIO ELIGIBLE) 1-2 BAY COLT Foaled March 1, 2013 Tattoo No. 6LM774 Abercrombie p,4,1:53 Artsplace p,4,1:49.2 -------------------- Miss Elvira p,2,2:00.1f Sportswriter p,3,1:48.3 ----------------- Jate Lobell p,3,1:51.2 Precious Beauty p,2,1:53.3 ---------- Dominique Semalu p,3,1:56.2f TANGO STAR Western Hanover p,3,1:50.4 Western Terror p,3,1:48.3 ------------ Arterra p,2,1:53.4 Dancin Like A Star ---------------------- Dragon's Lair p,1:51.3 Dragon Temper p,3,1:57.1h --------- Almahurst Town 1st Dam DANCIN LIKE A STAR by Western Terror. Unraced. First colt. From 2 previous foals, dam of 1 winner, 1 in 1:58, including: ZUMBA STAR (M) p,2,Q1:57.3-‘14 ($2,040) (Sportswriter). Record at 2. Salsa Star (M) ($74,440) (Jenna's Beach Boy). At 2, second in leg and Final Kentucky Sires S. at Lexington; third in leg Kentucky Sires S. at Lexington. Now 3. 2nd Dam DRAGON TEMPER p,2,2:00.2; 3,1:57.1h ($25,545) by Dragon's Lair. 3 wins at 2 and 3. At 3, second in leg Genesis Ser. at Hoosier, leg White River Ser. at Hoosier; third in leg Genesis Ser. at Hoosier, 2 legs Adios Ser. at Hoosier, leg White River Ser. at Hoosier. From 11 foals, dam of 6 winners, 2 in 1:50, 5 in 1:55, 6 in 1:57, including: ST PETE STAR p,2,1:58.1; 3,1:52.3h; 1:49.2f ($579,035) (Life Sign).