It Appears That the Call-And- Response As a Linguistic Operator Signaling Cultural Information Is Vibrantly Alive in a Medium More Often Praised for Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

Only Believe Song Book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, Write To

SONGS OF WORSHIP Sung by William Marrion Branham Only Believe SONGS SUNG BY WILLIAM MARRION BRANHAM Songs of Worship Most of the songs contained in this book were sung by Brother Branham as he taught us to worship the Lord Jesus in Spirit and Truth. This book is distributed free of charge by the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, with the prayer that it will help us to worship and praise the Lord Jesus Christ. To order the Only Believe song book from the SPOKEN WORD PUBLICATIONS, write to: Spoken Word Publications P.O. Box 888 Jeffersonville, Indiana, U..S.A. 47130 Special Notice This electronic duplication of the Song Book has been put together by the Grand Rapids Tabernacle for the benefit of brothers and sisters around the world who want to replace a worn song book or simply desire to have extra copies. FOREWARD The first place, if you want Scripture, the people are supposed to come to the house of God for one purpose, that is, to worship, to sing songs, and to worship God. That’s the way God expects it. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS, January 3, 1954, paragraph 111. There’s something about those old-fashioned songs, the old-time hymns. I’d rather have them than all these new worldly songs put in, that is in Christian churches. HEBREWS, CHAPTER SIX, September 8, 1957, paragraph 449. I tell you, I really like singing. DOOR TO THE HEART, November 25, 1959. Oh, my! Don’t you feel good? Think, friends, this is Pentecost, worship. This is Pentecost. Let’s clap our hands and sing it. -

Jennifer Hudson SEPTEMBER 3 0 OCTOBER OCTOBER 7 OCTOBER

Jennifer Hudson Chemical" and "No News Is Bad News." "It's a nice marriage of where I've come from and where I've gotten to. For me, it's the "I think people will be pleasantly surprised, because it shows a track that ties all the ends together," he says of the latter. side of my work that no one has heard before," Jennifer Hudson says of her long -in- the -works debut. First single "Spotlight," Xtreme penned by Ne -Yo, is top 40 on Billboard's Hot R &B /Hip -Hop TBA (Universal) Songs chart after seven weeks. While a follow -up hasn't been The Bronx urban bachata duo's breakout, " Haciendo Historia," chosen, some tracks in contention are the Timbaland- produced has sold 125,000 copies in the United States and Puerto Rico, ac- "Pocketbook" featuring Ludacris and "Can't Stop the Rain," also cording to Nielsen SoundScan, and spawned hits "Shorty Shorty" written by Ne -Yo. Additional contributors to the and "No Me Digas Que No." Steve Styles and Danny D. (the for- album include Robin Thicke, the Under- mer won an AS CAP Latino Award this year for penning "Shorty dogs, Diane Warren, Christopher Shorty") are producing and writing their follow -up with produc- "Tricky" Stewart and Jack ers Sergio George, George Zamora and manager Ben de Jesus. Splash. R. Kelly and Akon It's "still within the urban bachata realm but a little more tradi- are expected to con- tional," de Jesus says. Referencing everything from salsa to clas- tribute as well. sic Dominican bachata to hip -hop and Sean Kingston, "the fusion is going even deeper between modern and retro," he says. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

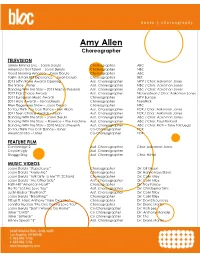

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

Diddy Ft Chris Brown Lyrics

Diddy ft chris brown lyrics Yesterday Lyrics: Yesterday I fell in love, today feels like my funeral / I just got hit by a bus, shouldn't Featuring Chris Brown [Verse 1: Diddy & Chris Brown]. Lyrics to "Yesterday" song by Diddy - Dirty Money: Yesterday I fell in love Diddy - Dirty Money Lyrics. "Yesterday" (feat. Chris Brown). [Chorus - Chris Brown]. So I just made an Instagram and a Twitter, It would make me happy if everyone went and followed me. Here are. Music video by Diddy - Dirty Money performing Yesterday. One reason why I love Chris Brown is 1:He. Lyrics of YESTERDAY by Puff Daddy feat. Chris Brown and Dirty Money: Chorus Chris Brown, Yesterday I fell in love, Today [Verse 1: Diddy]. Lyrics for Yesterday by Diddy - Dirty Money feat. Chris Brown. [Chorus- Chris Brown] Yesterday I fell in love Today feels like my funeral I just got. Yesterday Songtext von Diddy - Dirty Money feat. Chris Brown mit Lyrics, deutscher Übersetzung, Musik-Videos und Liedtexten kostenlos auf Yesterday (feat Diddy Dirty Money) lyrics performed by Chris Brown: [Refrain/Couplet 1 - Chris Brown] Yesterday I fell in love Today feels like my funeral I just got. Diddy-Dirty Money - Yesterday Lyrics ft. Chris Brown [Chorus- Chris Brown] Yesterday I fell in love Today feels like my funeral I just got hit b. [Chorus- Chris Brown] Yesterday I fell in love. Today feels like my funeral. I just got hit by a bus. Shouldn've been so beautiful. Don't know why I gave my heart. Lyrics to 'Yesterday (Feat Chris Brown)' by DIDDY: [Chorus- Chris Brown] / Yesterday I fell in love / Today feels like my funeral / I just got hit by a bus. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura

The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura L. Bunting-Hudson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Laura L. Bunting-Hudson All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia Laura L. Bunting-Hudson How do rap artists in Bogota, Colombia come together to make music? What is the process they take to commodify their culture? Why are some rappers able to become socially mobile in this process, while others are less so? What is technology’s role in all of this? This ethnography explores those questions, as it carefully documents the strategies utilized by various rap groups in Bogota, Colombia to create social mobility, commoditize products and to create a different vision of modernity within the hip-hop community, as an alternative to the ideals set forth by mainstream Colombian society. Resistance Art Poetry (RAP), is said to have originated in the United States but has become a form of international music. In conducting ethnographic research from December of 2012 to October 2014, I was able to discover how rappers organize themselves politically, how they commoditize their products and distribute them to create various types of social mobilities. In this dissertation, I constructed models to typologize rap groups in Bogota, Colombia, which I call polities of rappers to discuss how these groups come together, take shape, make plans and execute them to reach their business goals. -

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

Black Rage VI Denison University

Denison University Denison Digital Commons Writing Our Story Black Studies 2005 Black Rage VI Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/writingourstory Recommended Citation Denison University, "Black Rage VI" (2005). Writing Our Story. 98. http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/writingourstory/98 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Black Studies at Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Writing Our Story by an authorized administrator of Denison Digital Commons. ~It ...... 1 ei ll e:· CU· st. C jll eli [I C,I ei l .J C.:a, •.. a4 II a.il .. a,•• as II at iI Uj 'I Uj iI ax cil ui 11 a: c''. iI •a; a,iI'. u,· u,•• a: • at , 3,,' .it Statement of Purpose: To allow for a creative outlet for students of the Black Student Union of Denison University. Dedicated to Introduction The Black Student Union The need for this publication came about when the expres· Spring 2005 sions of a number of Black students were denied from other campus publications without any valid justification. As his tory has proven, when faced With limitations, we as Black people then create a means for overcoming that limitation a means that is significant to our own interests and beliefs. Therefore, we came together as a Black community in search of resolution, and decided on Black Rage as the instrument by which we would let our creative voices sing. This unprecedented publication serves as a refuge for the Black students at Denison University, by offering an avenue for our poetry, prose, short stories as well as other unique writings to be read, respected, and held in utmost regard.