Promoting Innovation in the Mediterranean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Data Everywhere, and No SQL in Sight Editorial: from SIGKDD Chairman Usama M

Big Data Everywhere, and No SQL in Sight Editorial: from SIGKDD Chairman Usama M. Fayyad Chairman, SIGKDD Executive Committee Executive Chairman, Oasis500 – www.oasis500.com Chairman & CTO, Blue Kangaroo (ChoozOn Corp) [email protected] ABSTRACT traditional data storage and management state-of-the-art. Usually these limits are tested on 3 major fronts: the 3-V’s: Volume, As founding editor-in-chief of this publication, I used to Velocity, and Variety. I like to talk about the 4-V’s of data systematically address our readers via regular editorials. In mining, where the 4th V stands for Value: delivering insights and discussions with the current Editor-in-Chief, Bart Goethals, we business value from the data. More on this topic in a future decided that it may be a good idea to restore the regular editorial Editorial. For now, I would like to focus on some of the section from me as SIGKDD Chairman/director. So this is a first opportunities and threats arising from this developing situation. in what hopefully will be a regularly occurring event. This Editorial contribution discusses the issues facing the fields of data 2. BREAKDOWN IN THE RELATIONAL mining and knowledge discovery, including challenges, threats DATABASE WORLD and opportunities. In this Editorial we focus on the emerging area While most relational database researchers and practitioners are of BigData and the concerns that we are not contributing at the still living in denial about what is going on, what I am witnessing level we should to this important field. We believe we have a is nothing short of a major breakdown. -

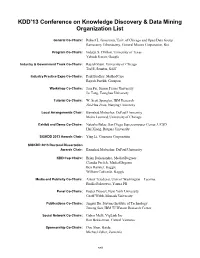

Organization List

KDD’13 Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining Organization List General Co-Chairs: Robert L. Grossman, Univ. of Chicago and Open Data Group Ramasamy Uthurusamy, General Motors Corporation, Ret. Program Co-Chairs: Inderjit S. Dhillon, University of Texas Yehuda Koren, Google Industry & Government Track Co-Chairs: Rayid Ghani, University of Chicago Ted E. Senator, SAIC Industry Practice Expo Co-Chairs: Paul Bradley, MethodCare Rajesh Parekh, Groupon Workshop Co-Chairs: Jian Pei, Simon Fraser University Jie Tang, Tsinghua University Tutorial Co-Chairs: W. Scott Spangler, IBM Research Zhi-Hua Zhou, Nanjing University Local Arrangements Chair: Bamshad Mobasher, DePaul University Meira Leonard, University of Chicago Exhibit and Demo Co-Chairs: Natasha Balac, San Diego Supercomputer Center, UCSD Hui Xiong, Rutgers University SIGKDD 2013 Awards Chair: Ying Li, Concurix Corporation SIGKDD 2013 Doctoral Dissertation Awards Chair: Bamshad Mobasher, DePaul University KDD Cup Chairs: Brian Dalessandro, Media6Degrees Claudia Perlich, Media6Degrees Ben Hamner, Kaggle William Cukierski, Kaggle Media and Publicity Co-Chairs: Ankur Teredesai, Univ of Washington – Tacoma Emilia Palaveeva, Yantra PR Panel Co-Chairs: Foster Provost, New York University Geoff Webb, Monash University Publications Co-Chairs: Jingrui He, Stevens Institute of Technology Jimeng Sun, IBM TJ Watson Research Center Social Network Co-Chairs: Gabor Melli, VigLink Inc Ron Bekkerman, Carmel Ventures Sponsorship Co-Chairs: Dou Shen, Baidu Michael Zeller, Zementis xxii Treasurer: -

Conference Program

The Third International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining August 14–17 1997, Newport Beach, California Sponsored by the American Association for Artificial Intelligence Cosponsored by General Motors Research, The National Institute for Statistical Sciences, and NCR Corporation In cooperation with The American Statistical Association Welcome to KDD-97! KDD-97 Organization General Conference Chair William Eddy, Carnegie Mellon Sally Morton, Rand Corporation University Richard Muntz, University of California Ramasamy Uthurusamy, General Motors Charles Elkan, University of California at at Los Angeles Corporation San Diego Raymond Ng, University of British Usama Fayyad, Microsoft Research Columbia Program Cochairs Ronen Feldman, Bar-Ilan University, Steve Omohundro, NEC Research David Heckerman, Microsoft Research Israel Gregory Piatetsky-Shapiro, Heikki Mannila, University of Helsinki, Jerry Friedman, Stanford University GTE Laboratories Finland Dan Geiger, Technion, Israel Daryl Pregibon, Bell Laboratories Daryl Pregibon, AT&T Laboratories Clark Glymour, Carnegie Mellon Raghu Ramakrishnan, University of University Wisconsin, Madison Publicity Chair Moises Goldszmidt, SRI International Patricia Riddle, Boeing Computer Georges Grinstein, University of Services Paul Stolorz, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Massachusetts, Lowell Ted Senator, NASD Regulation Inc. Tutorial Chair Jiawei Han, Simon Fraser University, Jude Shavlik, University of Wisconsin at Canada Madison Padhraic Smyth, University of California, David Hand, Open University, -

Thèses Et HDR 2015

UMR 5205 CNRS Thèses et HDR 2015 Laboratoire d’InfoRmatique en Image et Systèmes d’information Sommaire HDR Graphes et Jeux combinatoires Eric Duchêne ............................................................................................................................. 7 Des pixels à la signification Elöd Egyed-Zsigmond ............................................................................................................ 11 Analyse des usages des plateformes de construction de connaissances par des méthodes mixtes et réflexives pour l’amélioration de l’appropriation et de la structuration de l’information Christine Michel ...................................................................................................................... 17 Thèses Data collection optimization in Wireless Sensor Networks, application to the Everblu smart metering Network Besem Abid ............................................................................................................................. 21 Web services composition in uncertain environments Soumaya Amdouni ................................................................................................................. 23 Automatic Prediction of Emotions Induced by Movies Yoann Baveye .......................................................................................................................... 25 Configuration automatique d’un solveur générique intégrant des techniques de décomposition arborescente pour la résolution de problèmes de satisfaction de contraintes -

Ensemble Learning for Ranking Interesting Attributes

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 Ensemble learning for ranking interesting attributes Erik W. Sinsel West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sinsel, Erik W., "Ensemble learning for ranking interesting attributes" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 1685. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/1685 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ensemble Learning for Ranking Interesting Attributes Erik W. Sinsel Thesis submitted to the College of Engineering and Mineral Resources at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science Bojan Cukic, Ph.D., Chair Frances Van Scoy, Ph.D. John Atkins, Ph.D. Lane Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering Morgantown, West Virginia 2005 Abstract Machine learning knowledge representations, such as decision trees, are often incomprehensible to humans. They can also contain errors specific to the representation type and the data used to generate them. -

Session at AAAS Annual Meeting

SESSION on DESIGN THINKING TO MOBILIZE SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION FOR SOCIAL CHALLENGES The aim of this symposium is to highlight the innova- tive approaches towards address social challenges. There has been growing interest in promoting “social innovation” to imbed innovation in the wider economy by fostering opportunities for new actors, such as non-profit foundations, to steer research and collaborate with firms and entrepreneurs and to tackle social challenges. User and consumers are also relevant as they play an important role in demanding innovation for social goals but also as actors and suppliers of solutions. Although the innovation process is now much more open and receptive to social influences, progress on social innovation will call for the greater involvement of stakeholders who can mobilize science, technol- ogy and innovation to address social challenges. Thus, the session requires to be approached from holistic and multidisciplinary mind and needs to cover the issue from different aspects by seven inter- national speakers. Contents Overview ■1 Program ■4 Session Description ■6 Outline of Presentation ■7 Lecture material ■33 Appendix ■55 Program Welcome and Opening 8:30-8:35 • Dr. Yuko Harayama, Deputy Director of the OECD’s Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry (DSTI) ● (moderator) (5min) Session 1: Putting ‘design thinking’ into practice 8:35-9:20 • Dr. Karabi Acharya, Change Leader, Ashoka, USA(15min) ● Systemic Change to Achieve Environmental Impact and Sustainability • Mr. Tateo Arimoto, Director-General, Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society, Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST / RISTEX) (Co-organiser and Host), Japan (15min) Design Thinking to Induce new paradigm for issue-driven approach −Discussant (5min) • Dr. -

London, United Kingdom August 19 ‑ 23, 2018 24Th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining

London, United Kingdom August 19 ‑ 23, 2018 24th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining PRELIMINARY PROGRAM Contents KDD 2018 Agenda at a Glance KDD 2018 Chairs’ Welcome Message Program Highlights KDD 2018 Tutorial Program KDD 2018 Health Day Program KDD 2018 Workshop Program KDD 2018 Deep Learning Day Program KDD 2018 Hands‑On Tutorial Program KDD Cup 2018 Program KDD 2018 Project Showcase Program KDD 2018 Conference Program KDD 2018 Conference Organization KDD 2018 Sponsors & Supporters Useful Links and Emergency Contacts KDD 2018 Agenda at a Glance KDD 2018: Sunday, August 19 (TUTORIAL DAY) 7:00AM ‑ 5:00PM KDD 2018 Registration Boulevard (Level 0) 8:00AM ‑ 12:00PM T1: Graph and Tensor Mining for Fun and Profit ICC Capital Suite Room 7 (Level 3) T2: Privacy‑preserving Data Mining in Industry: Practical 8:00AM ‑ 12:00PM Challenges and Lessons Learned ICC Capital Suite Room 9 (Level 3) T4: Graph Exploration: Let me Show what is Relevant in 8:00AM ‑ 12:00PM your Graph ICC Capital Suite Room 12 (Level 3) T8: Online Evaluation for Effective Web Service 8:00AM ‑ 12:00PM Development ICC Capital Suite Room 6 (Level 3) T9: Redescription Mining: Theory, Algorithms, and 8:00AM ‑ 12:00PM Applications ICC Capital Suite Room 16 (Level 3) T11: Anti‑discrimination Learning: From Association to 8:00AM ‑ 12:00PM Causation ICC Capital Suite Room 1 (Level 3) T15: Graph Sketching, Sampling, Streaming, and 8:00AM ‑ 12:00PM Space‑Efficient Optimization ICC Capital Suite Room 15 (Level 3) 8:00AM ‑ 12:00PM T17: Artificial Intelligence -

Partners for a New Beginning Status Report | January 2013 Table of Contents

PARTNERS FOR A NEW BEGINNING STATUS REPORT | JANUARY 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS A Letter from the Chairs 2 Looking Ahead to 2013 4 Projects & Local Chapter Overviews 6 Algeria 6 Egypt 8 Indonesia 10 Jordan 12 Mauritania 15 Morocco 16 Pakistan 18 Palestinian Territory 22 Tunisia 27 Turkey 29 Maghreb 32 Global 34 What We’re Doing 36 2012 Convenings and Partner Events 36 2012 Delegations 42 Upcoming in 2013 43 PNB Leadership 44 PNB Steering Committee 44 PNB-NAPEO Advisory Board 44 PNB Secretariat: Roles and Responsibilities 45 PNB Timeline(2010–2012) 46 PNB Statement of Commitment, Clinton Global Initiative, September 2010 47 PARTNERS FOR A NEW BEGINNING STATUS REPORT | JANUARY 2013 As Partners for a New Beginning (PNB) concludes its second year, we would like to take a moment to reflect on our collaborative work and take stock of our achievements. Our goal is to capitalize upon the momentum and success of this past year, to secure tangible results as we continue moving forward. A LETTER PNB can look proudly on the accomplishments of the last 12 months. They have contributed significantly to our mission. Our launch last year of local chapters in Jordan and Mauritania FROM THE CHAIRS attests to the sustained efforts of our partners abroad, the invaluable leadership of our Steering Committee, the instrumental support from the PNB Secretariat, and our partnership with the U.S. Department of State, codified recently in a renewed Memorandum of Understanding. With the help of its partners, PNB has launched, expanded, or pledged support for more than 180 projects since the partnership began in September 2010. -

Science Without Borders 17–21 February, Washington, D.C

Preliminary Press Program Join Us in Washington, D.C. for Science and Fun Cover symposia on the implications of finding other worlds, the next steps in brain-computer interfaces, frontiers in chemistry, the next big solar storm, and more. Talk to leaders in science, technology, engineering, education, and policy-making. Gather story ideas for the year ahead. Mingle with colleagues at receptions and social events. It’s all available at the world’s largest interdisciplinary science forum. 2011 AAAS Annual Meeting Science Without Borders 17–21 February, Washington, D.C. CURRENT AS OF 1 NOVEMBER 2010 1 2011 AAAS Annual Meeting Science Without Borders Dear Colleagues, On behalf of the AAAS Board of Directors, it is my distinct honor to invite you to the 177th Meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). The Annual Meeting is one of the most widely recognized pan-science events, with hundreds of networking oppor- tunities and broad global media coverage. An exceptional array of speakers and attendees will gather at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C. You will have the opportunity to interact with scientists, engineers, educators, and policy-makers who will present the latest thinking and developments in their areas of expertise. The meeting’s theme — Science Without Borders — integrates interdisciplinary science, across both research and teaching, that utilizes diverse approaches as well as the diversity of its practitioners. The program will highlight science and teaching that cross conventional borders or break out from silos, especially in ground-breaking areas of research that highlight new and exciting developments in support of science, technology, and education. -

The KDD Process for Extracting Useful Knowledge from Volumes of Data

Knowledge Discovery in Databases creates the context for developing the tools needed to control the flood of data facing organizations that depend on ever-growing databases of business, manufacturing, scientific, and personal information. The KDD Process for Extracting Useful Knowledge from Volumes of Data AS WE MARCH INTO THE AGE of digital information, the problem of data overload Usama Fayyad, looms ominously ahead. Our ability to analyze and Gregory Piatetsky-Shapiro, understand massive datasets lags far behind and Padhraic Smyth our ability to gather and store the data. A new gen- eration of computational techniques and many more applications generate and tools is required to support the streams of digital records archived in extraction of useful knowledge from huge databases, sometimes in so-called the rapidly growing volumes of data. data warehouses. These techniques and tools are the Current hardware and database tech- subject of the emerging field of knowl- nology allow efficient and inexpensive edge discovery in databases (KDD) and reliable data storage and access. Howev- data mining. er, whether the context is business, Large databases of digital informa- medicine, science, or government, the tion are ubiquitous. Data from the datasets themselves (in raw form) are of neighborhood store’s checkout regis- little direct value. What is of value is the ter, your bank’s credit card authoriza- knowledge that can be inferred from tion device, records in your doctor’s the data and put to use. For example, office, patterns in your telephone calls, the marketing database of a consumer TERRY WIDENER COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM November 1996/Vol. -

Course Summary

ANLY600 STUDENT WARNING: This course syllabus is from a previous semester archive and serves only as a preparatory reference. Please use this syllabus as a reference only until the professor opens the classroom and you have access to the updated course syllabus. Please do NOT purchase any books or start any work based on this syllabus; this syllabus may NOT be the one that your individual instructor uses for a course that has not yet started. If you need to verify course textbooks, please refer to the online course description through your student portal. This syllabus is proprietary material of APUS. Course Summary Course : ANLY600 Title : Data Mining Length of Course : 8 Prerequisites : N/A Credit Hours : 3 Description Course Description: This course covers data mining using the R programming language. It offers hands on experience approach through a learn-by-doing-it strategy. It further integrates data mining topics with applied business analytics to address real world data mining cases. It continues the examination of the role of “Data Mining in R”, and review statistics techniques in prescriptive analytics, and some predictive analytics. Additionally, some standard techniques and excel functions will be also covered. Course Scope: Data that has relevance for managerial decisions is accumulating at an incredible rate due to a host of technological advances. Electronic data capture has become inexpensive and ubiquitous as a by-product of innovations such as the internet, e-commerce, electronic banking, point-of-sale devices, bar-code readers, and intelligent machines. Such data is often stored in data warehouses and data marts specifically intended for management decision support. -

A Data Scientist's Guide to Start-Ups

ROUNDTABLE A DATA SCIENTIST’S GUIDE TO START-UPS Foster Provost,1 Geoffrey I. Webb,2 Ron Bekkerman,3 Oren Etzioni,4 Usama Fayyad,5–7 and Claudia Perlich8 Abstract In August 2013, we held a panel discussion at the KDD 2013 conference in Chicago on the subject of data science, data scientists, and start-ups. KDD is the premier conference on data science research and practice. The panel discussed the pros and cons for top-notch data scientists of the hot data science start-up scene. In this article, we first present background on our panelists. Our four panelists have unquestionable pedigrees in data science and substantial experience with start-ups from multiple perspectives (founders, employees, chief scientists, venture capitalists). For the casual reader, we next present a brief summary of the experts’ opinions on eight of the issues the panel discussed. The rest of the article presents a lightly edited transcription of the entire panel discussion. Background scientist at fast-growing Dstillery, after notable success as a data scientist at IBM. Introduced in alphabetical order, participant Ron Bekkerman (currently at the University of Haifa) was a The panel organizers/moderators were Foster Provost of venture capitalist with Carmel Ventures in Israel at the time NYU, cofounder of Dstillery, Everyscreen Media, and Integral of the panel discussion, and before that was an early data Ad Science, coauthor of the book Data Science for Business, scientist at LinkedIn. Ron is also cofounder of a stealth-stage and former editor-in-chief of the journal Machine Learning, start-up. Oren Etzioni (co)founded MetaCrawler (bought by and Geoff Webb of Monash University, founder of GI Webb Infospace), Netbot (bought by Excite), ClearForest (bought & Associates, a data science consultancy, and editor-in-chief by Reuters), Farecast (bought by Microsoft), and Decide of the journal Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery.