October 1957 Changed the Course of American Science and of My Own

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attachment 1

Appendix 1 Chemico-Biological Interactions 301 (2019) 2–5 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Chemico-Biological Interactions journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/chembioint An examination of the linear no-threshold hypothesis of cancer risk T assessment: Introduction to a series of reviews documenting the lack of biological plausibility of LNT R. Goldena,*, J. Busb, E. Calabresec a ToxLogic, Gaithersburg, MD, USA b Exponent, Midland, MI, USA c University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA The linear no-threshold (LNT) single-hit dose response model for evolution and the prominence of co-author Gilbert Lewis, who would be mutagenicity and carcinogenicity has dominated the field of regulatory nominated for the Nobel Prize some 42 times, this idea generated much risk assessment of carcinogenic agents since 1956 for radiation [8] and heat but little light. This hypothesis was soon found to be unable to 1977 for chemicals [11]. The fundamental biological assumptions upon account for spontaneous mutation rates, underestimating such events which the LNT model relied at its early adoption at best reflected a by a factor of greater than 1000-fold [19]. primitive understanding of key biological processes controlling muta- Despite this rather inauspicious start for the LNT model, Muller tion and development of cancer. However, breakthrough advancements would rescue it from obscurity, giving it vast public health and medical contributed by modern molecular biology over the last several decades implications, even proclaiming it a scientific principle by calling it the have provided experimental tools and evidence challenging the LNT Proportionality Rule [20]. While initially conceived as a driving force model for use in risk assessment of radiation or chemicals. -

Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions When Conducting Recombinant DNA Research – Case Summary M.J

International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering Case Study Series Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions When Conducting Recombinant DNA Research – Case Summary M.J. Peterson with research assistance from Paul White Version 1, June 2010 Safe laboratory practices are an important element in the responsible conduct of research. They protect scientists, research assistants, laboratory technicians, and others from hazards that can arise during experimentation. The particular hazards that might arise vary according to the type of experimentation: the explosions or toxic gases that could result from chemical experiments are prevented or contained by different kinds of measures then are used to limit the health hazards posed by working with radioactive isotopes. In most areas, scientists are allowed – and even encouraged – to decide for themselves what experiments to undertake and how to construct and run their labs. In 1970, there were three main exceptions, and they applied more to questions of how to carry out research than to selecting topics for research: use of radioactive materials, use of tumor-causing viruses, and use of human subjects. In these areas, levels of risk to persons inside and outside the lab were perceived as great enough to justify having the government, either through the regular bureaucracy or through scientific agencies, set and enforce mandatory safety standards. When genetics was poised at the threshold of recombinant DNA research and genetic manipulation techniques in the 1960s, the hazards such work might pose to lab personnel or to others were unknown. Many scientists and others believed they were likely to be significant. The primary concern in public discussion was whether hybrid organisms bred from recombinant DNA would cause new diseases or create varieties of plants or animals that would overwhelm and irretrievably change the natural environment. -

Moore Noller

2002 Ada Doisy Lectures Ada Doisy Lecturers 2003 in BIOCHEMISTRY Sponsored by the Department of Biochemistry • University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Dr. Peter B. 1970-71 Charles Huggins* and Elwood V. Jensen A76 1972-73 Paul Berg* and Walter Gilbert* Moore 1973-74 Saul Roseman and Bruce Ames Department of Molecular carbonyl Biophysics & Biochemistry Phe 1974-75 Arthur Kornberg* and Osamu Hayaishi Yale University C75 1976-77 Luis F. Leloir* New Haven, Connecticutt 1977-78 Albert L. Lehninger and Efraim Racker 2' OH attacking 1978-79 Donald D. Brown and Herbert Boyer amino N3 Tyr 1979-80 Charles Yanofsky A76 4:00 p.m. A2486 1980-81 Leroy E. Hood Thursday, May 1, 2003 (2491) 1983-84 Joseph L. Goldstein* and Michael S. Brown* Medical Sciences Auditorium 1984-85 Joan Steitz and Phillip Sharp* Structure and Function in 1985-86 Stephen J. Benkovic and Jeremy R. Knowles the Large Ribosomal Subunit 1986-87 Tom Maniatis and Mark Ptashne 1988-89 J. Michael Bishop* and Harold E. Varmus* 1989-90 Kurt Wüthrich Dr. Harry F. 1990-91 Edmond H. Fischer* and Edwin G. Krebs* 1993-94 Bert W. O’Malley Noller 1994-95 Earl W. Davie and John W. Suttie Director, Center for Molecular Biology of RNA 1995-96 Richard J. Roberts* University of California, Santa Cruz 1996-97 Ronald M. Evans Santa Cruz, California 1998-99 Elizabeth H. Blackburn 1999-2000 Carl R. Woese and Norman R. Pace 2000-01 Willem P. C. Stemmer and Ronald W. Davis 2001-02 Janos K. Lanyi and Sir John E. Walker* 12:00 noon 2002-03 Peter B. -

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

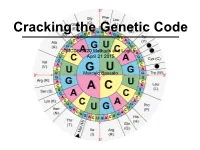

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

Maxine Singer, Date? (Sometime in Early 2015)

Oral History: Maxine Singer, date? (sometime in early 2015) CAF: Alright Donald, why don’t you start DPS: Well, when did you meet Caryl, Caryl Haskins and how did this meeting come about? MS: I think, but I’m not really sure, that the first time I met him might have been at a Yale Corporation meeting, and it was probably 1975, if I have to guess, because that’s when I went on the corporation. And he had already been a member. So I’m pretty sure I met him at that meeting. DPS: OK. I’ll go on. We have a record of his activities as President of the Carnegie Institution. What would you regard as the facets of his leadership that were most revealing about him? MS: Well, I think the most revealing thing about him was the fact that he convinced the trustees to close down the Department of Genetics. So: Could you remind me what years he was president? DPS: ’56 to ’71, I believe. MS: Right. So I think the…In my judgment anyway. Maybe other people would feel differently. But in my judgment, that was the single, most important thing he did. CAF: Why is that? DPS: What led him to do that? MS: So this is a good, an interesting question about which we have only fragmentary knowledge. The long time director of the department, whose name was Demerec, retired. And Demerec was a classical geneticist, which is something that Caryl understood. And the people who were coming up, and even some of the people who there, were beginning to study genetics as a molecular science, tied to biochemistry in various ways, which was certainly the new world and the world of science that proved to be incredibly productive. -

Cornell Alumni Magazine

c1-c4CAMja11 6/16/11 1:25 PM Page c1 July | August 2011 $6.00 Alumni Magazine Well-Spoken Screenwriter (and former stutterer) David Seidler ’59 wins an Oscar for The King’s Speech cornellalumnimagazine.com c1-c4CAMja11 6/16/11 1:25 PM Page c2 01-01CAMja11toc 6/20/11 1:19 PM Page 1 July / August 2011 Volume 114 Number 1 In This Issue Alumni Magazine 34 Corne 2 From David Skorton Farewell, Mr. Vanneman 4 The Big Picture Card sharp 6 Correspondence DVM debate 8 Letter from Ithaca Justice league 10 From the Hill Capped and gowned 14 Sports Top teams, too 16 Authors Eyewitness 32 Wines of the Finger Lakes Ports of New York “Meleau” White 18 10 52 Classifieds & 34 Urban Cowboys Cornellians in Business 53 Alma Matters BRAD HERZOG ’90 56 Class Notes Last October, the Texas Rangers won baseball’s American League pennant—and played in their first-ever World Series. Two of the primary architects of that long-sought vic- 91 Alumni Deaths tory were Big Red alums from (of all places) the Big Apple. General manager Jon 96 Cornelliana Daniels ’99 and senior director of player personnel A. J. Preller ’99 are old friends and Little house in the big woods lifelong baseball nuts who brought fresh energy to an underperforming franchise. And while they didn’t take home the championship trophy . there’s always next season. Legacies To see the Legacies listing for under- graduates who entered the University in fall 40 Training Day 2010, go to cornellalumnimagazine.com. JIM AXELROD ’85 Currents CBS News reporter Jim Axelrod has covered everything from wars to presidential cam- paigns to White House politics. -

The Gene Wars: Science, Politics, and the Human Genome

8 Early Skirmishes | N A COMMENTARY introducing the March 7, 1986, issue of Science, I. Renato Dulbecco, a Nobel laureate and president of the Salk Institute, made the startling assertion that progress in the War on Cancer would be speedier if geneticists were to sequence the human genome.1 For most biologists, Dulbecco's Science article was their first encounter with the idea of sequencing the human genome, and it provoked discussions in the laboratories of universities and research centers throughout the world. Dul- becco was not known as a crusader or self-promoter—quite the opposite— and so his proposal attained credence it would have lacked coming from a less esteemed source. Like Sinsheimer, Dulbecco came to the idea from a penchant for thinking big. His first public airing of the idea came at a gala Kennedy Center event, a meeting organized by the Italian embassy in Washington, D.C., on Columbus Day, 1985.2 The meeting included a section on U.S.-Italian cooperation in science, and Dulbecco was invited to give a presentation as one of the most eminent Italian biologists, familiar with science in both the United States and Italy. He was preparing a review paper on the genetic approach to cancer, and he decided that the occasion called for grand ideas. In thinking through the recent past and future directions of cancer research, he decided it could be greatly enriched by a single bold stroke—sequencing the human genome. This Washington meeting marked the beginning of the Italian genome program.3 Dulbecco later made the sequencing -

Members of Groups Central to the Scientists' Debates About Rdna

International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering Case Study Series: Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions Appendix C: Members of Groups Central to the Scientists’ Debates about rDNA Research 1973-76 M.J. Peterson Version 1, June 2010 Signers of Singer-Söll Letter 1973 Maxine Singer Dieter Söll Signers of Berg Letter 1974 Paul Berg David Baltimore Herbert Boyer Stanley Cohen Ronald Davis David S. Hogness Daniel Nathans Richard O. Roblin III James Watson Sherman Weissman Norton D. Zinder Organizing Committee for the Asilomar Conference David Baltimore Paul Berg Sydney Brenner Richard O. Roblin III Maxine Singer This case was created by the International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering (IDEESE) Project at the University of Massachusetts Amherst with support from the National Science Foundation under grant number 0734887. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. More information about the IDEESE and copies of its modules can be found at http://www.umass.edu/sts/ethics. This case should be cited as: M.J. Peterson. 2010. “Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions When Conducting Recombinant DNA Research.” International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering. Available www.umass.edu/sts/ethics. © 2010 IDEESE Project Appendix C Working Groups for the Asilomar Conference Plasmids Richard Novick (Chair) Royston C. Clowes (Institute for Molecular Biology, University of Texas at Dallas) Stanley N. Cohen Roy Curtiss III Stanley Falkow Eukaryotes Donald Brown (Chair) Sydney Brenner Robert H. Burris (Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin) Dana Carroll (Department of Embryology, Carnegie Institution, Baltimore) Ronald W. -

Evolution of Coenzyme BI2 Synthesis Among Enteric Bacteria

Copyright 0 1996 by the Genetics Society of America Evolution of Coenzyme BI2Synthesis Among Enteric Bacteria: Evidence for Loss and Reacquisition of a Multigene Complex Jeffrey G. Lawrence and John R. Roth Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 Manuscript received June 16, 1995 Accepted for publication October 4, 1995 ABSTRACT We have examined the distribution of cobalamin (coenzyme BI2) synthetic ability and cobalamin- dependent metabolism among entericbacteria. Most species of enteric bacteria tested synthesize cobala- min under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions and ferment glycerol in a cobalamindependent fashion. The group of species including Escha'chia coli and Salmonella typhimurium cannot ferment glyc- erol. E. coli strains cannot synthesize cobalamin de novo, and Salmonella spp. synthesize cobalamin only under anaerobic conditions. In addition, the cobalamin synthetic genes of Salmonella spp. (cob) show a regulatory pattern different from that of other enteric taxa tested. We propose that the cobalamin synthetic genes, as well asgenes providing cobalamindependent diol dehydratase, were lostby a common ancestor of E. coli and Salmonella spp. and were reintroduced as a single fragment into the Salmonella lineage from an exogenous source. Consistent with this hypothesis, the S. typhimurium cob genes do not hybridize with the genomes of other enteric species. The Salmonella cob operon may represent a class of genes characterized by periodic loss and reacquisition by host genomes. This process may be an important aspect of bacterial population genetics and evolution. OBALAMIN (coenzyme BIZ) is a large evolution- The cobalamin biosynthetic genes have been charac- C arily ancient molecule ( GEORGOPAPADAKOUand terized in S. -

15/5/40 Liberal Arts and Sciences Chemistry Irwin C. Gunsalus Papers, 1877-1993 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Irwin C

15/5/40 Liberal Arts and Sciences Chemistry Irwin C. Gunsalus Papers, 1877-1993 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Irwin C. Gunsalus 1912 Born in South Dakota, son of Irwin Clyde and Anna Shea Gunsalus 1935 B.S. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1937 M.S. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1940 Ph.D. in Bacteriology, Cornell University 1940-44 Assistant Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1944-46 Associate Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1946-47 Professor of Bacteriology, Cornell University 1947-50 Professor of Bacteriology, Indiana University 1949 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1950-55 Professor of Microbiology, University of Illinois 1955-82 Professor of Biochemistry, University of Illinois 1955-66 Head of Division of Biochemistry, University of Illinois 1959 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1959-60 Research sabbatical, Institut Edmund de Rothchild, Paris 1962 Patent granted for lipoic acid 1965- Member of National Academy of Sciences 1968 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow 1972-76 Member Levis Faculty Center Board of Directors 1977-78 Research sabbatical, Institut Edmund de Rothchild, Paris 1973-75 President of Levis Faculty Center Board of Directors 1978-81 Chairman of National Academy of Sciences, Section of Biochemistry 1982- Professor of Biochemistry, Emeritus, University of Illinois 1984 Honorary Doctorate, Indiana University 15/5/40 2 Box Contents List Box Contents Box Number Biographical and Personal Biographical Materials, 1967-1995 1 Personal Finances, 1961-65 1-2 Publications, Studies and Reports Journals and Reports, 1955-68 -

Maxine F. Singer Date of Birth 15 February 1931 Place New York, NY (USA) Nomination 9 June 1986 Field Biochemistry Title Professor

Maxine F. Singer Date of Birth 15 February 1931 Place New York, NY (USA) Nomination 9 June 1986 Field Biochemistry Title Professor Most important awards, prizes and academies Awards: US Government Senior Executive Service Outstanding Performance Award; National Medal of Science (1992); Vanneva-Bush Award (1999); National Academy of Science, USA; American Academy of Arts and Sciences; Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences; American Philosophical Society; Public Welfare Medal (2007). Academies: American Society of Biological Chemists; American Association for the Advancement of Science; American Chemical Society; American Society of Microbiologists; American Society for Cell Biology; Pontifical Academy of Sciences. Honorary Degrees: Swarthmore College; Wesleyan University; Harvard University; Yale University. Summary of scientific research Maxine Singer received the Ph.D. degree in Biochemistry in 1957 from Yale University. Her interest in nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) began during her post-doctoral work in Leon Heppel's laboratory at the National Institute of Health. Until 1975, she was a Research Biochemist in the Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, NIH. During that period she worked on the synthesis and structure of RNA and applied this experience to the work that elucidated the genetic code. She described and studied enzymes that degraded RNA in bacteria. By 1970 she became interested in animal viruses and took a sabbatical leave in the laboratory of Ernest Winocour (1971-2) at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. There she began work on aspects of simian virus 40. Moving to the National Cancer Institute in 1975, she con tinued this work studying defective SV40 viruses whose genomes contain regions of DNA from the host monkey cells. -

Spontaneous Tandem Genetic Duplications in Salmonella

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 78, No. 5, pp. 3113-3117, May 1981 Genetics Spontaneous tandem genetic duplications in Salmonella typhimurium arise by unequal recombination between rRNA (rrn) cistrons (gene duplication/chromosomal merodiploidy/transposon) PHILIP ANDERSON* AND JOHN ROTH Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 Communicated by Sydney Brenner, January 19, 1981 ABSTRACT A method is described to detect and measure the quences cause duplications to arise frequently in this region of frequency of spontaneous tandem genetic duplications located the chromosome. A preliminary account of this work has ap- throughout the Salmonella genome. The method is based on the peared elsewhere (3). ability of duplication-containing strains to inherit two selectable alleles of a single gene during generalized transductional crosses. MATERIALS AND METHODS One allele of the gene carries an insertion of the translocatable Media and Growth Conditions. The details of media, sup- tetracycline-resistance element TnlO; the other allele is a wild- plements, and growth conditions have been-described (4). Tet- type copy of that gene. Using this technique, we have measured racycline and kanamycin were added at 10 pug/ml and 50 ug/ the frequency oftandem duplications at 38 chromosomal sites and ml, respectively. the amount of material included in 199 independent duplications. Bacterial Strains. All strains are derivatives of Salmonella These results suggest that, in one region of the chromosome, tan- typhimurium strain LT2. A nonlysogenizing derivative of the dem duplications are particularly frequent events. Such duplica- high-transducing phage ofSchmieger (5), P22 HT105/1 int-201, tions have end points within rRNA (rrn) cistrons and probably was used in all transductions.