8 on Secret Marriages and Polygamy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Muslim Family Laws in Arab States AUP-ISIM-IS-BW-Welchman-22:BW 24-04-2007 19:22 Pagina 2

Women and Muslim Family Laws in Arab States: A Comparative Overview of WOMEN AND MUSLIM FAMILY LAWS WOMEN AND MUSLIM FAMILY LAWS Textual Development and Advocacy combines an examination of women’s rights in Muslim family law in Arab states across the Middle East with IN ARAB STATES discussions of the public debates surrounding the issues that are raised in processes of codification and amendment. A number of states have A COMPARATIVE OVERVIEW OF TEXTUAL recently either codified Muslim family law, or Women and Muslim Family Laws in have issued significant amendments or new DEVELOPMENT AND ADVOCACY Arab States: A Comparative Overview laws on the subject. This study considers these of Textual Development and new laws along with older statutes to comment Advocacy combines an examination. on patterns and dynamics of change both in Lynn Welchman the texts of the laws, and in the processes by women’s rights in Muslim family which they are drafted and issued. It draws IN ARAB STATES law in Arab states across the Middle on original legal texts as well as on extensive East with discussions of the public secondary literature for an insight into practice; debates surrounding interventions by women’s rights organisations and other parties are drawn on to identify women’s rights in Muslim family areas of the laws that remain contested. The law in Arab states across the Middle discussions are set in the contemporary global East with discussions of the public context that ‘internationalises’ the domestic debates the issues that are raised. and regional discussions. ISIM SERIES ON CONTEMPORARY LYNN WELCHMAN MUSLIMISIM SERIES SOCIETIES ON CONTEMPORARY MUSLIM SOCIETIES Lynn Welchmann is senior lecturer ISBN-13 978 90 5356 974 0 in Islamic and Middle Eastern Laws, School of Law at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) at the University of London. -

Common Law Marriage, Zawag Orfi and Zawaj Misyar

4 Journal of Law & Social Research (JLSR) Vol.1, No. 1 ‘Urf’ And Custom In Common Law And Islamic Law: Common Law Marriage, Zawag Orfi And Zawaj Misyar Muhammad Khalid Masud1 Islamic legal tradition is discursive; it developed through discourses at two levels, one between jurists and society, and the other between jurists and state. The part played by differences of opinion (Ikhtilaf) and juristic reasoning (Ijtihad) cannot be overstressed. It provided strong basis for legal pluralism and accommodation of social practices, especially in the area of marriage and divorce. State efforts to centralize law did not meet the approval of the jurists. Since state had no direct role in the development of fiqh, the systematization of Fiqh and Law Schools was achieved through consensus. Looking back at the history of Islamic law, we find that local practices in various cities like Medina and Kufa generated diverse legal doctrines and gradually produced more than nineteen schools of law (madhhab); about seven are still in practice today. The distinct mark of the development of fiqh in this period is the diversity of views among the jurists on almost each and every doctrine. This diversity was welcomed by Islamic legal theory as a valid manifestation of Ijtihad. It is typically usual in the Fiqh texts to mention more than one view on almost every point. This is evident even in Fiqh texts like Fatawa Alamgiri, which were designed as a guide book for the qadis. Instead of giving just one doctrine of law, these texts refer to different opinions. It looks strange, but the underlying concept seems to be that it was not for the jurist, to choose between these varying opinions. -

Part III Shari'a, Family Law, and Activism

Badran.211-232:Layout 1 12/6/10 3:44 PM Page 211 Part III Shari‘a, Family Law, and Activism Badran.211-232:Layout 1 12/6/10 3:44 PM Page 212 Badran.211-232:Layout 1 12/6/10 3:44 PM Page 213 Chapter 9 Women and Men Put Islamic Law to Their Own Use: Monogamy versus Secret Marriage in Mauritania Corinne Fortier In recent years, several Muslim countries have instituted significant leg- islative reforms, especially with respect to marriage and divorce. In Mauri- tania, the government introduced the first personal status code in 2001. This code recognizes women’s right to monogamy. But this code has not brought about a sociojuridical revolution, because these rights have long been rec- ognized and enforced in the Moorish society of Mauritania.1 They are ju- ridically and religiously legitimized in the classic Maliki legal texts that govern Moorish juridical practice. The right to monogamy is found in the classical texts of Islamic law (shari‘a), which form the legal basis of this society. Moorish women did not wait for the introduction of a personal status code that guaranteed their right to monogamy. The situation of Moorish women in this regard is different from that of Moroccan women, who in 2004 gained the right to monogamy through the reform of the family code, the Mudawana, which permits a woman to add a clause to her marriage con- tract giving her the right to divorce if her husband takes another wife. Un- 213 Badran.211-232:Layout 1 12/6/10 3:44 PM Page 214 214 CORINNE FORTIER like women elsewhere in Africa and the Middle East, Moorish women in Mauritania have traditionally contracted monogamous marriages. -

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Women and Misyar Marriage: Evolution and Progress in the Arabian Gulf Tofol Jassim Al-Nasr

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 12 Issue 3 Arab Women and Their Struggles for Socio- Article 4 economic and Political Rights Mar-2011 Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Women and Misyar Marriage: Evolution and Progress in the Arabian Gulf Tofol Jassim Al-Nasr Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Al-Nasr, Tofol Jassim (2011). Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Women and Misyar Marriage: Evolution and Progress in the Arabian Gulf. Journal of International Women's Studies, 12(3), 43-57. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol12/iss3/4 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2011 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Women and Misyar Marriage: Evolution and Progress in the Arabian Gulf By Tofol Jassim Al-Nasr1 Abstract Women’s status continues to undergo rapid evolution in the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC). The modernization policies sweeping the energy-rich region has resulted in unintended social and gender imbalances. Partly due to the wealth distribution policies and the vast influx of foreign labor into the GCC, the region’s indigenous people are facing several challenges as they adapt to their surrounding environment. Improvements to women’s education have resulted in an imbalance of highly educated women relative to their male counterparts in the region, tipping the scales of gender roles. -

Saudi Arabia

THEMATIC REPORT ON MUSLIM FAMILY LAW AND MUSLIM WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN SAUDI ARABIA 69th CEDAW Session Geneva, Switzerland February 2018 Musawah 15 Jalan Limau Purut, Bangsar Park, 59000 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Tel: +603 2083 0202 Fax: +603 2202 0303 Email: [email protected] Website: www.musawah.org TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………..……………………..3 B. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ..................................................................................................... 4 C. KEY ISSUES, LIVED REALITIES, ISLAMIC JURISPRUDENE AND REFORM ............. 8 1. The Male Guardianship System ...................................................................................... 8 2. Reciprocity of rights in marriage .................................................................................... 12 3. Women's consent and capacity to enter into marriage ................................................. 15 4. Early and child marriage ............................................................................................... 17 5. Polygamy ...................................................................................................................... 19 5. Divorce rights ............................................................................................................... 21 6. Custody and guardianship of children .......................................................................... 24 7. Violence against women ............................................................................................... 26 -

Temporary Marriage and Its Legality: Nikah-Al-Muta'h in Modern India

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 9 September 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 TEMPORARY MARRIAGE AND ITS LEGALITY: NIKAH-AL-MUTA’H IN MODERN INDIA. AUTHOR: ANAMYA SHARMA AMITY LAW SCHOOL, NOIDA (STUDENT) CO-AUTHOR – KSHITIJ PASRICHA AMITY LAW SCHOOL, NOIDA (STUDENT) Abstract For Hindus, marriages are for life and are of a pious and sacrament nature for the ultimate eternity. Unlike Hindus, where the marriage is a union of two individuals, marriages in Muslims are a social contract. The legal contract between a bride and bridegroom which results into a man and woman living together and supporting each other within the limits of what has been laid down in terms of rights and obligations. In Arabic dictionaries, mut’ah is defined as pleasure, enjoyment, and sexual desire. With a temporary nature, Mut’ah marriage has a pre-Islamic history to prevent men who stayed away for a long period of time from engaging in illicit relationship forbidden under Islam. In recent times, this practice is manipulated for personal enjoyment and desires. This paper has a detailed study on the problems related to temporary marriage / mut’ah marriage. Mut’ah marriage serves a hood for Prostitution, Human Trafficking and Forced marriages. The aim of such practice has been relinquished in the 21st century, but the practice is still followed in the old city of Hyderabad and Kerala, where NRI’s lure poor families to marry their daughters against a sum. This paper is a detailed study of status of women in Muslim society through the customary practice of mut’ah marriage. -

Mut'ah; a Comprehensive Guide

Mut'ah; a comprehensive guide Work file: mutah.pdf Project: Answering-Ansar.org Articles Revisions: No. Date Author Description Review Info Answering-Ansar.org Some revisionsَ 16.02.2008 2.0.1 2.0.0 05/12/2007 Answering-Ansar.org 2nd Edition 1.0.1 10.04.2004 Answering-Ansar.org Spelling corrections 1.0.0 22.11.2003 Answering-Ansar.org Created Copyright © 2002-2008 Answering-Ansar.org. • All Rights Reserved Page 2 of 251 Contents Table of Contents 1.T HE MARRIAGE OF MUT'AH ............................................................................................. 4 2.WH AT IS MUT'AH? ................................................................................................................ 6 3.T HE NECESSITY OF MUT'AH ............................................................................................. 8 4.Q UR'ANIC EVIDENCES FOR THE LEGITIMACY OF MUT'AH ................................ 14 5.C HAPTER 5: THE ARGUMENT THAT MUT'AH IS IMMORAL -I ............................. 43 6.C HAPTER 6: THE ARGUMENT THAT MUT'AH IS IMMORAL- II ......................... 100 7.C HAPTER 7: EXAMPLES OF SUNNI MORALITY ....................................................... 129 8.C HAPTER 8: WAS MUT'AH ABROGATED BY THE QUR'AN? ................................ 148 9.C HAPTER 9: WAS MUT'AH ABROGATED BY THE SUNNAH? ............................... 159 10.C HAPTER 10: THE TRUTH: THAT 'UMAR BANNED MUT'AH ............................. 182 11.CHAPTER 11: THE MISUSE OF SHI'A HADEETHS TO DEMONSTRATE THE P ROHIBITION OF MUTAH ................................................................................................ -

Morocco: Marriage and Divorce – Legal and Cultural Aspects

Report Morocco: Marriage and divorce – legal and cultural aspects Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium Report Morocco: Marriage and divorce – legal and cultural aspects LANDINFO – 21 APRIL 2017 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2018 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

Contemporary Temporary Marriage: a Blog- Analysis of First-Hand Experiences Sammy Z

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 17 Jan-2019 Contemporary Temporary Marriage: A Blog- analysis of First-hand Experiences Sammy Z. Badran Brian Turnbull Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Badran, Sammy Z. and Turnbull, Brian (2019). Contemporary Temporary Marriage: A Blog-analysis of First-hand Experiences. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(2), 241-256. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss2/17 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Contemporary Temporary Marriage: A Blog-analysis of First-hand Experiences By Sammy Badran1 and Brian Turnbull2 Abstract Within Islam, a temporary marriage generally implies a short-term marriage between a man and a woman that does not come with a long-term commitment and may or may not have an explicit, pre-established timeline or endpoint. The partial religious legitimation of temporary marriage via Islamic fatwas has recently revived the institution. Some suggest that the rising popularity is an attempt by individuals to fulfill sexual desires within the confines of a religiously- legitimized institution; while others argue that it can lead to exploitation and perhaps slavery of women and girls. -

Women and Misyar Marriage: Evolution and Progress in the Arabian Gulf Tofol Jassim Al-Nasr

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 12 Issue 3 Arab Women and Their Struggles for Socio- Article 4 economic and Political Rights Mar-2011 Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Women and Misyar Marriage: Evolution and Progress in the Arabian Gulf Tofol Jassim Al-Nasr Recommended Citation Al-Nasr, Tofol Jassim (2011). Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Women and Misyar Marriage: Evolution and Progress in the Arabian Gulf. Journal of International Women's Studies, 12(3), 43-57. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol12/iss3/4 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2011 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Women and Misyar Marriage: Evolution and Progress in the Arabian Gulf By Tofol Jassim Al-Nasr1 Abstract Women’s status continues to undergo rapid evolution in the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC). The modernization policies sweeping the energy-rich region has resulted in unintended social and gender imbalances. Partly due to the wealth distribution policies and the vast influx of foreign labor into the GCC, the region’s indigenous people are facing several challenges as they adapt to their surrounding environment. -

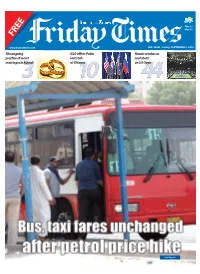

Raonic Crashes As Roof Shuts on US Open the Ongoing Practice Of

Min 33º Max 48º FREE www.kuwaittimes.net NO: 16981 - Friday, SEPTEMBER 2, 2016 The ongoing G20 offers Putin Raonic crashes as practice of secret last stab roof shuts marriages in3 Kuwait at Obama10 on US44 Open See Page 9 Local FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 2016 Local Spotlight PHOTO OF THE DAY Rent cheaters By Muna Al-Fuzai [email protected] ent cheating is a new form of deception in Kuwait. Today’s story is not new to me, as I Rhave heard about it many times before, except this seems to be the worst. When you fall victim to rent cheaters, you can end in jail, while they can take your money and sell your furniture too. Guess what? If you thought you can leave the country, you can’t, because your name will be on the travel ban list until you settle this matter. It is a pain that no one wishes to deal with, but some expats fall into this trap. My article today may end with an advice, but it is your choice not to trust or deal with rent cheaters. This letter is from a family that is confronting this nightmare now. They are facing a serious problem if no action is taken by them. Let me explain how this family fell a victim to a rent cheater. The family of four persons rented a flat in Salmiya four months ago. The haris told them the rent is KD 200 inclusive of water and electricity, plus KD 10 for himself (for cleaning) and KD 200 down payment, Rent was due by the 5th of every month. -

Medieval State and Society

M.A. HISTORY - II SEMESTER STUDY MATERIAL PAPER – 2.1 MEDIEVAL STATE AND SOCIETY UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION Prepared by: Dr.N.PADMANABHAN Reader, P.G.Department of History C.A.S.College, Madayi Dt.Kannur-Kerala. 2008 Admission MA HIS Pr 2. 1 (M.S & S) 405 UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION STUDY MATERIAL II SEMESTER M.A. HISTORY PAPER - 2. 1 MEDIEVAL STATE AND SOCIETY Prepared by: Dr. N.Padmanabhan Reader P.G.Department of History C.A.S.College, Madayi P.O.Payangadi-RS-670358 Dt.Kannur-Kerala. Type Setting & Layout: Computer Section, SDE. © Reserved 2 CHAPTERS CONTENTS PAGES I TRANSITION FROM ANCIENT TO MEDIEVAL II MEDIEVAL POLITICAL SYSTEM III AGRARIAN SOCIETY 1V MEDIEVAL TRADE V MEDIEVAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY V1 RELIGION AND IDEOLOGY V11 TRANSITION FROM MEDIEVAL TO MODERN 3 CHAPTER- I TRANSITION FROM ANCIENT TO MEDIEVAL For the sake of the convenience of study history has been divided into three – the ancient, medieval and modern periods.Of course we do not have any date or even a century to demarcate these periods.The concept of ancient, medieval and modern is amorphous.It varies according to regions. Still there are characteristic features of these epochs.The accepted demarcations of ancient, medieval and modern world is a Europo centric one.The fall of Western Roman empire in AD 476 is considered to be the end of ancient period and beginning of the middle ages.The eastern Roman empire continued to exist for about a thousand years more and the fall of the eastern Roman empire in 1453, following the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks is considered to be the end of the medieval period and the beginning of modern period.The general features of the transition from ancient to medieval world the decline of ancient empire decline of trade and urban centres, development of feudal land relations growth of regional kingdoms in the West, emergence of new empires in the Eastern, etc.