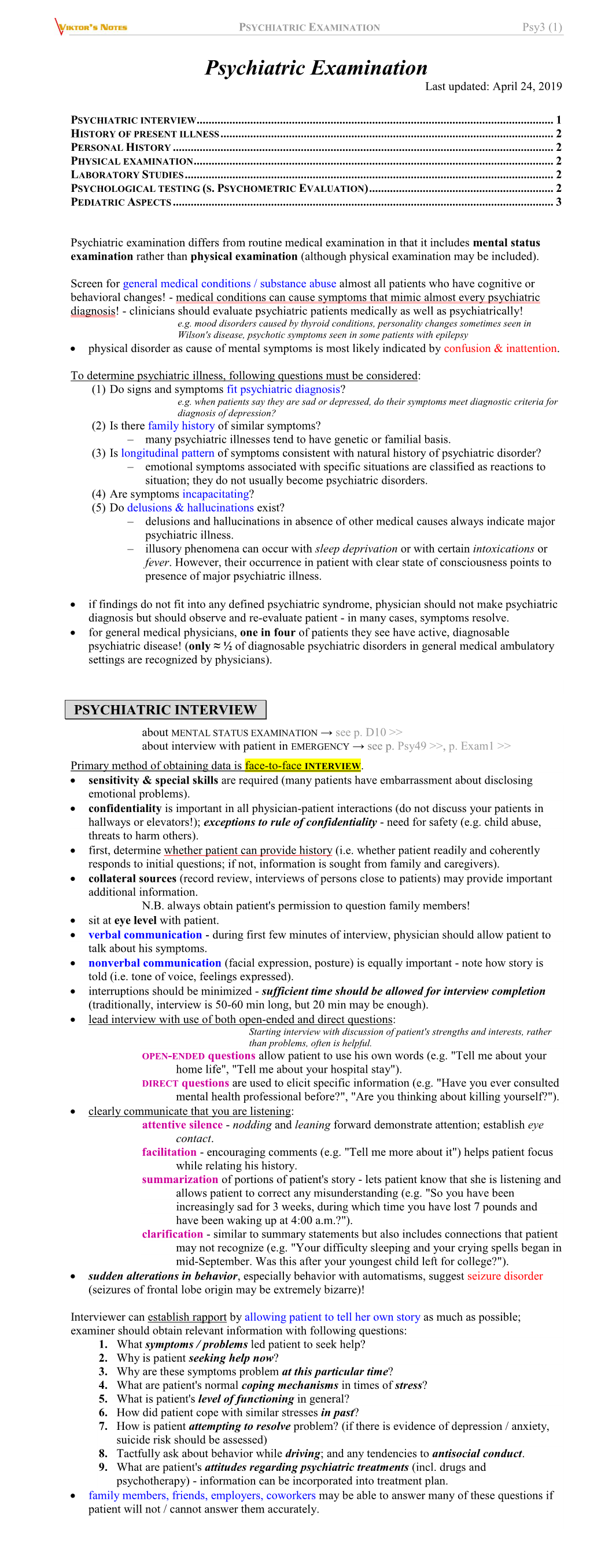

PSYCHIATRIC EXAMINATION Psy3 (1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dual Diagnosis Screening Interview to Identify Psychiatric Comorbidity in Substance Users: Development and Validation of a Brief Instrument

Research Report European Addiction Eur Addict Res 2014;20:41–48 Received: October 16, 2012 Research DOI: 10.1159/000351519 Accepted: April 15, 2013 Published online: August 1, 2013 Dual Diagnosis Screening Interview to Identify Psychiatric Comorbidity in Substance Users: Development and Validation of a Brief Instrument a a, b a, c, d Joan Ignasi Mestre-Pintó Antònia Domingo-Salvany Rocío Martín-Santos a, e, f Marta Torrens The PsyCoBarcelona Group (see Appendix) a b c Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM), CIBERESP, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital Clinic, IDIBAPS, d e f CIBERSAM, University of Barcelona, Institute of Neuropsychiatry and Addictions, Hospital del Mar, and Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona , Spain Key Words administration was 16.8 ± 2.5 min. Conclusion: The DDSI is a Psychopathology · Dual diagnosis · Screening · valid and easy-to-administer screening tool to detect possi- Dual Diagnosis Screening Instrument ble psychiatric comorbidity among substance users. Copyright © 2013 S. Karger AG, Basel Abstract Aim: The objective of this study was to develop and validate Introduction a brief tool, the Dual Diagnosis Screening Instrument (DDSI), to screen psychiatric disorders in substance users in treat- To identify psychiatric comorbidity among individu- ment and nontreatment-seeking samples. Methods: A total als with substance use disorders (SUDs) is an area of of 827 substance users (66.5% male, mean age 28.6 ± 9.9 great clinical and public health interest. Drug users with years) recruited in treatment (in- and outpatient) and non- other psychiatric comorbid disorders have more emer- treatment (substance user volunteers in university research gency admissions, higher prevalence of suicide, medical studies) settings were assessed by trained interviewers using conditions (e.g. -

Factors Associated with the Onset of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Living in 12 Different Countries

Epidemiology and Psychiatric Factors associated with the onset of major Sciences depressive disorder in adults with type 2 cambridge.org/eps diabetes living in 12 different countries: results from the INTERPRET-DD prospective study 1 2 3 4 5 6 Original Article C. E. Lloyd ,N.Sartorius,H.U.Ahmed,A.Alvarez,S.Bahendeka,A.E.Bobrov, L. Burti7,S.K.Chaturvedi8,W.Gaebel9,G.deGirolamo10,T.M.Gondek11, Cite this article: Lloyd CE et al (2020). Factors 12 13 14 15,16 17 18 associated with the onset of major depressive M. Guinzbourg ,M.G.Heinze ,A.Khan , A. Kiejna ,A.Kokoszka ,T.Kamala , disorder in adults with type 2 diabetes living in 12 19 20 21 22 23,24,25 different countries: results from the INTERPRET- N. M. Lalic ,D.Lecic-Tosevski ,E.Mannucci ,B.Mankovsky ,K.Müssig , DD prospective study. Epidemiology and V. Mutiso26,D.Ndetei27, A. Nouwen28,G.Rabbani29,S.S.Srikanta30,E.G.Starostina31, Psychiatric Sciences 29, e134, 1–9. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/S2045796020000438 M. Shevchuk22,R.Taj14,U.Valentini32,K.vanDam28,O.Vukovic33 and W. Wölwer9 Received: 21 January 2020 1The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK; 2Association for the Improvement of Mental Health Programmes, Geneva, Revised: 14 April 2020 3 Accepted: 19 April 2020 Switzerland; Child Adolescent & Family Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Dhaka, Bangladesh; 4Servicio de Endocrinologia y Medicina Nuclear del Hospital Italiano de Buenis Aires, Buenis Aires, Argentina; 5The Key words: Mother Kevin Post Graduate Medical School, Uganda Martyrs University, Kampala, Uganda; 6Federal -

Psychiatric Interview Externalizing Disorders

7/16/2013 Cognitive behavioral therapy Clinical hypnosis: level two Sheree Shafer FNP-BC, PMNCNS-BC, DNP ADOS (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) Child First (Forensic interview for child and adolescent sexual abuse) Dialectical behavioral therapy interventions Treatment for 700-800 patients per year (two NP’s) Research: increasing primary care nurse Comprehensive evaluation practitioner knowledge, comfort, and Facilitate referrals as needed Provide both pharmacotherapy and nonpharmacotherapy practice for pediatric patients with ADHD, Therapist for 0-5 population, liaison with BSU for children and mothers with post partum depression depression, and/ or anxiety disorders Grant for drug and alcohol therapist, specializes in Served as a CBT therapist and blind evaluator adolescent care (intake completed at our office within one week of referral) for a quasi experimental study measuring the Collaborating psychiatrist on site monthly MA dedicated to program effectiveness of 6-8 CBT sessions provided Formalized referral process within primary care versus treatment as usual Strong relationship with school psychologists Formalized process for communication with local school Program evaluation districts At the current rate of service utilization, approximately 12, 624 child and adolescent psychiatrists are needed. The number of available psychiatrists through 2020 is projected as 8,312 (AACAP, 2009). 1 7/16/2013 80% of children and adolescents respond to CONVENTIONAL MENTAL HEATH INTEGRATED MODEL OF CARE current evidence based treatment Call for phone discussion of need Call for discussion of need, Call back for an intake intake information completed interventions for ADHD ,anxiety, and Intake within 2 weeks Reviewed and call back within 48 depressive disorders (American Academy of Staffing within 2 weeks hours Assignment within 2 weeks Diagnostic and treatment Children and Adolescent Psychiary,2007; Psychiatric evaluation may be evaluation within 2 weeks. -

The Psychiatric Interview Clinical Interviewing Is the Single Most Important Skill Required in Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Interview Clinical interviewing is the single most important skill required in psychiatry. The interview constitutes the principal means for gaining an understanding of a patient’s difficulties. This understanding leads to a diagnostic formulation and the development of treatment plan. The interview is as important to psychiatry as the operating room is to surgery and the laboratory is to internal medicine. The assessment process in psychiatry relies primarily on the interviewing and observational skills of practitioners because there is no laboratory test, tissue diagnosis or imaging method available to confirm a psychiatric diagnosis. The interview can be defined as “the skill of encouraging disclosure of personal information for a specific professional purpose” (McCready, 1986), and serves a variety of functions: • Collecting clinical information in an efficient manner • Eliciting emotions, feelings, and attitudes • Establishing a doctor-patient relationship and developing rapport • Generating and testing a set of hypotheses to arrive at a preferred diagnosis, accompanied by a list of other conditions (called a differential diagnosis) which must be considered • Determining areas for further investigation • Developing a treatment plan Interviewing is not simply the task of taking a history. Rather, it is the process of determining which illness the patient has, and understanding how he or she has been affected by it. Far more than a series of questions, a well-conducted interview yields nformationi that helps develop an individualized approach for treating the patient. While providing treatment is not usually identified as an explicit aim of initial interviews, it often is a component. Pekarik (1993) and Talmon (1990) reported that a single meeting gave a number of patients enough relief from their stressors that follow-up was not required. -

Treating Substance Abuse Is Not Enough: Comorbidities in Consecutively Admitted Female Prisoners

Addictive Behaviors 46 (2015) 25–30 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Addictive Behaviors Treating substance abuse is not enough: Comorbidities in consecutively admitted female prisoners Jan Mir a, Sinja Kastner a, Stefan Priebe b, Norbert Konrad c, Andreas Ströhle a,AdrianP.Mundtb,d,⁎ a Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Charité Campus Mitte, Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany b Unit for Social and Community Psychiatry (WHO Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Services Development), Queen Mary University of London, UK c Institute of Forensic Psychiatry, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany d Escuela de Medicina sede Puerto Montt, Universidad San Sebastián, Chile HIGHLIGHTS • A majority of 62% of females have substance use disorders at admission to prison. • Opiates are the most frequent substances of addiction in 35% of this population. • Addictions are highly comorbid with affective, personality and anxiety disorders. • Comorbidities do not differ between subgroups addicted to different substances. • Interventions should be generic, robust and flexible to cover different disorders. article info abstract Available online 21 February 2015 Introduction: Several studies have pointed to high rates of substance use disorders among female prisoners. The present study aimed to assess comorbidities of substance use disorders with other mental disorders in female Keywords: prisoners at admission to a penal justice system. Substance use disorders Methods: A sample of 150 female prisoners, consecutively admitted to the penal justice system of Berlin, Comorbidity Germany, was interviewed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). The presence of bor- Mental disorders derline personality disorder was assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview II for DSM-IV. Prevalence rates Female prison population fi Prevalence rates and comorbidities were calculated as percentage values and 95% con dence intervals (CIs). -

Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults Second Edition

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults Second Edition 1 WORK GROUP ON PSYCHIATRIC EVALUATION Michael J. Vergare, M.D., Chair Renée L. Binder, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Marc Galanter, M.D. Francis G. Lu, M.D. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Sherwyn M. Woods, M.D., Ph.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. Joel Yager, M.D. AREA AND COMPONENT LIAISONS Robert Pyles, M.D. (Area I) C. Deborah Cross, M.D. (Area II) Roger Peele, M.D. (Area III) Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. (Area IV) John P. D. Shemo, M.D. (Area V) Lawrence Lurie, M.D. (Area VI) R. Dale Walker, M.D. (Area VII) Mary Ann Barnovitz, M.D. Sheila Hafter Gray, M.D. Sunil Saxena, M.D. Tina Tonnu, M.D. STAFF Robert Kunkle, M.A., Senior Program Manager Amy B. Albert, B.A., Assistant Project Manager Laura J. Fochtmann, M.D., Medical Editor Claudia Hart, Director, Department of Quality Improvement and Psychiatric Services Darrel A. Regier, M.D., M.P.H., Director, Division of Research This practice guideline was approved in December 2005 and published in June 2006. 2 APA Practice Guidelines CONTENTS Statement of Intent. Development Process . Introduction . I. Purpose of Evaluation. A. General Psychiatric Evaluation . B. Emergency Evaluation . C. Clinical Consultation. D. Other Consultations . II. Site of the Clinical Evaluation . -

{FREE} the Psychiatric Interview Kindle

THE PSYCHIATRIC INTERVIEW PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Daniel J. Carlat | 348 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Lippincott Williams and Wilkins | 9781496327710 | English | Philadelphia, United States The Psychiatric Interview | SIMPLY PSYCH EDU Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Helen Swick Perry Editor ,. Otto Allen Will Introduction. This is a book for all those working in the field of psychiatric disorder. It will be invaluable to medical students and doctors training in general practice, emergency medicine and psychiatry. At a time when the assessment of psychiatric patients is the responsibility of a range of clinicians, The Psychiatric Interview will also be of assistance to clinical psychologists, This is a book for all those working in the field of psychiatric disorder. At a time when the assessment of psychiatric patients is the responsibility of a range of clinicians, The Psychiatric Interview will also be of assistance to clinical psychologists, social workers and psychiatric nurses. It will also have a place as a reference book for police and security officers. Get A Copy. Paperback , pages. Published February 17th by W. Norton Company first published February More Details Original Title. Other Editions 2. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about The Psychiatric Interview , please sign up. Be the first to ask a question about The Psychiatric Interview. Lists with This Book. -

History Taking and Mental State Examination (Mse)

HISTORY TAKING AND MENTAL STATE EXAMINATION (MSE) Dr. Ali Bahathig, FRCPC, Assistant Professor and Consultant of Psychiatry & Psychosomatic Medicine Psychosomatic Unit, Psychiatry Department King Saud University Medical City (KSUMC) 1440/1441 2019/2020 SPECIAL TAHNKS TO: 1. Dr. Fahad Alosaimi, MD, Professor and Consultant of Psychiatry & Psychosomatic medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University 2. Dr. Ahmad Alhadi, MD, Associate Professor and Consultant of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, College of Medicine, King Saud University 3. Dr. Mohammed Al-Sughayir, MD, Professor and Consultant of Psychiatry, College of medicine, King Saud University Objectives: ➢ To describe History taking in psychiatry. ➢ To see how to take Psychiatric History. ➢ To describe MSE component. ➢ To see how to do MSE. Introduction: ➢ One supreme skill of any physician is active listening. ➢ Physicians should monitor : ➢ The Content: of the interaction (what patient and doctor say to each other) ➢ The Process: (what patient and doctor may not say but clearly convey in many other ways). ➢ Physicians should be sensitive to the effects of patient history/background, culture, environment, and psychology on the doctor–patient relationship ➢ Because patients are multifaceted people. ➢ Physician should not consider disease/syndromes only. The teacher– student (or parent– The mutual child, guidance– participation cooperation) model. model. The friendship (or The active-passive socially intimate) model Models of model. the doctor– patient relationship include: Introduction: ➢ The more that doctors understand themselves, the more secure they feel, and the better able they are to modify destructive attitudes. ➢ Increased flexibility leads to a responsiveness to the subtle interplay between doctor and patient and also assumes a certain tolerance for the uncertainty present in any clinical situation with any patient. -

History Taking & Risk Assessment & Mental State Examination Resource

History Taking & Risk Assessment & Mental State Examination Resource Pack for use with videos Dr Sian Hughes Academic Unit of Psychiatry Oakfield House, Oakfield Grove, Bristol BS8 2BN Tel: (0117) 331410, Fax (0117) 3314026 Resource Pack Contents 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Main Menus of the videos 4 2. History Taking & Risk Assessment 6 2.1 Presenting Complaint & HPC 7 2.2 Past Psychiatric History 7 2.3 Medication 8 2.4 Family History 8 2.5 Personal History 10 2.6 Premorbid Personality 11 2.7 Difficult Questions, Difficult Patients 12 2.8 Risk Assessment 13 2.9 Further Study 14 3. Mental State Examination 15 3.1 Appearance & Behaviour 16 3.2 Speech 17 3.3 Mood 18 3.4 Thought 19 3.5 Perceptions 21 3.5 Delusions 22 3.6 Cognition 23 3.7 Insight 24 4. Appendices 4.1 Depression: criteria from DSM-IV and ICD-10 25 4.2 Mrs. Jackson: extracts from the old notes 26 4.3. Mrs. Down: transcript of notes 28 4.4 The Folstein MMSE 32 4.5 Cognitive State Examination 34 5. Bibliography 37 2 i.Introduction Introduction History taking, risk assessment and the mental state examination are core clinical skills. They are best learned by practice and repetition, and we recommend that you see as many patients as possible in order to enhance your skills. The purpose of the videos and this accompanying resource pack is to give you a starting point to work from as you learn to take a psychiatric history and do a mental state examination. -

Recommended Texts / Useful Resources for Psychiatry Trainees

Recommended Texts / Useful Resources for Psychiatry Trainees: Context: The following recommendations are aimed to assist trainees to prepare for the RANZCP Fellowship Program examinations, particularly the Written Examinations. The trainees are required to have in-depth and comprehensive knowledge of the curriculum, with a reminder that in addition to core clinical psychiatry, they need to cover many areas including phenomenology, epidemiology, relevant neurology and brain diseases, addictions, history of psychiatry, research in psychiatry and evidence base, drug prescribing, ethics, medico-legal concepts and professionalism. The level to target in preparation is that of a competent junior consultant. A junior consultant needs in-depth Specialist knowledge to be able to act independently and safely, working with a broad overview of the related and significant issues. The following texts are not listed in order of priority, but rather in groups covering general and focused areas of knowledge. The list has been prepared in consultation with a number of Directors of Training and psychiatrists involved in current registrar training and exams. Trainees need to have studied in detail a number of the texts over the various areas/ fields of knowledge to be prepared for the junior consultant standard of the written exams. Supervisors, senior trainees and mentors may recommend their preferred texts. It is suggested that trainees source the most recent editions – some current ones are listed here. This list represents basic requirements. It is not -

Neurosurgery & Psychiatry

Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1994;57:1161-1164 1 161 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.57.10.1161 on 1 October 1994. Downloaded from Journa of NEUROLOGY NEUROSURGERY & PSYCHIATRY Editorial Somatisation in neurological practice The diagnosis chronic disorder with onset before the age of 30 and The average British neurologist, according to a recent multiple symptoms pertaining to various systems-is also survey,' will fail to find an adequate physiological expla- included here. nation for the symptoms of one in every five of his or her Within the wider concept of somatisation, hysteria, or patients despite appropriate, often exhaustive, investiga- conversion disorder, if narrowly defined, refers to those tions. In some patients organic pathology may be pre- unexplained symptoms suggestive of neurological disease sent, but the symptoms and the ensuing disability cannot (loss of function or sensation) and has the doubtful dis- be satisfactorily explained as a result. According to Mace tinction among psychiatric diagnoses of still invoking and Trimble,' the authors of the survey, as many as "Freudian" mechanisms as an explanation. The idea that 36 000 such patients may be seen by British neurologists a traumatic experience, usually of a sexual nature, could every year. Surveys of neurological inpatients have be rendered innocuous by being transformed into a produced equally striking results. In a recent study of 100 somatic symptom5 is central to the diagnosis. The resolu- consecutive new admissions to a neurological ward an tion of this unconscious conflict is the primary gain and adequate organic explanation for the symptoms was only the advantages resulting from the assumption of the sick forthcoming in 40 of them, whereas in the rest organic role are known as the secondary gain. -

Prevalence and Predictors of Substance-Related Emergency

Research Article 2016 iMedPub Journals Dual Diagnosis: Open Access http://www.imedpub.com/ ISSN 2472-5048 Vol. 1 No. 1:4 DOI: 10.21767/2472-5048.100004 Prevalence and Predictors of Substance- M Scott Young and Related Emergency Psychiatry Admissions Kathleen A Moore Department of Mental Health Law and Policy, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida, USA Abstract Background: Individuals commonly present for emergency psychiatry services Corresponding author: M Scott Young for reasons related to their use of alcohol or illicit drugs. This study assessed the prevalence of these phenomena and explored characteristics distinguishing emergency psychiatry admissions with versus without presenting problems related to substance use. [email protected] Methods: Data included standardized emergency psychiatry intake interviews from 2,161 consecutive admissions to three hospital-based emergency psychiatry Department of Mental Health Law and departments in Florida’s Tampa Bay area. Admissions were classified as substance- Policy, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental involved if substance use was ascertained to be related to the presenting Health Institute, University of South Florida, problem(s). Cases with only substance-related presenting problems were classified USA. as substance-only admissions. Descriptive statistics compared substance-involved admissions to those whose presenting problems were not related to substance Tel: 813-974-8734 use. A logistic regression determined the characteristics most predictive of substance-involved admissions; similarly, a second logistic regression analysis was used to predict substance-only admissions. Findings: A substantial number of emergency psychiatry admissions (n=507; 23.5%) Citation: Young MS, Moore KA. Prevalence were identified as being substance-involved.