'The Mining Company of Ireland And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thurles MD May 2021 Meeting Minutes.Pdf

Comhairle Contac Thiobraid Arann Comhsirlo Conlso Trppgrary Count) Counail r 0761 06 5000 Tiuperary County eouncil Thiobraid Arann, Thuflet 0 cuStomsrioNrc€ 0iligi Choantar Ssrdasech hluniriprl 0ntlct 0ifice. (0trp0omrycoco.ic c an C.rstlo Avsnue, 0hurlni s, Ascaill an Thurhs. tipprorycoco.io Chaislod in, 0urla s, Cc. [:pperlrl 00. Ihiobraid Arano MINUTES OF THE MAY MONTHLY MEETING OF THE THURLES MUNICIPAL DISTRICT WHICH WAS HELD REMOTELY VIA ZOOM ON 17TH MAY 2O2'. Present Councillor Noel Coonan Cathaoirleach, presided. Councillors Seamus Hanafin, Shane Lee, Mich6al Lowry, Eddie Moran, Jim Ryan, Peter Ryan, Sean Ryan and Michael Smith Also Present: Eamon Lonergan A/District Director Liam Brett, Senior Engineer Thomas Duffy District Engineer Jim Ryan Executive Engineer Sharon Scully District Ad min istrator Orla McDonnell Acting Senior Staff Officer 1. Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest, There were no Disclosures/conflicts of Interest raised at the Meeting. 2. Adootion of Minutes. It was proposed by councillor S, Hanafin and seconded by councillor s Ryan and resolved: "That the Minutes of the April 202L Monthly Meeting which was held on the 19th April 2021 be adopted as a true record of the business transacted at the Meeting," 3. Update from Planning Section Nuala o'connell, senior Planner and Kieran Ladden, senior Executive Engineer were in attendance via Zoom for this item, A Planning Briefing Note was circulated to the Members with the Agenda in advance of the Meeting. The report outlined the following:- o New Policy /Strategic Issues . NPF: Urban Regeneration and Development Fund Plaza a, Comhsirlo Contao Trppgrary County Council, t 0i6l 0$ 5000 Comhaiile Contao Thlobraid Arann Ihiobraid irann. -

Tipperary News Part 6

Clonmel Advertiser. 20-4-1822 We regret having to mention a cruel and barbarous murder, attended with circumstances of great audacity, that has taken place on the borders of Tipperary and Kilkenny. A farmer of the name of Morris, at Killemry, near Nine-Mile-House, having become obnoxious to the public disturbers, received a threatening notice some short time back, he having lately come to reside there. On Wednesday night last a cow of his was driven into the bog, where she perished; on Thursday morning he sent two servants, a male and female, to the bog, the male servant to skin the cow and the female to assist him; but while the woman went for a pail of water, three ruffians came, and each of them discharged their arms at him, and lodged several balls and slugs in his body, and then went off. This occurred about midday. No one dared to interfere, either for the prevention of this crime, or to follow in pursuit of the murderers. The sufferer was quite a youth, and had committed no offence, even against the banditti, but that of doing his master’s business. Clonmel Advertiser 24-8-1835 Last Saturday, being the fair day at Carrick-on-Suir, and also a holiday in the Roman Catholic Church, an immense assemblage of the peasantry poured into the town at an early hour from all directions of the surrounding country. The show of cattle was was by no means inferior-but the only disposable commodity , for which a brisk demand appeared evidently conspicuous, was for Feehans brown stout. -

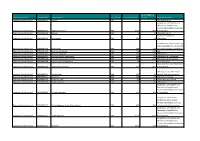

Organisation Name Scheme Code Scheme Name Supply Type Population Served Volume Supplied (M3/Day) Type of Treatment Tipperary

Volume Supplied Organisation Name Scheme Code Scheme Name Supply Type Population Served (m3/day) Type Of Treatment Tipperary County Council 2900PUB0101 Ahenny PWS 77 29 Chlorination & UV Coagulation, clarification and Flocculation, Rapid Gravity filtration followed by Chlorination Tipperary County Council 2900PUB0102 Ardfinnan Regional PWS 11256 4878 & Fluoridation Tipperary County Council 2900PUB0104 Ballinvir PWS 30 85 Chlorination & UV Aeration, Chlorination, Tipperary County Council 2800PUB1002 Borrisokane PWS 1841 749 Fluoridation Disinfection by Chlorination using sodium hypochlorite. Alarmed on- Tipperary County Council 2800PUB1016 Borrisoleigh PWS 2395 336 line residual chlorine monitoring. Tipperary County Council 3700PUB1040 Burncourt Ballylooby PWS 1749 1020 N/A Tipperary County Council 2900PUB0105 Burncourt Regional PWS 1817 1291 Chlorination Tipperary County Council 2900PUB0107 Carrick-On-Suir (Crottys Lake) PWS 2091 625 Chlorination & Fluoridation Tipperary County Council 2900PUB0108 Carrick-On-Suir (Lingaun River) PWS 3922 1172 Chlorination & Fluoridation Tipperary County Council 3700PUB1038 Castlecranna, Carrigatogher PWS 66 9 UV, Chlorination Slow Sand Filtration, Chlorination Tipperary County Council 2900PUB0109 Clonmel Poulavanogue PWS 2711 1875 & Fluoridation Chlorination, alarmed on-line Tipperary County Council 2800PUB1005 Cloughjordan PWS 1143 506 residual chlorine monitoring. Tipperary County Council 2900PUB0111 Coalbrook PWS 1566 877 Chlorine\Iron+Mang Tipperary County Council 2900PUB0112 Commons PWS PWS 471 212 -

MINUTES OCTOBER 2020 DISTRICT MEETING.Pdf

MINUTES OF THE OCTOBER MONTHLY MEETING OF THE THURLES MUNICIPAL DISTRICT WHICH WAS HELD IN THE TIPPERARY COUNTY COUNCIL DISTRICT OFFICES, CASTLE AVENUE, THURLES ON 19th OCTOBER, 2020 Present: Councillor Noel Coonan Cathaoirleach, presided. Councillors Seamus Hanafin, Shane Lee, Michéal Lowry, Jim Ryan, Peter Ryan, Sean Ryan and Michael Smith. Also Present: Eamonn Lonergan Acting District Director Thomas Duffy District Engineer Janice Gardiner Acting Meetings Administrator Orla McDonnell Staff Officer. Apologies: Cllr. Eddie Moran 1. Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest. There were no Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest raised at the Meeting. 2. Adoption of Minutes. It was proposed by Councillor. S. Ryan and seconded by Councillor S. Lee and resolved: "That the Minutes of the September Monthly Meeting which was held on the 21st September 2020 be adopted as a true record of the business transacted at the Meeting." 3. Thurles Municipal District – Draft Budgetary Plan 2021. Mr. Liam McCarthy, Director of Services introduced Ms. Noreen O’Dwyer who has been appointed as Acting Financial Management Accountant. Copy of the Thurles Municipal District Draft Budgetary Plan 2021 was circulated by email on 8th October, giving the required 7 days notice, and was also circulated with the Agenda in accordance with Section 102(4A)(b) of the Local Government Act, 2001. Mr. McCarthy outlined the Thurles Municipal District Draft Budgetary Plan for 2021 to the Members and highlighted the following:- • The GMA sets out the discretionary funding that is allocated to each Municipal District. 19th. October 2020 • The GMA does not replace the main strategic, non discretionary expenditure of the Council. The total provisional allocation for the General Municipal Allocation for 2021 is €952,530 comprising €602,530 (arising from the decision to increase the Local Property Tax at the September Meeting and allocate 50% of the increase to the GMA) and €350,000 of an allocation similar to last year. -

Corporate Plan Contents 1

2015-2019 CORPORATE PLAN CONTENTS 1. WELCOME Foreword by Cathaoirleach - Michael FitzGerald 4 Foreword by Chief Executive - Joe MacGrath 5 2. ABOUT THE CORPORATE PLAN 2.1 What is the Corporate Plan? 7 2.2 Context of the Plan 8 2.3 Vision Statement 10 2.4 How Do We Work 12 3. VISION FOR TIPPERARY COUNTY COUNCIL 3.1 Strong Economy 16 3.2 Quality of Life 18 3.3 Quality Environment 20 4. MONITORING & IMPLEMENTATION 22 APPENDICES Appendix 1: List of Elected Councillors by Municipal District 24 Appendix 2: List of Strategic Policy Committees & members 28 Appendix 3: Political & Management Organisational Structure 30 Appendix 4: Achievements 32 Page 4 Tipperary County Council • Corporate Plan 2015-2019 Foreword - Cathaoirleach Foreword - Chief Executive A significant The downturn in the economy This Corporate Plan The objectives of the Corporate Plan presented us with significant will be delivered by the Cathaoirleach milestone in the challenges, and the new council has serves as Tipperary and Councillors in conjunction with the adapted accordingly by reducing our Council’s staff and we will utilise all our history of Local cost base, becoming more efficient County Council’s resources to develop Tipperary as an Government in County and positioning Tipperary as ‘open for Strategic framework excellent place to live, work and invest. business’ as we return to economic Tipperary was marked vitality. There is therefore, a new for action during the We seek to produce a written in June 2014 when challenge to identify and support lifetime of this Council statement on what objectives we ideas and opportunities, to remain aim to achieve over the period of 10 local authorities as an outward looking county while and will act as the the plan, the supporting strategies maintaining our ability to be responsive adopted to achieve these aims and in Tipperary were to the needs of the people we serve. -

Settlement Nodes

Settlement Nodes 89 90 AHENNY Context Ahenny is identified in the County Development Plan as a Settlement Node. This settlement is located in the eastern part of the county in close proximity to the Kilkenny border. Infrastructure Water Supply: There is currently an adequate water supply in Ahenny Waste Water: There is currently no wastewater treatment system in Ahenny Development Objectives DO1 The Council will seek to protect views from the village centre towards the surrounding uplands. DO2 The Council will seek the retention of existing stone buildings and stonewalls as part of new development. DO3 As opportunities arise the Council will seek the enhancement of the visual amenities of the village and the provision of a village centre focal point. DO4 The Council will seek to improve the carriageway and junction definition in order to facilitate the appropriate expansion of the village. DO5 Where development is proposed on residentially zoned lands, the following criteria should be met: (i) Vehicular access shell be to the public road along the eastern site boundary; (ii) Dwellings shall be constructed on the lower contours of the site and the elevated western part of the site retained for amenity use; (iii) Dwelling units shall be designed so as to enhance the character of the neighbouring Architectural Conservation Area. 91 ARDMAYLE Context Ardmayle is located in the north of the County and is identified as a Settlement Node in the County Development Plan. Infrastructure Water Supply: There is currently adequate water supply in Ardmayle Waste Water: Currently there is no wastewater treatment system in Ardmayle Development Objectives New development in Ardmayle shall respect the nature and scale of the village and shall adhere to the following specific objectives; DO1 As opportunities arise the Council will seek the enhancement of the visual amenities of the village and the provision of a village centre focal point. -

Tipperary South Riding

Recorded Monuments Protected under Section ][2 of the National Monuments (Amendment) Act, 1994 Coun~F Tipperary South Riding D0chasThe JLteritage Service Departmentof Arts, Heritage, Gaettachtand the Islands 1997 RECORD OF MONUMENTSAND PLACES as Established under Section 12 of the National Monuments (Amendment)Act 1994 COUNTYTIPPERARY (South Riding) Issued By National Monumentsand Historic Properties Service 1997 @ Establishmentand Exhibition of Recordof Monumentsand Places under Section 12 of the National Monuments (Amendment)Act 1994 Section 12 (1) of the National Monuments(Amendment) Act 1994 states that Commissionersof Public Worksin Ireland "shall establishand maintain a recordof monumentsand places where they believethere are monumentsand the recordshall be comprisedof a list of monumentsand such places and a mapor mapsshowing each monumentand such place in respectof eachcounty in the State." Section12 (2)of the Act providesfor the exhibitionin eachcounty of the list and mapsfor that countyin a mannerprescribed by regulationsmade by the Ministerfor Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht. The relevant regulations were madeunder StatutoryInstrument No. 341 of 1994, entitled NationalMonuments (Exhibition of Recordof Monuments)Regulations, 1994. This manualcontains the list of monumentsand places recordedunder Section12 (1) of the Act for the Countyof Tipperary(South Riding) which exhibitedalong with the set of mapsfor the Countyof Tipperary(South Riding) showingthe recorded monumentsand places. Protection of Monumentsand Places included in -

Tipperary Swift Survey 2018

Tipperary Swift Survey 2018 Kevin Collins Prepared by: Will Hayes, Ricky Whelan and Brian Caffrey Project funded by: Table of Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Project Objectives ........................................................................................................................... 8 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 9 4 Data Collection .............................................................................................................................. 11 5 Citizen Science .............................................................................................................................. 12 6 Results ........................................................................................................................................... 13 6.1 Survey Visits .......................................................................................................................... 14 6.2 Swift Nests ............................................................................................................................ 17 7 Site Based Results ......................................................................................................................... 21 7.1 Clonmel ................................................................................................................................ -

Tipperary County Council Local Electoral Area

Notice of Poll Local Authority: Tipperary County Council Local Electoral Area: Clonmel Electoral Area A poll for the election of members for this local electoral area will be taken on Friday 23rd of May, 2014, between the hours of 7.00a.m. and 10.00p.m. The following are particulars of the candidates, whose names will appear on the ballot papers in the order shown: Surname Other Address Description Name and Name(s) address of proposer, if any Occupation Name of Political Party, if any Ahearn Liam Ballindoney Public Fine Gael Garrett Ahearn Grange Representative Ballindoney Clonmel Grange Co. Tipperary Clonmel Co. Tipperary Ambrose Siobhan Dún Mhuire Public Fianna Fáil Chiostóir Melview Representative McGrath Clonmel Rathkeevin Co. Tipperary Western Road Clonmel Co. Tipperary Anglim Micheál Ballylaffin Farmer/Public Fianna Fáil Ardfinnan Representative Clonmel Co. Tipperary Brunnick Kevin 55 Woodview Storeperson Sinn Féin Muiris Cahir O’Suilleabháin Co. Tipperary 3 Lisava Terrace Cahir Co. Tipperary Carey Catherine Mountain Healthcare Sinn Féin Muiris Road Worker O’Suilleabháin Clonmel 3 Lisava Terrace Co. Tipperary Cahir Co. Tipperary Condon Anne 9 O’Rahilly Retired Civil People Avenue Servant Before Profit Clonmel Alliance Co. Tipperary Egan Gabrielle 31 Public Non-Party Wheatfields Representative Ballingarrane Clonmel Co. Tipperary English Pat “Churchview” Public Workers and Cllr. Brian Rathronan Representative Unemployed O’Donnell Clonmel Action 54 Oliver Co. Tipperary Plunkett Terrace Clonmel Co. Tipperary English P.J. The Bella Farmer Fianna Fáil Oliver Keaty Road Snowdrop Clogheen Mountanglesby Cahir Clogheen Co. Tipperary Cahir Co. Tipperary Leahy Joe 79 Willow Self Employed Fine Gael Park Clonmel Co. Tipperary Lonergan Martin Curragh Secretarial Non-Party Geraldine Kelly Goatenbridge Assistant Burgessland Ardfinnan Newcastle Clonmel Clonmel Co. -

RIP.IE Deaths Tipperary Jan 1 – May 31, 2020 the Death Has Occurred of Jim COSTIGAN the Death Has Occurred of Mina Gorey (Née

RIP.IE Deaths Tipperary Jan 1 – May 31, 2020 The death has occurred of Jim COSTIGAN Moyglass, Tipperary Costigan, Moyglass, Fethard, Co. Tipperary, May 31st 2020, peacefully at Sacre Coeur Nursing Home, Tipperary. Jim, beloved husband of the late Mary. Deeply regretted by his loving family Marian, Breda, John and Catherine, daughter-in-law Dolores, sons- in-law Sean and Greg, grandchildren Emma, Laura, Barbara, Carla, Sandra, Kate and Jane, great-grandchildren Saoirse, Darragh, Eabha, Lili, Sam and Ruby, sister Nora, nieces Marie and Nuala, relatives, neighbours and friends. May He Rest In Peace Due to Government restrictions on Covid-19 Funeral takes place privately. A celebration of Jim’s life will take place when the restrictions are lifted. If you would like to leave a message of condolence for the family, please click on the link below. Date Published: Sunday 31st May 2020 Date of Death: Sunday 31st May 2020 The death has occurred of Mina Gorey (née Hayden) St Johnstown, Fethard, Tipperary Mina Gorey (nee Hayden), St Johnstown, Fethard, Co Tipperary and formerly of Old Grange, Graiguenamanagh, May 30th 2020, peacefully, at home. Pre-deceased by her husband Sean, brother Pat and grand daughter Ruth. Very deeply regretted by her loving family;Lilian, Denis, Paddy and Marina, daughters in law Mary (Drangan), Mary (Kilbehenny), son in law David, sister in law Vera Hayden, grand children Shane, Patrick, Conor, Andrew, Emily, Louis, Austen, Lara and Sophie, nieces, nephews, relatives, neighbours and friends. May she rest in peace. Due to Government and HSE restrictions, Mina's funeral will be private. -

Settlement Nodes - South Tipperary County TABLE of CONTENTS Development Plan 2009 (As Varied) AHENNY

South Tipperary County Development Plan 2009 (as varied) 2015 Settlement Nodes - South Tipperary County TABLE OF CONTENTS Development Plan 2009 (as varied) AHENNY .............................................................................................................. 2 ARDMAYLE ......................................................................................................... 3 BALLAGH ............................................................................................................ 4 Village statements for the villages designated as Settlement Nodes are outlined BALLINURE ......................................................................................................... 5 below and comprise a written statement and associated Map. BALLYLOOBY...................................................................................................... 6 Landuse zoning categories are indicated in this Plan (as varied) and are set out BALLYNEILL ........................................................................................................ 7 below. The land use zoning objectives should be read in conjunction with the COALBROOK ...................................................................................................... 8 Village Statements and associated Maps. CULLEN ............................................................................................................... 9 There are 25 Settlement Nodes as outlined in the Settlement Strategy (Chapter FAUGHEEN ...................................................................................................... -

Settlement Hierarchy

Settlement Hierarchy Introduction The Corporate Vision for Tipperary County Council enshrines the principle of Tipperary as a desirable place to live, with attractive towns and picturesque and vibrant villages, surrounded by beautiful countryside. In line with this vision, it is planned that future population growth in the county will be accommodated in existing towns, villages in line with a county settlement hierarchy, and also through sensitive development in the countryside, with infrastructure delivered in a timely fashion to ensure sustainable and inclusive communities. Tipperary County Council has at present two County Development Plans; as follows: South Tipperary County Development Plan 2009 (as varied) North Tipperary County Development Plan 2010 (as varied) In 2015, the Council put in place a new strategic county-wide planning framework, which included the development of a new County Settlement Hierarchy to facilitate the development of sustainable communities throughout the county. The County Settlement Hierarchy was incorporated into both County Development Plans by way of a variation process. The Settlement Hierarchy is consistent with the National Spatial Strategy and Regional Planning Guidelines, while recognising the diversity of scale, character of the county’s towns and villages. Each settlement has a complementary role in achieving growth and prosperity in the county. It is recognised that rural villages, along with the large towns, play an essential role by acting as sustainable development centres within rural communities. The Settlement Hierarchy, associated location map, and an outline of the role and function of each settlement is set out below. Figure 1: Tipperary County Settlement Hierarchy Regional Town Clonmel Sub-Regonal Towns Nenagh & Thurles District Towns Carrick on Suir, Roscrea, Tipperary, Cashel, Cahir and Templemore.