RCEWA – an Academy by Lamplight by Joseph Wright of Derby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supporting Evidence

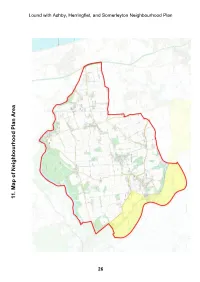

Lound with Ashby, Herringflet, and Somerleyton Neighbourhood Plan 11. Map Neighbourhoodof Plan Area 26 Lound with Ashby, Herringflet, and Somerleyton Neighbourhood Plan 12. Application to designate Plan Area. 27 Lound with Ashby, Herringflet, and Somerleyton Neighbourhood Plan 13. Decision Notice from Waveney District Council 28 Lound with Ashby, Herringflet, and Somerleyton Neighbourhood Plan 14. Statement of Consultation. 14.1 Consultation meetings held on 13th November 2016. Informal open meetings were held at Somerleyton and Lound village halls. These meetings were advertised by delivering a flyer to every house in the two parishes, and by putting posters on the village notice boards and websites. A letter was also sent to all local businesses and other local organisations. The events were well attended, with 50 people visiting Somerleyton village hall, and 28 people visiting Lound village hall Consultation meeting at Somerleyton Post-it notes for residents’ comments Residents were able to view maps and to comment on various local issues using ”post-it” notes, which proved a very successful way of collecting their views. At the end of the meetings 330 comments had been received, and these were analysed. A summary of the comments which was displayed on the village notice boards and websites, and is shown below: NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 29 Lound with Ashby, Herringflet, and Somerleyton Neighbourhood Plan CONSULTATION DAY 13TH NOVEMBER 2016 THE KEY ISSUES RAISED BY THE COMMUNITY WERE: Housing. Avoid building new houses on some specified sites, although some acceptable sites were identified. The Blundeston prison site and brownfield sites in Lowestoft are more suitable. New development should be limited to small houses. -

Waveney District Council Local Plan Examination Evolution Town

Waveney District Council Local Plan Examination Evolution Town Planning Representing The Somerleyton Estate – Matter Statement ‐ Matter 8 September 2018 Opus House 01359 233663 Waveney District Council Local Plan Examination Evolution Town Planning Representing The Somerleyton Estate – Matter Statement ‐ Matter 8 E374.C1.Rep010 Page 2 of 11 E374.C1.Rep010 September 2018 1.0 Matter 8: Strategy for Rural Areas Allocation Sites Policy Reference WLP 7.5 Land North of The Street Somerleyton and WLP7.6 Mill Farm Field, Somerleyton Introduction 1.1 This Matter Statement has been prepared on behalf of the Somerleyton Estate and supports the above two housing allocations on Estate land in Somerleyton village. The Mill Farm Field allocation has been reduced from 45 to 35 homes and this statement sets out why the allocation should be increased to 45 homes. 1.2 This Matter Statement answers the Inspectors questions which are: “Are the allocations for development soundly‐based; are the criteria set out in the relevant policies justified and effective; and is there evidence that the development of the allocations is viable and deliverable in the timescales indicated in Appendix 3 of the plan?” 1.3 We are clear that the allocations are soundly based, are an appropriate strategy, and are deliverable. The landowner is advised on estate management, and development matters by Savills. Savills advice is that the allocations are viable and deliverable. The landowner has housebuilder interest in the allocations, and we are confident that they can come forward within the timescales set out in Appendix 3 of the Local Plan. 1.4 We firstly set out the background to the village and the allocations. -

Lound with Ashby, Herringfleet and Somerleyton Neighbourhood Plan

Lound with Ashby, Herringfleet and Somerleyton Neighbourhood Plan 2014 to 2036 Submission Version July 2021 Lound with Ashby, Herringfleet and Somerleyton Neighbourhood Plan Index 1. Introduction page 2 2. Map of Neighbourhood Plan Area page 3 3. Profile of the Parishes page 4 4. Our Vision for 2036 page 6 5. Objectives of Neighbourhood Plan page 6 6. Policies included in this Neighbourhood Plan page 8 7. Housing page 8 8. Environment page 17 9. Community Facilities page 21 10. Business and Employment page 27 11. Health page 28 Appendix 1 Lound and Somerleyton, Suffolk, Masterplanning and Design Guidelines, AECOM, June 2019 1 Lound with Ashby, Herringfleet and Somerleyton Neighbourhood Plan 1. Introduction 1.1 Lound and Ashby, Herringfleet & Somerleyton are adjoining parishes in the north of Suffolk. The area is rural, with much of the land being used for agriculture. The main settlement areas are the villages of Somerleyton and Lound, with smaller settlements at Herringfleet and Ashby, together with some scattered farmhouses and converted farm buildings or farm workers’ cottages. The two parishes have a combined area of around 2020 hectares, and a total population of around 780 (2011 census). 1.2 Early in 2016 the two parish councils agreed to work together to develop a joint neighbourhood plan. A steering group consisting of residents and Parish Councillors was set up to lead the work. 1.3 One of the initial pieces of work was to agree and gain acceptance from the former Waveney District Council (now East Suffolk Council) and the Broads Authority for the designated Neighbourhood Area. -

Tank Training Site, Fritton Lake Somerleyton, Ashby & Herringfleet HER Ref. SOL

Tank Training Site, Fritton Lake Somerleyton, Ashby & Herringfleet HER ref. SOL 029 Archaeological Survey Report SCCAS Report No. 2013/052 Client: Suffolk County Council Author: Mark Sommers April 2013 © Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service Tank Training Site, Fritton Lake Somerleyton, Ashby & Herringfleet HER ref. SOL 029 Archaeological Survey Report SCCAS Report No. 2013/022 Author: Mark Sommers Contributions By: Stuart Burgess Report Date: April 2013 HER Information Site Code: SOL 029 Site Name: World War 2 Tank Training Site, Fritton Lake Report Number 2013/052 Planning Application No: n/a Date of Fieldwork: 25th - 28th April 2013 Grid Reference: TM 4803 9977 Oasis Reference: suffolkc1-148843 Curatorial Officer: Sarah Poppy Project Officer: Mark Sommers Client/Funding Body: funded by the European Interreg IV Project Client Reference: n/a Digital report submitted to Archaeological Data Service: http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/library/greylit Disclaimer Any opinions expressed in this report about the need for further archaeological work are those of the Field Projects Team alone. Ultimately the need for further work will be determined by the Local Planning Authority and its Archaeological Advisors when a planning application is registered. Suffolk County Council’s archaeological contracting services cannot accept responsibility for inconvenience caused to the clients should the Planning Authority take a different view to that expressed in the report. Prepared By: Mark Sommers Date: April 2013 Approved By: Dr Rhodri Gardner Position: Contracts Manager Date: April 2013 Signed: Contents Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. Location 3 3. Historic Background 3 4. Methodology 3 5. Survey Results 4 1. Military camp 5 2. -

Southwold Cottage Region: Suffolk Sleeps: 6

Southwold Cottage Region: Suffolk Sleeps: 6 Overview The delightful and beautifully restored Victorian Southwold Cottage is located in a quiet spot in the heart of the trendy Suffolk town of Southwold. With spacious accommodation for six plus a dog, this wonderful holiday home is a fabulous base. The ever popular Southwold is fantastic with charming independent shops, cosy restaurants and pubs and a wonderful beach featuring colourful beach huts. Southwold is one of Suffolk’s most picturesque seaside towns, and it is easy to see why Southwold Cottage is booked so frequently. The cottage was recently refurbished to a very high standard. It is stylish, superbly comfortable and offers super comfy furnishings, a gourmet kitchen, a cosy wood-burning stove and three spectacular bedrooms. Much attention has been given to the detail, and the colour palettes are wonderful. The living area is open plan in design with a stylish and comfortable lounge around the wood burner, an elegant dining table and a top-notch kitchen. The DeVol kitchen cabinets are painted a cool olive colour, and the kitchen is complete with a Miele range cooker, other Miele appliances, a Belfast sink and, of course, a Nespresso coffee machine. Sparkling white countertops and striking bronze taps complete the picture giving you no excuse not to come up with a delicious gourmet meal. Guests can sit at the quality dining table with a glass of wine, keeping the chef company! All three bedrooms are upstairs in various muted shades of blue. You can choose been the Cornish, azure or eggshell blue panelled rooms, all of which offer a warm and elegant ambience. -

A History of Landford in Wiltshire

A History of Landford in Wiltshire Part 3 – Landford Manor This history of Landford Manor and estate has been compiled from various sources using the Internet. Not all sources are 100% reliable and subsequently this account may also perpetuate some of those errors. The information contained in this document is therefore for general information purposes only and whilst I have tried to ensure that the information given is correct, I cannot guaranty the accuracy or reliability of the sources used or the information contained in this document. Page 2. Section 1 - The history of Landford Manor Page 7. Section 2 - Table of Owners and Occupiers of Landford Manor Page 8. Section 3 - Family connections with Landford Manor Page 8 The Lye/Lygh/Leyh, Stanter and Beckett families Page 10 The Dauntsey/Stradling/Danvers families Page 11 The Davenant family Page 13 The Eyre family Page 20 Worsop and Trollope Page 21 The Jeffreys family Page 23 Mrs Sarah Maud Crossley Page 24 Sir Alfred Mond Page 26 Sir Frederick Preston Page 28 Margaret Bell Walmsley Page 30 Extracts from the Newspapers Page 33 Acknowledgements John Martin (Aug 2019) Page 1 of 34 A History of Landford in Wiltshire Part 3 – Landford Manor Section 1 – The history of Landford Manor Much of the following information regarding the history of Landford Manor is taken from Some Notes on the Parish of Landford written in 1872 by Rev F.G. Girdlestone, and from the Wiltshire Community History and the British History online websites. I have added further notes on the family connections with Landford Manor to try and provide some insight into the people that occupied the property. -

All Approved Premises

All Approved Premises Local Authority Name District Name and Telephone Number Name Address Telephone BARKING AND DAGENHAM BARKING AND DAGENHAM 0208 227 3666 EASTBURY MANOR HOUSE EASTBURY SQUARE, BARKING, 1G11 9SN 0208 227 3666 THE CITY PAVILION COLLIER ROW ROAD, COLLIER ROW, ROMFORD, RM5 2BH 020 8924 4000 WOODLANDS WOODLAND HOUSE, RAINHAM ROAD NORTH, DAGENHAM 0208 270 4744 ESSEX, RM10 7ER BARNET BARNET 020 8346 7812 AVENUE HOUSE 17 EAST END ROAD, FINCHLEY, N3 3QP 020 8346 7812 CAVENDISH BANQUETING SUITE THE HYDE, EDGWARE ROAD, COLINDALE, NW9 5AE 0208 205 5012 CLAYTON CROWN HOTEL 142-152 CRICKLEWOOD BROADWAY, CRICKLEWOOD 020 8452 4175 LONDON, NW2 3ED FINCHLEY GOLF CLUB NETHER COURT, FRITH LANE, MILL HILL, NW7 1PU 020 8346 5086 HENDON HALL HOTEL ASHLEY LANE, HENDON, NW4 1HF 0208 203 3341 HENDON TOWN HALL THE BURROUGHS, HENDON, NW4 4BG 020 83592000 PALM HOTEL 64-76 HENDON WAY, LONDON, NW2 2NL 020 8455 5220 THE ADAM AND EVE THE RIDGEWAY, MILL HILL, LONDON, NW7 1RL 020 8959 1553 THE HAVEN BISTRO AND BAR 1363 HIGH ROAD, WHETSTONE, N20 9LN 020 8445 7419 THE MILL HILL COUNTRY CLUB BURTONHOLE LANE, NW7 1AS 02085889651 THE QUADRANGLE MIDDLESEX UNIVERSITY, HENDON CAMPUS, HENDON 020 8359 2000 NW4 4BT BARNSLEY BARNSLEY 01226 309955 ARDSLEY HOUSE HOTEL DONCASTER ROAD, ARDSLEY, BARNSLEY, S71 5EH 01226 309955 BARNSLEY FOOTBALL CLUB GROVE STREET, BARNSLEY, S71 1ET 01226 211 555 BOCCELLI`S 81 GRANGE LANE, BARNSLEY, S71 5QF 01226 891297 BURNTWOOD COURT HOTEL COMMON ROAD, BRIERLEY, BARNSLEY, S72 9ET 01226 711123 CANNON HALL MUSEUM BARKHOUSE LANE, CAWTHORNE, -

Gunton Hall & Suffolk

WITH WARNER LEISURE HOTELS Gunton Hall & Suffolk Discover our hotel and the outdoors East Anglia is a region of fine contrasts with flat farmland and acres of countryside extending out to attraction-packed seaside resorts, royal estates and ancient settlements. There’s something for all tastes here. Norfolk and Suffolk share a glorious and largely untamed coastline, which is laced with a score of traditional seaside towns and sandy Blue Flag beaches. Inland, the scene is just as appealing, with medieval towns and villages full of history and culture. Adventure is always waiting too in the forests and on the network of rivers and lakes that make up the Norfolk Broads. Let’s not forget either that this is the bird-watching capital of Britain with a magnificent variety of bird life making the nature reserves their home. We’ve partnered with ViewRanger to POSTCODE & OPENING PARKING create walking routes for all levels of DIRECTIONS HOURS CHARGES ability – tap here for more info. Gunton Hall & Suffolk || Discover our hotel and the outdoors THE BEST OF OUR GROUNDS AND GARDENS We’re so proud of our grounds here at Gunton Hall, with formal gardens, the beautiful lake, and the abundance of daffodils we enjoy every springtime. Our team have picked out three of their favourite things to do within the grounds, just for you: The lake The half-mile walk that surrounds our lake leads directly to our waterside hide, perfect for watching the birds flitter between the woodland and the water, with the relaxing sound of our fountains in the background. -

Ellis Wasson the British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2

Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński ISBN 978-3-11-056238-5 e-ISBN 978-3-11-056239-2 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. © 2017 Ellis Wasson Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Thinkstock/bwzenith Contents The Entries VII Abbreviations IX List of Parliamentary Families 1 Bibliography 619 Appendices Appendix I. Families not Included in the Main List 627 Appendix II. List of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 648 Indexes Index I. Index of Titles and Family Names 711 Index II. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 769 Index III. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by County 839 The Entries “ORIGINS”: Where reliable information is available about the first entry of the family into the gentry, the date of the purchase of land or holding of office is provided. When possible, the source of the wealth that enabled the family’s election to Parliament for the first time is identified. Inheritance of property that supported participation in Parliament is delineated. -

Ellis Wasson the British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2

Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński ISBN 978-3-11-056238-5 e-ISBN 978-3-11-056239-2 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. © 2017 Ellis Wasson Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Thinkstock/bwzenith Contents The Entries VII Abbreviations IX List of Parliamentary Families 1 Bibliography 619 Appendices Appendix I. Families not Included in the Main List 627 Appendix II. List of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 648 Indexes Index I. Index of Titles and Family Names 711 Index II. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 769 Index III. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by County 839 The Entries “ORIGINS”: Where reliable information is available about the first entry of the family into the gentry, the date of the purchase of land or holding of office is provided. When possible, the source of the wealth that enabled the family’s election to Parliament for the first time is identified. Inheritance of property that supported participation in Parliament is delineated. -

SUFFOLK. CUT 389 Cooper Mrs

COURT DIREafORY.] SUFFOLK. CUT 389 Cooper Mrs. East view, Cauldwell Cowell G. Ulcombe, Snape, Saxmndhm Crossley Sir Savile Brinton bart. !full road, Ipswich <Xlwell Herbert J.P. Brudenell ter- J.Y. Somerleyton hall, Lowestoft Cooper Mrs. Oak cottage, Blundes- race, Aldeburgh R.S.O Crossman E. 25 Out Northgate, Bury ton, Lowestoft Cowell Miss, South lawn, Anglesea Crossman Percy, Barham, Ipswich Cooper Mrs. Stradbroke, Eye road, Ipswich Crouch Oliver, 39 Spring rd. Ipswich Cooper Mrs. C. Kessingland, Lowestoft Cowell WaIter Samuel, The Poplars, Grow Mrs. Stour cot. Clare R.S.O Cooper Mrs. E. Higham hall, Colchstr Henley road, Ipswich Crowe Misses, 4 Nelson ter. Felixstow~ Cooper Reed, 9 Northgate street, Bury Cowen John, Cemetery rd. Mildenhall CrowB Mrs. Wiekham, Market Cooper Robert, Creeting St. Mary, Cowles Denis J., M.A. Manor house, Crowe W. Russell, Hill house, Little Neediham Market Felixstowe Wratting, Haverhill Cooper S. H. Needham Market R.S.O Cowles Miss, Northgate street,Becdes Crowe Wm. Melton hill, Woodbridge Cooper Thomas, 2 May villas, Quilter Cox Arthur, 343 London road south, Crowfoot Misses,Blyburgate st.Beccle5 road, Felixstowe Kirkley, Lowestoft Crowfoot Mrs. J. R. Esborne house, Cooper W. 144 Woodbridge rd. Ipswch Cox Arthur, I Rectory road, Kirk- Saltgata street, Beccles Cooper Waiter, New York villa, Felix- ley, Lowestoft Crowfoot William Miller M.B., J.P:. Stowe road, Ipswich Cox Mrs.239Cauldwell 'Hall rd.Ipswich The 'Walk, Beccles Cooper William, 291 London road Cox Robert, I High beach, Felixstowe Crowhurst J. The Gables, Felixstowe south, Kirkley, Lowestoft Cox Wm. Thos. 8 Albert street, Bury Croydon Oharles Edward, Rose cot~ Cooper William Beckett, (Highdene, Coxhead Miss,36Palmerston rd.Ipswch tage, Constable road, Felixstowe Park road, Lowestoft Coy John, White ho. -

Lowestoft Pocket Guide

5 From Beaches … LOWESTOFT MAPS, WALKS & INFO Whether you want to be king of the sand- castle, ace of seaside spades or just enjoy some DISCOVER LOWESTOFT traditional downtime in the deckchair, Lowestoft’s brilliant collection of award-winning Fa Golden sands, glorious green spaces & history all around beaches has something for everyone. Feel the mil LOWESTOFT Edged by brilliant award-winning beaches, the Broads National Park and an super-soft, golden sand between your toes on Ga y M South Beach by the piers, alongside the colourful cabins at its F Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, the north Suffolk home of Britain’s most a t un Victoria Beach ri E e easterly resort really is an all-round breath of fresh air. , or stroll south to discover the rural calm and ngl t w im curvaceous charm of the boat-dotted beach at * The Guide to Pocket a Enjoy bucket-loads of traditional seaside fun. Ride rollercoasters. Meet Pakefield T . a y t e Similar to o Corton/Gunton Sands n north of town, its vegetated meerkats. Go time-travelling on vintage vehicles. Explore architectural gems and w d H o sand and shingle-scapes seem worlds away from the gentle 1920s ’ s n t ancient alleyways. Taste fresh fish and chips. Savour quiet moments by Morton i s M h t elegance of Kensington Gardens back around the Kirkley Cliff corner. & o Peto’s historic Lowestoft quayside. Watch boats by Oulton Broad, or the birds by e os r Further south sand-dune and shingle stretches at Co B y the marshes maybe? Discover the elegant tranquillity of Lowestoft’s heritage Kessingland seem wilder t r & still, home to yellow sea poppies, sea peas and nesting Little terns.