UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recent Publications Relating to the Work of EUGEN ROSENSTOCK-HUESSY 1973 to the Present

1 eeee Recent Publications Relating to the Work of EUGEN ROSENSTOCK-HUESSY 1973 to the Present (Listed by date of publication unless otherwise noted) (As of June 10, 2013 –A compilation in continuous progress) CONTENTS - I. Books - II. Journal Articles, Essays in Collections, and Book Reviews - III. Online/Electronic - IV. Ph. D. Dissertations, Encyclopedia Entries, and Other Special Formats - V. Publications of the Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy Gesellschaft - VI. Unpublished Conference Presentations and the Like ___________________ Corrections or comments concerning this list should be sent to: [email protected] or to Norman Fiering, P. O. Box 603233, Providence, RI 02906. For information about joining the ERH Society, please write to the same. - I. BOOKS - 2 I. BOOKS •Raley, Harold C., José Ortega y Gasset: Philosopher of European Unity (University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1971). Ortega and R-H have much in common, particularly in their understanding of history. Raley cites R-H in a number of footnotes and is full of praise (cf. p. 123n): “In language as powerful as Ortega’s and with an understanding at least as deep, [R-H] says of Rationalism: ‘The abstractions that prevailed in philosophy from Descartes to Spencer, and in politics from Machiavelli to Lenin, made caricatures of living men. etc.’” quoting from Out of Revolution. The European Union is in a phase now of determining essentially what “Europe” means, which inescapably calls attention to “its” history. Out of Revolution should find new readers because of this quest. Raley says of Out, “An extraordinary, indeed a stupendous, achievement in historiography, with fresh original insights on virtually every one of its 800 pages.” •Ritzkowsky, Ingrid, Rosenstock-Huessys Konzeption einer Grammatik der Gesellschaft (Berlin, 1973) • Rohrbach, Wilfrid, Das Sprachdenken Eugen Rosenstock-Huessys; historische Erörterung und systematische Explikation (Stuttgart: W. -

Page Smith Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6f59s0hd No online items Page Smith papers, ca. 1952-1964 Finding aid prepared by UCLA Library University Archives staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Finding aid last modified on 13 April 2016. Page Smith papers, ca. 620 1 1952-1964 Title: Page Smith papers Collection number: 620 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 15.0 linear ft.(15 cartons) Date (inclusive): ca. 1952-1964 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Smith, Page 1917-1995 Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. Provenance/Source of Acquisition The Page Smith Papers were acquired in 2004 from the Page Smith family and in cooperation with the Special Collections and Archives of the Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. -

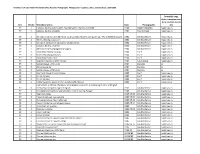

UA 128 Inventory Photographer Neg Slide Cs Series 8 16

Inventory: UA 128, Public Information Office Records: Photographs. Photographer negatives, slides, contact sheets, 1980-2005 Format(s): negs, slides, transparencies (trn), contact sheets Box Binder Title/Description Date Photographer (cs) 39 1 Campus, faculty and students. Marketing firm: Barton and Gillet. 1980 Robert Llewellyn negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Paul Schraub negatives, cs 39 2 Set construction; untitled Porter sculpture (aka"Wave"); computer lab; "Flying Weenies"poster 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Tennis, fencing; classroom 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Bike path; computers; costumes; sound system; 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Admissions special programs (2 pages) 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown family housing 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Student family apartments 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown Santa Cruz 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Special Collections, UCSC Library 1984 Lucas Stang negatives, cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Childcare center 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 East Field House; Crown College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Performing Arts; Oakes; Porter sculpture (The Wave) 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs Jack Schaar, professor of politics; Elena Baskin Visual Arts, printmaking studio; undergrad 39 3 chemistry; Computer engineering lab -

COLLEGE EIGHT FROSH WELCOME to UCSC Welcome to UC Santa Cruz and Congratulations! This Is a Very Exciting Time in Your Life As You Begin a New Phase of Learning

ENVIRONMENT SOCIETY COLLEGE EIGHT FROSH Welcome Week Guide 2014 Week Welcome COLLEGE EIGHT WELCOME TO UCSC Welcome to UC Santa Cruz and congratulations! This is a very exciting time in your life as you begin a new phase of learning. Every year students tell us that a key factor to their success is getting involved on campus and making a difference in their community. We hope you take advantage of this week to learn as much as possible about your new environment. Fall Welcome Week has been planned for you to learn about the academic resources, to become familiar with the campus, and to learn about the Santa Cruz community. Use this guide to learn about the many workshops/events taking place campus-wide during Fall Welcome Week. Notice that some events are MANDATORY. Your academic and social transition to UC Santa Cruz is extremely important to us. We consider you a partner in your academic and social success here. Therefore we expect you to actively participate in the many programs and services this first week and well beyond. So, start now and begin making connections! 1 WELCOME TO COLLEGE EIGHT Welcome to College Eight and UC Santa Cruz! There are a number of things you’ll need to accomplish during your first several days on campus. This Orientation Schedule is designed to help guide you. Use it to learn about the many workshops, orientations, office hours and events across campus during Welcome Week. If you need more information ask an Orientation Leader (OL), Programs Assistant (PA), Resident Assistant (RA) or a member of our college staff. -

Introduction the Regional History Project Conducted Five Interviews

Introduction The Regional History Project conducted five interviews with Page Smith from January 23 to July 17, 1974, as part of its University History series. During the last interview session, Smith informed his interviewer, Elizabeth Calciano, that he had second thoughts about publishing an edited transcript (which had been the understanding at the start of the interview project) and that he preferred instead that people listen to the tape-recordings. The release of the infamous Watergate tapes influenced his decision; he believed at the time that a written transcript would not accurately convey the content or tone of his spoken interviews and wanted no ambiguity in his recollections. The concluding chapter of this volume (Smith’s Second Thoughts about this Oral History”) contains his reasons for this change of heart. Calciano told Smith that she would put the transcript away and hoped that he would reconsider releasing the manuscript at a later date. In 1987 I met with Smith at his home in Bonny Doon, gave him an edited transcript and requested that he read it over, make corrections, and consider releasing the printed text. I heard nothing from him but assumed that someday the manuscript would be published. Smith died in Santa Cruz on August 28, 1995, of leukemia. In November, 1995, I wrote Smith’s daughter, Anne Easley, and explained the circumstances surrounding the oral history. I gave her a copy of her father’s transcript, asked if she could find the manuscript I’d given him, and requested that she consider with her family the possibility of publishing the volume. -

2020-21 DOMESTIC EXCHANGE PROGRAM APPLICATION Note: the Last Day to Submit This Application to the Office of the Registrar Is Feb

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR Registrar, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Phone (831) 459-4412 • FAX (831) 459-5051 [email protected] 2020-21 DOMESTIC EXCHANGE PROGRAM APPLICATION Note: The last day to submit this application to the Office of the Registrar is Feb. 22, 2020. After Feb. 22, 2020, contact [email protected] for assistance. For more information, see the Domestic Exchange Programs webpage. REQUESTOR Name (Last, First, Middle) _____________________________________________________________________________ Student ID __________________________________________ Birthdate ______________________________________ College ___________________________________________ Major ___________________________________________ Total credits (including this quarter) _____________________ ACADEMIC LEVEL Frosh Sophomore Junior Senior FINANCIAL AID I expect to receive UCSC financial aid during the exchange period. Yes No PREFERENCES University University of New Hampshire University of New Mexico Period 202020-21 Academic Year 202020 Fall Semester Only 202021 Spring Semester Only Please complete page 2 and the Proposed Course Study Plan beginning on page 3. Page 1 of 5 Revised: 11/27/2019 DIVISION OF UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION Rachel Carson College • Cowell College • Crown College • Kresge College • Merrill College • Oakes College • Porter College • Stevenson College Campus Orientation • Enrollment Management • Financial Aid and Scholarships • Office of the Registrar • Undergraduate Admissions Campus Advising Coordination • Educational Partnership Center • Office of the Vice Provost and Dean • Summer Session UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR Registrar, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 Phone (831) 459-4412 • FAX (831) 459-5051 [email protected] 2020-21 DOMESTIC EXCHANGE PROGRAM APPLICATION Note: The last day to submit this application to the Office of the Registrar is Feb. 22, 2020. -

Conference Services Parking

WHERE TO FIND HELP CAMPUS HOT SPOTS Science Hill 7 Conference Offices College Ten Arboretum & Botanic Garden 1 The buildings on UCSC’s Science Hill include the College Nine Crown College There are Conference Offices in various locations award-winning Science and Engineering Library, The UCSC Arboretum & Botanic Garden is a set amid redwood trees and open to the public; on campus with friendly and knowledgeable staff to research and teaching facility serving the campus and assist you. Locations and hours are listed below: Sinsheimer Laboratories, housing the Biology 167 the public. Particular specialties are conifers, primitive Department; Thimann Laboratories, housing the North Perimeter angiosperms, and plant families of the Southern West Conference Office W Parking Lot Chemistry and Biochemistry Department; the 150 Hemisphere. Located near the intersection of Empire Earth and Marine Sciences Building, housing the Social Grade and Western Drive, the Arboretum is open to 7:00 am–8:00 pm Sciences 1 Earth and Planetary Sciences and Ocean Sciences 156 154 155 the public daily with an entrance fee of $5.00. Norrie’s Porter College Apt. E #104 RV * * Departments; and Natural Sciences 2, housing the Park Social 153 152 139 Sciences 2 Gift Shop is also open daily. arboretum.ucsc.edu Phone: (831) 502-7000 165 166 Firehouse Environmental Studies Department as well as the Serving: Rachel Carson, Oakes, Porter and Kresge 139 Center for Adaptive Optics. Access to Science Hill is 139 111 123 Merrill College ATMs 2 off McLaughlin Drive. oad University R 111 Engineering 2 n ** East Conference Office E 123 Center Bank ATMs, accepting most cards, are located just 164 8 111 139* Communications Co-gen quapi 111 across from the Bay Tree Bookstore. -

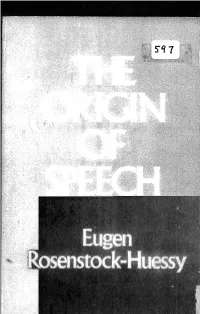

The Origin of Speech

THE ORIGIN OF SPEECH THE ORIGIN OF SPEECH Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy INTRODUCTION BY HAROLD M. STAHMER ARGO BOOKS NORWICH, VERMONT Copyright © 1981 by Argo Books, The Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy Fund, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. Published by Argo Books, Norwich, Vermont 05055. Copies of this book may be obtained from the publisher at that address; in Europe copies are available from Argo Books, Pijperstr. 20, Heemskerk, Netherlands. FIRST EDITION *1 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Rosenstock-Huessy, Eugen, 1888-1973. The origin of speech. Based in part on: Die Sprache des Menschengeschlechts. Bibliography: p. Includes index. * 1. Language and languages — Origin — Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Languages — Philosophy — Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Title. P116.R67 1981 40T.9 81-20527 ISBN 0-912148-13-6 (pbk.) AACR2 Contents INTRODUCTION IX by Harold M. Stahmer 1 THE AUTHENTIC MOMENT OF SPEECH 2 Pre-formal, formal, informal speech — the father explains the child — formal speech is naming speech — names and pronouns — politics and religion create new speech 2 THE FOUR DISEASES OF SPEECH 10 War, crisis, revolution and decay — healthy speech creates peace, trust, respect, freedom — formal speech: the spoken and written word 3 CHURCH AND STATE OF PREHISTORIC MAN 19 From tomb to womb — death is the womb of time — the origin of human -

A Pluralistic University: William James and Higher Education Pamela Castellaw Crosby

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 A Pluralistic University: William James and Higher Education Pamela Castellaw Crosby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION A PLURALISTIC UNIVERSITY: WILLIAM JAMES AND HIGHER EDUCATION By PAMELA CASTELLAW CROSBY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Pamela C. Crosby, defended on June 16, 2008. _____________________________________ Jeffrey A. Milligan Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Peter Dalton Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Jon C. Dalton Committee Member _____________________________________ Emanuel Shargel Committee Member Approved: _______________________________ Gary Crow, Chair, Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii I dedicate this work to Dr. Donald A. Crosby, my husband, best friend, soul mate, and the one who introduced me to William James. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the members of my dissertation committee for their guidance throughout the dissertation process: Dr. Jeff Milligan, for teaching me to be an independent scholar, yet providing me with the direction and support that I needed when I stumbled and veered off course; Dr. Jon Dalton, for treating me as a junior colleague while at the same time offering me his ongoing mentorship; Dr. Peter Dalton, for teaching me what outstanding teachers do both inside and outside the classroom; and Dr. -

UC Santa Cruz Photographs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8bz6csd No online items Guide to UC Santa Cruz Photographs Mary deVries University of California, Santa Cruz 2016 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Guide to UC Santa Cruz UA.083 1 Photographs Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: UC Santa Cruz Photographs Identifier/Call Number: UA.083 Physical Description: 1 Linear Feet4 boxes Date (inclusive): 1919-2005 Date (bulk): 1965-2005 Access to Collection Collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. For more information on copyright or to order a reproduction, please visit guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll/reproduction-publication. Preferred Citation UC Santa Cruz Photographs. UA 83. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Scope and Content The collection contains photographic prints, slides, transparencies and negatives of the UCSC campus from 1919 to 2005. Images include scenes from daily campus life and activities, and people and events significant to UCSC history. These are images that were taken by, or donated by, various parties with no other associated collection materials. Or, they are of unknown origin. -

The War Against Nature: Benton Mackaye's Regional Planning

THE WAR AGAINST NATURE: BENTON MACKAYE’S REGIONAL PLANNING PHILOSOPHY AND THE PURSUIT OF BALANCE by Julie Ann Gavran APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Eric R. Schlereth, Chair ___________________________________________ Matthew J. Brown ___________________________________________ Pamela S. Gossin ___________________________________________ Peter K. J. Park Copyright 2017 Julie Ann Gavran All Rights Reserved THE WAR AGAINST NATURE: BENTON MACKAYE’S REGIONAL PLANNING PHILOSOPHY AND THE PURSUIT OF BALANCE by JULIE ANN GAVRAN, BA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – HISTORY OF IDEAS THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have received tremendous support from many individuals in the past thirteen years. Drs. John Marazita and Ron Carstens have been mentors, colleagues, and friends from my early academic beginning at Ohio Dominican University. I would especially like to thank my dissertation chair, Dr. Eric Schlereth, for providing me with the final push and guidance to complete this project. I would like to thank the rest of my committee, Drs. Matthew Brown, Pamela Gossin, and Peter Park, for your support throughout the many years of coursework and research, and for helping lay the foundation of this project. I would like to thank the countless people I spoke to throughout the many years of research, especially the staff at Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, and the many people who knew Benton personally. Finally, thanks to Drs. Jim Cannici and Gabe Yeamans for providing me lending ears and hearts without which I could not have finished this project. -

Co Well Frosh

Welcome Week Guide 2014 COWELL FROSH Welcome to UCSC Welcome to UC Santa Cruz and congratulations! This is a very exciting time in your life as you begin a new phase of learning. Every year students tell us that a key factor to their success is getting involved on campus and making a difference in their community. We hope you take advantage of this week to learn as much as possible about your new environment. Fall Welcome Week has been planned for you to learn about academic resources, to become familiar with the campus, and to learn about the Santa Cruz community. Use this guide to learn about the many workshops/events taking place campus-wide during Fall Welcome Week. Notice that some events are MANDATORY. Your transition to UC Santa Cruz is extremely important to us. We consider you a partner in your academic and social success here. Therefore we expect you to actively participate in the many programs and services this first week and well beyond. So, start now and begin making connections! 1 Cover artwork by Shelby Heinzer, Class of 2014 Welcome to Cowell Welcome to Cowell College! There are a number of things you’ll need to accomplish during your first several days on campus. This Welcome Week Guide is designed to help. Use it to learn about the many workshops, orientations, office hours and events across campus during Welcome Week. Table of Contents: Week Planner . 3-5 Welcome Week Resources. .7-9, 29 ID Card Services. 6 Residental Network Help. 8 Library Info & Tours. 8 Student Services Office Hours.