16. Some People Call Him a Space Cowboy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebels Season 2 Sourcebook Version 1.0 March 2017

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away... CREDITS I want to thank everyone who helped with this project. There were many people who helped with suggestions and editing and so many other things. To those I am grateful. Writing and Cover: Oliver Queen Special recognition goes out to +Pietre Valbuena who did Editing: Pietre Valbuena nearly all the editing, helped work out some mechanics as Interior Layout: Francesc (Meriba) needed and even has a number of entries to his credit. This book would not be anywhere near as good as it presently is without his involvement. The appearance of this book is credited to the skill of Francesc (Meriba). I hope you enjoy this sourcebook and that it inspires many hours of fun for Shooting Womp Rats Press you and your group. Star Wars Rebels Season 2 Sourcebook version 1.0 March 2017 May the Force be With You, Oliver Queen Table of contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 2 ENERGY WEAPONS .................................................. 88 CHAPTER 1: HEROES OF THE REBELLION .......... 4 Blasters .................................................................... 88 THE SPECTRES ............................................................. 4 Other weapons ...................................................... 91 “Spectre 1” Kanan Jarrus .......................................... 4 EXPLOSIVES AND ORDNANCE .......................... 92 “Spectre 2” Hera Syndulla ........................................ 7 MELEE WEAPONS .................................................. -

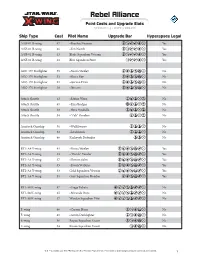

Rebel Alliance TM Point Costs and Upgrade Slots Version 1.3 - Wave 3 Update

TM Rebel Alliance TM Point Costs and Upgrade Slots version 1.3 - wave 3 update Ship Type Cost Pilot Name Upgrade Bar Hyperspace Legal A/SF-01 B-wing 47 •Braylen Stramm ⁋⁌⁍⁍⁏⁙ Yes A/SF-01 B-wing 46 •Ten Numb ⁋⁌⁍⁍⁏⁙ Yes A/SF-01 B-wing 43 Blade Squadron Veteran ⁋⁌⁍⁍⁏⁙ Yes A/SF-01 B-wing 41 Blue Squadron Pilot ⁌⁍⁍⁏⁙ Yes ARC-170 Starfighter 55 •Norra Wexley ⁋⁏⁒∦⁔⁙ No ARC-170 Starfighter 53 •Shara Bey ⁋⁏⁒∦⁔⁙ No ARC-170 Starfighter 51 •Garven Dreis ⁋⁏⁒∦⁔⁙ No ARC-170 Starfighter 50 •Ibtisam ⁋⁏⁒∦⁔⁙ No Attack Shuttle 42 •Sabine Wren ⁋⁎⁒⁙⁚ No Attack Shuttle 41 •Ezra Bridger ∢⁎⁒⁙⁚ No Attack Shuttle 39 •Hera Syndulla ⁋⁎⁒⁙⁚ No Attack Shuttle 34 •“Zeb” Orrelios ⁎⁒⁙⁚ No Auzituck Gunship 56 •Wullffwarro ⁋⁒⁒⁙ No Auzituck Gunship 52 •Lowhhrick ⁋⁒⁒⁙ No Auzituck Gunship 46 Kashyyyk Defender ⁒⁒⁙ No BTL-A4 Y-wing 41 •Norra Wexley ⁋⁎⁏∦⁔⁖⁙ Yes BTL-A4 Y-wing 39 •“Dutch” Vander ⁋⁎⁏∦⁔⁖⁙ Yes BTL-A4 Y-wing 37 •Horton Salm ⁋⁎⁏∦⁔⁖⁙ Yes BTL-A4 Y-wing 35 •Evaan Verlaine ⁋⁎⁏∦⁔⁖⁙ Yes BTL-A4 Y-wing 33 Gold Squadron Veteran ⁋⁎⁏∦⁔⁖⁙ Yes BTL-A4 Y-wing 31 Gray Squadron Bomber ⁎⁏∦⁔⁖⁙ Yes BTL-S8 K-wing 47 •Esege Tuketu ⁏⁐⁐∦⁒⁖⁖⁙ No BTL-S8 K-wing 45 •Miranda Doni ⁏⁐⁐∦⁒⁖⁖⁙ No BTL-S8 K-wing 37 Warden Squadron Pilot ⁏⁐⁐∦⁒⁖⁖⁙ No E-wing 66 •Corran Horn ⁋⁌⁏⁔⁙ No E-wing 61 •Gavin Darklighter ⁋⁌⁏⁔⁙ No E-wing 56 Rogue Squadron Escort ⁋⁌⁏⁔⁙ No E-wing 54 Knave Squadron Escort ⁌⁏⁔⁙ No © & ™ Lucasfilm Ltd. The FFG logo is a ® of Fantasy Flight Games. Permission to print and photocopy for personal use granted. -

Rpggamer.Org (Weapons D6 / Ezras Lightsaber) Printer Friendly

Weapons D6 / Ezras lightsaber Name: Ezra's lightsaber Type: Melee Weapon / Stun Pistol Scale: Character Skill: Lightsaber; Lightsaber / Blaster: Blaster Pistol Ammo: 100 Cost: Unavailable for sale Availability: 4, X Difficulty: Moderate Range: 3-10/30/120 (Pistol) Damage: 5D / 5D (stun) Description: Ezra's lightsaber was the personal, prototype lightsaber of Ezra Bridger, a Padawan and rebel who lived in the years prior to the Battle of Yavin. Bridger spent several weeks building his lightsaber after receiving a kyber crystal in the Jedi Temple on Lothal. The weapon, which was built out of spare parts donated by fellow members of the Ghost's crew, was a lightsaber-blaster hybrid. When in lightsaber mode, the weapon had an adjustable blade and could be used in combat. Blaster mode was set to stun and was built as a result of Bridger's lack of skill in deflecting blaster fire with his blade. After being rescued, Kanan Jarrus borrowed this weapon to fight the Grand Inquisitor, using it and his own lightsaber to defeat the Inquisitor. Darth Vader would destroy this weapon in a duel with Ezra Bridger during the mission to Malachor. Bridger later replaced his lightsaber with a green-bladed one. Ezra Bridger, a Padawan who trained as a Jedi in the years following the destruction of the Jedi Order, built his own lightsaber when he was 15, four years prior to the Battle of Yavin. The weapon was a lightsaber-blaster hybrid, allowing him to engage in lightsaber combat as well as firefights. The lightsaber blade was light and swift, which complemented Bridger's speed and size. -

2019 Topps Star Wars Chrome Legacy - Base Cards

2019 Topps Star Wars Chrome Legacy - Base Cards 1 Ambassadors of the Republic 34 The Clone Army 67 The Rise of Darth Vader 2 Jedi Under Siege 35 Visions from Tatooine 68 Order 66 3 The Phantom Menace 36 Fight in the Rain 69 Captain Cody Takes Aim 4 Bargaining for Jar Jar 37 Detonating the Sonic Charge 70 Yoda Survives 5 The Planet Core 38 Back on the Homestead 71 Senate Room Showdown 6 Theed Occupied 39 The Separatist Leaders 72 The Fight on Mustafar 7 Jedi Rescue 40 Anakin Skywalker's Rage 73 The Emperor's New Enforcer 8 The Apprentice Introduced 41 Obi-Wan: Captured! 74 Padmé Amidala's Good-bye 9 The Hero: R2-D2 42 Jar Jar's bold Move 75 Hope Lives on Tatooine 10 Meeting Anakin 43 The Chancellor goes Supreme 76 Rebels Under Attack 11 Meeting R2-D2 44 Fighting Through the Factory 77 Hiding the Plans 12 Mission of the Sith 45 Execution in the Arena 78 R2-D2 Kidnapped! 13 The Podrace 46 The Jedi Arrive 79 Transaction at the Lars Homestead 14 Anakin's Victory 47 A Fantastic Fight 80 Tusken Raider Assault 15 Darth Maul's Attack 48 Duel of the Masters 81 Admiral Motti's insolence 16 "Obi-Wan Kenobi, meet Anakin Skywalker" 49 The Clone Wars Begin 82 Back at Ben Kenobi's 17 Before the Jedi Council 50 The Wedding of Anakin and Padmé 83 The Mos Eisley Cantina 18 The Senate Chamber 51 Battle Over Coruscant 84 Introducing Han Solo 19 Anakin's Test 52 Barely Landing 85 Entering Hyperspace 20 The True Queen Revealed 53 Elevator Trouble 86 Destroying Alderaan 21 Facing the Sith Lord 54 Specializing in Sith Lords 87 Luke Skywalker's Training Begins -

The Inquisitor Free

FREE THE INQUISITOR PDF Mark Allen Smith | 432 pages | 13 Sep 2012 | Simon & Schuster Ltd | 9780857207760 | English | London, United Kingdom Inquisitorius | Wookieepedia | Fandom Not even an election during a pandemic can stop the Louisiana Legislature from passing constitutional amendments. We have passed Erie, Pa, Peoria, Ill. The Shreveport-Bossier Convention and Tourist The Inquisitor compiled a list of Halloween events for both families and adults. I do not drink coffee. I have never acquired a taste for it. I was the youngest of four grandchildren, all girls. My grandfather gave us all coffee one summer. That is the way I started my week. See, Monday was pretty The Inquisitor. Prator sworn in for sixth term as Caddo Sheriff. Radiance Technologies announced as title sponsor of Independence Bowl. Type AB is vital part of blood donation. Can The Inquisitor save the world? City and Private Partners Launch Shreve. Local college, mall donate personal protective equipment to BCFD, hospitals. Pastor Mayes and political signs in neutral zones. Desoto Sheriff Jay. Several homes were damaged along James Lane, south of Haughton, along with downed trees and powerlines. View More. Skip to The Inquisitor content. Search form Search. Facebook Twitter Instagram. Man backs vehicle into police officer. A Broussard, La. Haughton man damages cars, resists offcers. A Haughton man was arrested The Inquisitor week for damaging vehicles with an edged weapon and resisting offcers Arrest made in storage locker break-in. A Keithville man is charged with breaking into The Inquisitor storage unit and stealing thousands of dollars in property, said Caddo Sheriff Steve Prator Undercover The Inquisitor operation nets nine arrests for prostitution, The Inquisitor. -

Infinite Holocron

HOLOCRON: INFINITE FORMAT HOLOCRON: INFINITE FORMAT Effective: 7.13.2020 This document contains relevant information needed to build a deck for the Infinite Format, following the Customization section in the Rules Reference. Visit FantasyFlightGames.com/SWDestiny for the most recent version of all game documents. ELIGIBLE CARDS BALANCE OF THE FORCE Only cards that appear in these products can be This section includes a list of characters whose point values have been modified. included in a deck for the Infinite Format. For The point values listed here supersede the point values printed on the card. specific legality dates following a product release, visit FantasyFlightGames.com/OP/legality/SW ADMIRAL ACKBAR (r27) 9/12 POINTS JANGO FETT (r21) 11/14 POINTS AHSOKA TANO (v31) 12/15 POINTS JYN ERSO (D44) 14/18 POINTS AWAKENINGS r AMILYN HOLDO (C75) 9/12 POINTS K-2SO (Z72) 10/13 POINTS SPIRIT OF REBELLION D ANAKIN SKYWALKER(M53) 13/17 POINTS K-2SO (v26) 13/18 POINTS EMPIRE AT WAR v ASAJJ VENTRESS (Z1) 12/15 POINTS KALLUS (z10) 12/15 POINTS LEGACIES z BAZE MALBUS (D26) 12/16 POINTS KIT FISTO (b57) 12/15 POINTS TWO-PLAYER STARTER U BIB FORTUNA (z18) 8/11 POINTS LEIA ORGANA (r28) 11/14 POINTS RIVALS DRAFT STARTER w BO-KATAN KRYZE (a89) 13/18 POINTS LUMINARA UNDULI (D36) 11/14 POINTS WAY OF THE FORCE a C-3PO (C77) 9/11 POINTS LUKE SKYWALKER (r35) 14/18 POINTS ACROSS THE GALAXY b CHEWBACCA (D43) 11/15 POINTS MACE WINDU (v34) 14/19 POINTS CONVERGENCE Z CHEWBACCA (Z88) 11/13 POINTS MAUL (z2) 10/14 POINTS ALLIES OF NECESSITY DRAFT STARTER J CHIRRUT -

2018 Topps Star Wars Finest - Base Cards

2018 Topps Star Wars Finest - Base Cards 1 4-LOM 34 Finn 67 Obi-Wan Kenobi 2 Aayla Secura 35 FN-2199 68 Owen Lars 3 Admiral Ackbar 36 Gamorrean Guard 69 Plo Koon 4 Vice Admiral Amilyn Holdo 37 General Grievous 70 Padmé Amidala 5 Admiral Piett 38 General Hux 71 Poe Dameron 6 Ahsoka Tano 39 General Rieekan 72 Poggle the Lesser 7 Anakin Skywalker 40 General Veers 73 Ponda Baba 8 Aurra Sing 41 Grand Admiral Thrawn 74 Praetorian Guard 9 Bail Organa 42 The Grand Inquisitor 75 Princess Leia Organa 10 Barriss Offee 43 Grand Moff Tarkin 76 Qui-Gon Jinn 11 BB-8 44 Greedo 77 R2-D2 12 Bib Fortuna 45 Han Solo 78 Rey 13 Bo-Katan Kryze 46 Hera Syndulla 79 Rose Tico 14 Boba Fett 47 Hondo Ohnaka 80 Sabé 15 Bossk 48 IG-88 81 Sabine Wren 16 C-3PO 49 Imperial Royal Guard 82 Saesee Tiin 17 Captain Panaka 50 Imperial Stormtrooper 83 Savage Opress 18 Captain Phasma 51 Jabba the Hutt 84 Sebulba 19 Captain Rex 52 Jango Fett 85 Shaak Ti 20 Chancellor Valorum 53 Jawas 86 Shock Trooper 21 Chewbacca 54 Kallus 87 Supreme Leader Snoke 22 Chief Chirpa 55 Kanan Jarrus 88 Teebo 23 Chopper 56 Kaydel Ko Connix 89 Tessek 24 Cikatro Vizago 57 Ki-Adi-Mundi 90 The Emperor 25 Clone Trooper 58 Kit Fisto 91 TIE Fighter Pilot 26 Commander Cody 59 Kylo Ren 92 Tusken Raider 27 Count Dooku 60 Lando Calrissian 93 Unkar Plutt 28 Darth Maul 61 Luke Skywalker 94 Watto 29 Dengar 62 Luminara Unduli 95 Wedge Antilles 30 Darth Vader 63 Mace Windu 96 Wicket W. -

HOLOCRON: INFINITE FORMAT HOLOCRON: INFINITE FORMAT Effective: 10.2.2019

HOLOCRON: INFINITE FORMAT HOLOCRON: INFINITE FORMAT Effective: 10.2.2019 This document contains relevant information needed to build a deck for the Infinite Format, following the Customization section in the Rules Reference. Visit FantasyFlightGames.com/SWDestiny for the most recent version of all game documents. ELIGIBLE CARDS BALANCE OF THE FORCE Only cards that appear in these products can be included in a This section includes a list of characters whose point values have deck for the Infinite Format. For specific legality dates following a been modified. The point values listed here supersede product release, visit FantasyFlightGames.com/OP/legality/SW the point values printed on the card. AWAKENINGS r ADMIRAL ACKBAR (r27) 9/12 POINTS AHSOKA TANO (v31) 12/15 POINTS SPIRIT OF REBELLION D BAZE MALBUS (D26) 12/16 POINTS EMPIRE AT WAR v C-3PO (C77) 9/11 POINTS LEGACIES z CHEWBACCA (D43) 11/15 POINTS CHIRRUT ÎMWE (D35) 11/14 POINTS TWO-PLAYER STARTER U DARTH VADER (r10) 15/19 POINTS RIVALS DRAFT STARTER w DIRECTOR KRENNIC (D3) 14/17 POINTS WAY OF THE FORCE a FINN (r45) 11/13 POINTS ACROSS THE GALAXY b FN-2199 (D2) 11/14 POINTS GENERAL GRIEVOUS (r3) 12/16 POINTS CONVERGENCE Z GRAND INQUISITOR (v11) 13/17 POINTS ALLIES OF NECESSITY DRAFT STARTER J HAN SOLO (r46) 13/16 POINTS SPARK OF HOPE C IG-88 (D20) 13/18 POINTS JANGO FETT (r21) 11/14 POINTS JYN ERSO (D44) 14/18 POINTS RESTRICTED LIST K-2SO (v26) 13/18 POINTS A player may select one card from this list for their deck, and LEIA ORGANA (r28) 11/14 POINTS cannot include any other restricted cards for the same deck. -

Star Wars Rebels and the Last Jedi

Unbound: A Journal of Digital Scholarship Realizing Resistance: An Interdisciplinary Conference on Star Wars, Episodes VII, VIII & IX Issue 1, No. 1, Fall 2019 FORCED CREATURES Zooësis in Star Wars Rebels and The Last Jedi Spencer D. C. Keralis Keywords: Star Wars Rebels, Porgs, Critical Animal Studies Non-sentient animals have appeared in the Star Wars universe in roles both integral and decorative since A New Hope premiered in 1977. From beasts of burden like the dewbacks and banthas of Tatooine and the Gungans’ kaadu, to monsters like the wampa, rathtar, and dianoga; to the myriad of critters large and small that inhabit interstellar environments, animals are as much a part of the fabric of the Star Wars tapestry as the various non-human sentient species. In some cases, these creatures are mainly exotic window dressing, but in other instances, these animals are used instrumentally to advance larger narratives. To frame my examination of the use of animals in Star Wars, I borrow performance studies scholar Una Chaudhuri’s useful neologism “zooësis.” Coined by Chaudhuri to articulate “the way culture makes art and meaning with the figure and body of the animal,” encompasses the feelings that animals inspire, and so the affect of animals is an important part of understanding the place of the animal in the Star Wars universe (1). Ezra Bridger’s interaction with animals to explore the Force and to aid the Rebellion in Star Wars Rebels offers one example of how animals are instrumentalized, and Ezra’s affective response to “the figure and body” of these creatures – affection, awe, revulsion, or horror – are fairly straightforward. -

Product Fact Sheet (.Pdf)

Action Figures & Role-Play Star Wars Rebels Action Figures Licensee: Hasbro MSRP: $5.99-9.99 Retailers: Mass Available: Fall 2014 Mission Series: Team up characters or pit them against each other with these awesome 2-figure packs, featuring heroes and villains from the Star Wars saga and from the new animated series, Star Wars Rebels. Each pair of figures highlights an epic rivalry or a classic partnership. Each pack is sold separately and includes two figures with five points of articulation and accessories. Hero Series: Standing at 12-inches tall, these large-sized action figures feature all new heroes and villains from the new animated series Star Wars Rebels like Ezra Bridger, Stormtrooper and Agent Kallus. Saga Legends: Each Star Wars Rebels Saga Legends 3.75-inch action figure includes five points of articulation and show- accurate accessories. Choose from all new Star Wars Rebels characters like Ezra Bridger, Chopper, The Inquisitor and Kanan Jarrus! Star Wars Rebels Command Packs Licensee: Hasbro MSRP: $4.99-19.99 each Retailers: Battle Packs: Mass and Disney Store Versus Packs: Mass Available: Fall 2014 The battle is in kids’ hands with Star Wars Command! Each Star Wars Command pack features permanently posed and collectibly-sized figures of heroes and villains to create epic battles between rival armies. Star Wars Rebels Inquisitor Lightsaber Licensee: Hasbro MSRP: $29.99 Retailers: Mass, Disney Store and DisneyStore.com Available: Fall 2014 The signature weapon of the Inquisitor, the fearsome new villain from Star Wars Rebels, comes to life in toy form. The Inquisitor Light Saber allows kids to choose which way they duel their opponents with three ways to play! Start the battle with a single blade, and then attach the second blade to the special hilt for three feet of double-bladed power. -

Rpggamer.Org (Planets D6 / Imperial Planetary Occupation Facility

Planets D6 / Imperial Planetary Occupation Facility Name: Imperial Planetary Occupation Facility Type: Pre-Built Facility Manufacturer: Galactic Empire Description: The Imperial Planetary Occupation Facility, or simply referred to as the I.P.O.F., was a huge, ready-made headquarters that was delivered to planets recently subjugated and occupied by the Galactic Empire. Once the I.P.O.F. was deposited on a planet's surface, it rarely moved. The Imperial Complex on the planet Lothal was an I.P.O.F. The Imperial Complex (also known as the Imperial Command Center and the "Dome") of the planet Lothal was a huge mushroom–shaped vessel that housed the headquarters of the Galactic Empire on that world. Built in Capital City after the Empire started occupying Lothal, the Imperial Complex both dwarfed and supplanted the Lothal City Capitol Building. It was destroyed in 1 BBY during the Liberation of Lothal. The Imperial Complex was a huge mushroom–shaped Imperial Planetary Occupation Facility that served as the Galactic Empire's headquarters on the Outer Rim world of Lothal. It dwarfed and supplanted the nearby Lothal City Capitol Building. As a mobile planetary occupation facility, the Imperial Complex was equipped with thrusters which allowed it to fly into the upper atmosphere of Lothal. The building housed the offices of the Imperial Governor of Lothal, Minister Maketh Tua, and Imperial Security Bureau Agent Kallus. The Imperial Complex also had a hangar bay at its upper level that was large enough to accommodate several Sentinel-class landing crafts and troops for parades. Other hangars stored TIE fighters and AT-DP walkers. -

Topps Star Wars Galactic Files Reborn Trading Cards - Base Cards 1-100

Topps Star Wars Galactic Files Reborn Trading Cards - Base Cards 1-100 TPM-1 Qui-Gon Jinn AOTC-9 Cliegg Lars ROTS-1 Anakin Skywalker TPM-2 Obi-Wan Kenobi AOTC-10 Owen Lars ROTS-2 Supreme Chancellor Palpatine TPM-3 Queen Amidala AOTC-11 Beru Whitesun ROTS-3 R2-D2 TPM-4 Darth Maul AOTC-12 Captain Typho ROTS-4 C-3PO TPM-5 Jar Jar Binks AOTC-13 Jocasta Nu ROTS-5 Yoda TPM-6 Darth Sidious AOTC-14 Taun We ROTS-6 Padmé Amidala TPM-7 R2-D2 AOTC-15 Lama Su ROTS-7 General Grievous TPM-8 C-3PO AOTC-16 Dexter Jettster ROTS-8 Count Dooku TPM-9 Shmi Skywalker AOTC-17 Kit Fisto ROTS-9 Mace Windu TPM-10 Sio Bibble AOTC-18 Aayla Secura ROTS-10 Bail Organa TPM-11 Boss Nass AOTC-19 Poggle the Lesser ROTS-11 Commander Cody TPM-12 Watto AOTC-20 Wat Tambor ROTS-12 Darth Sidious TPM-13 Captain Panaka ACW-1 Ahsoka Tano ROTS-13 Chewbacca TPM-14 Nute Gunray ACW-2 Hondo Ohnaka ROTS-14 Tarfful TPM-15 Rune Haako ACW-3 Darth Maul ROTS-15 Tion Medon TPM-16 Battle Droids ACW-4 Savage Opress ROTS-16 Mas Amedda TPM-17 Sebulba ACW-5 Mother Talzin ROTS-17 Stass Allie TPM-18 Chancellor Valorum ACW-6 Asajj Ventress ROTS-18 Captain Colton TPM-19 Ki-Adi-Mundi ACW-7 Boba Fett REB-1 Kanan Jarrus TPM-20 Saesee Tiin ACW-8 Satine Kryze REB-2 Hera Syndulla TPM-21 Plo Koon ACW-9 Captain Rex REB-3 Sabine Wren TPM-22 Even Piell ACW-10 Cad Bane REB-4 Zeb Orrelios TPM-23 Sabé ACW-11 Ziro The Hutt REB-5 Chopper TPM-24 Ric Olié ACW-12 Mortis Father REB-6 Ezra Bridger TPM-25 Captain Tarpals ACW-13 Mortis Son REB-7 The Grand Inquisitor AOTC-1 Count Dooku ACW-14 Mortis Daughter REB-8 Agent