Nevada Wildlife Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Arctic Nation a U.S

Connecting the United States to the Arctic OUR ARCTIC NATION A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative Cover Photo: Cover Photo: Hosting Arctic Council meetings during the U.S. Chairmanship gave the United States an opportunity to share the beauty of America’s Arctic state, Alaska—including this glacier ice cave near Juneau—with thousands of international visitors. Photo: David Lienemann, www. davidlienemann.com OUR ARCTIC NATION Connecting the United States to the Arctic A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Alabama . .2 14 Illinois . 32 02 Alaska . .4 15 Indiana . 34 03 Arizona. 10 16 Iowa . 36 04 Arkansas . 12 17 Kansas . 38 05 California. 14 18 Kentucky . 40 06 Colorado . 16 19 Louisiana. 42 07 Connecticut. 18 20 Maine . 44 08 Delaware . 20 21 Maryland. 46 09 District of Columbia . 22 22 Massachusetts . 48 10 Florida . 24 23 Michigan . 50 11 Georgia. 26 24 Minnesota . 52 12 Hawai‘i. 28 25 Mississippi . 54 Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. Photo: iStock.com 13 Idaho . 30 26 Missouri . 56 27 Montana . 58 40 Rhode Island . 84 28 Nebraska . 60 41 South Carolina . 86 29 Nevada. 62 42 South Dakota . 88 30 New Hampshire . 64 43 Tennessee . 90 31 New Jersey . 66 44 Texas. 92 32 New Mexico . 68 45 Utah . 94 33 New York . 70 46 Vermont . 96 34 North Carolina . 72 47 Virginia . 98 35 North Dakota . 74 48 Washington. .100 36 Ohio . 76 49 West Virginia . .102 37 Oklahoma . 78 50 Wisconsin . .104 38 Oregon. 80 51 Wyoming. .106 39 Pennsylvania . 82 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE AN ARCTIC NATION? oday, the Arctic region commands the world’s attention as never before. -

Mammals of the California Desert

MAMMALS OF THE CALIFORNIA DESERT William F. Laudenslayer, Jr. Karen Boyer Buckingham Theodore A. Rado INTRODUCTION I ,+! The desert lands of southern California (Figure 1) support a rich variety of wildlife, of which mammals comprise an important element. Of the 19 living orders of mammals known in the world i- *- loday, nine are represented in the California desert15. Ninety-seven mammal species are known to t ':i he in this area. The southwestern United States has a larger number of mammal subspecies than my other continental area of comparable size (Hall 1981). This high degree of subspeciation, which f I;, ; leads to the development of new species, seems to be due to the great variation in topography, , , elevation, temperature, soils, and isolation caused by natural barriers. The order Rodentia may be k., 2:' , considered the most successful of the mammalian taxa in the desert; it is represented by 48 species Lc - occupying a wide variety of habitats. Bats comprise the second largest contingent of species. Of the 97 mammal species, 48 are found throughout the desert; the remaining 49 occur peripherally, with many restricted to the bordering mountain ranges or the Colorado River Valley. Four of the 97 I ?$ are non-native, having been introduced into the California desert. These are the Virginia opossum, ' >% Rocky Mountain mule deer, horse, and burro. Table 1 lists the desert mammals and their range 1 ;>?-axurrence as well as their current status of endangerment as determined by the U.S. fish and $' Wildlife Service (USWS 1989, 1990) and the California Department of Fish and Game (Calif. -

California Vegetation Map in Support of the DRECP

CALIFORNIA VEGETATION MAP IN SUPPORT OF THE DESERT RENEWABLE ENERGY CONSERVATION PLAN (2014-2016 ADDITIONS) John Menke, Edward Reyes, Anne Hepburn, Deborah Johnson, and Janet Reyes Aerial Information Systems, Inc. Prepared for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife Renewable Energy Program and the California Energy Commission Final Report May 2016 Prepared by: Primary Authors John Menke Edward Reyes Anne Hepburn Deborah Johnson Janet Reyes Report Graphics Ben Johnson Cover Page Photo Credits: Joshua Tree: John Fulton Blue Palo Verde: Ed Reyes Mojave Yucca: John Fulton Kingston Range, Pinyon: Arin Glass Aerial Information Systems, Inc. 112 First Street Redlands, CA 92373 (909) 793-9493 [email protected] in collaboration with California Department of Fish and Wildlife Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program 1807 13th Street, Suite 202 Sacramento, CA 95811 and California Native Plant Society 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento, CA 95816 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this project was provided by: California Energy Commission US Bureau of Land Management California Wildlife Conservation Board California Department of Fish and Wildlife Personnel involved in developing the methodology and implementing this project included: Aerial Information Systems: Lisa Cotterman, Mark Fox, John Fulton, Arin Glass, Anne Hepburn, Ben Johnson, Debbie Johnson, John Menke, Lisa Morse, Mike Nelson, Ed Reyes, Janet Reyes, Patrick Yiu California Department of Fish and Wildlife: Diana Hickson, Todd Keeler‐Wolf, Anne Klein, Aicha Ougzin, Rosalie Yacoub California -

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

Josie Pearl, Prospector on Nevada's Black Rock Desert

JUNE, 1962 40c • • • • . Author's car crossing the playa of Black Rock Desert in northwestern Nevada. On Black Rock Desert Trails When Dora Tucker and Nell Murbarger first began exploring the Black Rock country in northwestern Nevada they did not realize what a high, wide and wild country it was. On the Black Rock a hundred miles doesn't mean a thing. In the 10,000 square miles of this desert wasteland there isn't a foot of pavement nor a mile of railroad— neither gasoline station nor postoffice. Antelopes out-number human beings fifty to one. There's plenty of room here for exploring. By NELL MURBARGER Photographs by the author Map by Norton Allen S AN illustration of what the want to! Ain't nothin' there!" is known as "the Black Rock country," Black Rock country affords Thanking him, we accepted his re- the desert from which it derives its in the way of variety and con- port as a favorable omen and headed name actually is a stark white alkali trast, we made a J 50-mile loop trip out into the desert. Almost invariably playa, averaging a dozen miles in out of Gerlach last June. Our previous we find our best prowling in places width and stretching for 100 miles exploring of the region had been mostly where folks have told us there "ain't from Gerlach to Kings River. Merging in the northern and eastern sections, nothin'." imperceptibly with the Black Rock on so we hadn't the slightest idea of what Rising precipitously from the dead the southwest is the section known as we might find in the southern part. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement and Proposed Land-Use Plan

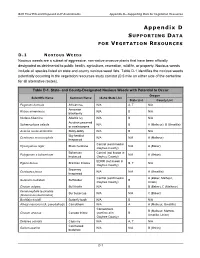

B2H Final EIS and Proposed LUP Amendments Appendix D—Supporting Data for Vegetation Resources Appendix D SUPPORTING DATA FOR VEGETATION RESOURCES D . 1 N O X I O U S W EEDS Noxious weeds are a subset of aggressive, non-native invasive plants that have been officially designated as detrimental to public health, agriculture, recreation, wildlife, or property. Noxious weeds include all species listed on state and county noxious weed lists. Table D-1 identifies the noxious weeds potentially occurring in the vegetation resources study corridor (0.5 mile on either side of the centerline for all alternative routes). Table D-1. State- and County-Designated Noxious Weeds with Potential to Occur Oregon Scientific Name Common Name Idaho State List State List County List Peganum harmala African rue N/A A, T N/A Armenian Rubus armeniacus N/A B N/A blackberry Hedera hibernica Atlantic Ivy N/A B N/A Austrian peaweed Sphaerophysa salsula N/A B A (Malheur), B (Umatilla) or swainsonpea Acaena novae-zelandiae Biddy-biddy N/A B N/A Big-headed Centaurea macrocephala N/A N/A A (Malheur) knapweed Control (confirmed in Hyoscyamus niger Black henbane N/A A (Baker) Owyhee County) Bohemian Control (not known in Polygonum x bohemicum N/A A (Union) knotweed Owyhee County) EDRR (not known in Egeria densa Brazilian Elodea B, T N/A Owyhee County) Brownray Centaurea jacea N/A N/A A (Umatilla) knapweed Control (confirmed in A (Baker, Malheur, Solanum rostratum Buffalobur B Owyhee County) Union) Cirsium vulgare Bull thistle N/A B B (Baker), C (Malheur) Ceratocephala testiculata Bur buttercup N/A N/A C (Baker) (Ranunculus testiculatus) Buddleja davidii Butterfly bush N/A B N/A Alhagi maurorum (A. -

Too Wild to Drill A

TOO WILD TO DRILL A The connection between people and nature runs deep, and the sights, sounds and smells of the great outdoors instantly remind us of how strong that connection is. Whether we’re laughing with our kids at the local fishing hole, hiking or hunting in the backcountry, or taking in the view at a scenic overlook, we all share a sense of wonder about what the natural world has to offer us. Americans around the nation are blessed with incredible wildlands out our back doors. The health of our public lands and wild places is directly tied to the health of our families, communities and economy. Unfortunately, our public lands and clean air and water are under attack. The Trump administration and some in Congress harbor deep ties to fossil fuel and mining interests, and today, resource extraction lobbyists see an unprecedented opportunity to open vast swaths of our public lands. Recent proposals to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling and shrink or eliminate protected lands around the country underscore how serious this threat is. Though some places are appropriate for responsible energy development, the current agenda in Washington, D.C. to aggressively prioritize oil, gas and coal production at the expense of all else threatens to push drilling and mining deeper into our wildest forests, deserts and grasslands. Places where families camp and hike today could soon be covered with mazes of pipelines, drill rigs and heavy machinery, or contaminated with leaks and spills. This report highlights 15 American places that are simply too important, too special, too valuable to be destroyed for short-lived commercial gains. -

Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks

B L M U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks PREPARING OFFICE U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management 3900 E. Idaho St. Elko, NV 89801 Decision Record - Memorandum Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Prepared by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Elko, NV This page intentionally left blank Decision Record - Memorandum iii Table of Contents _1. Owyhee Desert Sagebrush Focal Area Fuel Breaks Decision Record Memorandum ....... 1 _1.1. Proposed Decision .......................................................................................................... 1 _1.2. Compliance ..................................................................................................................... 6 _1.3. Public Involvement ......................................................................................................... 7 _1.4. Rationale ......................................................................................................................... 7 _1.5. Authority ......................................................................................................................... 8 _1.6. Provisions for Protest, Appeal, and Petition for Stay ..................................................... 9 _1.7. Authorized Officer .......................................................................................................... 9 _1.8. Contact Person ............................................................................................................... -

Growth Curve of White-Tailed Antelope Squirrels from Idaho

Western Wildlife 6:18–20 • 2019 Submitted: 24 February 2019; Accepted: 3 May 2019. GROWTH CURVE OF WHITE-TAILED ANTELOPE SQUIRRELS FROM IDAHO ROBERTO REFINETTI Department of Psychological Science, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho 83725, email: [email protected] Abstract.—Daytime rodent trapping in the Owyhee Desert of Idaho produced a single diurnal species: the White-tailed Antelope Squirrel (Ammospermophilus leucurus). I found four females that were pregnant and took them back to my laboratory to give birth and I raised their litters in captivity. Litter size ranged from 10 to 12 pups. The pups were born weighing 3–4 g, with purple skin color and with the eyes closed. Pups were successfully weaned at 60 d of age and approached the adult body mass of 124 g at 4 mo of age. Key Words.—Ammospermophilus leucurus; Great Basin Desert; growth; Idaho; Owyhee County The White-tailed Antelope Squirrel (Ammo- not differ significantly (t = 0.715, df = 10, P = 0.503). spermophilus leucurus; Fig. 1) is indigenous to a large After four months in the laboratory (after parturition and segment of western North America, from as far north lactation for the four pregnant females), average body as southern Idaho and Oregon (43° N) to as far south mass stabilized at 124 g (106–145 g). as the tip of the Baja California peninsula (23° N; Belk The four pregnant females were left undisturbed and Smith 1991; Koprowski et al. 2016). I surveyed a in individual polypropylene cages with wire tops (36 small part of the northernmost extension of the range cm length, 24 cm width, 19 cm height). -

Burning Man Geology Black Rock Desert.Pdf

GEOLOGY OF THE BLACK ROCK DESERT By Cathy Busby Professor of Geology University of California Santa Barbara http://www.geol.ucsb.edu/faculty/busby BURNING MAN EARTH GUARDIANS PAVILION 2012 LEAVE NO TRACE Please come find me and Iʼll give you a personal tour of the posters! You are here! In one of the most amazing geologic wonderlands in the world! Fantastic rock exposure, spectacular geomorphic features, and a long history, including: 1. PreCambrian loss of our Australian neighbors by continental rifting, * 2. Paleozoic accretion of island volcanic chains like Japan (twice!), 3. Mesozoic compression and emplacement of a batholith, 4. Cenozoic stretching and volcanism, plus a mantle plume torching the base of the continent! Let’s start with what you can see on the playa and from the playa: the Neogene to Recent geology, which is the past ~23 million years (= Ma). Note: Recent = past 15,000 years http://www.terragalleria.com Then we’ll “build” the terrane you are standing on, beginning with a BILLION years ago, moving through the Paleozoic (old life, ~540-253 Ma), Mesozoic (age of dinosaurs, ~253-65 Ma)) and Cenozoic (age of mammals, ~65 -0 Ma). Neogene to Recent geology Black Rock Playa extends 100 miles, from Gerlach to the Jackson Mountains. The Black Rock Desert is divided into two arms by the Black Rock Range, and covers 1,000 square miles. Empire (south of Gerlach)has the U.S. Gypsum mine and drywall factory (brand name “Sheetrock”), and thereʼs an opal mine at base of Calico Mtns. Neogene to Recent geology BRP = The largest playa in North America “Playa” = a flat-bottomed depression, usually a dry lake bed 3,500ʼ asl in SW, 4,000ʼ asl in N Land speed record: 1997 - supersonic car, 766 MPH Runoff mainly from the Quinn River, which heads in Oregon ~150 miles north. -

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave

North American Deserts Chihuahuan - Great Basin Desert - Sonoran – Mojave http://www.desertusa.com/desert.html In most modern classifications, the deserts of the United States and northern Mexico are grouped into four distinct categories. These distinctions are made on the basis of floristic composition and distribution -- the species of plants growing in a particular desert region. Plant communities, in turn, are determined by the geologic history of a region, the soil and mineral conditions, the elevation and the patterns of precipitation. Three of these deserts -- the Chihuahuan, the Sonoran and the Mojave -- are called "hot deserts," because of their high temperatures during the long summer and because the evolutionary affinities of their plant life are largely with the subtropical plant communities to the south. The Great Basin Desert is called a "cold desert" because it is generally cooler and its dominant plant life is not subtropical in origin. Chihuahuan Desert: A small area of southeastern New Mexico and extreme western Texas, extending south into a vast area of Mexico. Great Basin Desert: The northern three-quarters of Nevada, western and southern Utah, to the southern third of Idaho and the southeastern corner of Oregon. According to some, it also includes small portions of western Colorado and southwestern Wyoming. Bordered on the south by the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts. Mojave Desert: A portion of southern Nevada, extreme southwestern Utah and of eastern California, north of the Sonoran Desert. Sonoran Desert: A relatively small region of extreme south-central California and most of the southern half of Arizona, east to almost the New Mexico line. -

Issue 5 Spring 2015

Utah Shrubland Management Issue 5, Spring 2015 Page 1 The Spring 2015 Project Updates and Field Tour Information Newsletter highlights The field crew members on the Shrub Management Project are now preparing for our study site in Park their third summer of data collection after management actions were initiated in spring of 2013. It’s an exciting year to see the effects of herbicide, mowing,Page and 1 seed- Valley, UT. The ranch ing treatments on a diverse group of shrub, grass, and forb species. With two study where we work is sites per ranch, we can begin to compare how response to management varies be- tween closely related ecological sites. owned and operated The big news this season is that over the next two months, we’re hosting tours of our by Lance West- field sites to share our initial project results. All who are interested in rangelands— moreland and family; management practitioners, property owners, students, neighbors—are invited to come learn about the Utah shrub management project. Ecologists from USDA-ARS greasewood is the and Utah State University will be leading discussions about brush management meth- targeted shrub. ods and ecological sites at our four study locations (details below). The tours will also include presentations by state and county conser- vation agencies (DWR, NRCS, Utah State Extension) on topics such as exotic species control, juniper encroachment, seeding, and wildfire management. Lunches will be provided for tour attendees. This will be a great opportunity to learn about current approaches in range management, come join us! Photo: Beth Burritt CONTENTS 2015 Summer Field Tour Schedule Project Birdseye & Cedar Fort (Central UT) - See enclosed flyer May 20 1 Updates Targeted Shrubs: Rubber Rabbitbrush & Snakeweed Park Valley ranch: Partners: NRCS, DWR, UACD Zone 3 Overview of 2 Time: 9am — 4pm ecological sites Park Valley (North-Western UT) - See enclosed flyer June 2 Greasewood: Targeted Shrub: Black Greasewood Natural history 5 Partners: West Box Elder Coord.