Using Music to Teach Social Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Solidarity Sing-Along

Song credits: 1. We Shall Overcome adapted from a gospel song by Charles Albert Tindley, current version first published in 1947 in the People's Songs Bulletin 2. This Land is Your Land by Woody Guthrie, Wisconsin chorus by Peter Leidy 3. I'm Stickin' to the Union (also known as Union Maid) by Woody Guthrie, final updated verse added in the 1980's 4. We Shall Not Be Moved adapted from the spiritual "I shall not be moved" 5. There is Power in a Union music and lyrics by Billy Bragg 6. When We Make Peace lyrics by the Raging Grannies 7. Keep Your Eyes on the Prize lyrics by Alice Wine, based on the traditional song "Gospel Plow" 8. Solidarity Forever by Ralph Chaplin, updated verses by Steve Suffet, from the Little Red Songbook 9. Have You Been to Jail for Justice music and lyrics by Anne Feeney 10. Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me 'roun based on the spiritual “Don't You Let Nobody Turn You Around” Solidarity 11. It Isn’t Nice by Malvina Reynolds with updated lyrics by the Kissers 12. Roll the Union On Original music and lyrics by John Handcox, new lyrics by the people of Wisconsin Sing-along 13. We Are a Gentle Angry People by Holly Near We Shall Overcome 14. Which Side Are You On? Original lyrics by Florence This Land is Your Land Reece, melody from a traditional Baptist hymn, “Lay the Lily Low”, new lyrics by Daithi Wolfe I'm Stickin' to the Union 15. Scotty, We’re Comin’ for You words and music by the We Shall Not Be Moved Kissers There is Power in a Union 16. -

The Sensational 70S Long Weekend Playlist

The Sensational 70s Long Weekend Playlist Friday, 14 April 2017 6AM It's A Miracle Barry Manilow Cheeseburger In Paradise Jimmy Buffett Feelin' Stronger Every Day Chicago You Make Me Feel Brand New Stylistics Turn The Beat Around Vicki Sue Robinson I Only Have Eyes For You Art Garfunkel Beth Kiss Howzat Sherbet Fire And Rain Marcia Hines Slip Slidin' Away Paul Simon TSOP [The Sound Of Philadelphia] MFSB The Logical Song Supertramp Friday, 14 April 2017 7AM Garden Party Ricky Nelson Blame It On The Boogie Jacksons Wild World Cat Stevens Daydreamer David Cassidy Don't Let Me Be Lonely, Tonight James Taylor Hold Back The Nights Trammps Magnet And Steel Walter Egan The World’s Greatest Mum Johnny Chester Wham Bam Shang-A-Lang Silver Everybody Plays The Fool Main Ingredient You Are So Beautiful Joe Cocker Crazy Love Poco Daddy Cool Boney M Heaven On The 7th Floor Paul Nicholas Cinderella Rockafella Ann & Johnny Hawker Forever Autumn Justin Hayward Friday, 14 April 2017 8AM Train Leo Sayer A Little Bit Of Soap Paul Davis The Last Resort Eagles Could You Ever Love Me Again Gary & Dave 1 Thunder Island Jay Ferguson Let The Children Play Santana When I Kissed A Teacher Abba One Monkey Don't Stop No Show Honey Cone I'm Not In Love 10CC Wild Night Van Morrison Wig Wam Bam Sweet Papa Was A Rolling Stone Temptations Friday, 14 April 2017 9AM Another Day Paul McCartney Rocky Austin Roberts Play Mumma Play John J Francis Sing Carpenters Better Love Next Time Doctor Hook I'll Be Good For You Brothers Johnson Son Of My Father Chicory Tip Spooky Atlanta -

RAY STEVENS' Cabaray NASHVILLEPUBLIC TV 201 NEW

1. REVISION #3 3/20/2017 RAY STEVENS’ CabaRay NASHVILLEPUBLIC TV SYNDICATED EPISODES 201 - 252 PBS SHOW # GUEST(S) PERFORMANCES FEED DATE 201 Harold Bradley “Sgt. Preston of the Mounties” . NEW SHOW 7.07.2017 “Jeremiah Peabody’s Poly-Unsaturated, w.Mandy Barnett Quick Dissolving, Fast-Actin’, Pleasant Tastin’, Green and Purple Pills” .”Harry, The Hairy Ape” (RAY) “Crazy” & “I’m Confessin’” (MANDY) * 202 “Ned Nostril” (Ray) 7.14.2017 “Only You” (Ray) “Two Dozen Roses” (Shenandoah) “Sleepwalk” (A-Team) “I Want To Be Loved Like That” (Shenandoah) “Church On The Cumberland Road” (Shenandoah) * 203 Michael W. Smith “Dry Bones” (RAY) 7.21.2017 (GOSPEL THEME) “Would Jesus Wear A Rolex” (RAY) “This Ole House” (Ray) “I’ll Fly Away” (Duet w.Smitty) “Shine On Me” (SMITTY) 204 BJ Thomas ‘Hound Dog” (RAY) 7.28.2017 “Mr. Businessman” (duet w.BJ) “I Saw Elvis In A UFO” (RAY) “Rain Drops Keep Fallin’ On My Head” (chorus & verse BJ) “Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song” (BJ) * 205 Rhonda Vincent “King of the Road” (RAY) 8.04.2017 “Chug-A-Lug” (RAY) “Just A Closer Walk With Thee” (Duet w.Rhonda) “Jolene” * 206 Restless Heart “That Ole Black Magic” (RAY) 8.11.2017 Larry Steward “Spiders And Snakes” (RAY) John Dittrich “Everything Is Beautiful” (duet Paul Gregg With Restless Heart) David Innis “Bluest Eyes In Texas” (RESTLESS) Greg Jennings * 207 John Michael “Get Your Tongue Out 8.18.2017 Montgomery Of My Mouth, I’m Kissing You Goodbye” & “Retired” (RAY) “Letters From Home” & “Sold” (JOHN MICHAEL) 208 Ballie and the Boys “Little Egypt” & “Poison Ivy” (RAY) 8.25.2017 Kathie Bonagoura “(Wish I Had) A Heart of Stone” & Michael Bonagoura “House My Daddy Built” (BAILLIE) Molly Cherryholmes 2. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

Sweet at Top of the Pops

1-4-71: Presenter: Tony Blackburn (Wiped) THE SWEET – Funny Funny ELVIS PRESLEY – There Goes My Everything (video) JIMMY RUFFIN – Let’s Say Goodbye Tomorrow CLODAGH RODGERS – Jack In The Box (video) FAME & PRICE TOGETHER – Rosetta CCS – Walkin’ (video) (danced to by Pan’s People) THE FANTASTICS – Something Old, Something New (crowd dancing) (and charts) YES – Yours Is No Disgrace T-REX – Hot Love ® HOT CHOCOLATE – You Could Have Been A Lady (crowd dancing) (and credits) ........................................................................................................................................................ THIS EDITION OF TOTP IS NO LONGER IN THE BBC ARCHIVE, HOWEVER THE DAY BEFORE THE BAND RECORDED A SHOW FOR TOPPOP AT BELLEVIEW STUDIOS IN AMSTERDAM, WEARING THE SAME STAGE OUTFITS THAT THEY HAD EARLIER WORN ON “LIFT OFF”, AND THAT THEY WOULD WEAR THE FOLLOWING DAY ON TOTP. THIS IS THE EARLIEST PICTURE I HAVE OF A TV APPEARANCE. 8-4-71: Presenter: Jimmy Savile (Wiped) THE SWEET – Funny Funny ANDY WILLIAMS – (Where Do I Begin) Love Story (video) RAY STEVENS – Bridget The Midget DAVE & ANSIL COLLINS – Double Barrel (video) PENTANGLE – Light Flight JOHN LENNON & THE PLASTIC ONO BAND – Power To The People (crowd dancing) (and charts) SEALS & CROFT – Ridin’ Thumb YVONNE ELLIMAN, MURRAY HEAD & THE TRINIDAD SINGERS – Everything's All Right YVONNE ELLIMAN, MURRAY HEAD & THE TRINIDAD SINGERS – Superstar T-REX – Hot Love ® DIANA ROSS – Remember Me (crowd dancing) (and credits) ......................................................................................................................................................... -

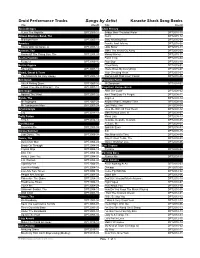

Druid Performance Tracks Karaoke

Druid Performance Tracks Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID Alicia Bridges Elvis Presley I Love The Nightlife DPT2009-14 Bridge Over Troubled Water DPT2015-15 Allman Brothers Band, The Don't DPT2015-12 Midnight Rider DPT2005-11 Early Morning Rain DPT2015-09 America Frankie And Johnny DPT2015-05 Horse With No Name, A DPT2005-12 Little Sister DPT2015-13 Animals, The Make The World Go Away DPT2015-02 House Of The Rising Sun, The DPT2005-05 Money Honey DPT2015-11 Aretha Franklin Patch It Up DPT2015-04 Respect DPT2009-10 Poor Boy DPT2015-10 Bertie Higgins Proud Mary DPT2015-01 Key Largo DPT2007-12 There Goes My Everything DPT2015-07 Blood, Sweat & Tears Your Cheating Heart DPT2015-03 You Made Me So Very Happy DPT2005-13 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' DPT2015-06 Bob Dylan Emmylou Harris Like A Rolling Stone DPT2007-10 Mr Sandman DPT2014-01 Times They Are A-Changin', The DPT2007-11 Engelbert Humperdinck Bob Seger After The Lovin' DPT2008-02 Against The Wind DPT2007-02 Am I That Easy To Forget DPT2008-11 Byrds, The Angeles DPT2008-14 Mr Bojangles DPT2007-09 Another Place, Another Time DPT2008-10 Mr Tambourine Man DPT2007-08 Last Waltz, The DPT2008-04 Crystal Gayle Love Me With All Your Heart DPT2008-12 Cry DPT2014-11 Man Without Love, A DPT2008-07 Dolly Parton Mona Lisa DPT2008-13 9 To 5 DPT2014-13 Quando, Quando, Quando DPT2008-05 Don McLean Release Me DPT2008-01 American Pie DPT2007-05 Spanish Eyes DPT2008-03 Donna Summer Still DPT2008-15 Last Dance, The DPT2009-04 This Moment In Time DPT2008-09 Doors, The Way It Used To Be, The DPT2008-08 Back Door Man DPT2004-02 Winter World Of Love DPT2008-06 Break On Through DPT2004-05 Eric Clapton Crystal Ship DPT2004-12 Cocaine DPT2005-02 End, The DPT2004-06 Fontella Bass Hello, I Love You DPT2004-07 Rescue Me DPT2009-15 L.A. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Poemm Emoir Stor Y 2 0 14

Melissa Boston poemm Number Thirteen/2014 Elya Braden Jenny Burkholder Kristi Carter Alison Chapman Melissa DeCarlo emoir Stephanie Dickinson Heather Dundas Lauren Fath Yolanda Franklin story Naoko Fujimoto Madelyn Garner Inez D. Geller Juliana Gray Mary Grover Judith O’Connell Hoyer Jessica Jacobs Carrie Jerrell Suzanne M. Levine Callie Mauldin Victoria McArtor Heal McKnight Antonya Nelson Christina Nettles Inés Orihuela Tina Parker Shobha Rao Cynthia Ryan Mia Sara Sonia Scherr Julia Shipley Hilary Sideris 2014 Susan Terris Whitnee Thorp $10.00 Julie Marie Wade Diana Wagman .. PMSpoemmemoirstory 2014number thirteen Copyright © 2014 by PMS poemmemoirstory PMS is a journal of women’s poetry, memoir, and short fiction published once a year. Subscriptions are $10 per year, $15 for two years, or $18 for three years; sample copies are $7. Unsolicited manuscripts of up to five poems or fifteen pages of prose are welcome during our reading period (January 1 through March 30), but must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for consideration. Manuscripts received at other times of the year will be returned unread. For submission guidelines and to submit online, visit us at www.pms-journal.org, or send a SASE to the address below. All rights revert to the author upon publication. Reprints are permitted with appropriate acknowledgment. Address all correspon- dence to: PMS poemmemoirstory HB 213 1530 3rd Avenue South Birmingham, AL 35294-1260 PMS poemmemoirstory is a member of the Council of Literary Maga- zines and Presses (CLMP) and the Council of Editors of Learned Journals (CELJ). Indexed by the Humanities International Index and in Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents, PMS poemmemoirstory is distributed to the trade by Ingram Periodicals, 1226 Heil Quaker Blvd., La Vergne, TN 37086-7000. -

The Journal of the Core Curriculum Volume XII Spring 2003 the Journal of the Core Curriculum

The Journal of the Core Curriculum Volume XII Spring 2003 The Journal of the Core Curriculum Volume XII Julia Bainbridge, EDITOR Zachary Bos, ART DIRECTOR Agnes Gyorfi, LAYOUT EDITORIAL BOARD Brittany Aboutaleb Kristen Cabildo Kimberly Christensen Jehae Kim Heather Levitt Nicole Loughlin Cassandra Nelson Emily Patulski Christina Wu James Johnson, DIRECTOR of the CORE CURRICULUM and FACULTY ADVISOR PUBLISHED by BOSTON UNIVERSITY at BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, in the month of MAY, 2003 My mother groan'd! my father wept. Into the dangerous world I leapt: Hapless, naked, piping loud: Like a fiend hid in a cloud. ~William Blake Copyright © MMIII by the Trustees of Boston University. Reproduction of any material contained herein without the expressed consent of the authors is strictly forbidden. Printed 2003 by Offset Prep. Inc., North Quincy, Massachusetts. Table of Contents In the Beginning 7 Stephanie Pickman Love 10 Jonathon Wooding Sans Artifice 11 Ryan Barrett A Splintering 18 Jaimee Garbacik Ripeness and Rot in Shakespeare 22 Stephen Miran Interview with the Lunatic: A Psychiatric 28 Counseling Session with Don Quixote Emily Patulski In My Mind 35 Julia Schumacher On Hope and Feathers 37 Matt Merendo Exploration of Exaltation: A Study of the 38 Methods of James and Durkheim Julia Bainbridge Today I Saw Tombstones 43 Emilie Heilig A Dangerous Journey through the Aisles of Shaw’s 44 Brianna Ficcadenti Searching for Reality: Western and East Asian 48 Conceptions of the True Nature of the Universe Jessica Elliot Journey to the Festival 56 Emilie -

Ivory Markets of Europe 23/11/2005 02:25 PM Page 1

Ivory Markets of Europe 23/11/2005 02:25 PM Page 1 Ivory Markets of Europe A survey in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK Esmond Martin and Daniel Stiles Drawings by Andrew Kamiti Published by Care for the Wild International Save the Elephants The Granary PO Box 54667, 00200 Nairobi, Kenya Tickfold Farm and Kingsfold c/o Ambrose Appelbe, 7 New Square, West Sussex RH12 3SE Lincoln’s Inn, London, WC2A 3RA UK UK 2005 ISBN 9966 - 9683 - 4 - 2 Ivory Markets of Europe 23/11/2005 02:25 PM Page 2 CONTENTS List of tables 3 Executive summary 5 Introduction 7 Methodology 8 Results 9 Germany 9 United Kingdom 29 France 45 Spain 64 Italy 78 Status of the ivory trade in Europe 90 Trends in the ivory trade in Europe 93 Discussion 96 Conclusions 99 References 102 Acknowledgements inside back cover 2 Ivory Markets of Europe 23/11/2005 02:25 PM Page 3 LIST OF TABLES Germany Table 1 Number of illegal elephant product seizures made in Germany recorded by ETIS, 1989-2003 Table 2 Number of craftsmen working in ivory in Erbach from the 1870s to 2004 Table 3 Number of ivory items seen for retail sale in Germany, September 2004 Table 4 Types of retail outlets selling ivory items in Germany, September 2004 Table 5 Ivory items for retail sale in the largest shop in Michelstadt, September 2004 Table 6 Retail prices for ivory items seen in Michelstadt, September 2004 Table 7 Retail prices for ivory items seen in Erbach, September 2004 Table 8 Number of retail outlets and ivory items in the main antique markets in Berlin, September 2004 Table 9 New (post 1989) -

Read an Excerpt

The Artist Alive: Explorations in Music, Art & Theology, by Christopher Pramuk (Winona, MN: Anselm Academic, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Christopher Pramuk. All rights reserved. www.anselmacademic.org. Introduction Seeds of Awareness This book is inspired by an undergraduate course called “Music, Art, and Theology,” one of the most popular classes I teach and probably the course I’ve most enjoyed teaching. The reasons for this may be as straightforward as they are worthy of lament. In an era when study of the arts has become a practical afterthought, a “luxury” squeezed out of tight education budgets and shrinking liberal arts curricula, people intuitively yearn for spaces where they can explore together the landscape of the human heart opened up by music and, more generally, the arts. All kinds of people are attracted to the arts, but I have found that young adults especially, seeking something deeper and more worthy of their questions than what they find in highly quantitative and STEM-oriented curricula, are drawn into the horizon of the ineffable where the arts take us. Across some twenty-five years in the classroom, over and over again it has been my experience that young people of diverse religious, racial, and economic backgrounds, when given the opportunity, are eager to plumb the wellsprings of spirit where art commingles with the divine-human drama of faith. From my childhood to the present day, my own spirituality1 or way of being in the world has been profoundly shaped by music, not least its capacity to carry me beyond myself and into communion with the mysterious, transcendent dimension of reality.