Life History Account for Desert Night Lizard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Zootaxa, a New Species of Night-Lizard of the Genus Lepidophyma

Zootaxa 1750: 59–67 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new species of night-lizard of the genus Lepidophyma (Squamata: Xantusiidae) from the Cuicatlán Valley, Oaxaca, México LUIS CANSECO-MÁRQUEZ1, GUADALUPE GUTIÉRREZ-MAYEN2 & ANDRÉS ALBERTO MENDOZA-HERNÁNDEZ1 1Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Museo de Zoología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, A.P. 70-399, C. P. 04510, México, D. F., México 2Escuela de Biología, Laboratorio de Herpetología, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, C.P. 72570, Puebla, Puebla, Méx- ico Abstract A new species of Lepidophyma from the Biosphere Reserve area of Tehuacan-Cuicatlan, Oaxaca, Mexico, is described. This new species, Lepidophyma cuicateca sp. nov., is known from two areas in the Cuicatlan Valley. Lepidophyma cuicateca sp. nov. is a member of the Lepidophyma gaigeae species Group and is characterized by its small body size, small size of tubercular body scales, poorly differentiated caudal whorls and interwhorls, and relatively large dorsal, ven- tral and gular scales. It lives in shady places, below rocks along the Apoala River, and is commonly found in plantain, sapodilla, cherimoya, mango and coffee plantations, as well as tropical deciduous forest. The description of L. cuicateca sp. nov. increases the number of species in the L. gaigeae Group to five. Key words: Squamata, Lepidophyma gaigeae Group, Lepidophyma cuicateca sp. nov., new species, Xantusiidae, Mex- ico, Oaxaca Resumen Se describe una nueva especie de Lepidophyma para la parte oaxaqueña de la reserva de la biosfera de Tehuacán- Cuicatlán. Esta especie es conocida para dos áreas de la Cañada de Cuicatlán. -

0189 Xantusia Henshawi.Pdf (296.1Kb)

189.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SAURIA: XANTUSIIDAE XANTUSIA HENSHA WI Catalogue of Am.erican Am.phihians and Reptiles. sequently (Van Denburgh, 1922) placed Z ablepsis henshavii in the synonymy ofX. henshawi Stejneger. Cope (1895b) described, LEE, JULIANC. 1976. Xantusia henshawi. but failed to name a supposedly new species of Xantusia. In a later publication (Cope, 1895c) he corrected the oversight, and named Xantusia picta. Van Denburgh (1916) synonymized Xantusia henshawi Stejneger picta with X. henshawi, and traced the complicated history of Granite night lizard the type-specimen . Xantusia henshawi Stejneger, 1893:467. Type-locality, "Witch • ETYMOLOGY.The specific epithet honors H. W. Henshaw. Creek, San Diego County, California." Holotype, U. S. Nat. According to Webb (1970), "The name bolsonae refers to the Mus. 20339, collected in May 1893 by H. W. Henshaw (Holo• geographic position of this race in a southern outlier of the type not seen by author). Bolson de Mapimi." Zablepsis henshavii: Cope, 1895a:758. See NOMENCLATURAL HISTORY. 1. Xantusia henshawi henshawi Stejnege •. Xantusia picta Cope, 1895c:859. Type-locality, "Tejon Pass, California," probably in error, corrected by Van Denburgh Xantusia henshawi Stejneger, 1893:467. See species account. Xantusia henshawi henshawi: Webb, 1970:2. First use of tri- (1916:14) to Poway, San Diego County, California. Holotype, nomial. Acad. Natur. Sci. Philadelphia 12881 (Malnate, 1971), prob• ably collected by Dr. Frank E. Blaisdell (see NOMENCLATURAL • DEFINITIONANDDIAGNOSIS. The mean snout-vent length HISTORY). in males is 56 mm., and in females 62 mm. Distinct post• • CONTENT. Two subspecies are recognized: henshawi and orbital stripes are usually absent, and the dorsal color pattern bolsonae. -

Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Herpetology Papers in the Biological Sciences 1993 Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A. Somma Florida State Collection of Arthropods, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Somma, Louis A., "Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska?" (1993). Papers in Herpetology. 11. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Herpetology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. @ o /' number , ,... :S:' .' ,. '. 1'1'13 Do Mono Li ••rel,. Occur ill 1!I! ..br .... l< .. ? by Louis A. Somma Department of- Zoology University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 Amphisbaenids, or worm lizards, are a small enigmatic suborder of reptiles (containing 4 families; ca. 140 species) within the order Squamata, which include~ the more speciose lizards and snakes (Gans 1986). The name amphisbaenia is derived from the mythical Amphisbaena (Topsell 1608; Aldrovandi 1640), a two-headed beast (one head at each end), whose fantastical description may have been based, in part, upon actual observations of living worm lizards (Druce 1910). While most are limbless and worm-like in appearance, members of the family Bipedidae (containing the single genus Sipes) have two forelimbs located close to the head. This trait, and the lack of well-developed eyes, makes them look like two-legged worms. -

Habitat Selection of the Desert Night Lizard (Xantusia Vigilis) on Mojave Yucca (Yucca Schidigera) in the Mojave Desert, California

Habitat selection of the desert night lizard (Xantusia vigilis) on Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera) in the Mojave Desert, California Kirsten Boylan1, Robert Degen2, Carly Sanchez3, Krista Schmidt4, Chantal Sengsourinho5 University of California, San Diego1, University of California, Merced2, University of California, Santa Cruz3, University of California, Davis4 , University of California, San Diego5 ABSTRACT The Mojave Desert is a massive natural ecosystem that acts as a biodiversity hotspot for hundreds of different species. However, there has been little research into many of the organisms that comprise these ecosystems, one being the desert night lizard (Xantusia vigilis). Our study examined the relationship between the common X. vigilis and the Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera). We investigated whether X. vigilis exhibits habitat preference for fallen Y. schidigera log microhabitats and what factors make certain log microhabitats more suitable for X. vigilis inhabitation. We found that X. vigilis preferred Y. schidigera logs that were larger in circumference and showed no preference for dead or live clonal stands of Y. schidigera. When invertebrates were present, X. vigilis was approximately 50% more likely to also be present. These results suggest that X. vigilis have preferences for different types of Y. schidigera logs and logs where invertebrates are present. These findings are important as they help in understanding one of the Mojave Desert’s most abundant reptile species and the ecosystems of the Mojave Desert as a whole. INTRODUCTION such as the Mojave Desert in California. Habitat selection is an important The Mojave Desert has extreme factor in the shaping of an ecosystem. temperature fluctuations, ranging from Where an animal chooses to live and below freezing to over 134.6 degrees forage can affect distributions of plants, Fahrenheit (Schoenherr 2017). -

A Pipeline for Identifying Metagenomic Sequences in Radseq Data

Natural history bycatch: a pipeline for identifying metagenomic sequences in RADseq data Iris Holmes and Alison R. Davis Rabosky Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ABSTRACT Background: Reduced representation genomic datasets are increasingly becoming available from a variety of organisms. These datasets do not target specific genes, and so may contain sequences from parasites and other organisms present in the target tissue sample. In this paper, we demonstrate that (1) RADseq datasets can be used for exploratory analysis of tissue-specific metagenomes, and (2) tissue collections house complete metagenomic communities, which can be investigated and quantified by a variety of techniques. Methods: We present an exploratory method for mining metagenomic “bycatch” sequences from a range of host tissue types. We use a combination of the pyRAD assembly pipeline, NCBI’s blastn software, and custom R scripts to isolate metagenomic sequences from RADseq type datasets. Results: When we focus on sequences that align with existing references in NCBI’s GenBank, we find that between three and five percent of identifiable double-digest restriction site associated DNA (ddRAD) sequences from host tissue samples are from phyla to contain known blood parasites. In addition to tissue samples, we examine ddRAD sequences from metagenomic DNA extracted snake and lizard hind-gut samples. We find that the sequences recovered from these samples match with expected bacterial -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

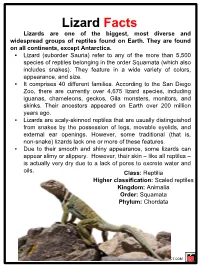

Lizard Facts Lizards Are One of the Biggest, Most Diverse and Widespread Groups of Reptiles Found on Earth

Lizard Facts Lizards are one of the biggest, most diverse and widespread groups of reptiles found on Earth. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica. ▪ Lizard (suborder Sauria) refer to any of the more than 5,500 species of reptiles belonging in the order Squamata (which also includes snakes). They feature in a wide variety of colors, appearance, and size. ▪ It comprises 40 different families. According to the San Diego Zoo, there are currently over 4,675 lizard species, including iguanas, chameleons, geckos, Gila monsters, monitors, and skinks. Their ancestors appeared on Earth over 200 million years ago. ▪ Lizards are scaly-skinned reptiles that are usually distinguished from snakes by the possession of legs, movable eyelids, and external ear openings. However, some traditional (that is, non-snake) lizards lack one or more of these features. ▪ Due to their smooth and shiny appearance, some lizards can appear slimy or slippery. However, their skin – like all reptiles – is actually very dry due to a lack of pores to excrete water and oils. Class: Reptilia Higher classification: Scaled reptiles Kingdom: Animalia Order: Squamata Phylum: Chordata KIDSKONNECT.COM Lizard Facts MOBILITY All lizards are capable of swimming, and a few are quite comfortable in aquatic environments. Many are also good climbers and fast sprinters. Some can even run on two legs, such as the Collared Lizard and the Spiny-Tailed Iguana. LIZARDS AND HUMANS Most lizard species are harmless to humans. Only the very largest lizard species pose any threat of death. The chief impact of lizards on humans is positive, as they are the main predators of pest species. -

Meet the Herps!

Science Standards Correlation SC06-S2C2-03, SC04-S4C1-04, SC05-S4C1-01, SC04-S4C1-06, SC07-S4C3-02, SC08- S4C4-01, 02&06 MEET THE HERPS! Some can go without a meal for more than a year. Others can live for a century, but not really reach a ripe old age for another couple of decades. One species is able to squirt blood from its eyes. What kinds of animals are these? They’re herps – the collective name given to reptiles and amphibians. What Is Herpetology? The word “herp” comes from the word “herpeton,” the Greek word for “crawling things.” Herpetology is the branch of science focusing on reptiles and amphibians. The reptiles are divided into four major groups: lizards, snakes, turtles, and crocodilians. Three major groups – frogs (including toads), salamanders and caecilians – make up the amphibians. A herpetologist studies animals from all seven of these groups. Even though reptiles and amphibians are grouped together for study, they are two very different kinds of animals. They are related in the sense that early reptiles evolved from amphibians – just as birds, and later mammals, evolved from reptiles. But reptiles and amphibians are each in a scientific class of their own, just as mammals are in their own separate class. One of the reasons reptiles and amphibians are lumped together under the heading of “herps” is that, at one time, naturalists thought the two kinds of animals were much more closely related than they really are, and the practice of studying them together just persisted through the years. Reptiles vs. Amphibians: How Are They Different? Many of the differences between reptiles and amphibians are internal (inside the body). -

Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles)

6-3.1 Compare the characteristic structures of invertebrate animals... and vertebrate animals (fish, amphibians, and reptiles). Also covers: 6-1.1, 6-1.2, 6-1.5, 6-3.2, 6-3.3 Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles sections Can I find one? If you want to find a frog or salamander— 1 Chordates and Vertebrates two types of amphibians—visit a nearby Lab Endotherms and Exotherms pond or stream. By studying fish, amphib- 2 Fish ians, and reptiles, scientists can learn about a 3 Amphibians variety of vertebrate characteristics, includ- 4 Reptiles ing how these animals reproduce, develop, Lab Water Temperature and the and are classified. Respiration Rate of Fish Science Journal List two unique characteristics for Virtual Lab How are fish adapted each animal group you will be studying. to their environment? 220 Robert Lubeck/Animals Animals Start-Up Activities Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles Make the following Foldable to help you organize Snake Hearing information about the animals you will be studying. How much do you know about reptiles? For example, do snakes have eyelids? Why do STEP 1 Fold one piece of paper lengthwise snakes flick their tongues in and out? How into thirds. can some snakes swallow animals that are larger than their own heads? Snakes don’t have ears, so how do they hear? In this lab, you will discover the answer to one of these questions. STEP 2 Fold the paper widthwise into fourths. 1. Hold a tuning fork by the stem and tap it on a hard piece of rubber, such as the sole of a shoe. -

Biodiversity of Amphibians and Reptiles at the Camp Cady Wildlife

Ascending and descending limbs of hydrograph Pulse flow ascending-descending limbs of hydrograph Low Peak Restora- Low Peak Pulse Low release release tion release release restoration Shape release mag- Shape mag- release Shape mag- Date and Shape mag- release de- mag- Date and Water nitude ascend- nitude (hector descend- nitude duration flow Total Low ascend- nitude (hector scend- nitude duration flow to Total Year Year Flow (m3/s) ing (m3/s) m) ing (m3/s) to base-flow days (m3/s) ing (m3/s) m) ing (m3/s) base-flow days 25 Apr-22 1995 na Pre-ROD 14 R 131 na G 27 28 May 1996 na Pre-ROD 9 R 144 na G, 1B 14 10 May-9 Jun 31 1997 na Pre-ROD 10 R 62 na G, 3B 13 2 May-2 Jul 62 1998 na Pre-ROD 47 R 192 na G 13 24 May-27 Jul 65 1999 na Pre-ROD 15 G 71 na G 13 8 May-18 Jul 72 2000 na Pre-ROD 9 R 66 na G 13 8 May-27 Jul 81 2002 normal Pre-ROD 9 R 171 59,540 G 13 27 Apr-25 Jun 28 2003 wet Pulse 9 R 74 55,272 G, 2B 12 29 Apr-22 Jul 85 13 R 51 4,194 G 12 23 Aug-18 Sep 27 2004 wet Pulse 9 R 176 80,300 G, 4B 12 4 May-22 Jul 80 16 R 48 4,465 G 14 21 Aug-14 Sep 25 2005 wet ROD 8 R, 2 B 197 79,880 G, 1B 13 27 Apr-22 Jul 87 2006 extra wet ROD 8 G, 5B 286 99,900 G, 2B 13 16 Apr-22 Jul 98 2007 dry ROD 8 R 135 55,963 G 13 25 Apr-25 Jun 62 2008 dry ROD 9 R, 1B 183 80,016 G, 3B 20 22 Apr-15 Jul 85 2009 dry ROD 8 R 125 54,952 G, 4B 12 24 Apr-6 Jul 74 2010 wet ROD 9 R 194 81,003 G, 3B 12 22 Apr-2 Aug 102 2011 wet ROD 7 R, 2B 329 89,033 G, 2B 13 26 Apr-1 Aug 98 2012 normal Pulse 9 R, 2B 172 79,819 G, 4B 13 4 Apr-26 Jul 114 13 R, 1B 39 4,811 R, 1B 13 12 Aug-20 Sep -

Class: Amphibia Amphibians Order

CLASS: AMPHIBIA AMPHIBIANS ANNIELLIDAE (Legless Lizards & Allies) CLASS: AMPHIBIA AMPHIBIANS Anniella (Legless Lizards) ORDER: ANURA FROGS AND TOADS ___Silvery Legless Lizard .......................... DS,RI,UR – uD ORDER: ANURA FROGS AND TOADS BUFONIDAE (True Toad Family) BUFONIDAE (True Toad Family) ___Southern Alligator Lizard ............................ RI,DE – fD Bufo (True Toads) Suborder: SERPENTES SNAKES Bufo (True Toads) ___California (Western) Toad.............. AQ,DS,RI,UR – cN ___California (Western) Toad ............. AQ,DS,RI,UR – cN ANNIELLIDAE (Legless Lizards & Allies) Anniella ___Red-spotted Toad ...................................... AQ,DS - cN BOIDAE (Boas & Pythons) ___Red-spotted Toad ...................................... AQ,DS - cN (Legless Lizards) Charina (Rosy & Rubber Boas) ___Silvery Legless Lizard .......................... DS,RI,UR – uD HYLIDAE (Chorus Frog and Treefrog Family) ___Rosy Boa ............................................ DS,CH,RO – fN HYLIDAE (Chorus Frog and Treefrog Family) Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs) Pseudacris (Chorus Frogs) Suborder: SERPENTES SNAKES ___California Chorus Frog ............ AQ,DS,RI,DE,RO – cN COLUBRIDAE (Colubrid Snakes) ___California Chorus Frog ............ AQ,DS,RI,DE,RO – cN ___Pacific Chorus Frog ....................... AQ,DS,RI,DE – cN Arizona (Glossy Snakes) ___Pacific Chorus Frog ........................AQ,DS,RI,DE – cN BOIDAE (Boas & Pythons) ___Glossy Snake ........................................... DS,SA – cN Charina (Rosy & Rubber Boas) RANIDAE (True Frog Family)