The Struggle with the Daemon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES in ISLAM

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES IN ISLAM Editiorial Board Baderin, Mashood, SOAS, University of London Fadil, Nadia, KU Leuven Goddeeris, Idesbald, KU Leuven Hashemi, Nader, University of Denver Leman, Johan, GCIS, emeritus, KU Leuven Nicaise, Ides, KU Leuven Pang, Ching Lin, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Platti, Emilio, emeritus, KU Leuven Tayob, Abdulkader, University of Cape Town Stallaert, Christiane, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Toğuşlu, Erkan, GCIS, KU Leuven Zemni, Sami, Universiteit Gent Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century Benjamin Nickl Leuven University Press Published with the support of the Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand University of Sydney and KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © Benjamin Nickl, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. The licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non- commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: B. Nickl. 2019. Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment: Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licences -

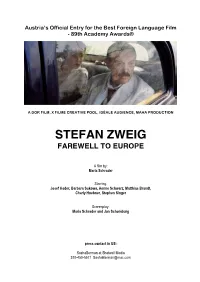

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

Wir Brauchen Einen Ganz Anderen Mut. Stefan Zweig – Abschied Von Europa 3

Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien www.theatermuseum.at JÄNNER 2014 Wir brauchen einen ganz anderen Mut. Stefan Zweig – Abschied von Europa 3. April 2014 bis 12. Jänner 2015 ZUR AUSSTELLUNG Als der österreichische Schriftsteller Stefan Zweig (1881–1942) 1934 nach England und in der Folge nach Brasilien emigrierte, verließ ein überaus erfolgreicher Autor Europa. Dennoch sind es zwei Werke, die Zweig erst im Exil verfasst hat, die heute sein Bild bestimmen. Im Blick auf Die Welt von Gestern und die Schachnovelle entdeckt das Theatermuseum Zweigs Leben und Werk auf neue Weise. Es ist die Perspektive der Vertreibung, die die Ausstellung charakterisiert. Angelpunkt der Gestaltung ist das „Metropol“, das als mondänes Hotel das Fin de siècle ebenso repräsentiert, wie es als Gestapo-Hauptquartier zum Schreckensort schlechthin wurde. PressefOTOS Die Bilder sind für die Berichterstattung über die Ausstellung frei und stehen zum Download bereit unter www.theatermuseum.at/presse/ © Stefan Zweig Centre Salzburg Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien www.theatermuseum.at JÄNNER 2014 Trägt die Sprache schon Gesang in sich... Richard Strauss und die Oper 12. Juni 2014 bis 9. Februar 2015 ZUR AUSSTELLUNG Richard Strauss zählt zu den wichtigsten Komponisten der beginnenden Moderne und wurde als Opernkomponist in aller Welt geschätzt. Strauss unterhielt zahlreiche Verbindungen nach Wien, wo er zwischen 1919 und 1924 als Direktor der Wiener Staatsoper große Triumphe, aber auch zahlreiche Niederlagen erlebte. Anlässlich seines 150. Geburtstages präsentiert das Theatermuseum seine umfangreichen Strauss-Bestände, unter ihnen die Korrespondenz mit Hugo von Hofmannsthal sowie den großen Schatz an Bühnenbild- und Kostümentwürfen von Alfred Roller. PressefOTOS Die Bilder sind für die Berichterstattung über die Ausstellung frei und stehen zum Download bereit unter www.theatermuseum.at/presse/ © Theatermuseum. -

German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2004/1 The Expulsion of the ‘German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War Edited by STEFFEN PRAUSER and ARFON REES BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author(s). © 2004 Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees and individual authors Published in Italy December 2004 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50016 San Domenico (FI) Italy www.iue.it Contents Introduction: Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees 1 Chapter 1: Piotr Pykel: The Expulsion of the Germans from Czechoslovakia 11 Chapter 2: Tomasz Kamusella: The Expulsion of the Population Categorized as ‘Germans' from the Post-1945 Poland 21 Chapter 3: Balázs Apor: The Expulsion of the German Speaking Population from Hungary 33 Chapter 4: Stanislav Sretenovic and Steffen Prauser: The “Expulsion” of the German Speaking Minority from Yugoslavia 47 Chapter 5: Markus Wien: The Germans in Romania – the Ambiguous Fate of a Minority 59 Chapter 6: Tillmann Tegeler: The Expulsion of the German Speakers from the Baltic Countries 71 Chapter 7: Luigi Cajani: School History Textbooks and Forced Population Displacements in Europe after the Second World War 81 Bibliography 91 EUI WP HEC 2004/1 Notes on the Contributors BALÁZS APOR, STEFFEN PRAUSER, PIOTR PYKEL, STANISLAV SRETENOVIC and MARKUS WIEN are researchers in the Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute, Florence. TILLMANN TEGELER is a postgraduate at Osteuropa-Institut Munich, Germany. Dr TOMASZ KAMUSELLA, is a lecturer in modern European history at Opole University, Opole, Poland. -

A Hero's Work of Peace: Richard Strauss's FRIEDENSTAG

A HERO’S WORK OF PEACE: RICHARD STRAUSS’S FRIEDENSTAG BY RYAN MICHAEL PRENDERGAST THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Music with a concentration in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Associate Professor Katherine R. Syer ABSTRACT Richard Strauss’s one-act opera Friedenstag (Day of Peace) has received staunch criticism regarding its overt militaristic content and compositional merits. The opera is one of several works that Strauss composed between 1933 and 1945, when the National Socialists were in power in Germany. Owing to Strauss’s formal involvement with the Third Reich, his artistic and political activities during this period have invited much scrutiny. The context of the opera’s premiere in 1938, just as Germany’s aggressive stance in Europe intensified, has encouraged a range of assessments regarding its preoccupation with war and peace. The opera’s defenders read its dramatic and musical components via lenses of pacifism and resistance to Nazi ideology. Others simply dismiss the opera as platitudinous. Eschewing a strict political stance as an interpretive guide, this thesis instead explores the means by which Strauss pursued more ambiguous and multidimensional levels of meaning in the opera. Specifically, I highlight the ways he infused the dramaturgical and musical landscapes of Friedenstag with burlesque elements. These malleable instances of irony open the opera up to a variety of fresh and fascinating interpretations, illustrating how Friedenstag remains a lynchpin for judiciously appraising Strauss’s artistic and political legacy. -

Inhalt. Seilt Geleitwort

Inhalt. Seilt Geleitwort. Von Clara Körben . 3 I. Aus österreichischem Geiste. Aphorismen. Von Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach 9 Der Schleier der Beatrice (Schlußverse). Von Arthur Schnitzler .... 10 Die verwandelte Welt. Von Hans Müller 11 Das Landgut der Fiametta. Von Raoul Auernheimer 13 Lemberg. Von Thaddäus Rittner 22 Die Flöte. Von Franz Karl Ginzkey 23 Die Helfenden. Von Lola Lorme 24 Bischof Dr. Rudolf Hittmair und Enrita von Handel-Mazzetti. Mitgeteilt von Enrika von Handel-Mazzetti (aus der Hittmair-Biographie von Pesendorfer) . 25 Ostermorgen im Felde. Von Mathilde Gräfin Stubenberg 30 Deutsches Wiegenlied. Von Alfons Petzold 30 Dem Hiasl fei Feldpost (steirisch). Von Hermann Kienzl 31 Der Sommer. Von Peter Attenberg 32 Der Frosch. Von Peter Altenberg 32 Deutsche Lehre. Von Hans Fraungruber 33 Die Leute vom blauen Guguckshaus. Von Emil Ertl (aus der Roman- Trilogie „Ein Volk an der Arbeit") 33 Adria-Idyllen. Von Irma von Höfer 45 England und die Kulturphilosophie Bacon-Shakespeares in ihren Beziehungen zum gegenwärtigen Weltkrieg. Von Hofrat Alfred von Weber-Ebenhof 50 St. Michael. Von Gabriele Fürstin Wrede 64 Echt österreichisch. Von Marianne Schrutka von Rechtenstamm ... 65 Zwei Tannen. Don Else Rubricius 66 II. An Österreichs Schwert. Zum 18. August 1915. Von Peter Rosegger 69 Das große Händefalten. Von Anton Wildgans 69 Mein Österreich. Von Richard Schaukal 71 Die Kriegssage vom Untersberg. Von GiselavonBerger 72 Die Glocken kommen. Von Angelika von Hörmann 76 Schwertbrüder. Von Karl Rogner 77 Österreichisches Reiterlied. Von Hugo Iuckermannf . 78 Przemysl. Von Maria Eugenia teile Grazie 79 Weihnachten in Przemysl. Von Herma von Skoda 80 Aus» Osterreich, aus. Von HermavonSkoda 81 5 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch N/" http://d-nb.info/362276870 31 "HEI1 Seite Mein Bub. -

The Idea of America in Austrian Political Thought 1870-1960

The Idea of America in Austrian Political Thought 1870-1960 David Wile Advisor: Dr. Alan Levine, School of Public Affairs University Honors Spring 2012 Wile 1 Abstract Between 1870 and 1960, the United States of America and Austria experienced two opposite political paths. The United States emerged from the wreckage of the Civil War as a more centralized republic and at the turn of the century became an imperial power, a status that the First and Second World Wars only solidified. Meanwhile, Austria ended the nineteenth century as one of Europe’s largest empires, yet after World War I, all that remained of the intellectual and cultural center of the Habsburg Empire was a tiny remnant cut off from its breadbasket in Hungary, its industrial center in Bohemia, and its seaports in the Balkans. Against the backdrop of a dying empire observing a nascent one, this project examines the discourse through which prominent members of the Austrian, and especially Viennese, intellectual elite imagined the United States of America, and attempts to determine which patterns emerged in that discourse. The Austrian thinkers and writers who are the major focus of this work are: the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, the Zionist Theodor Herzl, the feuilletonist and satirist Karl Kraus, two of the most prominent members of the Austrian School of economics, Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek, and an economist of the Historical School, Joseph Schumpeter. To a lesser extent, the work refers to writers Stefan Zweig, Albert Kubin, and Arthur Schnitzler, philosophers Otto Weininger and Franz Brentano, and two more Austrian School economists, Carl Menger and Friedrich von Wieser. -

Cultural Amnesia

Marcel Reich-Ranicki arcel Reich-Ranicki (b. 1920), by far the most famous critic in Germany between World War II Mand the millennium, continues, into the twenty-first century, to exercise, over the German literary scene, a dominance which some writers prefer to regard as a reign of terror. Actually there can be no real argument about the fairness of his judgements – a fact which, of course, makes his disapproval feel even worse for those found wanting. He writes so well that his opinions are quoted verbatim. Victims of a put-down are thus faced with the prospect of becoming a national joke. Most of those writers whose later books were savaged by him had their early books praised by him: those are the writers who become most resentful of all against him. Well equipped to look after himself, he is hard to lay a glove on. Watching magisterial figures such as Günter Grass vainly trying to get their own back on Reich-Ranicki is one of the entertainments of modern Germany. Even those wounded by him would have to admit, under scopolamine, that he can be very funny when on the attack. Hence their intense enjoyment of the moment when history caught him out. Deported from Berlin to the Warsaw ghetto in 1938, Reich-Ranicki survived the Holocaust but stayed on in Communist Poland after the war, and first pursued literary criticism under East German auspices. When he finally defected to the West he forgot to tell anyone that he had been a registered informer under the regime he left behind. -

Integration of East German Resettlers Into the Cultures and Societies of the GDR

Integration of East German Resettlers into the Cultures and Societies of the GDR Doctoral Thesis of Aaron M.P. Jacobson Student Number 59047878 University College London Degree: Ph.D. in History 1 DECLARATION I, Aaron M.P. Jacobson, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT A controversy exists in the historiography of ethnic German post-WWII refugees and expellees who lived in the German Democratic Republic. This question is namely: to what extent were these refugees and expellees from various countries with differing cultural, religious, social and economic backgrounds integrated into GDR society? Were they absorbed by the native cultures of the GDR? Was an amalgamation of both native and expellee cultures created? Or did the expellees keep themselves isolated and separate from GDR society? The historiography regarding this controversy most commonly uses Soviet and SED governmental records from 1945-53. The limitation of this approach by historians is that it has told the refugee and expellee narrative from government officials’ perspectives rather than those of the Resettlers themselves. In 1953 the SED regime stopped public record keeping concerning the Resettlers declaring their integration into GDR society as complete. After eight years in the GDR did the Resettlers feel that they were an integrated part of society? In an attempt to ascertain how Resettlers perceived their own pasts in the GDR and the level of integration that occurred, 230 refugees and expellees were interviewed throughout the former GDR between 2008-09. -

Hermann Hesse As Ambivalent Modernist Theodore Jackson Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) January 2010 Hermann Hesse as Ambivalent Modernist Theodore Jackson Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Jackson, Theodore, "Hermann Hesse as Ambivalent Modernist" (2010). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 167. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/167 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures Dissertation Examination Committee: Lutz Koepnick, Chair Matt Erlin Paul Michael Lützeler Stamos Metzidakis Richard Ruland Stephan Schindler HERMANN HESSE AS AMBIVALENT MODERNIST by Theodore Saul Jackson A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 Saint Louis, Missouri copyright by Theodore Saul Jackson 2010 Acknowledgements I am indebted to the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures as well as the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences for providing funding for this project in the form of a dissertation fellowship for the 2009–2010 school year, and for continuous funding throughout my graduate career. Special thanks are in order for my advisor, Lutz Koepnick, and the rest of my research advisory committee for reading drafts and providing valuable feedback during the writing process. I would also like to thank the German-American Fulbright Commission for providing me with a year in which I could complete valuable research on Hesse’s life and on the organizations of the German youth movement. -

Original Intelligence and Neurological Disease in Stefan Zweig's Chess Story

4EN) 18-2014 Ajedrez_Neurosciences&History 24/04/15 14:28 Página 30 Original Neurosciences and History 2015; 3(1):30-41 Intelligence and neurological disease in Stefan Zweig's Chess Story L.C. Álvaro González 1, A. Álvaro Martín del Burgo 2 1Department of Neurology, Hospital Universitario Basurto, Bilbao; Department of Neuroscience, UPV/ EHU, Spain. 2Student. Part of this study was presented as an oral communication at the 66th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology, Valencia, November 2014. ABSTRACT Introduction and objectives. Stefan Zweig (Vienna 1881-Petrópolis 1942) was a highly successful essayist and novelist in his own lifetime. As an Austrian-born Jew and a cosmopolitan freethinker, he was persecuted and his works were prohibited in Nazi Germany and its occupied territories before he was forced into exile. Chess Story , a cornerstone of his later works, contains neurological references that we will examine here. Methods. We present a reading of this novel in which we 1) identify excerpts with neurological relevance; 2) analyse its biographical and historical context (1941); and 3) use the above to complete a critical rereading and interpre - tation. Results . One of the main characters displays 1) an extraordinary ability for chess and savant-like features; the protagonist, in stark contrast is an imaginative intellectual who became a self-taught chess player by chance. After being imprisoned and held in solitary confinement by the Nazis, he survives thanks to chess, his practical intelli - gence, and his resilience. During his time in solitary confinement, he experiences 2) an induced deafferentation syndrome with emotional and agitated symptoms compatible with delirium or confusional syndrome.