Jacob's Blessing, Cooperative Grace, and Practicing Law with a Limp John M.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Baseball's Status in American Sport and Television

University of Central Florida STARS On Sport and Society Public History 10-18-1995 Baseball's Status in American Sport and Television Richard C. Crepeau University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Cultural History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Public History at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in On Sport and Society by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crepeau, Richard C., "Baseball's Status in American Sport and Television" (1995). On Sport and Society. 434. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety/434 SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR H-ARETE October 18, 1995 Sometimes the worst laid plans of mice and men cannot do their damage. In the case of the major league baseball owners again they tried. But try as they might, they haven't been able to destroy the post-season. It all stated in the divisional playoffs when all four games were played at exactly the same time, so that the audience could be regionalized. In the League Championship Series or LCS(which has the ominous sound of a religious cult) the Baseball Network again repeated their minimalist pattern starting both games simultaneously. There was one improvement. When one game ended they switched to the other, and some late inning tension was enjoyed nationally. -

Oakland Raiders 1

NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” BW Unlimited is proud to provide this incredible list of hand signed Sports Memorabilia from around the U.S. All of these items come complete with a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) from a 3rd Party Authenticator. From Signed Full Size Helmets, Jersey’s, Balls and Photo’s …you can find everything you could possibly ever want. Please keep in mind that our vast inventory constantly changes and each item is subject to availability. When speaking to your Charity Fundraising Representative, let them know which items you would like in your next Charity Fundraising Event: Hand Signed Sports Memorabilia California Angels 1. Nolan Ryan Signed California Angels Jersey 7 No Hitters PSA/DNA (BWU001IS) $439 2. Nolan Ryan Signed California Angels 16x20 Photo SI & Ryan Holo (BWU001IS) $210 3. Nolan Ryan California Angels & Amos Otis Kansas City Royals Autographed 8x10 Photo -Pitching- (BWU001EPA) $172 4. Autographed Don Baylor Baseball Inscribed "MVP 1979" (BWU001EPA) $124 5. Rod Carew California Angels Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $304 6. Wally Joyner Autographed MLB Baseball (BWU001EPA) $148 7. Wally Joyner Autographed Big Stick Bat With His Name Printed On The Bat (BWU001EPA) $176 8. Wally Joyner California Angels Autographed Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $280 9. Mike Witt Autographed MLB Baseball Inscribed "PG 9/30/84" (BWU001EPA) $148 L.A. Dodgers 1. Fernando Valenzuela Signed Dodgers Jersey (BWU001IS) $300 2. Autographed Fernando Valenzuela Baseball (BWU001EPA) $232 3. Autographed Fernando Valenzuela Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $388 4. Duke Snider signed baseball (BWU001IS) $200 5. Tommy Lasorda signed jersey dodgers (BWU001IS) $325 6. -

Postseaason Sta Rec Ats & Caps & Re S, Li Ecord Ne S Ds

Postseason Recaps, Line Scores, Stats & Records World Champions 1955 World Champions For the Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1955 World Series was not just a chance to win a championship, but an opportunity to avenge five previous World Series failures at the hands of their chief rivals, the New York Yankees. Even with their ace Don Newcombe on the mound, the Dodgers seemed to be doomed from the start, as three Yankee home runs set back Newcombe and the rest of the team in their opening 6-5 loss. Game 2 had the same result, as New York's southpaw Tommy Byrne held Brooklyn to five hits in a 4-2 victory. With the Series heading back to Brooklyn, Johnny Podres was given the start for Game 3. The Dodger lefty stymied the Yankees' offense over the first seven innings by allowing one run on four hits en route to an 8-3 victory. Podres gave the Dodger faithful a hint as to what lay ahead in the series with his complete-game, six-strikeout performance. Game 4 at Ebbets Field turned out to be an all-out slugfest. After falling behind early, 3-1, the Dodgers used the long ball to knot up the series. Future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella and Duke Snider each homered and Gil Hodges collected three of the club’s 14 hits, including a home run in the 8-5 triumph. Snider's third and fourth home runs of the Series provided the support needed for rookie Roger Craig and the Dodgers took Game 5 by a score of 5-3. -

North America's Charity Fundraising

NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” Hand Signed Guitars (signed on the Pic Guard) Cost to Non Profit: $1,500.00 Suggested Retail Value: $3,100.00 plus 1. Aerosmith 2. AC/DC 3. Bon Jovi 4. Bruce Springsteen 5. Dave Matthews 6. Eric Clapton 7. Guns N’ Roses 8. Jimmy Buffett 9. Journey 10. Kiss 11. Motely Crue 12. Neil Young 13. Pearl Jam 14. Prince 15. Rush 16. Robert Plant & Jimmy Page 17. Tom Petty 18. The Police 19. The Rolling Stones 20. The Who 21. Van Halen 22. ZZ Top BW Unlimited, llc. www.BWUnlimited.com Page 1 NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” Hand Signed Custom Framed & Matted Record Albums Premium Design Award Style with Gold/ Platinum Award Album Cost to Non Profit: $1,300.00 Gallery Retail Price: $4,200.00 - Rolling Stones & Pink Floyd - $1,600.00 - Gallery Price - $3,700.00 Standard Design with original vinyl Cost to Non Profit: $850.00 Gallery Retail Price: $2,800.00 - Rolling Stones & Pink Floyd - $1,100.00 Gallery Price - $3,700.00 BW Unlimited, llc. www.BWUnlimited.com Page 2 NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” Lists of Available Hand Signed Albums: (Chose for framing in the above methods): 1. AC/DC - Back in Black 42. Guns N' Roses - Use your Illusion II 2. AC/DC - For those about to Rock 43. Heart - Greatest Hits 3. Aerosmith - Featuring "Dream On" 44. Heart - Little Queen 4. Aerosmith - Classics Live I 45. Jackson Browne - Running on Empty 5. Aerosmith - Draw the Lin 46. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

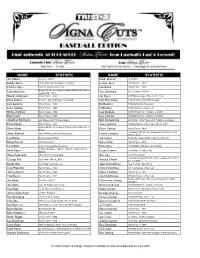

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

Lugnuts Media Guide & Record Book

Lugnuts Media Guide & Record Book Table of Contents Lugnuts Media Guide Staff Directory ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Executive Profiles ............................................................................................................................................................................................................4 The Midwest League Midwest League Map and Affiliation History .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Bowling Green Hot Rods / Dayton Dragons ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Fort Wayne TinCaps / Great Lakes Loons ...................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Lake County Captains / South Bend Cubs ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 West Michigan Whitecaps ............................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Youth Baseball Edition

95482 cover final 9/22/04 9:24 AM Page 2 ® Youth Baseball Edition 95482 cover final 9/22/04 9:24 AM Page 3 The Catalog for Giving is a new solution Each organization generally must: and a philanthropic success story. · Have IRS 501 (c) (3) status · Operate with annual budgets less than $1 million This is no typical Catalog. It offers opportunities for giving, not buying. · Provide direct service to children and young people This special edition of The Catalog features profiles of youth baseball · Have no partisan affiliation or ideology organizations that are changing young lives and doing it on budgets max- The Catalog describes the background activities and goals that define imized to benefit the young people they serve. These are grassroots sports each organization, giving donors compelling insights without hype. programs that need donors who can help sustain their operations. Catalogs bound with a payment form and a business reply envelope are distributed to individuals, foundations, and corporations. Donors can con- The Catalog for Giving is a philanthropic success that provides donors with nect with a cause as quickly and easily as they might choose consumer a reliable guide to well-researched, effective groups and an easy path to goods - but with confidence, enthusiasm and understanding, and with infi- supporting them. It’s a new concept, and it works. In ten years, the model nitely more reward. Unlike some other catalog fundraising efforts, donors program - The Catalog for Giving of New York City - raised $7 million for are charged no fees for making a gift. -

1986 Fleer Baseball Card Checklist

1986 Fleer Baseball Card Checklist 1 Steve Balboni 2 Joe Beckwith 3 Buddy Biancalana 4 Bud Black 5 George Brett 6 Onix Concepcion 7 Steve Farr 8 Mark Gubicza 9 Dane Iorg 10 Danny Jackson 11 Lynn Jones 12 Mike Jones 13 Charlie Leibrandt 14 Hal McRae 15 Omar Moreno 16 Darryl Motley 17 Jorge Orta 18 Dan Quisenberry 19 Bret Saberhagen 20 Pat Sheridan 21 Lonnie Smith 22 Jim Sundberg 23 John Wathan 24 Frank White 25 Willie Wilson 26 Joaquin Andujar 27 Steve Braun 28 Bill Campbell 29 Cesar Cedeno 30 Jack Clark 31 Vince Coleman 32 Danny Cox 33 Ken Dayley 34 Ivan DeJesus 35 Bob Forsch 36 Brian Harper 37 Tom Herr 38 Ricky Horton 39 Kurt Kepshire 40 Jeff Lahti 41 Tito Landrum 42 Willie McGee 43 Tom Nieto 44 Terry Pendleton Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 45 Darrell Porter 46 Ozzie Smith 47 John Tudor 48 Andy Van Slyke 49 Todd Worrell 50 Jim Acker 51 Doyle Alexander 52 Jesse Barfield 53 George Bell 54 Jeff Burroughs 55 Bill Caudill 56 Jim Clancy 57 Tony Fernandez 58 Tom Filer 59 Damaso Garcia 60 Tom Henke 61 Garth Iorg 62 Cliff Johnson 63 Jimmy Key 64 Dennis Lamp 65 Gary Lavelle 66 Buck Martinez 67 Lloyd Moseby 68 Rance Mulliniks 69 Al Oliver 70 Dave Stieb 71 Louis Thornton 72 Willie Upshaw 73 Ernie Whitt 74 Rick Aguilera 75 Wally Backman 76 Gary Carter 77 Ron Darling 78 Len Dykstra 79 Sid Fernandez 80 George Foster 81 Dwight Gooden 82 Tom Gorman 83 Danny Heep 84 Keith Hernandez 85 Howard Johnson 86 Ray Knight 87 Terry Leach 88 Ed Lynch 89 Roger McDowell 90 Jesse Orosco 91 Tom Paciorek Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 -

Which Sports Star Did That?™

DUPLICATED JESSE OWENS’ SET THE WORLD RECORD WON ONE GOLD, ONE IN THE 100 METRES AND WON WON N.H.L. MVP AWARD FEAT BY WINNING FOUR GOLD IN THE 100 METRES AND WON FIRST GYMNAST EVER CARL LEWIS MARY LOU RETTON SILVER AND TWO BRONZE LARISSA LATYNINA WON NINE OLYMPIC GOLD BEN JOHNSON THE EVENT AT THE 1988 NADIA COMANECI GORDIE HOWE 6 TIMES AND HOLDS THE MEDALS AT THE 1984 OLYMPICS TO SCORE A PERFECT (U.S.A.) (U.S.A.) MEDALS IN GYMNASTICS AT (FORMER U.S.S.R.) MEDALS IN GYMNASTICS (CANADA) OLYMPICS BUT BOTH WERE (ROMANIA) (CANADA) RECORD FOR THE MOST ININ 100M,100M, 200M,200M, 44 XX 100M100M 10 AT AN OLYMPICS THE 1984 OLYMPICS REVOKED WHEN HE FAILED GAMES PLAYED (1767) RELAY AND LONG JUMP A DRUG TEST WAS THE GREATEST COMPLETED THE FIRST WON THE U.S. MASTERS FIRST SWIMMER EVER TO THE ONLY HEAVYWIEGHT WAS THE FORMULA 1 HOLDS THE RECORD FOR THE EVER DOWNHILL SKIER; EVER BACKWARD SOMERSAULT FRANZ KLAMMER TIGER WOODS ININ HISHIS FIRSTFIRST YEARYEAR ASAS DAWN FRASER WIN A GOLD MEDAL IN THE OLGA KORBUT ROCKY MARCIANO BOXER TO RETIRE AS JUAN FANGIO RACING WORLD CHAMPION AYRTON SENNA MOST FORMULA 1 GRAND PRIX HE WON THE WORLD CUP ON THE BALANCE BEAM; SHE (AUSTRIA) (U.S.A.) A PROFESSIONAL GOLFER (AUSTRALIA) SAME EVENT (100M FREESTYLE) (FORMER U.S.S.R.) (U.S.A.) UNDEFEATED CHAMPION (ARGENTINA) FIVE TIMES - MORE THAN ANY (BRAZIL) VICTORIES IN ONE YEAR, WITH TITLE FOUR TIMES WON THREE GOLD MEDALS AT ININ 19971997 AT 3 CONSECUTIVE OLYMPICS AT 49-0 OTHER DRIVER 8 IN 1988 ININ THETHE 1970’S1970’S THE 1972 OLYMPICS THIS SKIIER WAS THE WAS STABBED IN TENNIS STAR WON WON THE GOLD MEDAL FIRST PROFESSIONAL HIT HIS HEAD ON THE INGEMAR WORLD CUP OVERALL THE BACK WHILE SEATED THE FIRST OF HER U.S. -

The Story of Baseball Medicine...Is a Story of How We Arrived at Today and Where We Are Going Tomorrow

A Review Paper The Process of Progress in Medicine, in Sports Medicine, and in Baseball Medicine Frank W. Jobe, MD, and Marilyn M. Pink, PhD, PT ome years ago, a mentor once said “I’m not inter- Ancient Greece ested in what you know as much as I’m interested The time of the Ancient Greeks was around 500 BC. in how you think.” That was a very curious state- Herodicus is one of the first progressive medical practitio- ment for an orthopedic surgeon. Doesn’t a surgeon ners of whom we know. Herodicus was a “gymnast”—a Shave to know the facts of the human body? Wasn’t that physician who interested himself in all phases of an ath- “what” I knew? lete’s training. Literally, gymnase in Greek means naked. Now, when at the opposite end of the career spectrum, And, it was Herodicus himself who recommended that the the wisdom behind those words is apparent. “How we athletes exercise and compete in the nude in order to keep think” determines the progress we’ll make. “What we as cool as possible and to perspire freely in the humidity. think” is that which we memorized to get through medical school and is good only for today. With that in mind, the story of baseball medicine is not “...the story of baseball just a story of baseball statistics—rather, it is a story of medicine...is a story of how how we arrived at today and where we are going tomor- row. If we are wise, we can learn from the story: we won’t we arrived at today and need to repeat history, but rather we can look at the com- where we are going tomorrow.” monalities in the progressive steps and invent our future.