Management Plan for Black Bears in Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CBA/ABC Bulletin 35(1)

THE CANADIAN BOTANICAL ASSOCIATION BULLETIN DE LASSOCIATION BOTANIQUE DU CANADA February / février 2002 35(1) Montréal Patron / Président d'honneur Her Excellency the Right Honourable / Son excellence la très honorable Adrienne Clarkson, C.C., C.M.M., C.D. Governor General of Canada / Gouverneure générale du Canada On the inside / À l'intérieur I Presidents Message I This issue of the bulletin is the last one to be produced by Denis Lauzer. I am sure you will all agree that Denis has done a wonderful job bringing us all up to date on the current happenings in our Association. Thank you, Denis, for all the 2 Page time you have invested producing such an excellent publication. Editors / La rédaction CBA Section and Committee Chairs The next issue of the Bulletin will be produced in Edmundston, NB, under the direction of our new Editor, Martin Dubé. We look forward to the continued production of an informative and interesting Bulletin under his editorship. Page 3 Plans are being finalized for our next Annual Meeting (August 4-7), to be President's Message (continued) held at the Pyle Conference Center on the campus of the University of Wisconsin Macoun Travel Boursary in Madison, Wisconsin. The deadline for submission of abstracts is now estab- 2002 CBA Annual Meeting / lished (April 1, 2002) and we now have a list of planned Symposia. The subject Congrès annuel de l'ABC 2002 of the Plenary Symposium is Evolution: Highlighting Plants, organized by Patricia Gensel. Sectional Symposia of the Botanical Socie ty of America (with input from Page 4 CBA Sections) include the following: Poorly Known Economic Plants of Canada - 32. -

The Role of Forage Availability on Diet Choice and Body Condition in American Beavers (Castor Canadensis)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 2013 The oler of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis) William J. Severud Northern Michigan University Steve K. Windels National Park Service Jerrold L. Belant Mississippi State University John G. Bruggink Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark Severud, William J.; Windels, Steve K.; Belant, Jerrold L.; and Bruggink, John G., "The or le of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis)" (2013). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 124. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/124 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Mammalian Biology 78 (2013) 87–93 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Mammalian Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mambio Original Investigation The role of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis) William J. Severud a,∗, Steve K. Windels b, Jerrold L. Belant c, John G. Bruggink a a Northern Michigan University, Department of Biology, 1401 Presque Isle Avenue, Marquette, MI 49855, USA b National Park Service, Voyageurs National Park, 360 Highway 11 East, International Falls, MN 56649, USA c Carnivore Ecology Laboratory, Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Mississippi State University, Box 9690, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA article info abstract Article history: Forage availability can affect body condition and reproduction in wildlife. -

Nodulation and Growth of Shepherdia × Utahensis ‘Torrey’

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 12-2020 Nodulation and Growth of Shepherdia × utahensis ‘Torrey’ Ji-Jhong Chen Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Chen, Ji-Jhong, "Nodulation and Growth of Shepherdia × utahensis ‘Torrey’" (2020). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7946. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7946 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NODULATION AND GROWTH OF SHEPHERDIA ×UTAHENSIS ‘TORREY’ By Ji-Jhong Chen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Plant Science Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Youping Sun, Ph.D. Larry Rupp, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Jeanette Norton, Ph.D. Heidi Kratsch, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member _______________________________________ Richard Cutler, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2020 ii Copyright © Ji-Jhong Chen 2020 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Nodulation and Growth of Shepherdia × utahensis ‘Torrey’ by Ji-Jhong Chen, Master of Science Utah State University, 2020 Major Professor: Dr. Youping Sun Department: Plants, Soils, and Climate Shepherdia × utahensis ‘Torrey’ (hybrid buffaloberry) (Elaegnaceae) is presumable an actinorhizal plant that can form nodules with actinobacteria, Frankia (a genus of nitrogen-fixing bacteria), to fix atmospheric nitrogen. However, high environmental nitrogen content inhibits nodule development and growth. -

The Genetic Structure of American Black Bear Populations in the Southern Rocky Mountains

THE GENETIC STRUCTURE OF AMERICAN BLACK BEAR POPULATIONS IN THE SOUTHERN ROCKY MOUNTAINS Rachel C. Larson, Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, University of Wisconsin – Madison, 1630 Linden Dr., Madison, WI 53706 Rebecca Kirby, Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, University of Wisconsin – Madison, 1630 Linden Dr., Madison, WI 53706 Nick Kryshak, Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, University of Wisconsin – Madison, 1630 Linden Dr., Madison, WI 53706 Mathew Alldredge, Colorado Parks & Wildlife, Fort Collins, Colorado, 80525 David B. McDonald, Department of Zoology & Physiology, University of Wyoming, 1000 E. University Ave. Laramie, WY 80721 Jonathan N. Pauli, Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, University of Wisconsin – Madison, 1630 Linden Dr., Madison, WI 53706 ABSTRACT: Large and wide-ranging carnivores typically display genetic connectivity across their distributional range. American black bears (Ursus americanus) are vagile carnivores and habitat generalists. However, they are strongly associated with forested habitats; consequently, habitat patchiness and fragmentation have the potential to drive connectivity and the resultant structure between black bear subpopulations. Our analysis of genetic structure of black bears in the southern Rocky Mountains of Wyoming and Colorado (n = 296) revealed two discrete populations: bears in northern Wyoming were distinct (FST = 0.217) from bears in southern Wyoming and Colorado, despite higher densities of anthropogenic development within Colorado. The differentiation we observed indicates that bears in Wyoming originated from two different clades with structure driven by the pattern of contiguous forest, rather than the simple distance between populations. We posit that forested habitat and competitive interactions with brown bears reinforced patterns of genetic structure resulting from historic colonization. -

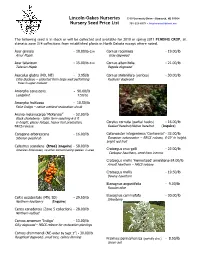

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Silver Buffaloberry

Silver Buffaloberry slide 4a 400% slide 4b 360% slide 4c slide 4d 360% 360% III-5 Silver Buffaloberry Environmental Requirements (Shepherdia argentea) Soils Soil Texture - Grows well in most soils. Soil pH - 5.5 to 8.0. Adapted to moderately alkaline and General Description saline soils. A tall, thorny, thicket-forming native shrub. Well adapted Windbreak Suitability Group - 1, 1K, 3, 4, 4C, 5, 6D, 6G, 8, to dry, moderately alkaline and saline soils. Tolerates 9C, 9L. infertile soils, in part because of its ability to fix and assimilate atmospheric nitrogen. Berries used for jellies. Cold Hardiness USDA Zone - 2. Leaves and Buds Bud Arrangement - Opposite. Water Drought tolerant. Not adapted to wet, poorly-drained Bud Color - Silvery. sites. Bud Size - Small, solitary or multiple, stalked, oblong. Leaf Type and Shape - Simple, oblong-elliptical. Light Leaf Margins - Entire. Full sun. Leaf Surface - Finely-scaled, pubescent. Uses Leaf Length - 1 to 2 inches. Leaf Width - 1/4 to 5/8 inch. Conservation/Windbreaks Leaf Color - Silvery-gray on both surfaces. Medium to tall shrub for farmstead and field windbreaks, riparian plantings, and highway beautification. Flowers and Fruits Flower Type - Dioecious. Wildlife Highly important for mule deer browse. Ideal cover and Flower Color - Yellowish. nesting site for many birds. Preferred food source of many Fruit Type - Drupe-like, insipid, ovoid. songbirds and sharptail grouse. Good late winter food Fruit Color - Predominately red, however, some female source for birds. plants can produce yellow fruits. Agroforestry Products Form Food - Fruit processed as jams and jellies. Growth Habit - Loosely branched shrub of rounded outline. Urban/Recreational Ornamental foliage and fruit, but limited in use because of Texture - Medium-fine, summer; fine, winter. -

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids . oaks, birches, evening primroses . a major group of the woody plants (trees/shrubs) present at your sites The Wind Pollinated Trees • Alternate leaved tree families • Wind pollinated with ament/catkin inflorescences • Nut fruits = 1 seeded, unilocular, indehiscent (example - acorn) *Juglandaceae - walnut family Well known family containing walnuts, hickories, and pecans Only 7 genera and ca. 50 species worldwide, with only 2 genera and 4 species in Wisconsin Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Leaves pinnately compound, alternate (walnuts have smallest leaflets at tip) Leaves often aromatic from resinous peltate glands; allelopathic to other plants Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family The chambered pith in center of young stems in Juglans (walnuts) separates it from un- chambered pith in Carya (hickories) Juglans regia English walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Trees are monoecious Wind pollinated Female flower Male inflorescence Juglans nigra Black walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Male flowers apetalous and arranged in pendulous (drooping) catkins or aments on last year’s woody growth Calyx small; each flower with a bract CA 3-6 CO 0 A 3-∞ G 0 Juglans cinera Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Female flowers apetalous and terminal Calyx cup-shaped and persistant; 2 stigma feathery; bracted CA (4) CO 0 A 0 G (2-3) Juglans cinera Juglans nigra Butternut, white -

Troth Yeddha

PROPOSAL TO NAME A GEOGRAPHIC FEATURE IN ALASKA ALASKA HISTORICAL COMMISSION ACTION REQUESTED Department of Natural Resources Office of History and Archaeology 550 West 7th Ave., Suite 1310 _X new name Anchorage, AK 99501‐3565 __application change (907) 269‐8721 [email protected] __name change __other DESCRIPTION: • Proposed name: Troth Yeddha’ • Type of feature: ridge • Evidence the feature is unnamed: Unofficial designations include “West Ridge”, “Lower Campus” and “College Hill,” but none of these has official status in GNIS. Moreover, these unofficial names refer to particular sub-regions of the ridge as opposed to the entire feature. LOCATION: ridge at the site of University of Alaska Distance and direction from nearest community or prominent topographic feature: one-quarter to three-quarters of a mile west o f College, Alaska Borough: Fairbanks North Star Borough USGS map: Fairbanks D‐2 Latitude: 64° 51.663' N Longitude: 147° 51.170 W Elev: 614' Section: 1 to 6, Township: T1S Range: R2W to R1W TYPE OF PROPOSAL: LOCAL USAGE Is the proposed name in local use? Yes (see description) State the number of years known by recommended name: Traditional Athabascan name of unknown antiquity, first recorded in 1967 by linguist Michael Krauss. State variant spelling and/or usage if known: Troth Yetth, Tro Yeddha’, Troyeddha’, Troth Yedda, Tsoł Yedla’, Tsoł Teye’ Is there local opposition or conflict regarding the proposed name? The proposed spelling Troth Yeddha’ is widespread and is preferred by Lower Tanana Athabascan speakers and the Alaska Native Language Center. The name is being submitted without a generic term such as “Ridge”. -

Wildlife Viewing

Wildlife Viewing Common Yukon roadside flowers © Government of Yukon 2019 ISBN 987-1-55362-830-9 A guide to common Yukon roadside flowers All photos are Yukon government unless otherwise noted. Bog Laurel Cover artwork of Arctic Lupine by Lee Mennell. Yukon is home to more than 1,250 species of flowering For more information contact: plants. Many of these plants Government of Yukon are perennial (continuously Wildlife Viewing Program living for more than two Box 2703 (V-5R) years). This guide highlights Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 the flowers you are most likely to see while travelling Phone: 867-667-8291 Toll free: 1-800-661-0408 x 8291 by road through the territory. Email: [email protected] It describes 58 species of Yukon.ca flowering plant, grouped by Table of contents Find us on Facebook at “Yukon Wildlife Viewing” flower colour followed by a section on Yukon trees. Introduction ..........................2 To identify a flower, flip to the Pink flowers ..........................6 appropriate colour section White flowers .................... 10 and match your flower with Yellow flowers ................... 19 the pictures. Although it is Purple/blue flowers.......... 24 Additional resources often thought that Canada’s Green flowers .................... 31 While this guide is an excellent place to start when identi- north is a barren landscape, fying a Yukon wildflower, we do not recommend relying you’ll soon see that it is Trees..................................... 32 solely on it, particularly with reference to using plants actually home to an amazing as food or medicines. The following are some additional diversity of unique flora. resources available in Yukon libraries and bookstores. -

City of Boulder Urban Wildlife Management Plan Black Bear and Mountain Lion Component Prepared for City Council Consideration of Acceptance 10/18/2011

Attachment A City of Boulder Urban Wildlife Management Plan Black Bear and Mountain Lion Component Prepared for City Council consideration of acceptance 10/18/2011 Executive Summary Chapter 1: Introduction Purpose, Problem Statement, and Objectives Issues Relationship to other City Policies and Plans The Urban Wildlife Management Plan Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan Open Space and Mountain Parks Forest Ecosystem Management Plan Zero Waste Master Plan Community Input and the Planning Process Agency Roles Chapter 2: Black Bear Behavior, Biology and Importance Analysis Nature of conflicts in the city Bear activity monitoring Current Approaches to Bear Management Evaluating Boulder’s approach to waste management Discussion of options for managing attractants Adaptive Management Plan Chapter 3: Mountain Lion Behavior, Biology and Importance Analysis Nature of conflicts in the city Lion activity monitoring Current practices Mountain Lion Awareness Plan Chapter 4: Implementation Education and Communication Practices Interdepartmental and Intergovernmental Coordination City Procedure or Regulation Development Consent Item 3D Page 6 Appendices Appendix A: Planning Process Diagram Appendix B: Black Bear Sighting Map (2009 & 2010) Appendix C: Comparison to Other Community Approaches to Trash Storage Appendix D: Mountain Lion Sighting Map (2009 & 2010) Appendix E: Discussion of Mountain Lion Management Strategies Consent Item 3D Page 7 Executive Summary The City of Boulder has a rich history of natural land protection, beginning with the purchase of 171 acres of mountain backdrop in 1898. Today, the city is surrounded on all sides by 45,000 acres of Open Space and Mountain Parks (OSMP) land with county, state and federally-owned natural lands nearby. All of these areas provide habitat for a number of native wildlife species, including black bear (Ursus americanus) and mountain lion (Puma concolor). -

Giant Panda Facts (Ailuropoda Melanoleuca)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Giant Panda Facts (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Giant panda. John J. Mosesso What animal is black and white Giant pandas are bears with one or two cubs weighing 3 to 5 and loved all over the world? If you striking black and white markings. ounces each is born in a sheltered guessed the giant panda, you’re The ears, eye patches, legs and den. Usually only one cub survives. right! shoulder band are black; the rest The eyes open at 1 1/2 to 2 months of the body is whitish. They have and the cub becomes mobile at The giant panda is also known as thick, woolly coats to insulate them approximately three months of the panda bear, bamboo bear, or in from the cold. Adults are four to six age. At 12 months the cub becomes Chinese as Daxiongmao, the “large feet long and may weigh up to 350 totally independent. While their bear cat.” In fact, its scientific pounds—about the same size as average life span in the wild is name means “black and white cat- the American black bear. However, about 15 years, giant pandas in footed animal.” unlike the black bear, giant pandas captivity have been known to live do not hibernate and cannot walk well into their twenties. Giant pandas are found only in on their hind legs. the mountains of central China— Scientists have debated for more in small isolated areas of the The giant panda has unique front than a century whether giant north and central portions of the paws—one of the wrist bones is pandas belong to the bear family, Sichuan Province, in the mountains enlarged and elongated and is used the raccoon family, or a separate bordering the southernmost part of like a thumb, enabling the giant family of their own. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below.