'The Holographic' for Developing a New Collection of Ekphrastic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astronomy and Astrophysics

THE DECADE OF DISCOVERY IN ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS Astronomy and Astrophysics Survey Committee Board on Physics and Astronomy Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications National Research Council NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C. 1991 NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS • 2101 Constitution Avenue, NW • Washington, DC 20418 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special compe_nces and with regard for appropriate balance. This report has been reviewed by a group other than the authors according to procedures approved by a Report Review Committee consisting of members of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. This project was supported by the Department of Energy under Grant No. DE-FGO5- 89ER40421, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Science Foundation under Grant No. AST-8901685, the Naval Research Laboratory under Contract No. N00173-90-M-9744, and the Smithsonian Institution under Purchase Order No. SF0022430000. Additional support was provided by the Maurice Ewing Earth and Planetary Sciences Fund of the National Academy of Sciences created through a gift from the Palisades Geophysical Institute, Inc., and an anonymous donor. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data National Research Council (U.S.). Astronomy and Astrophysics Survey Committee. The decade of discovery in astronomy and astrophysics / Astronomy and Astrophysics Survey Committee, Board on Physics and Astronomy, Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications, National Research Council. -

Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-16-2013 12:00 AM After Dark: Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age David S. Hickey The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. D.M.R. Bentley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © David S. Hickey 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hickey, David S., "After Dark: Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1805. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1805 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. After Dark: Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age Monograph by David Hickey Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Hickey 2013 i Abstract A threat to nocturnal ecosystems and human health alike, light pollution is an unnecessary problem that comes at an enormous cost. The International Dark-Sky Association has recently estimated that the energy expended on light scatter alone is responsible for no less than twelve million tons of carbon dioxide and costs municipal governments at least $1 billion annually (“Economic Issues” 2). -

Stellar Luminosity Functions of Rich Star Clusters in the Large Magellanic Cloud

A&A 369, 74–86 (2001) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20010004 & c ESO 2001 Astrophysics Stellar luminosity functions of rich star clusters in the Large Magellanic Cloud B. Santiago1, S. Beaulieu2, R. Johnson2, and G. F. Gilmore2 1 Universidade Federal Rio Grande do Sul, IF, CP 15051, Porto Alegre 91501-970, RS, Brasil 2 Institute of Astronomy, Madingley Rd., Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK Received 8 September 2000 / Accepted 12 December 2000 Abstract. We show the results of deep V and I HST photometry of 6 rich star clusters in the Large Magellanic Cloud with different ages and metallicities. The number of stars with measured magnitudes in each cluster varies from about 3000 to 10 000 stars. We build stellar density and surface brightness profiles for the clusters and extract half-light radii and other structural parameters for each. We also obtain luminosity functions, Φ(MV ), down to MV ' 6(M/M ∼> 0.9), and investigate their dependence with distance from the cluster centre well beyond their half-light radius. In all clusters we find a systematic increase in the luminosity functions slope, ∆logΦ(MV )/∆(MV ), with radial distance from the centre. Among the clusters displaying significant mass seg- regation are the 2 youngest in the sample: NGC 1805, NGC 1818. For these two clusters we obtain present day mass functions. The NGC 1818 mass function is in excellent agreement with that derived by other authors, also using HST data. The young cluster mass function slopes differ, that of NGC 1805 being systematically steeper than NGC 1818. Since these are very young stellar systems (τ ∼< 40 Myrs), these variations may reflect the initial conditions rather than evolution due to internal dynamics. -

Report for the Academic Years 1987-88 and 1988-89

Institute /or ADVANCED STUDY REPORT FOR THE ACADEMIC YEARS 1987-88 AND 1988-89 PRINCETON • NEW JERSEY nijiUfi.CAL ?""l::r"- £90"^ jr^^VTE LIBriARlf THE !f^;STiTUTE FQll AC -.MiEO STUDY PR1NCE70M, FmEW JEfiGcV 08540 AS3G TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 FOUNDERS, TRUSTEES AND OFFICERS OF THE BOARD AND OF THE CORPORATION 10 • OFFICERS OF THE ADMINISTRATION AND PROFESSOR AT LARGE 1 1 REPORT OF THE CHAIRMAN 14 REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 19 • FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT 32 REPORT OF THE SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL STUDIES ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES OF THE FACULTY MEMBERS, VISITORS AND RESEARCH STAFF 41 • REPORT OF THE SCHOOL OF MATHEMATICS ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES OF THE SCHOOL MEMBERS, VISITORS AND RESEARCH STAFF 51 REPORT OF THE SCHOOL OF NATURAL SCIENCES ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES OF THE FACULTY MEMBERS, VISITORS AND RESEARCH STAFF 58 • REPORT OF THE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES OF THE SCHOOL AND ITS FACULTY MEMBERS, VISITORS AND RESEARCH STAFF 64 • REPORT OF THE INSTITUTE LIBRARIES 66 • RECORD OF INSTITUTE EVENTS IN THE ACADEMIC YEAR 1987 - 1988 86 • RECORD OF INSTITUTE EVENTS IN THE ACADEMIC YEAR 1988 - 1989 f:i'S^o FOUNDERS, TRUSTEES AND OFFICERS OF THE BOARD AND OF THE CORPORATION Foiifidcrs CAROLINE BAMBERGER FULD LOUIS BAMBERGER The Board of Trustees [1987-1989] MARELLA AGNELLI Turin, Italy [1988- ] THORNTON F. BRADSHAW New York, New York [deceased December 6, 1988] CHARLES L. BROWN Princeton, New Jersey FLETCHER L. BYROM Carefree, Arizona GLADYS K. DELMAS New York, New York [ -1988] MICHAEL V. FORRESTAL New York, New York [deceased January 11,1 989] MARVIN L. GOLDBERGER Director Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NewJersey VARTAN GREGORIAN President New York Public Library, New York, New York WILFRIED GUTH Chairman of the Supervisory Board Deutsche Bank AG, Frankfurt, Federal Republic of Germany RALPH E. -

Rebecca Elson's Astronomical Poetry

Journal of Literature and Science Volume 12, No. 2 (2019) ISSN 1754-646X Journal of Literature and Science 12 (2019) Heuschling, “Elson’s Astronomical Poetry”: 43-61 Sophie Heuschling , “Rebecca Elson’s Astronomical Poetry”: 43-61 “Don’t Ask the Questions You’ve Been Taught by Science”: Rebecca Elson’s Astronomical Poetry Sophie Heuschling Abstract Rebecca Elson was a poet and an observational astronomer studying globular clusters and stellar evolution. Her only poetry collection, A Responsibility to Awe, was published posthumously in 2001 and offers a glimpse into the intersections and relationships between her poetry and her science. In cosmological and astronomical research, invisible and often highly mathematical and abstract objects like dark matter, gravity, and dark energy require similes and metaphors before even specialists can understand and begin to study them. This article argues that Elson used her poetry as a creative ground to explore such metaphors: in her short and condensed poems she tried out and developed various images or models for cosmological phenomena. In particular, her poems challenge conventional models of dark matter, as this article demonstrates through close readings of some of her poems. *** In an American Scientist article on the roles of analogies in science, poet, chemist, and Nobel prize laureate Roald Hoffmann writes: “These thought mappings (let’s loosely call them metaphors) also pulse deep in the heart of science. By this I mean they exist in the daily practice of doing research – in the way scientists generate hypotheses, theories and experiments” (406). In this article, Hoffmann explains the benefits of writing for scientists: writing for popular audiences or readerships encourages the use of narrative, metaphor, and analogy, which, in turn, helps the scientific researcher to better understand his or her research domain. -

Review 2013 the Royal Society of Edinburgh

cover:review2012 24/05/2013 15:04 Page 1 The Royal Society of Edinburgh The Royal Society ofEdinburgh Review 2013 Review 2013 Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling Limited, Dorchester, DT1 1HD ISSN 1476-4342 THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH REVIEW OF THE SESSION 2011-2012 PUBLISHED BY THE RSE SCOTLAND FOUNDATION ISSN 1476-4342 The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ Telephone : 0131 240 5000 Fax : 0131 240 5024 email : [email protected] Scottish Charity No SC000470 Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling Limited, Dorchester, DT1 1HD THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH REVIEW OF THE SESSION 2011-2012 PUBLISHED BY THE RSE SCOTLAND FOUNDATION ISSN 1476-4342 The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ Telephone : 0131 240 5000 Fax : 0131 240 5024 email : [email protected] Scottish Charity No SC000470 Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling Limited, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS ACTIVITIES – SESSION 2011-2012 Proceedings of the Ordinary Meetings .............................. 3 Proceedings of the Statutory General Meeting ................. 5 Prize Lectures .................................................................. 41 Lectures ........................................................................... 51 Conferences, Workshops, Symposia, Seminars and Discussion Forums ......................................................... 133 Publications ................................................................... 151 Policy Advice ................................................................. -

CONTENTS Gender Inequality Gender Inequality Nevertheless, Change Has and Cultural Change Occurred

January 2002 CONTENTS Gender Inequality Gender Inequality Nevertheless, change has and Cultural Change occurred. Gender inequity and Cultural Change may still exist, but today most By Catherine Pilachowski and Anneila Sargent Catherine Pilachowski and Anneila Sargent people recognize it for what 1 A Preface to the it is. Professionally, it is now Women Physicists and accompanying article by Alice Huang unacceptable, and the problems of an inhospitable workplace Chemists are Making ULTURAL change happens slowly. The are being addressed at all Slow Progress in Academe Committee on the Status of Women in levels. At the more personal Catherine Astronomy was formed more than 20 years Valerie Kuck C level, support networks have Pilachowski 1 ago, following two “decadal” studies that grown out of our recognition summarized the status of women in our profession. of the importance of working Things Your Professor Looking back at the statistics from these studies, and together and thanks to Should Have Told You those from the proceedings of the 1992 Women in technology of the internet. Astronomy conference at Space Telescope Science No woman need be isolated Alice Huang Institute, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that in her own institution. We are 3 progress is not just slow, but downright glacial. Add learning to empower ourselves. Women in Academe, and to the statistics all the anecdotal reports of biased or In the accompanying the Men Who Derail Them discriminatory behavior that we still hear today and article, Alice Huang, former conditions today don’t seem very different from Dean of Science and Professor Anneila Wendy Williams those that prevailed in the ‘60’s and ‘70’s. -

Carcanet Catalogue July 2018-19

New Books 2018–2019 ZOHAR ATKINS 44 MARIUS KOCIEJOWSKI 34 ROWLAND BAGNALL 42 FRANK KUPPNER 10 EDMUND BLUNDEN 29 GABRIEL LEVIN 11 NINA BOGIN 30 JENNY LEWIS 23 ALISON BRACKENBURY 33 THOMAS MCCARTHY 41 BEVERLEY BIE BRAHIC 9 CHRIS MCCULLY 13 LUCY BURNETT 45 CHRISTINE MARENDON 6 VAHNI CAPILDEO 43 ROD MENGHAM 26 MILES CHAMPION 5 STANLEY MOSS 48 FRED D’AGUIAR 7 LEONARD NOLENS 28 JANE DRAYCOTT 21 JEREMY OVER 50 MICHAEL EDWARDS 35 WALTER PATER 15 REBECCA ELSON 17 PROPERTIUS 16 PHILIP FRENCH 24 FREDERIC RAPHAEL 8 ISABEL GALLEYMORE 38 ARTHUR RIMBAUD 19 PERE GIMFERRER 39 GEORGE SEFERIS 20 REBECCA GOSS 40 PHILIP TERRY 22 JOHN GREENING 46 CHARLES TOMLINSON 27 MARILYN HACKER 36 HELEN TOOKEY 49 JOHN HEATH-STUBBS 14 CHRIS WALLACE-CRABBE 12 A. C. JACOBS 25 JOHN WILKINSON 32 FAWZI KARIM 31 WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS 18 LISA KELLY 47 JANE YEH 37 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR ‘What is a classic?’ Sainte-Beuve asked this ‘delicate question’ and answered with piety: it is a work which ‘reconciles us with mankind and with ourselves’. T.S. Eliot, answering the same question in 1944, as World War II was ending, talks about ‘maturity’ and raises Virgil onto a tremendous pedestal, observable from every latitude. His was a doomed attempt to revive in cultural terms a vision of a single-hearted Europe, and a Christian Europe at that. J.M. Coetzee is just one of the many critics to shoot Eliot down for what is not his best essay, though its nostalgia has a kind of resonance. Carcanet is busy re-inventing its Classics list. -

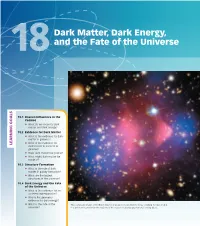

Dark Matter, Dark Energy, and the Fate of the Universe 461

Dark Matter, Dark Energy, 18 and the Fate of the Universe LS 18.1 Unseen Influences in the OA Cosmos G • What do we mean by dark matter and dark energy? NG I 18.2 Evidence for Dark Matter • What is the evidence for dark ARN matter in galaxies? E What is the evidence for L • dark matter in clusters of galaxies? • Does dark matter really exist? • What might dark matter be made of? 18.3 Structure Formation • What is the role of dark matter in galaxy formation? • What are the largest structures in the universe? 18.4 Dark Energy and the Fate of the Universe • What is the evidence for an accelerating expansion? • Why is flat geometry evidence for dark energy? • What is the fate of the This composite image of the Bullet Cluster of galaxies shows that the X-ray–emitting hot gas (red) is universe? in a different location from the majority of the mass revealed by gravitational lensing (blue). M18_BENN8083_CH18_pp458-487.indd 460 10/18/13 5:54 PM ver the past several chapters, we have discussed the strong Essential Preparation evidence supporting our scientific understanding of the 1. What determines the strength of gravity? history of the universe. This evidence indicates that our O [Section 4.4] universe was born about 14 billion years ago in the Big Bang and 2. How does Newton’s law of gravity extend Kepler’s has been expanding ever since. However, in regions that began with laws? [Section 4.4] slightly enhanced density, gravity took hold and built galaxies, within 3. -

Report for the Academic Years 1987-88 and 1988-89

The Institute for Advanced Study Annual Report 1986/87 I The Institute for Advanced Study I Annual Report for the Fiscal Year Julyl, 1986-June30, 1987 The Institute for Advanced Study Olden Lane Princeton, New Jersey 08540 U.S.A. Printed by Princeton University Press It is fundamental to our purpose, and our Extract from the letter addressed by the express desire, that in the appointments to the Founders to the Institute's Trustees, staff and faculty, as well as in the admission dated June 6, 1930, Newark, New Jersey. ofivorkers and students, no account shall be taken, directly or indirectly, of race, religion or sex. We feel strongly that the spirit characteristic of America at its noblest, above all, the pursuit of higher learning, cannot admit of any conditions as to personnel other than those designed to promote the objects for which this institution is established, ami particularly with )io regard 'whatever to accidents of race, creed or sex. f^-s^9 Table of Contents Trustees and Officers Founders Caroline Bamberger Fuld Louis Bamberger Board of Trustees John F. Akers T. D. Lee President ami University Professor Chief Executive Officer Columbia University IBM Corporation Elizabeth J. McCormack Daniel Bell Associate Henry Ford II Professor Rockefeller Family and Associates of Social Sciences Harvard University G. Daniel Mostow Henry Ford II Professor Thornton F. Bradshaw of Mathematics Consultant Yale University RCA Martin E. Segal Charles L. Brown Chairman Princeton, New Jersey Martin E. Segal Company Fletcher L. Byrom Zeph Stewart Carefree, Colorado Director The Center for Hellenic Studies Gladys K. Delmas Washington, D.C. -

Astrophysics in 1999

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Astrophysics in 1999 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1jb99011 Journal Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 112(770) ISSN 0004-6280 Authors Trimble, V Aschwanden, MJ Publication Date 2000 DOI 10.1086/316546 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PUBLICATIONS OF THE ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF THE PACIFIC, 112:434È503, 2000 April ( 2000. The Astronomical Society of the PaciÐc. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. Invited Review Astrophysics in 1999 VIRGINIA TRIMBLE Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742; and Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697 AND MARKUS J. ASCHWANDEN Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory, Department L941, Building 252, 3251 Hanover Street, Palo Alto, CA 94304 Received 1999 December 7; accepted 1999 December 7 ABSTRACT. The year 1999 saw the arrival of a star with three planets, a universe with three parameters, and a solar corona that could be heated at least three ways. In addition, there were at least three papers on every question that has ever been asked in astrophysics, from ““ Will the Universe expand forever? ÏÏ to ““ Does mantle convection occur in one or two layers? ÏÏ The answers generally were, ““ Yes,ÏÏ ““ No,ÏÏ and ““ None of the above,ÏÏ to each of the questions. The authors have done their best to organize the richness around centers deÐned by objects, methods, and madnesses. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. -

A Coat of Ashes Poetry, Daoism, Physics and Systems Theory

A coat of ashes A collection of poems, incorporating a metafictional narrative and Poetry, Daoism, physics and systems theory: a poetics A set of critical essays This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Janet Ruth Jackson Edith Cowan University School of Arts and Humanities 2018 Abstract This thesis comprises a book-length creative work accompanied by a set of essays. It explores how poetry might bring together spiritual and scientific discourses, focusing primarily on philosophical Daoism (Taoism) and contemporary physics. Systems theory (the science of complex and self-organising systems) is a secondary focus of the creative work and is used metaphorically in theorising the writing process. The creative work, “A coat of ashes”, is chiefly concerned with the nature of being. It asks, “What is?”, “What am I?” and, most urgently, “What matters?”. To engage with these questions, it opens a space in which voices expressing scientific and spiritual worldviews may be heard on equal terms. “A coat of ashes” contributes a substantial number of poems to the small corpus of Daoist-influenced poetry in English and adds to the larger corpus of poetry engaging with the sciences. The poems are offset by a metafictional narrative, “The Dream”, which may be read as an allegory of the writing journey and the struggle to combine discourses. The four essays articulate the poetics of “A coat of ashes” by addressing its context, themes, influences, methodology and compositional processes. They contribute to both literary criticism and writing theory. Like the creative work, they focus on dialogues between rationalist or scientific discourses and subjective or spiritual ones.