Documenting and Disseminating Agricultural Indigenous Knowledge for Sustainable Food Security in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tororo Profile.Indd

Tororo District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 TORORO DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE a Acknowledgment On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of a comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Odong Martin, DisasterM anagement Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/ DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to the Tororo District team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees TORORO DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The multi-hazard vulnerability profile output from this assessment was a combination of spatial modeling using socio-ecological spatial layers (i.e. DEM, Slope, Aspect, Flow Accumulation, Land use, vegetation cover, hydrology, soil types and soil moisture content, population, socio-economic, health facilities, accessibility, and meteorological data) and information captured from District Key Informant interviews and sub-county FGDs using a participatory approach. -

33 Years of Development 1986 – 2019

UGANDA BUREAU OF STATISTICS ENHANCING DATA QUALITY AND USE LIBERATION DAY CELEBRATIONS JANUARY 26, 2019, TORORO DISTRICT National Theme: Victory Day Anniversary: A Moment of Glory that set a new Chapter for a United, Peaceful and Prosperous Uganda 33 YEARS OF DEVELOPMENT 1986 – 2019 Understanding the Journey through Statistics ugstats @statisticsug Uganda Bureau of Statistics www.ubos.org LIBERATION DAY CELEBRATIONS JANUARY 26, 2019, TORORO DISTRICT GUEST OF HONOUR: H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, President of the Republic of Uganda Preamble “The Liberation Day is celebrated country-wide every January 26, of the year. The day commemorates and salutes the contribution of selfless citizens who engineered the Country’s Liberation Movement climaxing into a new Government in 1986 and the progress made ever since to date. ” It is therefore our pleasure to share with you the selected statistical indicators across sectors highlighting the nation’s growth & recovery paths over the years since 1986. H.E Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda Congratulatory message The Board of Directors, Management and Staff of the Uganda Bureau of Statistics congratulate His Excellency the President of the Republic of Uganda Yoweri Kaguta Museveni and the entire people of Uganda on this occasion of celebrating the 33rd Liberation Day anniversary. As we join the rest of the country in the celebration, we take the honour to salute all patriotic Ugandans in their desirous and selfless efforts geared towards sustaining the victory and gains of the Liberation Movement. In the same spirit, we commit ourselves to continuously deliver on our mandate of producing and disseminating quality official statistics for continuous and sustainable national Development. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

1. Introduction

1. Introduction 1.1 Background to the Case Study This report presents a case study on bicycles, women and rural transport in Uganda. It is the result of field work carried out in the Mbale and Tororo districts of eastern Uganda during a three-week visit in September 1991. The case study forms part of the Rural Travel and Transport Project (RTTP) of the World Bank- financed Sub-Saharan Africa Transport Program (SSATP), a major research program covering transport in SSA. One aspect of this program is the RTTP, which is designed to focus on transport at the level where it has the most direct influence on economic (particularly agricultural) and social development in rural areas of SSA. One of the key aims of the RTTP is to recommend approaches to the improvement of rural transport services, and to the adoption of intermediate technologies to increase personal mobility and agricultural production. This research is being conducted through Village-Level Transport and Travel Surveys (VLTTS) and related case studies. The World Bank has commissioned the International Labor Organization, in collaboration with I.T. Transport, to execute the VLTTS and the related case studies under the RTTP. 1.2 General Objectives of the Case Study The objective of the case study is to investigate two key aspects of rural mobility and accessibility focusing on: (i) The role of intermediate means of transport (IMT) in improving mobility, and the institutional and implementation policy requirements necessary for developing the use of IMT; and (ii) The role of transport in women's daily lives, - given that a major part of the transport burden falls on women in addition to their substantial agricultural and domestic responsibilities, and the impact of improvements in mobility and accessibility upon women. -

(4) of the Constitution Providing for Creation of New Counties

AMMENDED MOTTON FOR RESOLUTTON OF PARLTAMENT UNDER ARTTCLE 179 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION PROVIDING FOR CREATION OF NEW COUNTIES WHEREAS, Ariicle 179 (a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ugondo (os omended) provides for the criterio for olterotion of boundories oflor creotion of Administrotive Units including new Counties; AND WHEREAS Section 7 (7) of the Locql Governments Act Cop. 243, (os omended) empowers Porlioment to opprove olternotion of Boundories of/or creotion of o new County; Honoroble Colleogues willTHUS, recoll thot on Tuesdoy 30rn June, 2020,1 moved o motion on the floor of Porlioment for creotion of I5 (Fitteen) Counties thot were opproved by Cobinet hoving received requests from the District Councils of; Kiboole, Kotokwi, Agogo, lsingiro, Kisoro, Nokoseke, Kibogo, Buhweju, Lomwo, Kokumiro, Nokopiripirit, Mubende, Kwonio, Tororo ond Jinjo to creote the following Counties: - l) Buyanja Eost County out of Buyanjo County in Kibaale Distric[ 2) Ngoriom Covnty out of Usuk County in Kotakwi; 3) Agago Wesf County out of Agogo County in Agogo District; 4) Bukonga Norfh County out of Bukongo County in lsingiro District; 5) Bukimbiri County out of Bufumbira County in Kisoro District; 6) Nokoseke Centrol County out of Nokoseke Norfh County in Nokoseke Disfricf 7) Kibogo Wesf County out of Kibogo Eost County in Kbogo District; B) Buhweju West County aut of Buhweju County in Buhweju District; 9) Palobek County out of Lamwo County in Lamwo District; lA)BugongoiziSouth County out of BugongoiziWest County in Kokumiro Districf; I l)Chekwi Eosf County out of Chekwi County in Nokopiripirit District; l2)Buweku/o Soufh County out of Buweku/o County in Mubende Disfricf, l3)Kwanio Norfh County out of Kwonio Counfy in Kwonio Dislricf l )West Budomo Central County out of Wesf Budomo County inTororo Districf; l5)Kogomo Norfh County out of Kogomo County in Jinjo Districf. -

Elgon Investment Profile 2018

ELGON INVESTMENT PROFILE 2018 BULAMBULI KWEEN KAPCHORWA BUKWO SIRONKO BUDUDA MBALE KENYA MANAFWA Elgon Investment Profile A Sipi Falls in Kapchorwa B Elgon Investment Profile Background Information This is an Economic region The two sub regions have deriving its name from the dominant cooperative unions Mt. Elgon on whose slopes through which most of their the region is situated and is economic activities are comprised of the Bugisu districts centered, that is, the Bugisu of Mbale, Sironko, Manafwa, Cooperative Union and the Bududa and Bulambuli and the Sebei Cooperative Union. Sebei districts of Kapchorwa, The region is well known for Kween and Bukwo. The region its Arabica Coffee which is is located in Eastern Uganda mainly grown, processed and with Mbale the principal town marketed through these two located about 245 km from cooperative unions. Kampala. The region borders Kenya which can be accessed The region has a unique climate through Suam border post in pattern which favors special Bukwo district and Lwakhaka crops such as wheat, barley and border post in Manafwa. It other cereals like maize, and neighbors the Karamoja, Teso sorghum used in commercial and Bukedi regions internally. beer production. This plus the high tourism potential Three groups populate the derived from the Mountain Mount Elgon region, all highly and its associated ecosystems dependent on the forest make the Elgon region a high ecosystem: the Bagisu, the economic potential region. Sabiny, and a small group of The main town Mbale has historically forest-dwelling a gazetted industrial and and forest dependent upland business park whose activities Sabiny known as the Benet. -

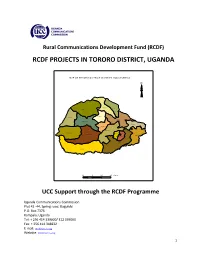

Rcdf Projects in Tororo District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN TORORO DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F T O RO R O D IS TR IC T S HO W IN G S U B C O U NTIES N M eriki t M olo Paya Petta Kire wa M ukuj u Nago ng er a Kwap a Kisoko Rubo ng i Nabu yog a Easter n Divisio n M ula nd a M ella W estern Division Osuku ru Iyo lwa 20 0 20 40 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..……..……3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……………4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….……….…..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Tororo district………….……..…….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Tororo district………..………………….………...……..….14 10- Map of Tororo district showing sub counties………..…………………….…….….15 11- Table showing the population of Tororo district by sub counties……..…...15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Tororo district…………………………………….…….……..16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. -

Adoption and Impact of SG 2000 - Uganda Crop Productivity Enhancing Technologies in Tororo, Buikwe and Kamwenge Districts of Uganda

Adoption and Impact of SG 2000 - Uganda Crop Productivity Enhancing Technologies in Tororo, Buikwe and Kamwenge Districts of Uganda Report By Frances Nakakawa and Ramzy Magambo Monitoring, Evaluation, Learning and Sharing Theme ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors acknowledges financial and technical support from Directors and staff of SG 2000 - Uganda; District Production Coordinators, SG 2000 – Uganda District Coordinators, Extension Agents (EAs), Community Based Facilitators (CBFs), host farmers of SG 2000 – Uganda demonstrations and other farmers from Tororo, Buikwe and Kamwenge Districts for their cooperation during field data capture is immensely gratified. We appreciate the contribution of enumerators and data entry technicians, and the core research team in capturing, cleaning and managing data for this report. ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS BDS Business Development Services CBF Community Based Facilitators CGDs Community Group Discussions CPE Crop Productivity and Enhancement CVP Community Variety Plots DIFA District Farmers’ Association EA Extension Agents FLPs Farmer Learning Platforms INSETT Innovations for Technical and Economic Transformation NARO National Agricultural Research Organization PTP Production Test Plot SACCO Savings and Credit Savings Organizations SG 2000 Sasakawa Global 2000 SPSS Statistical Package for Social Scientists TOP Technology Option Plot WAD Women Assisted Demonstration EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The objective of this study was to analyze the impact of improved seed varieties, fertilizer use and line planting technologies on farming outcomes. Both quantitative and qualitative methodologies were used to examine the bearings of the interventions. The bulk of the data was collected using formal survey techniques based on 375 structured questionnaires. A supplemental participatory qualitative approach was used by covering the three Districts of Tororo, Buikwe and Kamwenge, as well as a multi-stage, purposive and random sampling procedure on selected sub-counties and households. -

Nationally Threatened Species for Uganda

Nationally Threatened Species for Uganda National Red List for Uganda for the following Taxa: Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Butterflies, Dragonflies and Vascular Plants JANUARY 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research team and authors of the Uganda Redlist comprised of Sarah Prinsloo, Dr AJ Plumptre and Sam Ayebare of the Wildlife Conservation Society, together with the taxonomic specialists Dr Robert Kityo, Dr Mathias Behangana, Dr Perpetra Akite, Hamlet Mugabe, and Ben Kirunda and Dr Viola Clausnitzer. The Uganda Redlist has been a collaboration beween many individuals and institutions and these have been detailed in the relevant sections, or within the three workshop reports attached in the annexes. We would like to thank all these contributors, especially the Government of Uganda through its officers from Ugandan Wildlife Authority and National Environment Management Authority who have assisted the process. The Wildlife Conservation Society would like to make a special acknowledgement of Tullow Uganda Oil Pty, who in the face of limited biodiversity knowledge in the country, and specifically in their area of operation in the Albertine Graben, agreed to fund the research and production of the Uganda Redlist and this report on the Nationally Threatened Species of Uganda. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREAMBLE .......................................................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................... -

The Mineral Industry of Uganda in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook UGANDA [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior March 2021 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of Uganda By Thomas R. Yager In 2016, the East African country of Uganda accounted for Production 4% of the world’s mine production of pumice and pumicite. In recent years, the country also produced aggregates, brick In 2016, the output of vermiculite increased by 199%; clay, cement, refined cobalt, gold, iron ore, kaolin, refined lead, tungsten, by 17%; kaolin, by 13%; and pozzolanic materials limestone, niobium (columbium), salt, steel, tantalum, tin, (pumice and pumicite), by 11%. Niobium (columbium) and tungsten, and vermiculite. Uganda was not a globally significant tantalum production also increased sharply, and beryl, copper, consumer of most minerals in 2016; it is likely that domestic and dimension stone (marble) mining restarted in 2016. Iron ore consumption of pumice and pumicite (including pozzolanic production decreased by 76% in 2016, and that of tin, by 54% materials) in cement production and other construction uses was (Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2017, p. 196). Data on mineral globally significant (Crangle, 2018). production are in table 1. The mineral sector of Uganda, except for the petroleum Structure of the Mineral Industry and natural gas subsector, is governed by the Mining Act (2003). The petroleum and natural gas subsector is governed Most of Uganda’s mining and mineral-processing facilities by the Petroleum (Exploration, Development, and Production) were privately owned, including the cement and steel plants, Bill 2012 (the Upstream Act) and the Petroleum (Refining, the lead refinery, and the vermiculite mine. -

Tororo District Local Government Councils' Scorecard FY 2018/19

tororo DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 tororo DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 L-R: Ms. Rose Gamwera, Secretary General ULGA; Mr. Ben Kumumanya, PS. MoLG and Dr. Arthur Bainomugisha, Executive Director ACODE in a group photo with award winners at the launch of the 8th Local Government Councils Scorecard Report FY 2018/19 at Hotel Africana in Kampala on 10th March 2020 1.0 Introduction the northwest. The district was originally created from part of the Greater Maluku, to This brief was developed from the form Bukedi District that changed to Tororo scorecard report titled, “The Local in 1980. The district has since then altered Government Councils Scorecard in size giving birth to several districts. FY2018/19. The Next Big Steps: At the time of assessment, the current Consolidating Gains of Decentralisation district comprised 19 sub counties and and Repositioning the Local Government 1 municipality. Tororo has had a steadily Sector in Uganda.” The brief provides key increasing population of about 2.7% per highlights of the performance of elected annum. In 2012, the mid-year population leaders and Council of Tororo District was estimated at 487,900 (UBOS, 2012). Local Government during FY 2018/19. Tororo District is multi-ethnic with tribes 1.1 Brief about Tororo District including the Jopadhola, Itesots, Bagishu, Samia, as well as the Kenyan Nandi. Located in the Eastern part of the country, Tororo District is bordered by Mbale 1.2 The Local Government Councils District -

DIIS2004-01.Pdf

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Munk Ravnborg, Helle et al. Working Paper Gendered district poverty profiles and poverty monitoring Kabarole, Masaka, Pallisa, Rakai and Tororo districts, Uganda DIIS Working Paper, No. 2004:1 Provided in Cooperation with: Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen Suggested Citation: Munk Ravnborg, Helle et al. (2004) : Gendered district poverty profiles and poverty monitoring Kabarole, Masaka, Pallisa, Rakai and Tororo districts, Uganda, DIIS Working Paper, No. 2004:1, Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/84506 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made