Intimate Converse in Baker Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER the Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER The Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE opinions expressed are the editor’s unless noted otherwise no. 169 29th April 1997 To renew your subscription, send 12 stamped, self-addressed material and for amateur theatre companies who will be able to envelopes or (overseas) send 12 International Reply Coupons or assess the style and complexity of the material available to £5.50 or US$11.00 for 12 issues. Dollar checks should be them.’ 70 plays are covered in all. This first, limited edition of payable to Jean Upton. Dollar prices quoted without 150 copies is issued as a tribute to the late Peter Blythe. It comes qualification refer to US dollars. as two attractive A5 booklets, totalling 112 pages, a bargain at £6.00 including postage. (Buy this book and you can have the Helene Hanff died on the 9th April, aged 80. Before the equally recommended Sherlock Holmes and Sir Arthur Conan unexpected success of 84 Charing Cross Road , her most popular Doyle in Edinburgh for only £2.50.) contribution was to the Ellery Queen television series of the 1950s, but her love affair with a London bookshop epitomised Several authors have written of present-day detectives putting the literate American’s fascination with literary London. the principles of Sherlock Holmes into practice. Raymond Kay Lyon comes pretty near the top with The Sherlock Effect (Alibi Our Society has commissioned a First Day Cover for the ‘Tales Books, 40 High Street, Orwell, Royston, Herts. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

December 2016: Early Morning Alaskapublic.Org

schedule available online: December 2016: Early Morning alaskapublic.org 12:00am 12:30am 1:00am 1:30am 2:00am 2:30am 3:00am 3:30am 4:00am 4:30am Emery Antiques Roadshow: Thu 12/1 Inspire Happiness To Catch a Comet Passing On Blagdon Austin, TX (pt. 2) NOVA: Alien Planets Fri 12/2 Masterpiece Mystery! Sherlock - The Reichenbach Fall Masterpiece Mystery! Sherlock - The Empty Hearse Revealed Sat 12/3 Charlie Rose Highwaymen: Live at Nassau Coliseum Santana IV This Old House Hour Highwaymen: Live at Pearl Harbor - USS Washington Charlie Rose Sun 12/4 Eat to Live Katmai Nassau Coliseum (cont.) Oklahoma - The Final Story Week Week Emery Pearl Harbor - Into the Antiques Roadshow: Mon 12/5 Carpenters (cont.) BrainFit: 50 Ways to Grow Your Brain Blagdon Arizona Austin, TX (pt. 2) Antiques Roadshow: Antiques Roadshow: The Greeks: Cavemen to Secrets of Althorp - The Tue 12/6 To Catch a Comet Austin, TX (pt.3) Bismark, ND (pt.1) Kings Spencers Pearl Harbor - USS Pearl Harbor - Into the Frontline: The Secret The Greeks: Cavemen to Antiques Roadshow: Wed 12/7 Oklahoma - The Final Story Arizona History of ISIS Kings Bismark, ND (pt.1) Nature: Love in the Animal NOVA: Bombing Hitler's Antiques Roadshow: Pearl Harbor - USS Pearl Harbor - Into the Thu 12/8 Kingdom Supergun Austin, TX (pt.3) Oklahoma - The Final Story Arizona Sherlock Holmes: The Masterpiece Mystery! Sherlock - a Study in Masterpiece Mystery! Sherlock - The Blind NOVA: Bombing Hitler's Fri 12/9 Resident Patient Pink Banker Supergun Washington Charlie Rose First You Dream: The Music Antiques Roadshow: Sat 12/10 Hitmakers This Old House Hour Week Week of Kander & Ebb Bismark, ND (pt.1) Keeping Up As Time Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries: Midsomer Murders: Bad Masterpiece Mystery! Sherlock - The Great Bluegrass Sun 12/11 Appearances Goes By Murder in the Dark Tidings (pt. -

Sherlock III Ep3 FINAL Shooting Script

SHERLOCK III Episode 3 FINAL SHOOTING SCRIPT by STEVEN MOFFAT 09.09.13 EPISODE 3 BY STEVEN MOFFAT - FINAL SHOOTING SCRIPT - 09.09.13 1 BLACK SCREEN 1 A voice. Female, refined. LADY SMALLWOOD Mr. Magnussen, please state you full name for the record. MAGNUSSEN Charles Augustus Magnussen. Fading in on ... 2 INT. ENQUIRY ROOM - DAY 2 A government Enquiry. The strip-lit room, the horse-shoe table of MPs, facing the accused. The speaker is Lady Smallwood - fifties, wiry, sharp-eyed. The accused - calmly folded hands on a table top. Next to them, a pair of gold-rimmed spectacles. Magnussen. His voice is soft, reasonable, a Danish accent. LADY SMALLWOOD Mr. Magnussen, how would you describe your influence over the Prime Minister? MAGNUSSEN The British Prime Minster? LADY SMALLWOOD Any of the British Prime Ministers you have known. MAGNUSSEN I never had the slightest influence over any of them. Why would I? Lady Smallwood is consulting some notes. LADY SMALLWOOD I notice you’ve had seven meetings at Downing Street this year. Why? MAGNUSSEN Because I was invited. LADY SMALLWOOD Can you recall the subjects under discussion. MAGNUSSEN Not without being more indiscreet than I believe is appropriate. One of the MPs round the table - Garvie, bullish, self- righteous. (CONTINUED) 1. EPISODE 3 BY STEVEN MOFFAT - FINAL SHOOTING SCRIPT - 09.09.13 2 CONTINUED: 2 GARVIE Do you think it’s right that a newspaper proprietor - a private individual and in fact a foreign national - should have such regular access to our Prime Minister? On Magnussen’s clasped hands. -

The Baker Street Roommates: Friendship, Romance and Sexuality of Sherlock Holmes and John Watson in the Doyle Canon and BBC’S Sherlock

The Baker street roommates: Friendship, romance and sexuality of Sherlock Holmes and John Watson in the Doyle canon and BBC’s Sherlock. Riku Parviainen 682285A Bachelor’s Seminar and Thesis English Philology Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Spring 2020 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................... ................................................................................... 1 1. The Meeting ................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 The doctor and the detective ......................................................................................... 3 1.2 The detective’s past ....................................................................................................... 5 1.3 The meeting re-envisioned ....... ................................................................................... 7 2. Bachelor life at Baker street .......................................................................................... 9 2.1 Victorian friendship ...................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Watson: the incompetent partner?................................................................................. 11 2.3 Conflict at Baker street ................................................................................................. 14 3. Romance at Baker street ................................................................................................ -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2014

Jan 14 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) gathered in New York to celebrate the Great Detective's 160th birthday during the long weekend from Jan. 15 to Jan. 19. The festivities began with the traditional ASH Wednesday dinner sponsored by The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes at O'Casey's and continued with the Christopher Morley Walk led by Jim Cox and Dore Nash on Thursday morning, followed by the usual lunch at McSorley's. The Baker Street Irregulars' Distinguished Speaker at the Midtown Executive Club on Thursday evening was James O'Brien, author of THE SCIENTIFIC SHER- LOCK HOLMES: CRACKING THE CASE WITH SCIENCE & FORENSICS (2013); the title of his talk was "Reassessing Holmes the Scientist", and you will be able to read his paper in the next issue of The Baker Street Journal. The William Gillette Luncheon at Moran's was well attended, as always, and the Friends of Bogie's at Baker Street (Paul Singleton, Sarah Montague, and Andrew Joffe) entertained their audience with a tribute to an aged Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. The luncheon also was the occasion for Al Gregory's presentation of the annual Jan Whimsey Award (named in memory of his wife Jan Stauber) honoring the most whimsical piece in The Serpentine Muse last year; the winners (Susan Rice and Mickey Fromkin) received certificates and shared a check for the Canonical sum of $221.17. And Otto Penzler's tradi- tional open house at the Mysterious Bookshop provided the usual opportuni- ties to browse and buy. The Irregulars and their guests gathered for the BSI annual dinner at the Yale Club, where John Linsenmeyer proposed the preprandial first toast to Marilyn Nathan as The Woman. -

William S. Baring-Gould Was a Time Executive Whose Contributions to the Literary World (And Especially to Sherlockians) Are Manifest

Honorary Member, Emeritus photo courtesy of Bill Vande Water William Stuart Baring-Gould 1913-1967 William S. Baring-Gould was a Time executive whose contributions to the literary world (and especially to Sherlockians) are manifest. Mr. Baring-Gould was a descendent of the well-known author and archivist Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould (1834-1924) who was a featured character in Laurie King's book The Moor. He was the author of numerous important Sherlockian works including, Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, The Chronological Holmes and the famous The Annotated Sherlock Holmes. The Annotated Sherlock Holmes is considered by many Sherlockians as his crowning achievement and is a must in every Sherlock Holmes Collection. He authored other works, including The Lure of the Limerick: An Uninhibited History, Nero Wolfe of West Thirty-fifth Street (a work about the detective whom some speculate is the "son" of Sherlock Holmes) and collaborated with his wife, Ceil, onThe Annotated Mother Goose, Nursery Rhymes Old and New. All of these works are important volumes in their respective literary worlds. Mr. Baring-Gould was BSI and invested as "The Gloria Scott". Julian Wolfe said at his passing: "In the true Irregular tradition, and in accordance with the precepts of Christopher Morley, he was always ready to encourage young Sherlockians, many of whom owe much to his valuable asistance." Sherlockian.Net: William S. Baring-Gould Bill Baring-Gould, 1913-1967 W. S. Baring-Gould was an executive of Time Inc. and a distinguished though modest Sherlockian (invested in the Baker Street Irregulars as "The Gloria Scott", 1952). -

Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE E-Mail: [email protected] No

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE SHERLOCK HOLMES SOCIETY OF LONDON Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE e-mail: [email protected] no. 300 2nd February 2010 Welcome to the 300th issue! Thanks to Nicholas Briggs and his he did throw himself into local affairs as well, quickly becoming active colleagues at Big Finish (PO Box 3787, Maidenhead, Berkshire, SL6 in the Upper Norwood Literary & Scientific Society and Norwood 3TF; http://www.bigfinish.com/ranges/sherlock-holmes ) we can mark Cricket Club. He also, no less significantly, joined the Society for this anniversary with yet another prize competition. Two of you can win Psychical Research. Alistair Duncan is one of a distinguished little a copy of the third Big Finish Sherlock Holmes CD set, Holmes and the group whose work takes us just a little closer towards a complete Ripper by Brian Clemens, with Mr Briggs himself as the great portrait of the man who created Sherlock Holmes. He writes well, too. detective. (He had a very successful run in the same play a year ago at I’m delighted to recommend his book. the Theatre Royal, Nottingham.) Just name two films in which Sherlock MX Publishing has two special offers for members of the Sherlock Holmes investigates the Ripper murders. Send answers to me by 1 Holmes Society of London. You can buy all three of Alistair Duncan’s March, and the two correct answers drawn from the hat will win the books ( Eliminate the Impossible , Close to Holmes and The Norwood CDs. Holmes and the Ripper will be released in March, at £14.99. -

Ebsj-Sample.Pdf

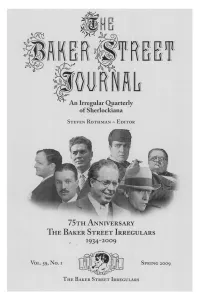

G E P4 \ e # An Irregular Quarterly of Sherlockiana STEVEN ROTHMAN EDITOR 75TH ANNIVERSARY THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS 1934-2009 - "I's- ti 0 VOL. 59, No I SPRING 2009 ;a. THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS Cover Illustration Key In honor of the 75th Anniversary of The Baker Street Irregulars our cover illustration features a montage of personalities who attended the very first dinner in 1934. 1. Christopher Morley; 2. H.W. Bell; 3. Vincent Starrett; 4. Basil Davenport; 5. Gene Tunney; 6. William Gillette; 7. Alexander Woollcott Volume 59 Number 1 Spring 2009 An Irregular Quarterly of Sherlockiana Founded by EDGAR W. SMITH Continued by JULIAN WOLFF, M.D. "Si monumentum quaeris, circumspice" Editor: STEVEN ROTHMAN Published by THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS Copyright 2009 by THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS All rights reserved LC 49-17066 ISSN 0005-4070 The appearance of the code following this statement indicates the copyright owner's consent that copies of articles in this journal may be made for personal or internal use, or for the personal internal use of specific clients. The consent is given on the condition, however, that the copier pay the stated per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 21 Congress Street, Salem, MA 01970, for copying beyond that permitted by law including sections 107 and 109 of the United States Copyright Act. This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying, such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale. Users should employ the following code when reporting copying from this issue to the Copyright Clearance Center: 0005 4070/91/$1.00 Articles in the JOURNAL are regularly indexed in Humanities International Complete (HIC). -

The Shaw One Hundred

The Basic Holmesian Library A Catalog by Timothy J. Johnson In conjunction with an exhibit based on John Bennett Shaw's list of One Hundred and a conference sponsored by The Norwegian Explorers of Minnesota Elmer L. Andersen Library Special Collections & Rare Books University of Minnesota Libraries June — July 2001 Minneapolis 2001 Introduction to the Exhibit “Some years ago I staged an exhibition of what I then considered to be the One Hundred Basic Books, pamphlets and periodicals relating to Sherlock Holmes.” So wrote John Bennett Shaw in a short introduction to his first official compilation of these books, pamphlets and periodicals, which he titled “The Basic Holmesian Library”. His goal was to give “an in-depth view of the entire Holmesian culture,” and while he admitted the difficulty encountered in choosing what to include out of so many fine writings, he approached this daunting task with the enthusiasm of one who truly understood the meaning of Collecting Sherlockiana. His own library, which he defined in his essay “Collecting Sherlockiana” as “…a number of books and other printed material on one subject, or on several,” focused on Sherlock Holmes. An avid bibliophile, he narrowed his collecting to this one subject after donating his other collections to such universities as Notre Dame, Tulsa, and the University of New Mexico. It is perhaps ironic to use the term narrowed for such a collection, which grew to over 15, 000 items. As his own library expanded with acquisitions of previously printed as well as newly published items, he revised his list of the Basic Holmesian Library. -

The Empty Hearse S

1 EXT. CEMETERY. DAY. 1 A stark black gravestone. Dead flowers wilted round the base, messages scrawled on damp cards. The ink has run. It’s like a shrine. The stone’s a bit grubby but the name in gold letters is unmistakable - SHERLOCK HOLMES A shadow falls across it... JOHN (V.O.) Sherlock!! CUT TO: 2 EXT. BART’S HOSPITAL ROOF. DAY. 2 ...flashback... SHERLOCK, phone in hand, stands on the roof of Bart’s. Below him, PASSERS-BY, a red phone-box, a parked laundry van... SHERLOCK (into phone) It’s a trick, John. Just a magic trick. CUT TO: Behind him, the dead body of JIM still lies, blood pooling around his shattered head. CUT TO: JOHN Stop it! John takes a step into the road. SHERLOCK Don’t! Don’t move. Stay right where you are. Keep your eyes fixed on me. I need you to do this for me. JOHN Do what? SHERLOCK This phone call. It’s my note. That’s what people do, isn’t it? Leave a note? 2. JOHN Leave a note when? SHERLOCK Goodbye, John. JOHN No - ! And Sherlock throws himself from the roof... JOHN (CONT’D) Sherlock!! John rushes across the street - and a CYCLIST slams into him. John’s hurled to the tarmac. The cyclist doesn’t stop. John doesn’t see what happens next... CUT TO: 3 INT. BART’S HOSPITAL. DAY. 3 Two MEN in black fatigues manhandle JIM’s corpse into a lift. Fast, ‘Mission Impossible’ style cuts. CUT TO: CLOSE on a contact lens holder.