What Is Multiple System Atrophy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive Dyskinesia Tardive Dyskinesia Checklist The checklist below can be used to help determine if you or someone you know may have signs associated with tardive dyskinesia and other movement disorders. Movement Description Observed? Rhythmic shaking of hands, jaw, head, or feet Yes Tremor A very rhythmic shaking at 3-6 beats per second usually indicates extrapyramidal symptoms or side effects (EPSE) of parkinsonism, even No if only visible in the tongue, jaw, hands, or legs. Sustained abnormal posture of neck or trunk Yes Dystonia Involuntary extension of the back or rotation of the neck over weeks or months is common in tardive dystonia. No Restless pacing, leg bouncing, or posture shifting Yes Akathisia Repetitive movements accompanied by a strong feeling of restlessness may indicate a medication side effect of akathisia. No Repeated stereotyped movements of the tongue, jaw, or lips Yes Examples include chewing movements, tongue darting, or lip pursing. TD is not rhythmic (i.e., not tremor). These mouth and tongue movements No are the most frequent signs of tardive dyskinesia. Tardive Writhing, twisting, dancing movements Yes Dyskinesia of fingers or toes Repetitive finger and toe movements are common in individuals with No tardive dyskinesia (and may appear to be similar to akathisia). Rocking, jerking, flexing, or thrusting of trunk or hips Yes Stereotyped movements of the trunk, hips, or pelvis may reflect tardive dyskinesia. No There are many kinds of abnormal movements in individuals receiving psychiatric medications and not all are because of drugs. If you answered “yes” to one or more of the items above, an evaluation by a psychiatrist or neurologist skilled in movement disorders may be warranted to determine the type of disorder and best treatment options. -

Rest Tremor Revisited: Parkinson's Disease and Other Disorders

Chen et al. Translational Neurodegeneration (2017) 6:16 DOI 10.1186/s40035-017-0086-4 REVIEW Open Access Rest tremor revisited: Parkinson’s disease and other disorders Wei Chen1,2, Franziska Hopfner2, Jos Steffen Becktepe2 and Günther Deuschl1,2* Abstract Tremor is the most common movement disorder characterized by a rhythmical, involuntary oscillatory movement of a body part. Since distinct diseases can cause similar tremor manifestations and vice-versa,itischallengingtomakean accurate diagnosis. This applies particularly for tremor at rest. This entity was only rarely studied in the past, although a multitude of clinical studies on prevalence and clinical features of tremor in Parkinson’s disease (PD), essential tremor and dystonia, have been carried out. Monosymptomatic rest tremor has been further separated from tremor-dominated PD. Rest tremor is also found in dystonic tremor, essential tremor with a rest component, Holmes tremor and a few even rarer conditions. Dopamine transporter imaging and several electrophysiological methods provide additional clues for tremor differential diagnosis. New evidence from neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies has broadened our knowledge on the pathophysiology of Parkinsonian and non-Parkinsonian tremor. Large cohort studies are warranted in future to explore the nature course and biological basis of tremor in common tremor related disorders. Keywords: Tremor, Parkinson’s disease, Essential tremor, Dystonia, Pathophysiology Background and clinical correlates of tremor in common tremor re- Tremor is defined as a rhythmical, involuntary oscillatory lated disorders. Some practical clinical cues and ancillary movement of a body part [1]. Making an accurate diagnosis tests for clinical distinction are found [3]. Besides, accu- of tremor disorders is challenging, since similar clinical mulating structural and functional neuroimaging, as well entities may be caused by different diseases. -

Diagnostic Clues in Multiple System Atrophy

DO I:10.4274/Tnd.82905 Case Report / Olgu Sunumu Diagnostic Clues in Multiple System Atrophy: A Case Report and Literature Review Multisistem Atrofi Tanısında İpuçları: Bir Olgu Sunumu ve Literatürün Gözden Geçirilmesi Mehmet Yücel, Oğuzhan Öz, Hakan Akgün, Semai Bek, Tayfun Kaşıkçı, İlter Uysal, Yaşar Kütükçü, Zeki Odabaşı Gülhane Military Medical Academy, Ankara, Turkey Sum mary Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is an adult-onset, sporadic, progressive neurodegenerative disease. Based on the consensus criteria, patients with MSA are clinically classified into cerebellar (MSA-C) and parkinsonian (MSA-P) subtypes. In addition to major diagnostic criteria including poor response to levodopa, and presence of pyramidal or cerebellar signs (ataxia) or autonomic failure, certain clinical features or ‘‘red flags’’ may raise the clinical suspicion for MSA. In our case report we present a 67-year-old female patient admitted to our hospital due to inability to walk, with poor response to levodopa therapy, whose neurological examination revealed severe Parkinsonism, ataxia and who fulfilled all criteria for MSA, as rarely seen in clinical practice.(Turkish Journal of Neurology 2013; 19:28-30) Key Words: Multiple system atrophy, autonomic failure, diagnostic criteria Özet Multisistem atrofi (MSA) erişkin dönemde başlayan, ilerleyici, nedeni bilinmeyen sporadik nörodejeneratif bir hastalıktır. MSA kabul görmüş tanı kriterlerine göre klinik olarak serebellar (MSA-C) ve parkinsoniyen (MSA-P) alt tiplerine ayrılmaktadır. Düşük levadopa yanıtı, piramidal, serebellar bulguların (ataksi) ya da otonomik bozukluk olması gibi majör tanı kriterlerininin yanında “red flags” olarak isimlendirilen belirgin klinik bulgular ya da uyarı işaretlerinin olması MSA tanısı için klinik şüpheyi oluşturmalıdır. Olgu sunumunda 67 yaşında yürüyememe şikayeti ile polikliniğimize müracaat eden ve levadopa tedavisine düşük yanıt gösteren ciddi parkinsonizm bulguları ile ataksi bulunan kadın hasta MSA tanı kriterlerini tam olarak karşıladığı ve klinik pratikte nadir görüldüğü için sunduk. -

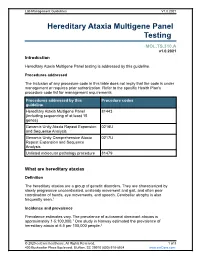

Hereditary Ataxia Multigene Panel Testing

Lab Management Guidelines V1.0.2021 Hereditary Ataxia Multigene Panel Testing MOL.TS.310.A v1.0.2021 Introduction Hereditary Ataxia Multigene Panel testing is addressed by this guideline. Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedures addressed by this Procedure codes guideline Hereditary Ataxia Multigene Panel 81443 (including sequencing of at least 15 genes) Genomic Unity Ataxia Repeat Expansion 0216U and Sequence Analysis Genomic Unity Comprehensive Ataxia 0217U Repeat Expansion and Sequence Analysis Unlisted molecular pathology procedure 81479 What are hereditary ataxias Definition The hereditary ataxias are a group of genetic disorders. They are characterized by slowly progressive uncoordinated, unsteady movement and gait, and often poor coordination of hands, eye movements, and speech. Cerebellar atrophy is also frequently seen.1 Incidence and prevalence Prevalence estimates vary. The prevalence of autosomal dominant ataxias is approximately 1-5:100,000.1 One study in Norway estimated the prevalence of hereditary ataxia at 6.5 per 100,000 people.2 © 2020 eviCore healthcare. All Rights Reserved. 1 of 8 400 Buckwalter Place Boulevard, Bluffton, SC 29910 (800) 918-8924 www.eviCore.com Lab Management Guidelines V1.0.2021 Symptoms Although hereditary ataxias are made up of multiple different conditions, they are characterized by slowly progressive uncoordinated, unsteady movement and gait, and often poor coordination of hands, eye movements, and speech. Cerebellar atrophy is also frequently seen.1 Cause Hereditary ataxias are caused by mutations in one of numerous genes. -

Multiple System Atrophy

Multiple System Atrophy U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service National Institutes of Health Multiple System Atrophy What is multiple system atrophy? ultiple system atrophy (MSA) is M a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a combination of symptoms that affect both the autonomic nervous system (the part of the nervous system that controls involuntary action such as blood pressure or digestion) and move- ment. The symptoms reflect the progressive loss of function and death of different types of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Symptoms of autonomic failure that may be seen in MSA include fainting spells and prob- lems with heart rate, erectile dysfunction, and bladder control. Motor impairments (loss of or limited muscle control or movement, or limited mobility) may include tremor, rigidity, and/or loss of muscle coordination as well as difficulties with speech and gait (the way a person walks). Some of these features are similar to those seen in Parkinson’s disease, and early in the disease course it often may be difficult to distinguish these disorders. MSA is a rare disease, affecting potentially 15,000 to 50,000 Americans, including men and women and all racial groups. Symptoms tend to appear in a person’s 50s and advance rapidly over the course of 5 to 10 years, with progressive loss of motor function and 1 eventual confinement to bed. People with MSA often develop pneumonia in the later stages of the disease and may suddenly die from cardiac or respiratory issues. While some of the symptoms of MSA can be treated with medications, currently there are no drugs that are able to slow disease progression and there is no cure. -

Clinical Manifestations of Essential Tremor

Journial of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 1972, 35, 365-372 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.35.3.365 on 1 June 1972. Downloaded from Clinical manifestations of essential tremor EDMUND CRITCHLEY From the Royal Infirmary, Preston SUMMARY A clinical study of 42 patients with essential tremor is presented. In the case of 12 patients the family history strongly suggested an autosomal dominant mode of transmission, in four the mode of inheritance was indeterminate, and the remaining 26 patients were sporadic cases without an established genetic basis. The tremor involved the upper extremities in 41 patients, the head in 25, lower limbs in 15, and trunk in two. Seven patients showed involvement of speech. Variations were found in the speed and regularity of the tremor. Leg involvement took a variety of forms: (1) direct involvement by tremor; (2) a painful limp associated with forearm tremor; (3) associated dyskinetic movements; (4) ataxia; (5) foot clubbing; and (6) evidence of peroneal muscular atrophy. Several minor symptoms hyperhidrosis, cramps, dyskinetic movements, and ataxia-were associated with essential tremor. Other features were linked phenotypically to the ataxias and system degenerations. Apart from minor alterations in tone, expression, and arm swing, features of Parkinsonism were notably absent. Protected by copyright. Essential tremor has been recognized as an or- much variation. It is occasionally present at rest ganic peculiarity of the nervous system, mimick- and inhibited by action, but is more usually de- ing neurotic and neural disorders with equal creased or absent at rest and present on volun- facility. Many synonyms-for example, benign, tary increase in muscle tonus, as in holding a limb hereditary, and senile tremor-describe its varied in a definite position (static, sustained-postural presentation. -

Part Ii – Neurological Disorders

Part ii – Neurological Disorders CHAPTER 14 MOVEMENT DISORDERS AND MOTOR NEURONE DISEASE Dr William P. Howlett 2012 Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, Moshi, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania BRIC 2012 University of Bergen PO Box 7800 NO-5020 Bergen Norway NEUROLOGY IN AFRICA William Howlett Illustrations: Ellinor Moldeklev Hoff, Department of Photos and Drawings, UiB Cover: Tor Vegard Tobiassen Layout: Christian Bakke, Division of Communication, University of Bergen E JØM RKE IL T M 2 Printed by Bodoni, Bergen, Norway 4 9 1 9 6 Trykksak Copyright © 2012 William Howlett NEUROLOGY IN AFRICA is freely available to download at Bergen Open Research Archive (https://bora.uib.no) www.uib.no/cih/en/resources/neurology-in-africa ISBN 978-82-7453-085-0 Notice/Disclaimer This publication is intended to give accurate information with regard to the subject matter covered. However medical knowledge is constantly changing and information may alter. It is the responsibility of the practitioner to determine the best treatment for the patient and readers are therefore obliged to check and verify information contained within the book. This recommendation is most important with regard to drugs used, their dose, route and duration of administration, indications and contraindications and side effects. The author and the publisher waive any and all liability for damages, injury or death to persons or property incurred, directly or indirectly by this publication. CONTENTS MOVEMENT DISORDERS AND MOTOR NEURONE DISEASE 329 PARKINSON’S DISEASE (PD) � � � � � � � � � � � -

The Clinical Approach to Movement Disorders Wilson F

REVIEWS The clinical approach to movement disorders Wilson F. Abdo, Bart P. C. van de Warrenburg, David J. Burn, Niall P. Quinn and Bastiaan R. Bloem Abstract | Movement disorders are commonly encountered in the clinic. In this Review, aimed at trainees and general neurologists, we provide a practical step-by-step approach to help clinicians in their ‘pattern recognition’ of movement disorders, as part of a process that ultimately leads to the diagnosis. The key to success is establishing the phenomenology of the clinical syndrome, which is determined from the specific combination of the dominant movement disorder, other abnormal movements in patients presenting with a mixed movement disorder, and a set of associated neurological and non-neurological abnormalities. Definition of the clinical syndrome in this manner should, in turn, result in a differential diagnosis. Sometimes, simple pattern recognition will suffice and lead directly to the diagnosis, but often ancillary investigations, guided by the dominant movement disorder, are required. We illustrate this diagnostic process for the most common types of movement disorder, namely, akinetic –rigid syndromes and the various types of hyperkinetic disorders (myoclonus, chorea, tics, dystonia and tremor). Abdo, W. F. et al. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 29–37 (2010); doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.196 1 Continuing Medical Education online 85 years. The prevalence of essential tremor—the most common form of tremor—is 4% in people aged over This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance 40 years, increasing to 14% in people over 65 years of with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council age.2,3 The prevalence of tics in school-age children and for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of 4 MedscapeCME and Nature Publishing Group. -

Lewy Body Diseases and Multiple System Atrophy As ␣-Synucleinopathies

Molecular Psychiatry (1998) 3, 462–465 1998 Stockton Press All rights reserved 1359–4184/98 $12.00 GUEST EDITORIAL Lewy body diseases and multiple system atrophy as ␣-synucleinopathies Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies synuclein are the first known genetic causes of Parkin- are among the most common neurodegenerative dis- son’s disease. They are located in the amino-terminal eases. They share the Lewy body and the Lewy neurite half of ␣-synuclein, which consists of seven imperfect as their defining neuropathological characteristics. repeats of 11 amino acids each, with the consensus Originally described in 1912 as a light-microscopic sequence KTKEGV (Figure 1). It has been suggested entity, the Lewy body was shown to be made of abnor- that ␣-synuclein may bind through these repeats to mal filaments in the 1960s. Over the past year, the bio- membranes rich in acidic phospholipids.3 chemical nature of the Lewy body filament has been This work raised the question whether ␣-synuclein revealed. is a component of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites of A large number of different proteins has been idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and of dementia with reported to be present in Lewy bodies and Lewy neur- Lewy bodies. Using well-characterised anti-␣-synuc- ites by immunohistochemical methods. However, these lein antibodies, Spillantini et al showed strong staining findings do not permit us to distinguish between of both Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in idiopathic intrinsic Lewy body components and normal cellular Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies.4 constituents that get merely trapped in the filaments They also reported the lack of staining of these patho- that make up the Lewy body. -

Tremor in Multiple System Atrophy – a Review

Freely available online Reviews Tremor in Multiple System Atrophy – a review 1 1 1* Christine Kaindlstorfer , Roberta Granata & Gregor Karl Wenning 1 Division of Neurobiology, Department of Neurology, Medical University Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria. Abstract Background: Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a rare neurodegenerative movement disorder characterized by a rapidly progressive course. The clinical presentation can include autonomic failure, parkinsonism, and cerebellar signs. Differentiation from Parkinson’s disease (PD) is difficult if there is levodopa- responsive parkinsonism, rest tremor, lack of cerebellar ataxia, or mild/delayed autonomic failure. Little is known about tremor prevalence and features in MSA. Methods: We performed a PubMed search to collect the literature on tremor in MSA and considered reports published between 1900 and 2013. Results: Tremor is a common feature among MSA patients. Up to 80% of MSA patients show tremor, and patients with the parkinsonian variant of MSA are more commonly affected. Postural tremor has been documented in about half of the MSA population and is frequently referred to as jerky postural tremor with evidence of minipolymyoclonus on neurophysiological examination. Resting tremor has been reported in about one-third of patients but, in contrast to PD, only 10% show typical parkinsonian ‘‘pill-rolling’’ rest tremor. Some patients exhibit intention tremor associated with cerebellar dysmetria. In general, MSA patients can have more than one tremor type owing to a complex neuropathology that includes both the basal ganglia and pontocerebellar circuits. Discussion: Tremor is not rare in MSA and might be underrecognized. Rest, postural, action and intention tremor can all be present, with jerky tremulous movements of the outstretched hands being the most characteristic. -

Primary Lateral Sclerosis Presenting Parkinsonian Symptoms Without

1768 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.2003.035212 on 16 November 2004. Downloaded from SHORT REPORT Primary lateral sclerosis presenting parkinsonian symptoms without nigrostriatal involvement N Mabuchi, H Watanabe, N Atsuta, M Hirayama, H Ito, H Fukatsu, T Kato, K Ito, G Sobue ............................................................................................................................... J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:1768–1771. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.035212 We encountered three patients with primary lateral sclerosis Patient 2 Frozen gait with initial hesitation developed at age 62, (PLS) showing bradykinesia, frozen gait, and severe postural followed by cramping in both legs during sleep at age 64. He instability, as well as slowly progressive spinobulbar began to experience speech disturbance with spastic dys- spasticity. Cranial magnetic resonance (MR) imaging showed arthria and bouts of unprovoked laughing and crying. He precentral gyrus atrophy. Central motor conduction was showed severe postural instability with occasional falling, markedly prolonged or failed to evoke a response. Positron especially backward, as well as akinesia. He could not stand emission tomography (PET) showed significant reduction of up or initiate walking smoothly. He also showed facial 18 [ F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake in the area of the hypokinesia with reduced blinking. All symptoms showed precentral gyrus extending to the prefrontal, medial frontal, gradual progression. and cingulate areas. No abnormalities were seen in the nigrostriatal system with PET using [18F]fluorodopa or 11 Patient 3 [ C]raclopride or with proton MR spectroscopy. Thus, Postural instability and gait disturbance were present by age widespread prefrontal, medial, and cingulate frontal lobe 68. He noted left arm clumsiness, and paucity of movement involvement can be associated with the parkinsonian gradually worsened and progressed to akinesia. -

EXTRAPYRAMIDAL MOVEMENT DISORDERS (GENERAL) Mov1 (1)

EXTRAPYRAMIDAL MOVEMENT DISORDERS (GENERAL) Mov1 (1) Extrapyramidal Movement Disorders (GENERAL) Last updated: July 12, 2019 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY ..................................................................................................................................... 1 CLINICAL FEATURES .................................................................................................................................... 2 DIAGNOSIS ................................................................................................................................................... 3 TREATMENT ................................................................................................................................................. 4 MORPHOLOGIC CORRELATIONS ................................................................................................................... 4 TREMOR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 ESSENTIAL TREMOR ..................................................................................................................................... 6 ORTHOSTATIC TREMOR ................................................................................................................................ 7 PRIMARY WRITER'S TREMOR ........................................................................................................................ 7 PHYSIOLOGIC TREMOR ................................................................................................................................