Making Room for Cooperative Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFLC V Conservancy

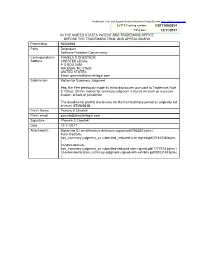

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA863914 Filing date: 12/11/2017 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 92066968 Party Defendant Software Freedom Conservancy Correspondence PAMELA S CHESTECK Address CHESTEK LEGAL P O BOX 2492 RALEIGH, NC 27602 UNITED STATES Email: [email protected] Submission Motion for Summary Judgment Yes, the Filer previously made its initial disclosures pursuant to Trademark Rule 2.120(a); OR the motion for summary judgment is based on claim or issue pre- clusion, or lack of jurisdiction. The deadline for pretrial disclosures for the first testimony period as originally set or reset: 07/20/2018 Filer's Name Pamela S Chestek Filer's email [email protected] Signature /Pamela S Chestek/ Date 12/11/2017 Attachments Motion for SJ on affirmative defenses-signed.pdf(756280 bytes ) Kuhn-Declara- tion_summary-judgment_as-submitted_reduced-size-signed.pdf(2181238 bytes ) Sandler-declara- tion_summary-judgment_as-submitted-reduced-size-signed.pdf(1777273 bytes ) Chestek declaration_summary-judgment-signed-with-exhibits.pdf(2003142 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD In the Mater of Registraion No. 4212971 Mark: SOFTWARE FREEDOM CONSERVANCY Registraion date: September 25, 2012 Sotware Freedom Law Center Peiioner, v. Cancellaion No. 92066968 Sotware Freedom Conservancy Registrant. RESPONDENT’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT ON ITS AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSES Introducion The Peiioner, Sotware Freedom Law Center (“SFLC”), is a provider of legal services. It had the idea to create an independent enity that would ofer inancial and administraive services for free and open source sotware projects. -

Toyota Activities for OSS Compliance

Toyota Activities for OSS Compliance Masato Endo Assistant Manager Connected Vehicle Group Intellectual Property Div. Toyota Motor Corporation Nov. 16, 2017, Open Compliance Summit © 2017 Toyota Motor Corporation 1 1.1. Expansion of OSS in the Automotive Sector Automotive sector Toyota products In the automotive sector, the number of OSS projects is growing rapidly, and some are already available on the market. Nov. 16, 2017, Open Compliance Summit © 2017 Toyota Motor Corporation 2 1.2. What is Automotive Grade Linux (AGL) AGL is a Linux Foundation project to develop an operating system for infotainment platforms. Nov. 16, 2017, Open Compliance Summit © 2017 Toyota Motor Corporation 3 1.3. AGL Members Ten global OEMs have joined the project. Many automotive industry suppliers and IT companies also contribute to AGL. Nov. 16, 2017, Open Compliance Summit © 2017 Toyota Motor Corporation 4 1.4. Recent AGL Activities AGL All Member Meeting Automotive Linux Summit (Feb 8 to Feb 10) (May 31 to June2) AGL holds many events to foster community engagement. These events include not only discussions of technical issues, but also of legal issues. Nov. 16, 2017, Open Compliance Summit © 2017 Toyota Motor Corporation 5 1.5. Toyota and AGL (1/5) 2011 Toyota joined the Linux Foundation. 1st ALS: Automotive Linux Summit (Yokohama, Japan) Nov. 16, 2017, Open Compliance Summit © 2017 Toyota Motor Corporation 6 1.6. Toyota and AGL (2/5) 2011 2012 2013 2014 Automotive Linux Summit 2014 (Tokyo, Japan) AGL Steering Committee Meeting: • AGL projects started and funded. Nov. 16, 2017, Open Compliance Summit © 2017 Toyota Motor Corporation 7 1.7. -

CLE Materials

Software Freedom Law Center Fall Conference at Columbia Law School CLE materials October 30, 2015 License Compliance Dispute Resolution Software Freedom Law Center October 30, 2015 1) Software Freedom Law Center: Guide to GPL Compliance 2nd Edition 2) Free Software Foundation: Principles for Community-Oriented GPL Enforcement 3) Terry J. Ilardi: FOSS Compliance @ IBM 15 Years (and count- ing) Software Freedom Law Center Guide to GPL Compliance 2nd Edition Eben Moglen & Mishi Choudhary October 31, 2014 Contents TheWhat,WhyandHowofGNUGPL . 3 CopyrightandCopyleft . 4 Concepts and License Mechanics of Copyleft. 6 LicenseProvisionsAnalyzed. 10 GPLv2............................... 10 GPLv3............................... 18 GPLSpecialExceptionLicenses . 31 AGPL............................... 31 LGPL ............................... 34 Understanding Your Compliance Responsibilities . 41 WhoHasComplianceObligations? . 41 HowtoMeetComplianceObligations . 43 TheKeytoComplianceisGovernance . 45 PrinciplesofPreparedCompliance . 47 HandlingComplianceInquiries . 48 Appendix1: OfferofSourceCode . 52 References................................ 56 This document presents the legal analysis of the Software Freedom Law Center and the authors. This document does not express the views, intentions, policy, or legal analysis of any SFLC clients or client organizations. This document does not constitute legal advice or opinion regarding any specific factual situation or party. Specific legal advice should always be sought from qualified legal counsel on the application -

Getting Humans to Do Quantum Optimization - User Acquisition, Engagement and Early Results from the Citizen Cyberscience Game Quantum Moves

Human Computation (2014) 1:2:221-246 © 2014, Lieberoth et al. CC-BY-3.0 ISSN: 2330-8001, DOI: 10.15346/hc.v1i2.11 Getting Humans to do Quantum Optimization - User Acquisition, Engagement and Early Results from the Citizen Cyberscience Game Quantum Moves ANDREAS LIEBEROTH, Aarhus University MADS KOCK PEDERSEN, Aarhus University ANDREEA CATALINA MARIN, Aarhus University TILO PLANKE, Aarhus University JACOB FRIIS SHERSON, Aarhus University ABSTRACT The game Quantum Moves was designed to pit human players against computer algorithms, combining their solutions into hybrid optimization to control a scalable quantum computer. In this midstream report, we open our design process and describe the series of constitutive building stages going into a quantum physics citizen science game. We present our approach from designing a core gameplay around quantum simulations, to putting extra game elements in place in order to frame, structure, and motivate players’ difficult path from curious visitors to competent science contributors. The player base is extremely diverse – for instance, two top players are a 40 year old female accountant and a male taxi driver. Among statistical predictors for retention and in-game high scores, the data from our first year suggest that people recruited based on real-world physics interest and via real-world events, but only with an intermediate science education, are more likely to become engaged and skilled contributors. Interestingly, female players tended to perform better than male players, even though men played more games per day. To understand this relationship, we explore the profiles of our top players in more depth. We discuss in-world and in-game performance factors departing in psychological theories of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and the implications for using real live humans to do hybrid optimization via initially simple, but ultimately very cognitively complex games. -

October 20, 2020 / Schedule *All Times Are Eastern Standard

The 2020 schedule is proudly sponsored and made possible by Google Open Source. October 20, 2020 / Schedule *All times are Eastern Standard. All Things Open is made possible by these sponsors Day Two of All Things Open 2020 will feature morning plenary keynotes as well as 45 minute sessions across 24 topic tracks. There is also a Featured Session block from PRESENTING 12:30 - 1:15 pm ET highlighting talks and topics we feel are widely applicable. SPONSORS 8:45AM - 9:00AM Welcome & Keynotes (Main Stage) Todd Lewis, All Things Open KEYNOTES (MAIN STAGE) 9:00AM - 9:15AM 10 Commandments of Navigating Code Reviews Angie Jones, Applitools 9:20AM - 9:35AM Security is Everyone’s Responsibility PLATINUM Marten Mickos, HackerOne SPONSORS 9:40AM - 10:00AM An Animated Guide to Vue 3 Reactivity and Internals Sarah Drasner, Netlify 10:05AM - 10:20AM Open Source Licenses at the Center Chris DiBona, Google 10:20AM - 10:30AM BREAK - NETWORKING/SPONSORS 10:30AM - 11:15AM Sessions (See Next Page) 11:15am - 11:30PM BREAK GOLD SPONSORS 11:30AM - 12:15PM Sessions (See Next Page) 12:15PM - 12:30PM BREAK 12:30PM - 1:15PM Featured Sessions (See Next Page) 1:15PM - 1:30PM BREAK 1:30PM - 2:15PM Sessions (See Next Page) 2:15PM - 2:30PM BREAK 2:30PM - 3:15PM Sessions (See Next Page) SILVER SPONSORS 3:15PM - 3:30PM BREAK 3:30PM - 4:15PM Sessions (See Next Page) 4:15PM - 4:30PM BREAK 4:30PM - 5:15PM Sessions (See Next Page) 5:15PM - 5:30PM Final comments and wrap-up (Main Stage) Todd Lewis, All Things Open BRONZE SPONSORS Commersetools hyper63 Confluent MySQL cprime Syncfusion Elastic TerminusDB Please note, minor changes to the schedule are possible prior to event date. -

News@UK the Newsletter of UKUUG, the UK’S Unix and Open Systems Users Group Published Electronically At

news@UK The Newsletter of UKUUG, the UK's Unix and Open Systems Users Group Published electronically at http://www.ukuug.org/newsletter/ Volume 17, Number 3 ISSN 0965-9412 September 2008 Contents News from the Secretariat 3 Chairman's report 3 LISA '08 announcement 4 OSCON 2008 5 Open Tech 2008 (1) 7 Open Tech 2008 (2) 8 Linux kernel resource allocation in virtualized environments 8 Fear and Loathing in the Routing System 10 Hardware review: Fujitsu Siemens Esprimo P2411 15 Book review: Java Pocket Guide 16 Book review: CakePHP Application Development 16 Book review: The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World 17 Book review: Intellectual Property and Open Source 18 Contributors 19 Contacts 20 news@UK UKUUG Newsletter News from the Secretariat Jane Morrison On 30th June UKUUG, in conjunction with O'Reilly, organised a successful tutorial on Moodle. This event was the first of many we hope to bring you in the future with UKUUG working alongside O'Reilly. Josette Garcia has access to many authors who can also be of interest to our membership by providing tutorials etc. OpenTech 2008 (organised by Council member Sam Smith), was an exceptional success with some 600 people attending. Two accounts of the event appear in this Newsletter. The 2008 event was so successful that plans are going forward for a similar event in early July 2009. The Linux event this year has been delayed to November and you should find enclosed in this Newsletter the provisional programme and booking information. On 26th November we are organising the OpenBSD's PF tutorial by Peter N M Hansteen. -

Safe Cities, the Smart Way

MAR / APR 2020 SAFE CITIES, THE SMART WAY In Focus In Focus Security Feature Security Feature How To Navigate Tips For Small Business Intrusion And A Ransomware Ransomware Cybersecurity Access Control: Recovery Protection On Threats And How The Perfect Pair For Process Windows Systems To Fix the Fox Facility Security SST COVER.indd 1 5/3/20 4:06 PM At GSX2020, thousands of executives and decision makers will be actively assessing the latest security technologies and solutions. of them don’t attend other events.* Let’s discuss how we can support your business development goals. SECURE YOUR BOOTH SPACE TODAY GSX.org/exhibit Untitled-2Untitled-4 1 8/1/205/3/20 9:553:11 AMPM Untitled-4 1 5/3/20 3:12 PM 2 CONTENT SECURITY SOLUTIONS TODAY IN THIS ISSUE 6 Calendar Of Events 8 Editor’s Note 10 In The News Updates From Asia And Beyond 32 Cover Story Cover Story Safe Cities, The Safe Cities, The Smart Way 32 | Smart Way 37 Security Feature + How Can A Digital Twin Create A Seamless Workplace For Employees? + How Businesses Need To Show How AI Decides + Small Business Cybersecurity Threats And How To Fix The Fox + Working Smarter: The Intelligent Office + Increasing Business ROI With IoT In Facilities Management + Check Point Software Fast Tracks Network Security With New Security Gateways Security Feature + Commercial Applications For Cutting-Edge Small Business Cybersecurity Threats And How to Fix the Fox Intrusion And Alarm Tech 37 | + Tech Trends: Put Radar On Your Radar + Lidar Comes Of Age In Security + Intrusion And Access Control: The Perfect -

Open Invention Network® Is an Intellectual Property Company That Was Formed to Promote Linux by Using Patents to Create a Collaborative Environment

Open Invention Network® is an intellectual property company that was formed to promote Linux by using patents to create a collaborative environment. It promotes a positive, fertile ecosystem for Linux, which in turns drives innovation and choice in the global marketplace. This helps ensure the continuation of innovation that has benefited software vendors, customers, emerging markets and investors. Open Invention Network® is refining the intellectual property model so that important patents are openly shared in a collaborative environment. Patents owned by Open Invention Network® are available royalty-free to any company, institution or individual that agrees not to assert its patents against the Linux System. This enables companies to make significant corporate and capital expenditure investments in Linux — helping to fuel economic growth. Open Invention Network® ensures the openness of the Linux source code, so that programmers, equipment vendors, ISVs and institutions can invest in and use Linux with less worry about intellectual property issues. Its licensees can use the company’s patents to innovate freely. This makes it economically attractive for companies that want to repackage, embed and use Linux to host specialized services or create complementary products. Open Invention Network® has considerable industry backing. It was launched in 2005, and has received investments from IBM, NEC, Novell, Philips, Red Hat and Sony. Keith Bergelt, Chief Executive Officer Keith Bergelt is the chief executive officer of Open Invention Network® (OIN), the collaborative enterprise that enables innovation in open source and an increasingly vibrant ecosystem around Linux. In this capacity he is directly responsible for enabling, influencing and defending the integrity of the Linux ecosystem. -

Volume 142 November, 2018 Firejail: Easy Sandbox on Pclinuxos

Volume 142 November, 2018 Firejail: Easy Sandbox On PCLinuxOS GIMP Tutorial: How To Apply A Sepia Tone Short Topix: Linux Is Changing The Face Of End-User Computing PCLinuxOS Family Member Spotlight: Martin Goose ANGRYsearch Microsoft Open Sources 60,000 Patents To Help Linux The Death Bell Tolls For G+ ms_meme's Nook: I Just Care For PCLinuxOS PCLinuxOS Recipe Corner: Mini Mozzarella Stuffed Turkey Zucchini Meatball Orechiette And more inside ... In This Issue... 3 From The Chief Editor's Desk 4 Firejail, Easy Sandbox On PCLinuxOS The PCLinuxOS name, logo and colors are the trademark of 7 Screenshot Showcase Texstar. 8 Short Topix: The PCLinuxOS Magazine is a monthly online publication containing PCLinuxOS-related materials. It is published Linux Is Changing The Face Of End-User Computing primarily for members of the PCLinuxOS community. The magazine staff is comprised of volunteers from the 15 GIMP Tutorial: How To Apply A Sepia Tone PCLinuxOS community. 17 Screenshot Showcase Visit us online at http://www.pclosmag.com 18 ms_meme's Nook: Booting From Both Sides This release was made possible by the following volunteers: 19 PCLinuxOS Family Member Spotlight: Martin Goose Chief Editor: Paul Arnote (parnote) Assistant Editor: Meemaw 21 Screenshot Showcase Artwork: Sproggy, Timeth, ms_meme, Meemaw Magazine Layout: Paul Arnote, Meemaw, ms_meme 22 Microsoft Open Sources Over 60,000 Patents HTML Layout: YouCanToo To Help Linux Staff: ms_meme CgBoy 23 Screenshot Showcase Meemaw YouCanToo Gary L. Ratliff, Sr. Pete Kelly 25 PCLinuxOS Recipe Corner Daniel Meiß-Wilhelm phorneker daiashi Khadis Thok 26 ANGRYsearch Alessandro Ebersol Smileeb 27 Screenshot Showcase Contributors: 28 The Death Bell Tolls For Google+ 30 ms_meme's Nook: I Just Care For PCLinuxOS 31 Screenshot Showcase The PCLinuxOS Magazine is released under the Creative 32 PCLinuxOS Bonus Recipe Corner Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share-Alike 3.0 Unported license. -

Keith Bergelt: the Case F Or Market Based Patent Ref

Keith Bergelt: The Case for Market Based Patent Reform Published: Friday, 6 Nov 2009 | 11:11 AM ET In the wake of the financial crisis and its attendant repercussions across the global economy, the U.S. Congress stands poised to address the issue of patent reform. Much debated and long anticipated, patent reform legislation is back under consideration with the bill possibly coming up for vote, prior to the end of 2009. Under the stewardship of a set of legislators well sensitized to the salient issues and with the thoughtful counsel of David Kappos, Keith Bergelt President Obama’s business savvy head of the U.S. Patent and CEO Open Invention Trademark Office (USPTO), the stars are aligning to usher in Network legislation that promises to offer significant advances in an arena that has been overdue for reform. During the debate that will shortly resume, critical patent system issues will be addressed. In addition to the legislative reform, the judiciary has been seeking to address the troubling emergence of non-practicing entities (NPEs) who acquire patents for the sole purpose of litigating those patents against deep-pocketed technology companies, for the purpose of securing damage awards or litigation avoidance settlements. Such NPEs have also been dubbed ‘patent trolls’ by the popular press because of their positioning as antagonists to true innovation. Cases such as eBay v. MercExchange have directly addressed the issue of NPEs by sharpening the standing requirement necessary to secure injunctions in patent infringement cases. Others, such as Bilski, have considered an altered standard of patentability that was largely ushered in by the initial USPTO grant and later validation of business method patents in the State Street bank case. -

Sewagudde D Phd Final 3005

Why did video screens get slimmer? A study of the role of Intellectual Property in the commercial development of organic light-emitting diodes Deborah Nabbosa Miriam Sewagudde Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Source: Gabworthy, 2015) I, Deborah Nabbosa Miriam Sewagudde, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 24th February 2017 Details of collaboration and publications: None i I would like to give all the glory and honour to the Almighty God, for not only inspiring me to do this but for providing the grace, provision, favour, wisdom, strength and resilience I needed to start and to finish well. -

The Playful Citizen Civic Engagement in Civic Engagement a Mediatized Culture Edited Glas, by René Sybille Lammes, Michiel Lange, De Raessens,Joost and Imar Vries De

GAMES AND PLAY Raessens, and Vries De (eds.) Glas, Lammes, Lange, De The Playful Citizen The Playful Edited by René Glas, Sybille Lammes, Michiel de Lange, Joost Raessens, and Imar de Vries The Playful Citizen Civic Engagement in a Mediatized Culture The Playful Citizen The Playful Citizen Civic Engagement in a Mediatized Culture Edited by René Glas, Sybille Lammes, Michiel de Lange, Joost Raessens, and Imar de Vries Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book was made possible by the Utrecht Center for Game Research (one of the focus areas of Utrecht University), the Open Access Fund of Utrecht University, and the research project Persuasive gaming. From theory-based design to validation and back, funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover illustration: Photograph of Begging For Change, MEEK (courtesy of Jake Smallman). Cover design: Coördesign Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 452 3 e-isbn 978 90 4853 520 0 doi 10.5117/9789462984523 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) All authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Contents 1. The playful citizen: An introduction 9 René Glas, Sybille Lammes, Michiel de Lange, Joost Raessens, and Imar de Vries Part I Ludo-literacies Introduction to Part I 33 René Glas, Sybille Lammes, Michiel de Lange, Joost Raessens, and Imar de Vries 2.