Firsts for Feminism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics, Art, and the Politics of Value in Twentieth-Century United States

The Subjects of Modernism: Mathematics, Art, and the Politics of Value in Twentieth-Century United States by Clare Seungyoon Kim Bachelor of Arts Brown University, 2011 Submitted to the Program in Science, Technology and Society In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2019 © 2019 Clare Kim. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: Signatureredacted History, Anthr and Sc'nce, Technology and Society Signature redacted- August 23, 2019 Certified by: David Kaiser Germeshausen Professor of the History of the History of Science, STS Professor, Department of Physics Thesis Supervisor Certified by: Sianature redacted Christopher Capozzola MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OFTECHNOLOGY Professor of History C-) Thesis Committee Member OCT 032019 LIBRARIES 1 Signature redacted Certified by: Stefan Helmreich Elting E. Morison Professor of Anthropology Signature redacted Thesis Committee Member Accepted by: Tanalis Padilla Associate Professor, History Director of Graduate Studies, History, Anthropology, and STS Signature redacted Accepted by: Jennifer S. Light Professor of Science, Technology, and Society Professor of Urban Studies and Planning Department Head, Program in Science, Technology, & Society 2 The Subjects of Modernism Mathematics, Art, and the Politics of Value in Twentieth-Century United States By Clare Kim Submitted to the Program in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society on September 6, 2019 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society. -

Reading Guide for Morris Kline's Mathematics in Western Culture I

Reading Guide for Morris Kline's Mathematics in Western Culture I. Introduction 1. What aspects of mathematics are missing if we consider the subject as merely a series of techniques? 2. What is meant by \postulational thinking"? 3. What are some driving forces that motivate people to study mathematics? List 3 − 5 that come to mind. 4. In what ways is mathematics considered beautiful? 5. In mathematics, what does one mean by \truth"? 6. Comment on the use of mathematics to \control" or \have power" over nature. II. The Rule of Thumb in Mathematics 7. What is place value? List modern remnants of number bases other than base 10. 8. In reading Chapter II, consider the following groups of people and list contributions they made to mathematics: Egyptians Babylonians Greeks Hindus 9. What motivated each of the four groups above to contribute what it did to mathematics? 10. How do we show today that, as stated on page 23, \of all rectangles with a given area, the square has the least perimeter"? 11. In what ways has the mathematics of these people been involved with their religion? III. The Birth of the Mathematical Spirit 12. In what major ways did Greek mathematics differ from that of the Egyptians and Babylonians? 13. What is deductive reasoning? 14. Why did the Greeks prefer abstract concepts? 15. Note Plato's worldview. 16. Why did the Greeks study geometry? Compare this to the motivation for the Egyptians and Baby- lonians. 17. Note some examples of ways in which the Greeks expressed arithmetic ideas geometrically. -

The Bicentennial Tribute to American Mathematics 1776–1976

THE BICENTENNIAL TRIBUTE TO AMERICAN MATHEMATICS Donald J. Albers R. H. McDowell Menlo College Washington University Garrett Birkhof! S. H. Moolgavkar Harvard University Indiana University J. H. Ewing Shelba Jean Morman Indiana University University of Houston, Victoria Center Judith V. Grabiner California State College, C. V. Newsom Dominguez Hills Vice President, Radio Corporation of America (Retired) W. H. Gustafson Indiana University Mina S. Rees President Emeritus, Graduate School P. R. Haimos and University Center, CUNY Indiana University Fred S. Roberts R. W. Hamming Rutgers University Bell Telephone Laboratories R. A. Rosenbaum I. N. Herstein Wesleyan University University of Chicago S. K. Stein Peter J. Hilton University of California, Davis Battelle Memorial Institute and Case Western Reserve University Dirk J. Struik Massachusetts Institute of Technology Morris Kline (Retired) Brooklyn College (CUNY) and New York University Dalton Tarwater Texas Tech University R. D. Larsson Schenectady County Community College W. H. Wheeler Indiana University Peter D. Lax New York University, Courant Institute A. B. Willcox Executive Director, Mathematical Peter A. Lindstrom Association of America Genesee Community College W. P. Ziemer Indiana University The BICENTENNIAL TRIBUTE to AMERICAN MATHEMATICS 1776 1976 Dalton Tarwater, Editor Papers presented at the Fifty-ninth Annual Meeting of the Mathematical Association of America commemorating the nation's bicentennial Published and distributed by The Mathematical Association of America © 1977 by The Mathematical Association of America (Incorporated) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 77-14706 ISBN 0-88385-424-4 Printed in the United States of America Current printing (Last Digit): 10 987654321 PREFACE It was decided in 1973 that the Mathematical Association of America would commemorate the American Bicentennial at the San Antonio meet- ing of the Association in January, 1976, by stressing the history of Ameri- can mathematics. -

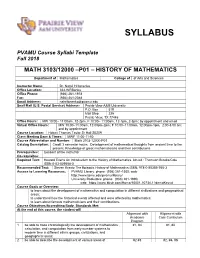

PVAMU Course Syllabi Template Fall 2018

SYLLABUS PVAMU Course Syllabi Template Fall 2018 MATH 3103/12000 –P01 – HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS Department of Mathematics College of of Arts and Sciences Instructor Name: Dr. Natali Hritonenko Office Location: 324-WRBanks Office Phone: (936)-261-1978 Fax: (936)-261-2088 Email Address: [email protected] Snail Mail (U.S. Postal Service) Address: Prairie View A&M University P.O. Box 519 Mail Stop 225 Prairie View, TX 77446 Office Hours: MW 10:00– 11:00am, 12-2pm, F 10:00– 11:00am, 12-1pm, 2-3pm; by appointment and email Virtual Office Hours: MW 10:00–11:00am, 12:00pm-2pm; F 10:00–11:00am, 12:00pm-1pm, 2:00-3:00 om; and by appointment Course Location: Hobart Thomas Taylor Sr Hall 2B209 Class Meeting Days & Times: MWF 11:00-11:50 Course Abbreviation and Number: Math 3103-12000-P01 Catalog Description: Credit 3 semester hours. Development of mathematical thoughts from ancient time to the present. Knowledge of great mathematicians and their contributions Prerequisites: Consent of the instructor Co-requisites: Required Text: Howard Evens An Introduction to the History of Mathematics. 6th ed.: Thomson Brooks/Cole ISBN 0-03-029558-0 Recommended Text: Steven Krantz The Episodic History of Mathematics ISBN: 978-0-88385-766-3 Access to Learning Resources: PVAMU Library: phone: (936) 261-1500; web: http://www.tamu.edu/pvamu/library/ University Bookstore: phone: (936) 261-1990; web: https://www.bkstr.com/Home/10001-10734-1?demoKey=d Course Goals or Overview: to learn about the development of mathematics and computation in different civilizations and geographical areas; to understand how the historical events affected and were affected by mathematics; to learn about famous mathematicians and their contributions. -

Schools of Greek Mathematical Practice: Geometry

Laura Winters Writing Sample SCHOOLS OF GREEK MATHEMATICAL PRACTICE: GEOMETRY The following writing sample is adapted from parts of the introduction, first chapter, and conclusion of my dissertation, in order to give an overall sense of the thesis and its scope. Pages 1-4 introduce the terminology and methods I use in my research; pages 5-11 give a brief analysis of the methodological and stylistic conventions that characterize the schools, with special attention to Euclid’s Elements; pages 11-20 survey the social and philosophical factors that contributed to the schools’ formations and that shaped the intellectual history of Greek geometry. INTRODUCTION Greek geometry, it is often claimed, was unlike any contemporary tradition of geometry: it neither followed the conventions of Babylonian mathematics nor used the methods of Egypt, despite the claims of Greeks themselves (including Herodotus) that the Egyptians were their first teachers in the art.1 Already, in its earliest extant texts Greek geometry appears as an advanced, highly systematic, theoretical study practiced by members of the philosophical schools. This has led many scholars to ascribe an almost mystical genius to the Greeks, and to see in the abstractness and complexity of their mathematics seeds of the modern habit of scientific inquiry.2 But by “Greek geometry” here scholars usually mean only geometry as Euclid did it. The particular conventions and standards of rigor practiced by Euclid have so thoroughly informed modern scholarship, that many still ascribe the characteristics of his work to Greek geometry in general. The textual legacy of Greek geometry, however, shows a diversity of methods, of which the style of Euclid is only a single strain. -

BOOK REVIEW Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modem Times, by Morris Kline. Oxford University Press, New York, 1972. Xvii

BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 80, Number 5, September 1974 BOOK REVIEW Mathematical thought from ancient to modem times, by Morris Kline. Oxford University Press, New York, 1972. xvii + 1238 pp. The history of mathematics is an enticing but neglected field. One reason for this situation lies in the nature of intellectual history. For any theoretical subject x, telling the story of x is not a conceptually distinct undertaking from describing the theory of x, though the two presentations often appear in different guises. The readership of a serious history of x will thus be largely limited to the few specialists in x, a small circulation at best. Worse yet, mathematics, or science for that matter, does not admit a history in the same sense as philosophy or literature do. An obsolete piece of mathematics is dead to all but the collector of relics. Discovering that the Babylonians knew harmonic analysis may be an astonishing feat of scholarship, but it is a supremely irrelevant piece of information to working scientists. Few of the serious historians of mathe matics have realized this; as a result, we are saddled today with competent histories of Greek and Renaissance mathematics, but we sadly lack such items of burning interest as "The Golden Days of Set Theory (1930-1965)" 'Topology in the Age of Lefschetz (1924-1953)", "The Beginnings of Probability (1932- • • •)", to cite but a few possible titles. Faced with these and many other problems, Morris Kline has chosen the courageous avenue of compromise. In his book, the Greeks get a 15% cut, the Egyptians are whisked on and offstage, the Arabs and Renaissance together make a fleeting 10% appearance, and the drama begins with René Descartes on Chapter 15 out of 51. -

Axiomatics Between Hilbert and the New Math: Diverging Views On

Axiomatics, Hilbert and New Math 1 Axiomatics Between Hilbert and the New Math: Diverging Views on Mathematical Research and Their Consequences on Education Leo Corry Tel-Aviv University Israel [email protected] Abstract David Hilbert is widely acknowledged as the father of the modern axiomatic approach in mathematics. The methodology and point of view put forward in his epoch-making Foundations of Geometry (1899) had lasting influences on research and education throughout the twentieth century. Nevertheless, his own conception of the role of axiomatic thinking in mathematics and in science in general was significantly different from the way in which it came to be understood and practiced by mathematicians of the following generations, including some who believed they were developing Hilbert’s original line of thought. The topologist Robert L. Moore was prominent among those who put at the center of their research an approach derived from Hilbert’s recently introduced axiomatic methodology. Moreover, he actively put forward a view according to which the axiomatic method would serve as a most useful teaching device in both graduate and undergraduate teaching mathematics and as a tool for identifying and developing creative mathematical talent. Some of the basic tenets of the Moore Method for teaching mathematics to prospective research mathematicians were adopted by the promoters of the New Math movement. Introduction The flow of ideas between current developments in advanced mathematical research, graduate and undergraduate student training, and high-school and primary teaching involves rather complex processes that are seldom accorded the kind of attention they deserve. A deeper historical understanding of such processes may prove rewarding to anyone involved in the development, promotion and evaluation of reforms in the teaching of mathematics. -

Carl B, Boyer--In Memoriam

HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 3 (1976), 387-394 CARLB, BOYER--INMEMORIAM BY MORRIS KLINE BROOKLYN COLLEGE OF THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK About one year ago several historians of mathematics made plans to dedicate the November 1976 issue of Historia Mathematics to Carl Boyer and to include a tribute to him. The occasion was to be Carl's seventieth birthday and his planned retirement. Carl's sudden death on April 26, 1976 has obliged us to convert a joyful task into a sorrowful one. No one who has had any contact at all with the history of mathematics needs to be introduced to the name of Carl Boyer or his writings. But few may know the full extent of Carl's contri- butions. These were not only extensive and deep but unique, and to appreciate them we must look back somewhat. Mathematical research on this continent began to show some- what widespread activity about 1900. (Of course there were a few notable earlier workers, among them the Europeans whom Johns Hopkins imported to start its graduate training and research program). This research, which took the direction of seeking new results, expanded in each successive decade. But the history of mathematics languished. It is true that initially the American Mathematical Society (founded as the New York Mathematical Society in 1888) announced its intent to pay attention to history and teaching as well as to new creations, and the early issues of the Bulletin of that Society did contain some fine historical articles. But the Society soon abandoned this program and narrower its concerns to promoting and publishing research for new results. -

A-History-Of-Mathematics-3Rded.Pdf

A History of Mathematics THIRD EDITION Uta C. Merzbach and Carl B. Boyer John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Copyright r 1968, 1989, 1991, 2011 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans mitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Pub lisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750 8400, fax (978) 646 8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748 6011, fax (201) 748 6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or war ranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a par ticular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suit able for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. -

Peter Hilton Doctor Honoris Causa

PETER HILTON DOCTOR HONORIS CAUSA Uni\mitat ..\ ulooomad e Barce lona UN IVERSITAT AUTÓNOM A DE BARCELÜI'\¡\ DOcrOR HONORIS CAUSA PETER HILTON DlSCL'RS LLEGIT A LA CERL\10NIA D'IN VESTIDURA CELEBRA DA A LA SALA D'A C7rES D'AQUEST RECTORA T EL D1A 16 DE MA1G DE L'AN Y 1989 BELLATERRA, 1989 EDrTATPEL SERVEI DE PUBLlCAClONS DE LA UNIVERsrT AT ALTOKOMA DE BARCELONA 08193 Bellatcrra (Barcelona) IMPRÉS PER GRÁ FICAS UN IÓ)J Tcrrassa (Barcelona) Dipbsil Legal: 8.-21,424- 1989 Printed in Spain PRESENTAcró DE PETER HILTON PER MANUEL CASTELLET 1 SOLANAS Excel.lentíssim i Magnífic Senyor Rector, Digníssimes Autoritats, Estimats Col.legues, Senyores i Senyors: Quan a I'octubre de 1964 el Dr. Josep Teixidor ens recomanava com a llibre de text per a l'assignatura de Topologia de 5e curs el manual Homology Theory de P. Hilton i S. Wylie, poc em podia imaginar aleshores que avui, gairebé vint-i-cinc anys després, em trobaria a la Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, presentan! davant el seu Col.legi de Doctors, precisament Peter Hilton. No m'ho podia im aginar per diverses raons, alguna de tan trivial com que l'Autonoma no existía ni en el món de les idees; pero fonamentalment perque en aquells moments jo no sabia que era la topologia algebraica ni sabia qui era Peter Hilton. La meya coneixen\,a amb Hilton ha seguit un procés d'aproximacions succesives, comen\,ant per un llibre, passant per articles de recerca i concloent en un coneixement personal i en una amistat que m'honora que ens ha portat la col.laboració científica. -

Mathematics As a Humanistic Discipline Elena Anne Marchisotto California State University, Northridge

Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal Issue 7 Article 9 4-1-1992 Mathematics as a Humanistic Discipline Elena Anne Marchisotto California State University, Northridge Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/hmnj Part of the Logic and Foundations of Mathematics Commons, and the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Marchisotto, Elena Anne (1992) "Mathematics as a Humanistic Discipline," Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal: Iss. 7, Article 9. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/hmnj/vol1/iss7/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MATHEMATICS AS A HUMANISTIC DISCIPLINE ElenaAnne Marchisotto ProfessorofMQ1hem1ltics California State University J8Il NordhoffStreet. Nonhridge It is said that the mono which adorned the A conference was held at Williams College in doors of Plato's Academy advised. "Let no one Williamstown. Maryland, in 1982, to evaluate the unversed in mathematics enter here." For the mathematical needs of students in other disciplines Greeks, the study of mathematics furnished the and the implementation of curricula to meet those finest training field for the mind. It occupied an needs. Papers were presented by mathematicians and esteemed place in the curriculum of Plato's mathematics educators identifying requirements for Academy. No person was considerededucated if specific field s: Isaac Greber for Engineering, William he did not know mathematics. ScherlisandMary ShawforComputerScience.Stanley Zionts for Business, Jack Lockhead for the Physical Mathematics hasnotretainedsuch adominant Sciences, and Robert Norman the Social Sciences.