COMMUNITY FOOD SECURITY RESEARCH REPORT a Participatory Action Research Project in Partnership with Activating Change Together for Community Food Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

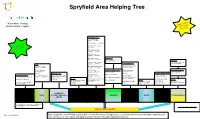

Spryfield Area Helping Tree

Spryfield Area Helping Tree lan Recreation Therapy e a p Mak w follo Mental Health Program and ugh! thro Spiritual Resources #9 Calvary United Baptist…..477-4099 #10 City Church …..479-2489 nd it! A #11 Emmanuel Anglican….. et F 477-1783 G Fun! ave H #12 Saint Augustine’s Anglican….. 477-5424 #13 Saint James Anglican…..477-2979 #14 Saint Joseph’s Indoor Pool Monastery…..477-3937 #20 Spryfield Lion’s Wave Pool…..477-POOL Gardening #15 Saint John The Baptist #32 Urban Farm Museum Catholic …...477-3110 Community Centres Society of Spryfield Yoga #25 Captain William Spry #4 Ready to Rumba #16 Saint Michael’s Roman Community Centre/wave Dance…..444-3129 Catholic …...477-3530 pool…..477-POOL #5 Chocolate Lake #17 Saint Paul’s Supervised Beaches (Free) #26 Chocolate Lake Halifax Public Libraries Recreation Centre….. United …...477-3937 #21 Kidston Lake Community Center…… #33 Captain William 490-4607 490-4607 Spry…..490-5818 Wellness Centre Senior’s Club and Centres #7 Chebucto Connections #18 Saint Phillips #22 Long Pond Beach #30 Spryfield Senior Free Walking Groups #6 Captain William Spry #27 Harrietsfield/ and Chebucto Community Anglican…..477-2979 Centre…..477-5658 #1 Heart and Stroke Walkabout Centre …..477-7665 Williamswood Community Wellness Centre ….. #23 Crystal Crescent Beach Skating #19 Salvation Army Spryfield Centre…...446-4847 #31 Golden Age Social #2 Chebucto Hiking Club 487-0690 Bowling #8 Spryfield Lions Rink and Community Church….. #24 Cunard Beach Dance Centre Society Recreation Centre….. 477-5393 #28 Spryfield Recreation #34 Spryfield #3 Visit one of the many trails #29 Ready to Rumba Young at Heart 477-5456 Centre Bowlarama…..479-2695 available in HRM Dance….444-3129 Club…..477- 3833 COMMUNITY FREE WALKING SPIRITUAL COMMUNITY SENIOR’S YOGA SUPPORT/ WELLNESS SKATING SWIMMING DANCE MISCELLANEOUS GROUPS RESOURCES CENTRES CENTRES GROUPS The Spryfield Area Helping Tree was adapted from the PEI Helping Tree. -

TABLE of CONTENTS 1.0 Background

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Background ....................................................................... 1 1.1 The Study ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 The Study Process .............................................................................................. 2 1.2 Background ......................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Early Settlement ................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Community Involvement and Associations ...................................................... 4 1.5 Area Demographics ............................................................................................ 6 Population ................................................................................................................................... 6 Cohort Model .............................................................................................................................. 6 Population by Generation ........................................................................................................... 7 Income Characteristics ................................................................................................................ 7 Family Size and Structure ........................................................................................................... 8 Household Characteristics by Condition and Period of -

Case 20102: Amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy for Halifax and the Land Use By-Law for Halifax Mainland for 383 Herring Cove Road, Halifax

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 11.2.1 Halifax Regional Council October 30, 2018 November 27, 2018 TO: Mayor Savage Members of Halifax Regional Council Original Signed SUBMITTED BY: For Councillor Stephen D. Adams, Chair, Halifax and West Community Council DATE: October 10, 2018 SUBJECT: Case 20102: Amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy for Halifax and the Land Use By-law for Halifax Mainland for 383 Herring Cove Road, Halifax ORIGIN October 9, 2018 meeting of Halifax and West Community Council, Item 13.1.7. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY HRM Charter, Part 1, Clause 25(c) – “The powers and duties of a Community Council include recommending to the Council appropriate by-laws, regulations, controls and development standards for the community.” RECOMMENDATION That Halifax Regional Council Council give First Reading to consider the proposed amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy (MPS) for Halifax and Land Use By-law for Halifax Mainland (LUB) as set out in Attachments A and B of the staff report dated September 11, 2018, to create a new zone which permits a 7-storey mixed-use building at 383 Herring Cove Road, Halifax, and schedule a public hearing. Case 20102 Council Report - 2 - October 30, 2018 BACKGROUND At their October 9, 2018 meeting, Halifax and West Community Council considered the staff report dated September 11, 2018 regarding Case 20102: Amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategy for Halifax and the Land Use By-law for Halifax Mainland for 383 Herring Cove Road, Halifax For further information, please refer to the attached staff report dated September 11, 2018. -

Dartmouth, Highlights Key Themes in Your Area and Across the Province, and Outlines What DNS Is Doing to Help

Doctors Nova Scotia’s Community Listening Tour Physicians in Nova Scotia are under pressure. Faced with large patient rosters and limited resources, they are worried about their patients, their practices and their personal lives. That’s why this spring, members of Doctors Nova Scotia’s (DNS) senior leadership team embarked on a province-wide listening tour. They attended 29 meetings with a total of 235 physicians in 24 communities – learning about the challenges of practising medicine in Nova Scotia from people who are experiencing them first-hand. Doctors Nova Scotia held 11 meetings in your zone. This report summarizes the discussion DNS staff members had with physicians in Dartmouth, highlights key themes in your area and across the province, and outlines what DNS is doing to help. Community Report: Dartmouth Meetings in Zone 4 – Central Location Date # of physicians Cobequid Community Health Centre May 18 16 Twin Oaks Memorial Hospital June 7 3 Musquodoboit Valley Memorial Hospital June 7 2 Eastern Shore Memorial Hospital June 7 3 QEII – Veteran’s Memorial Building June 13 4 Dartmouth – NSCC Waterfront Campus June 14 8 Spryfield Medical Centre June 14 7 St. Margaret’s Community Centre June 21 13 Dalhousie – Collaborative Health Education Building June 21 4 IWK June 22 2 Gladstone Family Practice Associates Sept 10 15 Individual correspondence Aug-Sep 5 TOTALS 11 meetings 82 physicians Issues in Dartmouth The association held one session in Dartmouth at the NSCC Waterfront Campus, but attendance was low. This is in part attributable to physicians leading very busy lives, but it may also be a reflection of the lack of connection and community among physicians in Halifax or a lack of confidence in DNS’s ability to influence change. -

Spryfield Chooses Halifax ANC

community stories October 2005 ISBN #1-55382-146-7 Spryfield Chooses Halifax ANC Organizational change The Action for Neighbourhood Change project (ANC) may be complex but its With a population of 359,111, the amal- purpose is clear. The initiative is about real gamated Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM) people helping one another to make their makes up about 40 percent of Nova Scotia’s neighbourhoods better places to live. Since population and 15 percent of the population the project began in February 2005, it has of the Atlantic provinces [Statistics Canada 2001]. generated optimism and hope among Unfortunately, with amalgamation came decreased community members. The partners are autonomy at the neighbourhood level for the excited that the program is having the financing and operation of local initiatives. This desired results: Citizens are becoming shift is not in accord with recent developments at involved in changing their neighbourhoods the United Way of Halifax Region (UWHR). and government is hearing the feedback it needs to support them effectively. This Since 1998, UWHR has undergone a sig- series of stories presents each of the five nificant change in direction, moving from addres- ANC neighbourhoods as they existed at sing community needs to building community the start of the initiative. A second series strengths. Its ecological approach emphasizes will be published at the end of the ANC’s the roles and importance of the individual, the 14-month run to document the changes family, the neighbourhood and the larger com- and learnings that have resulted from the munity – institutions, associations and agencies. effort. For more information about ANC, Where these four entities overlap is where UWHR visit: www.anccommunity.ca believes community building can occur – and is the new locus of United Way support. -

Assessing Agricultural Suitability in Spryfield, NS

ASSESSING COMMUNITY AGRICULTURAL SUITABI LITY IN SPRYFIELD, NOVA SCOT IA PREPARED BY: JARED D ALZIEL MARCH 5, 2012 DALHOUSIE UNVERSITY & CHEBUCTO CONNECTIO NS PROJECT SUPERVISOR: MARJORIE WILLISON D a l z i e l | 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Context ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Constraints Analysis ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Restrictive Land Uses ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Soil Type ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Land Slope ............................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Sun Exposure ........................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Runoff Prevention ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Neighbourhood Change in Halifax Regional Municipality, 1970 to 2010: Applying the “Three Cities” Model

Neighbourhood Change in Halifax Regional Municipality, 1970 to 2010: Applying the “Three Cities” Model Victoria Prouse, Jill L Grant, Martha Radice, Howard Ramos, Paul Shakotko With assistance from Malcolm Shookner, Kasia Tota, Siobhan Witherbee January 2014 Neighbourhood Change in Halifax Regional Municipality, 2 Neighbourhood Change in Halifax Regional Municipality, 1970 to 2010: Applying the “Three Cities” Model Victoria Prouse, Jill L Grant, Martha Radice, Howard Ramos, Paul Shakotko With assistance from Malcolm Shookner, Kasia Tota, Siobhan Witherbee [Three Cities data provided by J David Hulchanski and Richard Maraanen] The Neighbourhood Change Research Partnership is funded through a Partnership Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The Halifax team has received valued contributions from community partners: United Way Halifax, Halifax Regional Municipality, and the Province of Nova Scotia (Community Counts). Visit the national project’s web site: http://neighbourhoodchange.ca/ Visit the Halifax project web site: http://theoryandpractice.planning.dal.ca/neighbourhood/index.html Neighbourhood Change in Halifax Regional Municipality, 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Neighbourhood Change Research Partnership significant disparities in average individual income (NCRP) is conducting a national study comparing levels. Inequality is a relative condition, ranging trends in individual incomes for a 30 to 40 year from a limited difference in available resources to a period in several Canadian cities. We seek to considerable gap. Social polarization – a “vanishing identify and interpret trends in income to determine middle class” (MacLachlan and Sawada, 1997, 384) whether socio-spatial polarization—a gap between – implies a pattern of increasing income inequality rich and poor expressed in the geography of the which results in growing numbers of census tracts city—has been increasing. -

Community Health Teams Free Health and Wellness Programs

Community Health Teams FREE HEALTH & WELLNESS PROGRAMS Photo courtesy of John Archambault How to Register: • 902-460-4560 • Drop in September 2016 - February 2017 • www.communityhealthteams.ca To Registercall 902-460-4560 Register now Like us on Facebook facebook.com/communityhealthteams Visit us online CommunityHealthTeams.ca WHAT IS A COMMUNITY HEALTH TEAM? A Community Health Team offers free wellness programs and services in your community. The range of programs and services offered by each Community Health Team are shaped by what we have heard citizens need to best support their health. Your local Community Health Team: • Offers free group wellness programs at different times and community locations to make it easier for you to access sessions close to home. • Offers free wellness navigation to help you prioritize health goals and connect to the resources that you need. • Works closely together with community organizations toward building a stronger and healthier community. Meet friendly people and get healthier together at your local Community Health Team. Bedford / Sackville Dartmouth Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 833 Sackville Drive (upper level), Lower Sackville 58 Tacoma Drive, Dartmouth Serving the communities of Beaver Bank, Fall River, Serving the communities of Dartmouth, Cole Hammonds Plains, Sackville, and Waverley. Harbour, Eastern Passage, Lawrencetown, Mineville, North and East Preston. Chebucto (Halifax Mainland) Halifax Peninsula Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 16 Dentith Road, Halifax Suite 105 6080 Young Street, Halifax Serving the communities of Spryfield, Fairview, Serving the communities of downtown, north end, Clayton Park, Herring Cove, Armdale, Sambro Loop, south end, and west end Halifax. -

Community Health Teams Provides Space Free of Charge to Community Groups to Offer Their Programs and Services for the Public

Item No. 11.3.1 Community Health FREE Teams HEALTH & Winter 2016 WELLNESS January - April Registration begins PROGRAMS Tuesday, January 12 at 8:30 a.m. HowTo Registercall to Register: 902-460-4560 • 902-460-4560 • Drop in • www.communityhealthteams.ca Like us on Facebook facebook.com/communityhealthteams Visit us online CommunityHealthTeams.ca WHAT IS A COMMUNITY HEALTH TEAM? A Community Health Team offers free wellness programs and services in your community. The range of programs and services offered by each Community Health Team are shaped by what we have heard citizens needed to best support their health. Your local Community Health Team: • Offers free group wellness programs at different times and community locations to make it easier for you to access sessions close to home. • Offers free wellness navigation to help you prioritize health goals and connect to the resources that you need. • Works closely together with community organizations toward building a stronger and healthier community. Meet friendly people and get healthier together at your Community Health Team! Bedford/Sackville Dartmouth Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 833 Sackville Drive (upper level), Lower Sackville 58 Tacoma Drive, Dartmouth Serving the Communities of Beaver Bank, Fall River, Serving the Communities of Dartmouth, Cole Hammonds Plains, Sackville, and Waverley. Harbour, Eastern Passage, Lawrencetown, Mineville, North and East Preston. Chebucto Halifax Peninsula Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 16 Dentith Road, Halifax Suite 105 6080 Young Street, Halifax Serving the Communities of Spryfield, Fairview, Serving the Communities of Downtown, North End, Clayton Park, Herring Cove, Armdale, Sambro Loop, South End, and West End Halifax. -

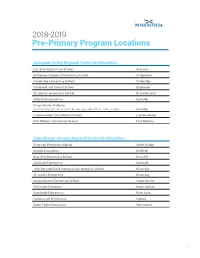

Pre-Primary Program Locations

2018-2019 Pre-Primary Program Locations Annapolis Valley Regional Centre for Education L.E. Shaw Elementary School Avonport Bridgetown Regional Community School Bridgetown Cambridge Elementary School Cambridge Coldbrook and District School Coldbrook Champlain Elementary School Granville Ferry Aldershot Elementary Kentville Kings County Academy (Partnership with licensed child care operator off site from school) Kentville Lawrencetown Consolidated School Lawrencetown Port Williams Elementary School Port Williams Cape Breton-Victoria Regional Centre for Education Riverside Elementary School Albert Bridge Baddeck Academy Baddeck Bras d’Or Elementary School Bras d’Or Coxheath Elementary Coxheath John Bernard Croak Victoria Cross Memorial School Glace Bay St. Anne’s Elementary Glace Bay Mountainview Elementary School Howie Centre Ferrisview Elemetary North Sydney Greenfield Elementary River Ryan Harbourside Elementary Sydney Robin Foote Elementary Westmount 1 Chignecto-Central Regional Centre for Education Brookfield Elementary School Brookfield Chiganois Elementary School Debert Debert Elementary School Debert Kennetcook District Elementary School Kennetcook Northport Consolidated Elementary School (Pre-primary Program will be offered at Cyrus Eaton Elementary School) Northport Cobequid Consolidated Elementary School Old Barns Oxford Regional Education Centre (Pre-primary Program will be offered in the community, at a location to be determined) Oxford Cyrus Eaton Elementary School Pugwash River Hebert District School River Hebert Winding River -

Community Health Teams

Community Health Teams FREE HEALTH & WELLNESS PROGRAMS 902-460-4560 How to Register: • 902-460-4560 September 2017- • Drop in • www.communityhealthteams.ca February 2018 VisitTo usRegistercall online 902-460-4560 CommunityHealthTeams.ca Register now facebook.com/communityhealthteams @CHTs_NSHA WHAT IS A COMMUNITY HEALTH TEAM? A Community Health Team offers free wellness programs and services in your community. The range of programs and services offered by each Community Health Team are shaped by what we have heard citizens need to best support their health. Your local Community Health Team: • Offers free group wellness programs at different times and community locations to make it easier for you to access sessions close to home. • Offers free wellness navigation to help you prioritize health goals and connect to the resources that you need. • Works closely together with community organizations toward building a stronger and healthier community. Meet friendly people and get healthier together at your local Community Health Team Bedford / Sackville Chebucto (Halifax Mainland) Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 833 Sackville Drive (upper level), Lower Sackville 16 Dentith Road, Halifax Until December 5, 2017 Serving the communities of Spryfield, Fairview, Clayton Park, Bedfiord Place Mall, 1658 Bedford Highway, Herring Cove, Armdale, Sambro Loop, the Pennants, Purcell’s Bedford - Effective December 8, 2017 Cove, Tantallon, Hubbards, St.Margaret’s Bay, Beechville, Serving the communities of Beaver Bank, Bedford, Fall River, Lakeside, Timberlea, Prospect, Hatchet Lake, and Hubley. Hammonds Plains, Sackville, and Waverley. Dartmouth Halifax Peninsula Community Health Team (CHT) Community Health Team (CHT) 58 Tacoma Drive, Dartmouth Suite 105 6080 Young Street, Halifax Serving the communities of Dartmouth, Cole Harbour, Eastern Serving the communities of downtown, north end, south end, Passage, Lawrencetown, Mineville, North and East Preston. -

Order M07245 Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board In

ORDER M07245 NOVA SCOTIA UTILITY AND REVIEW BOARD IN THE MATTER OF THE EDUCATION ACT - and - IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION by the HALIFAX REGIONAL SCHOOL BOARD to amend the boundaries of the electoral districts BEFORE: Roland A. Deveau, Q.C., Vice-Chair ORDER An Application having been made by the Halifax Regional School Board pursuant to s. 43 of the Education Act and the Board having issued its decision on April 28, 2016; IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that the application is approved as follows: 1. The number of electoral districts for the Halifax Regional School Board is confirmed at 8, each electing one member; 2. The proposed boundaries of the electoral districts are approved; and 3. The descriptions of all electoral districts are set out in Schedule "A", attached to and forming part of this Order; AND IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that all provisions of the Education Act and the Municipal Elections Act and any other acts of the Province of Nova Scotia applying to the preparation for and holding of the regular election of school board members in the year 2016 will be complied with as if the above-noted changes had been made on the first day of March 2016, but for all other purposes such changes shall take effect on the first day of the first meeting of the School Board after the election of school board members for the year 2016. DATED at Halifax, Nova Scotia this 28th day of April, 2016. Clerk of the Board Document: 245776 Schedule “A” Electoral District 1 Eastern Shore/Fall River (HRM Districts 1 and 2 - Waverley - Fall River - Musquodoboit Valley and Preston - Porters Lake - Eastern Shore).