Aalborg Universitet Destination Development in Western Siberia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nǐ Hǎo Altay!

Nǐ hǎo Altay! Duration: 13 days / 12 nights Route: Novosibirsk — The Ob sea (sanatorium park) — Barnaul — Polkovnikovo — Biysk — Srostki — Manzherok — Chemal — The Teletskoye lake — The Karakol valley — Chibit — The Manzherok lake — The Sky blue Katun — The Altai village — The Belokurikha resort — Novosibirsk, 2850 km. The number of people in the group — from 6 to 40 people. Time start of the tour: any Meeting at the airport Tolmachevo (Novosibirsk city). Transfer Tolmachevo — the Ob Sea (stop Day 1 for a tea break in the park hotel, photostop) — Gran Altai (Russian buffet) — Barnaul city (260 km). Hotel accommodation. Dinner. Tour around the city of Barnaul starting on the Demidov square through historical streets towards the sightseeng platform in the Nagorny Park. letters send during the war and the military photographs. Transfer Polkovnikovo — Biysk (100 km) — Day 2 a city built by the decree of the emperor of Russia Peter the Great in the 18th century. Biysk now has the status of the City of Breakfast. Transfer Barnaul city — Polkovnikovo village (70 science and it is the main gateway to the km) — the birthplace of cosmonaut No. 2 Herman Titov. Altai Mountains. Excursion «Old streets of Excursion to the Museum of Cosmonautics. G.S. Titov. All Biysk» starting at the monument of Peter exhibits of the museum are thematically divided and placed the Great going to the main guns, visit to the in four halls: «The Morning of the Space Age» — introduces Chujsky museum. Lunch. Transfer Biysk — the first steps of man into space, «Altai and space» — Srostki village (50 km) — the birthplace of this story tells how a man began to live in space, «School the famous actor, writer, film director Vasily years of Herman Titov» — you can see what textbooks the Shukshin. -

Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty Aggregate Memorandum Of

Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty Aggregate Memorandum of Understanding Exchange (As of July 1, 2009) Excerpts only: Russia and the United States Available at the Federation of American Scientists Russian Federation MOU Data Effective Date - 1 Jul 2009: 1 `` SUBJECT: NOTIFICATION OF UPDATED DATA IN THE MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING, AFTER THE EXPIRATION OF EACH SIX-MONTH PERIOD NOTE: FOR THE PURPOSES OF THIS MEMORANDUM, THE WORD "DASH" IS USED TO DENOTE THAT THE ENTRY IS NOT APPLICABLE IN SUCH CASE. THE WORD "BLANK" IS USED TO DENOTE THAT THIS DATA DOES NOT CURRENTLY EXIST, BUT WILL BE PROVIDED WHEN AVAILABLE. I. NUMBERS OF WARHEADS AND THROW-WEIGHT VALUES ATTRIBUTED TO DEPLOYED ICBMS AND DEPLOYED SLBMS, AND NUMBERS OF WARHEADS ATTRIBUTED TO DEPLOYED HEAVY BOMBERS: 1. THE FOLLOWING ARE NUMBERS OF WARHEADS AND THROW-WEIGHT VALUES ATTRIBUTED TO DEPLOYED ICBMS AND DEPLOYED SLBMS OF EACH TYPE EXISTING AS OF THE DATE OF SIGNATURE OF THE TREATY OR SUBSEQUENTLY DEPLOYED. IN THIS CONNECTION, IN CASE OF A CHANGE IN THE INITIAL VALUE OF THROW-WEIGHT OR THE NUMBER OF WARHEADS, RESPECTIVELY, DATA SHALL BE INCLUDED IN THE "CHANGED VALUE" COLUMN: THROW-WEIGHT (KG) NUMBER OF WARHEADS INITIAL CHANGED INITIAL CHANGED VALUE VALUE VALUE VALUE (i) INTERCONTINENTAL BALLISTIC MISSILES SS-11 1200 1 SS-13 600 1 SS-25 1000 1200 1 SS-17 2550 4 SS-19 4350 6 SS-18 8800 10 SS-24 4050 10 (ii) SUBMARINE-LAUNCHED BALLISTIC MISSILES SS-N-6 650 1 SS-N-8 1100 1 SS-N-17 450 1 SS-N-18 1650 3 SS-N-20 2550 10 SS-N-23 2800 4 RSM-56 1150*) 6 *) DATA WILL BE CONFIRMED BY FLIGHT TEST RESULTS. -

The Concept of Infamy in Roman

ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND SUSTAINABILITY ISSUES ISSN 2345-0282 (online) http://jssidoi.org/jesi/ 2020 Volume 7 Number 3 (March) http://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.7.3(50) Publisher http://jssidoi.org/esc/home HEALTH TOURISM IN LOW MOUNTAINS: A CASE STUDY 3 4 Alexandr N. Dunets ¹*, Veronika V. Yankovskaya ², Alla B. Plisova , Mariya V. Mikhailova , 5 6 Igor B. Vakhrushev , Roman A. Aleshko 1Altai State University, Lenin Ave., 61, 656049, Barnaul, Russian Federation 2Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, Stremyanny lane, 36, 117997, Moscow, Russian Federation 3Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Leningradsky Prospekt, 49, 125993, Moscow, Russian Federation 4 Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Trubetskaya st., 8-2, 119991, Moscow, Russian Federation 5V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University, Prospekt Vernadskogo 4, Simferopol, 295007, Russian Federation 6Northern (Arctic) Federal University, Severnaya Dvina Emb. 17, 163002, Arkhangelsk, Russian Federation E-mails:1* [email protected]; Received 14 August 2019; accepted 20 December 2019; published 30 March 2020 Abstract. Health tourism is a specific type of tourism with great prospects. Most people do not have time for long trips, but there is a great need for a change of scenery and restoration of strength. There are many examples when in the regions in order to improve health and relaxation, nearby areas are being developed. It is most promising to create programs for such tourism near existing resorts that have the necessary infrastructure and medical facilities, while individual client requests must be taken into account. It is proposed to research health tourism as a territorial tourist complex, which includes not only specialized infrastructure but also territories adjacent to resorts. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

On State Register of Microfinance Organisations | Bank of Russia

12 Neglinnaya Street, Moscow, 107016 Russia 8 800 300-30-00 www.cbr.ru News On state register of microfinance organisations 30 June 2015 Press release On 26 June 2015, the Bank of Russia took decisions: to include information on the following entities in the state register of microfinance organisations: NATIONAL FINANCIAL GROUP, limited liability company (the city of Moscow), CENTRE-SERVICE-GROUP, limited liability company (the city of Moscow), UNICOM FINANCE, limited liability company (the city of Moscow), OUR TRADITIONS, limited liability company (the city of Moscow), FINANCE-POSTAVKA, limited liability company (the city of Moscow), FINHELP, limited liability company (the city of Moscow), EFES Financial Company, limited liability company (the city of Nizhny Novgorod), DobroZaim Bystroe Reshenie, limited liability company (the city of Moscow), APOLLO, limited liability company (the city of Barnaul, Altai Territory), Golden Elephant, limited liability company (the city of Togliatti, Samara Region), Region Dengi, limited liability company (the city of Gatchina, Gatchina District, Leningrad Region), Dingo Dengi, limited liability company (the city of Obninsk, Kaluga Region), Euro, limited liability company (the village of Musirmy, Urmarsky District, Republic of Chuvashia) Fund for Support of Small Entrepreneurship of the Petvovsk-Transbaikal District (the city of Petrovsk- Transbaikalsky, Trans-Baikal Territory), Siberian Financial Union, limited liability company (the city of Yugra, Kemerovo Region), Avtomatizatsia Schetov, limited liability -

BR IFIC N° 2611 Index/Indice

BR IFIC N° 2611 Index/Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Part 1 / Partie 1 / Parte 1 Date/Fecha 22.01.2008 Description of Columns Description des colonnes Descripción de columnas No. Sequential number Numéro séquenciel Número sequencial BR Id. BR identification number Numéro d'identification du BR Número de identificación de la BR Adm Notifying Administration Administration notificatrice Administración notificante 1A [MHz] Assigned frequency [MHz] Fréquence assignée [MHz] Frecuencia asignada [MHz] Name of the location of Nom de l'emplacement de Nombre del emplazamiento de 4A/5A transmitting / receiving station la station d'émission / réception estación transmisora / receptora 4B/5B Geographical area Zone géographique Zona geográfica 4C/5C Geographical coordinates Coordonnées géographiques Coordenadas geográficas 6A Class of station Classe de station Clase de estación Purpose of the notification: Objet de la notification: Propósito de la notificación: Intent ADD-addition MOD-modify ADD-ajouter MOD-modifier ADD-añadir MOD-modificar SUP-suppress W/D-withdraw SUP-supprimer W/D-retirer SUP-suprimir W/D-retirar No. BR Id Adm 1A [MHz] 4A/5A 4B/5B 4C/5C 6A Part Intent 1 107125602 BLR 405.6125 BESHENKOVICHI BLR 29E28'13'' 55N02'57'' FB 1 ADD 2 107125603 -

Altai Peaks and Rivers

ALTAI PEAKS AND RIVERS Welcome to the majestic Altai Republic, land of mountains, nomads and heart-stopping adventures. From remote villages TOUR DURATION to superb ski resorts to pristine caves and mountain lakes, this 13 days / 12 nights tour gives you a complete picture of Altai’s extraordinary GROUP SIZE diversity. 6 -12 people The Altai Republic spans a vast 92,500sqm at the junction of the Siberian taiga, the steppes of Kazakhstan and the semi-deserts of Mongolia. A quarter REGIONS VISITED Novosibirsk, Altai region of the Altai Republic is covered in forest, and the region is rich in rivers and lakes, with more than 20,000 tributaries winding their way through the mountains on their northward journey to the Arctic Ocean. The nearest large START CITY — END CITY Novosibirsk — Novosibirsk city is Novosibirsk, an important junction of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Novosibirsk is about 350km from the Altai border, which in Siberian terms, is not particularly far away! This city, the third largest in Russia, is where our SEASON Winter, December — April adventure begins. This tour takes place in late winter, the perfect time for enjoying skiing and TOUR CATEGORY Combination tour snowboarding on Altai’s pristine slopes. You’ll also get to experience adventurous winter activities like dog sledding and snowmobiling in eerily beautiful taiga forests and snow sprinkled meadows. Novosibirsk is a great PRICE jumping off point, with its superb restaurants and stately architecture. Our From US $3950* journey is a cultural discovery as well, as we experience both urban and rural Russian life, and the unique traditions of the indigenous Altay people. -

WCER Special Economic Zones

Consortium for Economic Policy Research and Advice WCER Canadian Association Institute Working Academy International of Universities for the Economy Center of National Development and Colleges in Transition for Economic Economy Agency of Canada Reform Special Economic Zones Moscow IET 2007 UDC 332.122 BBC 65.046.11 S78 Special Economic Zones / Consortium for Economic Policy Research and Advice – Moscow : IET, 2007. – 247 p. : il. – ISBN 9785932552070 Agency CIP RSL Authors: Prihodko S., Volovik N., Hecht A., Sharpe B., Mandres M. Translated from the Russian by Todorov L. Page setting: Yudichev V. The work is concerned with free economic zones classification and basic principles of operation. Foreign experience of free economic zones creation is regarded. Considerable attention is paid to the his tory of free economic zones organization in Russia. The main causes of failures of their implementation are analyzed. At present the work on creation of special economic zones of main types – industrial and production, innovation and technological, tourist and recreation has started in Russia. The main part of the work is devoted to Canadian experience of regional development. JEL Classification: R0, R1. The research and the publication were undertaken in the framework of CEPRA (Consortium for Economic Policy Re search and Advice) project funded by the Canadian Agency for International Development (CIDA). UDC 332.122 BBC 65.046.11 ISBN 9785932552070 5, Gazetny per., Moscow, 125993 Russia Tel. (495) 6296736, Fax (495) 2038816 [email protected], http://www.iet.ru Table of Contents I. Regional Development in Canada..........................................7 1. An Introduction to Regional Development in Canada................7 2. -

Reasons for the Ways of Using Oilcakes in Food Industry

ISSN 2308-4057. Foods and Raw Materials, 2016, vol. 4, no. 1 FOOD PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY REASONS FOR THE WAYS OF USING OILCAKES IN FOOD INDUSTRY M. S. Bochkareva, E. Yu. Egorovab, I. Yu. Reznichenkoc,*, and V. M. Poznyakovskiyd a Biysk Institute of Technology (branch), Polzunov Altai State Technical University, Trofimova Str. 27, Biysk, 659305 Russian Federation b Polzunov Altai State Technical University, Lenin Str. 46, Barnaul, 656038 Russian Federation c Kemerovo Institute of Food Science and Technology (University), Stroiteley blvd. 47, Kemerovo, 650056 Russian Federation d Sochi State University, Sovetskaya Str. 26а, Sochi, 354000 Russian Federation * e-mail: [email protected] Received April 28, 2015; Accepted in revised form December 18, 2015; Published June 27, 2016 Abstract: Using of secondary raw material resources from the oil and fat industry enterprises for new foodstuff development is an important task giving the chance of products range expansion, which are enriched in many indispensable components. The compliance with quality analysis of oilcakes from several types of olive raw materials, traditional and non-traditional for Russia, to fundamental technical requirements of the normative documents of the Russian Federation, determination of the list of quality and safety indicators of the oilcakes and reasons for the ways of processing them into food became the research purposes. Objects of researches were the oilcakes received in the conditions of specialized enterprises of Altai Krai from the appropriate types of olive raw materials. They are oilcakes made from: Siberian cedar pine kernels, walnut kernels, seeds of Cucurbita pepo, sesame seeds, black cumin seeds, flax seeds, milk thistle seeds, amaranth seeds. -

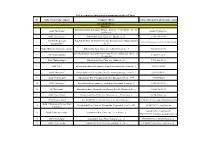

List of Exporters Interested in Supplying Grain to China

List of exporters interested in supplying grain to China № Name of exporting company Company address Contact Infromation (phone num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed Zabaykalsky Krai, Kalgansky District, Bura 1st , Vitaly Kozlov str., 25 1 OOO ''Burinskoe'' [email protected]. building A 2 OOO ''Zelenyi List'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Butina str., 93 8-914-469-64-44 AO "Breeding factory Zabaikalskiy Krai, Chernyshevskiy area, Komsomolskoe village, Oktober 3 [email protected] Тел.:89243788800 "Komsomolets" str. 30 4 OOO «Bukachachinsky Izvestyank» Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Verkholenskaya str., 4 8(3022) 23-21-54 Zabaykalsky Krai, Alexandrovo-Zavodsky district,. Mankechur village, ul. 5 SZ "Mankechursky" 8(30240)4-62-41 Tsentralnaya 6 OOO "Zabaykalagro" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Gaidar str., 13 8-914-120-29-18 7 PSK ''Pole'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky region, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 8 OOO "Mysovaya" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 9 OOO "Urulyungui" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Dosatuy,Lenin str., 19 B 89245108820 10 OOO "Xin Jiang" Zabaykalsky Krai,Urban-type settlement Priargunsk, Lenin str., 2 8-914-504-53-38 11 PK "Baygulsky" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chernyshevsky District, Baygul, Shkolnaya str., 6 8(3026) 56-51-35 12 ООО "ForceExport" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Polzunova str. , 30 building, 7 8-924-388-67-74 13 ООО "Eсospectrum" Zabaykalsky Krai, Aginsky district, str. 30 let Pobedi, 11 8-914-461-28-74 [email protected] OOO "Chitinskaya -

Çîëîòîé Àëòàé Ббк 65.291.82 К29

Çîëîòîé Àëòàé ББК 65.291.82 К29 Каталог создан Издательским домом «Алтапрессс» по заказу Администрации Алтайского края под об- щей редакцией доктора технических наук профес- сора М. Щетинина. Консультанты: Д. Батейкин, заместитель начальника Главного управления экономики и инвестиций Алтайского края, начальник управления государственного заказа; Л. Минаева, начальник отдела формирования и раз- мещения государственного заказа Главного управ- ления экономики и инвестиций Алтайского края. Все права сохранены. Полное или частичное вос- произведение, передача в любой форме возможны только после получения предварительного пись- менного разрешения обладателя авторских прав. ИД «Алтапресс» © 2009 ISBN 978-5-904061-05-0 Àäðåñ ÈÄ «Àëòàïðåññ»: 656049, ã.Áàðíàóë, óë.Êîðîëåíêî, 105. Òåë: +7 (3852) 63-15-10 Ôàêñ: +7 (3852) 63-91-30 www.altapress.ru Ýë. ïî÷òà: [email protected] АлтайскийÀëòàéñêèé край êðàé КаталогÊàòàëîã товаров òîâàðîâ AltaiAltai region Krai CatalogueCatalogue of of produced Goods Издательский дом Custom-designed «Алтапресс» for Altai Krai Èçäàòåëüñêèé äîì Publishing House по заказу Administration «Àëòàïðåññ»Администрации “Altapress”by Altapress ïîАлтайского çàêàçó края toPublishing order House Àäìèíèñòðàöèè of Altai Krai Îòïå÷àòàíî â òèïîãðàôèè Àëòàéñêîãî êðàÿ Administration ÈÄ «Àëòàïðåññ» 2009 Òåë: +7 3852 658197 Ôàêñ: +7 3852 633384 Ýë. ïî÷òà: [email protected] 2009 Äèðåêòîð òèïîãðàôèè — Ñ. Ëèïîâèê АлтайскийÀëòàéñêèé крайêðàé КаталогÊàòàëîã товаров òîâàðîâ Altai Krairegion CatalogueCatalog u of e of Goods produced Губернатор Алтайского края А. Б. Карлин Altai Krai governor Alexander B. Karlin Àëòàéñêèé êðàé Êàòàëîã òîâàðîâ Дорогие друзья! Dear friends: Altai region Catalog u e of produced Позвольте представить вам уникальное издание — ката- Let me present this unique edition to you: it is the catalogue лог пользующихся спросом высококачественных товаров, of high-quality and called-for goods produced by Altai lead- выпускаемых ведущими предприятиями Алтайского края. -

Editorial Board

BULLETIN OF MEDICAL SCIENCE 4 (12) 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-in-chief Editorial board Saldan Igor Petrovich Briko Nikolai Ivanovich Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Academician of the RAS, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Deputy editor-in-chief Zharikov Aleksandr Yuryevich Voeyvoda Mikhail Ivanovich Doctor of Biological Sciences, Associate Professor Academician of the RAS, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Organizing editor Kiselev Valery Ivanovich Dygai Aleksandr Mikhailovich Corresponding member of the RAS, Doctor of Medical Academician of the RAS, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Sciences, Professor Professor Executive editor Zlobin Vladimir Igorevich Shirokostup Sergei Vasilyevich Academician of the RAS, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Scientific editors Lobzin Yury Vladimirovich Shoikhet Yakov Nahmanovich Academician of the RAS, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Corresponding member of the RAS, Doctor of Medical Professor Sciences, Professor Onishchenko Gennady Grigoryevich Bryukhanov Valery Mikhailovich Academician of the RAS, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Professor Kolyado Vladimir Borisovich Polushin Yury Sergeyevich Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Academician of the RAS, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Lukyanenko Natalya Valentinovna Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Rakhmanin Yury Anatolyevich Academician of the RAS, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor Responsible for translation Shirokova Valeriya Olegovna Editorial