Petrovsky.Pdf (958.9Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First Name Surname

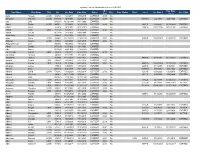

To find your name, click 'ctrl' + 'F' and type your surname. If you entered after 20/02/20 you will not appear on this list, an updated version will be put online on or around the 28/02/20. Runners cannot move into an earlier wave, but you are welcome to move back to a later wave. You do NOT need to inform us of your decision to do this. If you have any problems, please get in touch by phoning 01522 699950. COLOUR RACE APPROX TO THE START WAVE NO. START TIME 1 BLUE A 09:10 2 RED A 09:10 3 PINK A 09:15 4 GREEN A 09:20 5 BLUE B 09:32 6 RED B 09:36 7 PINK B 09:40 8 GREEN B 09:44 9 BLUE C 09:48 10 RED C 09:52 11 PINK C 09:56 12 GREEN C 10:00 VIP BLACK Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First name Surname 11 Pink 1889 Rebecca Aarons Any Black 1890 Jakob Abada 2 Red 4 Susannah Abayomi 3 Pink 1891 Yassen Abbas 6 Red 1892 Nick Abbey 10 Red 1823 Hannah Abblitt 10 Red 1893 Clare Abbott 4 Green 1894 Jon Abbott 8 Green 1895 Jonny Abbott 12 Green 11043 Pamela Abbott 6 Red 11044 Rebecca Abbott 11 Pink 1896 Leanne Abbott-Jones 9 Blue 1897 Emilie Abby Any Black 1898 Jennifer Abecina 6 Red 1899 Philip Abel 7 Pink 1900 Jon Abell 10 Red 600 Kirsty Aberdein 6 Red 11045 Andrew Abery Any Black 1901 Erwann ABIVEN 11 Pink 1902 marie joan ablat 8 Green 1903 Teresa Ablewhite 9 Blue 1904 Ahid Abood 6 Red 1905 Alvin Abraham 9 Blue 1906 Deborah Abraham 6 Red 1907 Sophie Abraham 1 Blue 11046 Mitchell Abrams 4 Green 1908 David Abreu 11 Pink 11047 Kathleen Abuda 10 Red 11048 Annalisa Accascina 4 Green 1909 Luis Acedo 10 Red 11049 Vikas Acharya 11 Pink 11050 Catriona Ackermann -

Winter Newsletter *NEW

WINTER 2021 Changing lives, one child at a time. The entire board joins me in thanking business, industry, development and Melanie for her dedicated leadership communication. Operations manager during this time and for growing the Lisa Masterson and communications board and organization to new heights manager Jen Nagorski have developed over the last three years. tools to revolutionize our mission We are always looking to expand planning and engagement with the breadth of our global partnerships, volunteers and donors. Executive but this year we will also focus on the director Megan Sparks will continue depth and variety of support we can to develop and refine the live online offer. We continue to develop strategic lecture series that she spearheaded partnerships, like those that have allowed in 2020 reaching partners in Zambia, From the board chair us to begin 2021 by sending $40,000 Ethiopia and Liberia. in supplies to our Liberian partners at I look back on 2020 with immeasurable For Children’s Surgery International, Firestone Duside Hospital and helping gratitude for the commitment and 2020 was a year of introspection and develop an on-site medical clinic for LEAD ingenuity demonstrated by our partners, re-imagination; 2021 will be a year of Monrovia Football Academy. donors and volunteers. On behalf of the expansion and innovation. Our dedicated surgeon partners in board of directors, thank you for all your In February 2020, the board Ethiopia have shared their stories of contributions to CSI. We head into 2021 undertook the work of updating our independent success. Their ability to looking for new ways in which we can add mission statement and vision, which immediately and expertly compensate value for our partner sites and pursue were immediately put to the test by the for the absence of western teams with our vision: To reduce global health care global pandemic. -

Most-Common-Surnames-Bmd-Registers-16.Pdf

Most Common Surnames Surnames occurring most often in Scotland's registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths Counting only the surname of the child for births, the surnames of BOTH PARTIES (for example both BRIDE and GROOM) for marriages, and the surname of the deceased for deaths Note: the surnames from these registers may not be representative of the surnames of the population of Scotland as a whole, as (a) they include the surnames of non-residents who were born / married / died here; (b) they exclude the surnames of residents who were born / married / died elsewhere; and (c) some age-groups have very low birth, marriage and death rates; others account for most births, marriages and deaths.ths Registration Year = 2016 Position Surname Number 1 SMITH 2056 2 BROWN 1435 3 WILSON 1354 4 CAMPBELL 1147 5 STEWART 1139 6 THOMSON 1127 7 ROBERTSON 1088 8 ANDERSON 1001 9 MACDONALD 808 10 TAYLOR 782 11 SCOTT 771 12 REID 755 13 MURRAY 754 14 CLARK 734 15 WATSON 642 16 ROSS 629 17 YOUNG 608 18 MITCHELL 601 19 WALKER 589 20= MORRISON 587 20= PATERSON 587 22 GRAHAM 569 23 HAMILTON 541 24 FRASER 529 25 MARTIN 528 26 GRAY 523 27 HENDERSON 522 28 KERR 521 29 MCDONALD 520 30 FERGUSON 513 31 MILLER 511 32 CAMERON 510 33= DAVIDSON 506 33= JOHNSTON 506 35 BELL 483 36 KELLY 478 37 DUNCAN 473 38 HUNTER 450 39 SIMPSON 438 40 MACLEOD 435 41 MACKENZIE 434 42 ALLAN 432 43 GRANT 429 44 WALLACE 401 45 BLACK 399 © Crown Copyright 2017 46 RUSSELL 394 47 JONES 392 48 MACKAY 372 49= MARSHALL 370 49= SUTHERLAND 370 51 WRIGHT 357 52 GIBSON 356 53 BURNS 353 54= KENNEDY 347 -

Surnames in Bureau of Catholic Indian

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Montana (MT): Boxes 13-19 (4,928 entries from 11 of 11 schools) New Mexico (NM): Boxes 19-22 (1,603 entries from 6 of 8 schools) North Dakota (ND): Boxes 22-23 (521 entries from 4 of 4 schools) Oklahoma (OK): Boxes 23-26 (3,061 entries from 19 of 20 schools) Oregon (OR): Box 26 (90 entries from 2 of - schools) South Dakota (SD): Boxes 26-29 (2,917 entries from Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records 4 of 4 schools) Series 2-1 School Records Washington (WA): Boxes 30-31 (1,251 entries from 5 of - schools) SURNAME MASTER INDEX Wisconsin (WI): Boxes 31-37 (2,365 entries from 8 Over 25,000 surname entries from the BCIM series 2-1 school of 8 schools) attendance records in 15 states, 1890s-1970s Wyoming (WY): Boxes 37-38 (361 entries from 1 of Last updated April 1, 2015 1 school) INTRODUCTION|A|B|C|D|E|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|Q|R|S|T|U| Tribes/ Ethnic Groups V|W|X|Y|Z Library of Congress subject headings supplemented by terms from Ethnologue (an online global language database) plus “Unidentified” and “Non-Native.” INTRODUCTION This alphabetized list of surnames includes all Achomawi (5 entries); used for = Pitt River; related spelling vartiations, the tribes/ethnicities noted, the states broad term also used = California where the schools were located, and box numbers of the Acoma (16 entries); related broad term also used = original records. Each entry provides a distinct surname Pueblo variation with one associated tribe/ethnicity, state, and box Apache (464 entries) number, which is repeated as needed for surname Arapaho (281 entries); used for = Arapahoe combinations with multiple spelling variations, ethnic Arikara (18 entries) associations and/or box numbers. -

1 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME: Michael Parkin DATE of BIRTH

CURRICULUM VITAE (October 2011) NAME: Michael Parkin DATE OF BIRTH: February 21, 1939 MARITAL STATUS: Married: Dr. Robin Bade Children: Catherine (1964), Richard (1965), Ann (1967) CITIZENSHIP: Canadian, British, Australian HOME ADDRESS: 128 Bloomfield Drive, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 1P3 Telephone: 519-657-2622 Facsimile: 519-657-4751 BUSINESS ADDRESS: Department of Economics, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 5C2 Telephone: 519-661-3500 Facsimile: 519-661-3666 EDUCATION: 1952-55 Barnsley Secondary Technical School 1955-60 Correspondence courses 1960-63 University of Leicester DEGREES HELD: 1960 Associate of Institute of Management Accountants AIMA 1963 B.A. (Leicester), First class honors 1970 M.A. Economics (Manchester) 2010 D. Litt. (Leicester), Honorary APPOINTMENTS: 1955-1960 Cost accountancy in steel industry 1963-1964 Assistant Lecturer, University of Sheffield 1964-1966 Lecturer, University of Leicester 1967-1969 Lecturer, University of Essex 1969-1970 Senior Lecturer, University of Essex 1970-1975 Professor, University of Manchester 1975-2004 Professor, University of Western Ontario 2004- Professor Emeritus, University of Western Ontario 1 VISITING APPOINTMENTS: 1972 Visiting Professor, Brown University 1973 Visiting Professor, University of New South Wales 1973 Visiting Senior Research Economist, Reserve Bank of Australia 1974 Visiting Professor, Osmania University, Hyderabad, India 1979-1980 Visiting Fellow, Hoover Institution, Stanford University 1983 Visiting Scholar from Abroad, Bank of Japan, Tokyo 1991 Visiting Professor, Bond University, Australia 1992-1993 Norwich Australia Visiting Professor, Bond University, Australia 1993 Erskine Visiting Fellow, Canterbury University, Christchurch, New Zealand 1994 Visiting Professor, Bond University, Australia 1995 Visiting Professor, Bond University, Australia RESEARCH GRANTS AND AWARDS: 1968-1970 The Portfolio Behaviour of the U.K. -

Cayuga County Surname and Family Files in Town and Organization Collections

Cayuga County Surname and Family Files In town and organization collections A B C D E F G 1 Surname Cayuga County Genoa Moravia Town of Town of Montezuma 2 x = family name on file Historian Hist. Assn. COLHS Sterling Victory Hist. Society 3 4 Moravia names also online @ www.colhs.org/p/surnames see 5 Montezuma names online @ www.montezumagen.com website 6 7 Abbe x 8 Abbott x x x x 9 Abbott-Nuitt x 10 Abraham(s) x 11 Abrams x x x 12 Acers x 13 Acker x 14 Ackerman x x 15 Ackerson x x x 16 Ackles x 17 Ackley x 18 Acre x 19 Adams x x x x 20 Adams-Crofoot x 21 Addy x 22 Adessa x 23 Adkins x 24 Adle x 25 Adolph x 26 Adriance x x 27 Adsitt x 28 Agree x 29 Aiken/Aikin x 30 Aikin x 31 Akin x 32 Akin (Aiken) x 33 Albertson x 34 Albie/Albee x 35 Albring x 36 Albro x 37 Alcorn x 38 Alcott/Alcox x 39 Alden x 40 Aldrich x x 41 Aldridge x 42 Alexander x x 43 Alfred x 44 Alger/Algur x 45 Algert x 46 Alifieri x 47 Alissandrello x 48 Allanson x 49 Allee x 50 Allen x x x x x 51 Alley x 52 Allis x 53 Almy x 54 Alnutt x x Cayuga County Surname and Family Files In town and organization collections A B C D E F G 1 Surname Cayuga County Genoa Moravia Town of Town of Montezuma 2 x = family name on file Historian Hist. -

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL -

Updated License Verification List As of 1/8/2019 CE's Exp

Updated License Verification List as of 1/8/2019 CE's Exp. Date Last Name First Name Title Lic. Lic. Date Exp. Date Status Disc Disc. Status Title 2 Lic. 2 Lic. Date 2 Lic. 2 Stat. Due Lic. 2 Aalto Pamela LCSW 6827-C 12/4/2014 9/30/2019 CURRENT 2019 No Aaronson Marynne LCSW 01969-C 10/3/1994 2/28/2019 CURRENT 2019 No 00837-S 2/2/1989 2/28/1995 EXPIRED Aas Leila 00402-A 12/16/1988 8/31/1996 EXPIRED No Abbey Denise LCSW 4854-C 9/1/2005 10/31/2019 CURRENT 2019 No 2907-S 6/6/2000 10/31/2006 EXPIRED Abbot Karen 2506-S 12/5/1997 12/31/2001 EXPIRED No 199P-S 10/17/1997 12/05/1997 EXPIRED Abbott Coby LSW 6511-S 8/6/2013 12/31/2019 CURRENT 2020 No Abbott Loretta 01720-S 7/14/1993 4/30/1998 EXPIRED No Abderrazik Surrey 4984-S 5/31/2006 6/30/2012 EXPIRED No Abdo Maria LCSW 5896-C 10/12/2010 11/30/2019 CURRENT 2020 No 5297-S 10/23/2007 11/30/2010 EXPIRED Abdullah Sandra LCSW 2859-C 2/29/2000 2/28/2019 CURRENT 2020 No Abdullah-hasan John 5095-C 10/6/2006 4/30/2015 EXPIRED No Abear Brenda 01546-S 3/23/1992 3/31/1993 EXPIRED No Abel Nancy 01092-S 9/28/1989 11/30/2013 EXPIRED No Abercrombie Mariah LSW 7439-S 3/9/2017 12/31/2019 CURRENT 2019 No Abernathy Gregory 2470-S 9/15/1997 3/31/2016 EXPIRED No Abhyankar Danielle 4107-S 10/11/2001 9/30/2012 EXPIRED No 440P-S 8/29/2001 10/11/2001 EXPIRED Abraha Surafel LSW 6592-S 12/6/2013 8/31/2019 CURRENT 2020 No Abraham Ermias LSW 4949-S 3/14/2006 6/30/2019 CURRENT 2020 No 656P-S 10/14/2005 12/10/2005 EXPIRED Abraham Jeffrey 4790-S 6/7/2005 4/30/2018 EXPIRED No 620P-S 5/13/2005 6/7/2005 EXPIRED Abrams Betty 00838-S -

Charles S. Peirce and the Philosophy of Science Papers from the Harvard Sesquicentennial Congress

Page iii Charles S. Peirce and the Philosophy of Science Papers from the Harvard Sesquicentennial Congress Edited by Edward C. Moore Page iv Copyright © 1993 by The University of Alabama Press Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487–0380 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencePermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984. Library of Congress Catalogingin Publication Data Charles S. Peirce and the philosophy of science : papers from the Harvard Sesquicenten nial Congress / edited by Edward C. Moore. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 081730665X 1. Science—Philosophy—Congresses. 2. Peirce, Charles S. (Charles Sanders), 1839–1914—Congresses. I. Moore, Edward C. (Edward Carter), 1917 . Q174.C46 1993 501—dc20 9228877 British Library Cataloguingin Publication Data available Page v To Arthur W. Burks with many thanks Page vi I no longer think, as I once did, that there is a difference between science and metaphysics . as long as a metaphysical theory can be rationally criticized. —Karl R. Popper Page vii CONTENTS Preface xi Acknowledgments xiii Abbreviations xv Introduction: Charles S. Peirce and the Philosophy of Science 1 Edward C. Moore Part 1. Logic and Mathematics 1. Peirce on the Conditions of the Possibility of Science 17 C. F. Delaney 2. Peirce's Realistic Approach to Mathematics: Or, Can One Be a Realist 30 without Being a Platonist? Claudine EngelTiercelin 3. Peirce as Philosophical Topologist 49 R. Valentine Dusek 4. -

Index to St. Louis, Missouri Naturalization Records Created After Sept

Index to St. Louis, Missouri Naturalization Records Created after Sept. 27, 1906 Alphabetical surname index N–R History & Genealogy Department St. Louis County Library 1640 S. Lindberg Blvd. St. Louis, Missouri 63131 314-994-3300, ext. 2070 [email protected] Index to St. Louis, Missouri Naturalization Records Created after Sept. 27, 1906 This index covers St. Louis, Missouri naturalization records created between October 1, 1906 and December 1928 and is based on the following sources: • Naturalizations, U.S. District Court—Eastern Division, Eastern Judicial District of Missouri, Vols. 1 – 82 • Naturalizations, U.S. Circuit Court— Eastern Division, Eastern Judicial District of Missouri, Vols. 5 – 21 Entries are listed alphabetically by surname, then by given name, and then numerically by volume number. Abbreviations and Notations SLCL = History and Genealogy Department microfilm number (St. Louis County Library) FHL = Family History Library microfilm number * = spelling taken from the signature which differed from name in index. How to obtain copies Photocopies of indexed articles may be requested by sending an email to the History and Genealogy Department at [email protected]. A limit of three searches per request applies. Please review the library's lookup policy at https://www.slcl.org/genealogy-and-local- history/services. A declaration of intention may lead to further records. For more information, contact the National Archives at the address below. Include all information listed on the declaration of intention. National Archives, Central Plains Region 400 W. Pershing Rd. Kansas City, MO 64108 (816) 268-8000 [email protected] History Genealogy Dept. Index to St. Louis, Missouri Naturalization Records St. -

Participant List

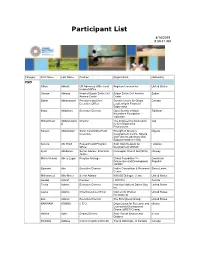

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

World War Ii and Korean Casualties

WORLD WAR II AND KOREAN CASUALTIES LAST NAME FIRST NAME COMMENT DATE ABBOTT BOB MISSING IN ACTION 8/20/1953 ABBOTT ROBERT PRISONER ABBOTT ROBERT N ARMY MISSING 6/21/1951 ABBOTT ROBERT N MISSING NOW IN PRISON CAMP 12/19/? ABBOTT ROBERT N MISSING NOW IN PRISON CAMP 12/20/51 DC ABBOTT ROBERT N PRISONER LIST 12/20/1951 ABBOTT ROBERT N PRISONER LIST 12/20/1951 ABBOTT ROBERT N. PRISONERS OF WAR KOREA 1/12/1953 ABBOTT ROBERT N. HOPES RISE FOR RETURN OF 9 POW'S 6/8/1953 ABBOTT ROBERT N. KIN EAGERLY WAIT NEWS 7/27/1953 ABBOTT ROBERT N. PRISONER OF WAR 4/7/1953 09/04+05/19 ABBOTT ROBERT N. PRISONERS RELEASED 53 ABBOTT ROBERT N. FAMILIES KEEP PRAYERFUL FOR WORD 9/4/1953 ABEL ROBERT T MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 ACHZET DAVID RETURNS TO HOSPITAL N/A ADAMS MERLE E MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 ADAMS ROBERT H MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 ADOLPHSON RICHARD CARL MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 ADORANTE DANTE WILLIAM MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 AGAN JOHN D KILLED IN PHILIPPINES 10/12/48 BODY RETURNED - DIED IN PACIFIC AGAN JOHN D THEATER 9/11/48 AGAN JOHN DICKES MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 AGNEILO EMMANUEL W ARMY DEAD N/A DIED IN EUROPEAN THEATER - REMAINS AGNELLO EMANUEL P. RETURNED TO U.S. 7/3/48 AGNELLO EMANUELE P MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 AGNELLO EMANUELE WILLIAM MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 AGOSTINELLI FRANK SLIGHTLY WOUNDED 9/30/1951 AKEL JOSEPH C WOUNDED 9/3/1951 Page 1 WORLD WAR II AND KOREAN CASUALTIES LAST NAME FIRST NAME COMMENT DATE AKINS JAMES E MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 ALBANESE NICHOLAS MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 ALBANESE TONY MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 ALBRECHT ELROY C MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 ALBREGTS AUGUST H MONROE COUNTY DEAD 5/29/64 ALBRIGHT GERALD STATIONED IN GERMANY 1/10/1953 ALBRIGHT JAMES H.