2007-2008 Annual Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angela Fraleigh

ANGELA FRALEIGH BORN 1976 Beaufort, SC EDUCATION 2003 Master of Fine Arts, Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT 1998 Bachelor of Fine Arts, Boston University, Boston, MA SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL (forthcoming) Inman Gallery Houston, TX (forthcoming) The Darkness Still Has Work To Do, Reading Public Museum, Reading, PA (forthcoming) Shadows Searching for Light, Swope Art Museum, Terre Haute, IN 2019 Sound the Deep Waters, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE 2018 Shadows Searching for Light, Edward Hopper House Museum, Nyack, NY The Bones of Us Hunger for Nothing, Sordoni Art Gallery, Wilkes University, Wilkes- Barre, PA 2017 Watching the Moon Move, 527 Madison Ave, New York, NY The Breezes at Dawn Have Secrets to Tell, Peters Projects, Santa Fe, NM 2016 Between Tongue and Teeth, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY 2015 Lost in the Light, Vanderbilt Mansion, Hyde Park, NY 2014 Ghosts in the Sunlight, Inman Gallery, Houston, TX 2011 by the time I tell you it will all be forgotten, Inman Gallery, Houston, TX far as my eyes could see, University of the Arts, Philadelphia, PA 2008 and I would shine in answer/ being/ without becoming, PPOW Gallery, New York, NY 2007 not one girl it think/ who looks on the light of the sun/ will ever have wisdom/ like this, Inman Gallery, Houston, TX even, Heimbold Visual Art Center, Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, NY if not, winter, James Harris Gallery, Seattle, WA 2006 then, for just a moment, Moravian College, Bethlehem, PA there i still my thirst, Women -

The Golden Blade

THE GOLDEN BLADE FREEeO^I >W^gESTfNy+ FREEDOM AND DESTINY THE STARS OF THE YEAR T H E G O L D E N B L A D E FORTY-SECOND (1990) ISSUE CONTENTS A d a m B i t d e s t o n W i l l i a m F o r w a r d Editorial Notes W. F. Man, Offspring of the World of Stars Rudolf Steiner The Observation of the Stars as a Path to Freedom John Meeks and Michael Brinch The Life between Death and Re-birth in the Light of Astrology Elizabeth Vreede The Bridge of the Green Snake A. Bockemiihl Some Questions concerning Rainer Maria Rdke R. Lissau The Tasks and Deeds in the Life of William Mann (1861n —1925). Heo f descnbeditas"apathofknowledge,R u d o l f to guideS the t e spiritual i n e r Roswitha Spence in the human being to the spiritual in the universe". W i l l i a m M a n n — T h e T e a c h e r T e d R o b e r t s Addiction as an Impulse towards the Renewal of Culture The aitn of this Annual is to bring the outlook of Anthroposophy to bear J. van der Haar on questions and activities of evident relevance to the present, in a way which On the Destiny of the American Indian Brian Gold Book Review may have lasting value. It was founded in 1949 by Charles Davy and Arnold Notes and Acknowledgements Freeman, who were its first editors. -

Chapter I : Introduction 1 Overview 1 Review of Literature 3 Methods 12 Research Aims 15 Conclusion 16 References 17

EXAMINING THE MEASUREMENT OF RACE AND ETHNICITY TO INFORM A MODEL OF SOCIOCULTURAL STRESS AND ADAPTIVE COPING by Rashid S. Njai A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Health Behavior and Health Education) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Harold W. Neighbors, Chair Professor James S. Jackson Professor Robert M. Sellers Associate Professor Cleopatra H. Caldwell Professor David R. Williams, Harvard University “The Ink of the Scholar is worth more than the Blood of the Martyr" -Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Unto Him) © Rashid S. Njai All rights reserved 2008 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all those who have come before me and all those who will hopefully follow in the pursuit of physical, mental and spiritual freedom. This is a tribute to the countless numbers of individuals who died seemingly in vain, but are not forgotten by those of us who remember their struggle for freedom. I remember the struggles you encountered. I attempt everyday to be mindful in my life of the choice you made to fight for your freedom, in whatever way you could. I offer this humble attempt at trying to make some sense of where our people are now, because of your sacrifices. I appreciate what you were able to persevere and overcome so that I could be here and make my attempt at freedom. I have met others who acknowledge your struggles and who similarly hold deeply a responsibility to attempt to bear the fruit of your labors. I continue to seek refuge with others who intend to work the soil of our people in order to reap what you have sowed for our future. -

Karim Al-Zand William Bolcom Anthony Brandt

NEW MUSIC AT RICE ' ... presents a concert of works by .. ' guest composer DAVID COLSON and by ..., KARIM AL-ZAND ·~ ! WILLIAM BOLCOM ANTHONY BRANDT .' RICHARD LA VENDA ' . .,. Thursday, December 2, 2004 8:00 p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall ...... •• RICE UNIVERSITY I • PROGRAM . ., . Second Sonata for Violin and Piano (1978) William Balcom ,.. Summer Dreams (b. 1938) Brutal -fast " Adagio In Memory of Joe Venuti ... ... Sergiu Luca, violin -~,. Susan Archibald, piano .. Mandala (2004; Premiere) David Colson (b.1957) Elizabeth Landon, flute • (J Nicholas Masterson, oboe Louis DeMartino, clarinet ... Adam Trussell, bassoon .- Jonas VanDyke, horn ... The Dragon and the Undying (2004) Anthony Brandt (Poetry by Siegfried Sassoon) (b. 1964) The Dragon and the Undying ' Slumber Song . Karol Bennett, soprano (guest) • Enso String Quartet .. Maureen Nelson, violin Robert Brophy, viola Tereza Stanis/av, violin Richard Belcher, cello •· INTERMISSION .., Leila (2001) Karim Al-Zand . (b.1970) Stephen King, baritone Beau Benson, guitar (guest) .... Enso String Quartet Michael Webster, conductor • -1 . Chiaroscuro (2004; Premiere) Richard Lavenda ..... (b. 1955) Leone Buyse, alto flute Paul Ellison, double bass ,. David Colson, vibraphone (guest) Benjamin Kamins, bassoon • PROGRAM NOTES Second Sonata for Violin and Piano . William Bolcom William Bo/corn's Second Sonata for Violin and Piano was premiered in 1978 by Sergiu Luca with the composer at the piano. Like many of Bolcom's ' -; works, it exhibits clear influences ofjazz and popular music. The first move •• ment features a repeating pattern in the bass of the piano. Its rhythm and rocking motion are perhaps a nod to the "Boogie-Woogie"piano tradition, and its harmonic progression has echoes of the blues. -

Trends in American Fiction Morrison & Music

ENG 352:420: Trends in American Fiction Morrison & Music Tuesdays and Thursdays: 11:30 AM-12:50 PM Room: HAH 421 Professor: Dr. Melanie R. Hill Office Hours: Tuesdays from 1:00 PM-2:00 PM and by appointment Location: Hill Hall 512 Phone: (973) 353-5182 Email: [email protected] Course Overview: In an article in The New Yorker entitled, “Toni Morrison and Nina Simone, United in Soul,” Emily Lordi writes, “Toni Morrison was such an exceptional talent and seemed to float so high above the fray, that it’s easy to forget she was a product of her time. But she was profoundly influenced by the work of contemporary musicians. She wanted her writing to emulate, ... ‘all of the intricacy, all of the discipline, that she heard in black musical performance.’” In this course, we will explore Toni Morrison’s canonical oevure from novels, Jazz and Song of Solomon to Sula and Beloved. In addition to Morrison’s works, we will examine the intersection of African American literature and music, as well as race, gender and spirituality. This seminar will juxtapose Morrison’s renowned literature with the performances of black musicians from Nina Simone and Curtis Mayfield to Issac Hayes and Aretha Franklin. As both text and performance, prose and poetry, and literature and music, studying the works of Toni Morrison offers an excellent resource for our investigation of black literary studies. This seminar is designed to give students a profound examination of Toni Morrison’s writing, and involve students in the kinds of research that the discipline of literary studies currently demands, including: working with primary sources and archival materials; reviewing the critical literature; using online databases of historical newspapers, periodicals, and other cultural materials; exploring relevant contexts in literary, linguistic, and cultural history; studying the etymological history and changing meanings of words; experimenting with new methods of computational analysis of texts; and other methodologies. -

RELEASE the POWER Lyrics and Credits

RELEASE THE POWER Lyrics and Credits The Project Regarding artistic endeavors, the Baha’i Writings state: “All Art is a gift of the Holy Spirit. When this light shines through the mind of a musician, it manifests itself in beautiful harmonies. Again, shining through the mind of a poet, it is seen in fine poetry and poetic prose. When the light of the Sun of Truth inspires the mind of a painter, he produces marvellous pictures. These gifts are fulfilling their highest purpose when showing forth the praise of God.” - ‘Abdu’l-Bahá In the summer of 2017, I had the bounty of helping to facilitate a youth empowerment training utilizing the course “Releasing The Powers of Junior Youth” (Book 5) of the Ruhi Institute. The training brought together youth from around the Phoenix metropolitan area to study concepts and quotations from the Baha’i Writings and reflect on how they could use their energies to be of service to their communities, in particular by mentoring those younger than themselves. The training lasted for about 10 days, including intense study, community outreach, visiting and assisting junior youth groups, recreation, and of course ARTS! There were several youth in the training, however, three in particular were very musically inclined - Brian, Tony, and Ally. We ended up making a song on one of the first days of the training (utilizing a beat from the world famous producer, Sabzi) and we had the opportunity to perform it at a Race Unity Day event that evening. It was an awesome experience, and it led to a desire from the youth to create more songs, eventually leading to the idea of producing an album. -

Commencement Exercises of the Forty-Fourth Academic Year SATURDAY, MAY 16, 2015 • 10 A.M

Commencement Exercises of the Forty-Fourth Academic Year SATURDAY, MAY 16, 2015 • 10 A.M. & 5 P.M. GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY The GSU Story Governors State University, a comprehensive public institution, was created to be a model of innovation. After 45 years as an upper-division university, in the Fall of 2014, GSU, while reaffirming its commitment to returning adult students, admitted its first freshman class, opened its first living-learning residence hall, and launched an athletic program. This transformation was based on rigorous research and an unwavering commitment to inclusive excellence. To drive its transformation, GSU reallocated resources to provide first-year students with a strong foundation for academic achievement. Freshmen are taught by full-time, fully committed faculty members – no grad assistants. Composition classes are limited to 18, and other first-year classes do not exceed 30. Planning for the freshman experience led to full-scale educational reform, encompassing academic majors framed by cornerstone and capstone courses with writing, ethics, citizenship, and critical and innovative thinking integrated across the curriculum. GSU’s bold commitment to innovation is further exemplified by the Dual Degree Program. This partnership with 17 Chicagoland community colleges, launched with Kresge Foundation support, is fast becoming a national model for a seamless pathway from Associate degree to Bachelor’s degree. GSU’s five doctoral programs emphasize research-based practice in physical therapy, occupational therapy, nursing, counseling, and leadership. These major systemic changes were accomplished through strategic planning, comprehensive engagement, and a thoughtful business plan. The American Council on Education (ACE) recently presented GSU the 2015 ACE/Fidelity Investments Award for Institutional Transformation. -

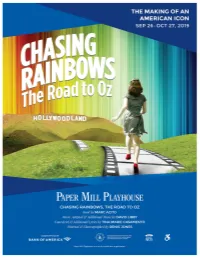

2020-CHASING-RAINBOWS.Pdf

CREATIVE TEAM MARC ACITO (Book) wrote the book of the Broadway musical Allegiance, which New York Newsday recognized for its “well-structured book” and “fully developed characters.” His comedy Birds of a Feather won the Helen Hayes Award for Outstanding New Play. His novel How I Paid for College won the Ken Kesey Award for Fiction. Other musicals include A Room with a View (5th Avenue, Old Globe) and Bastard Jones (the cell), which he will direct as a feature film. A former commentator on NPR’s All Things Considered, Acito has written for The New York Times, Playbill, and American Theatre. NewEdens.nyc DAVID LIBBY (Musical Adaptation, Additional Music, Music Supervision, Arrangements, Orchestrations) is a composer, arranger, and music director. Theater credits include music director for the Off-Broadway production of Play It Cool (Outer Critics Circle Award nomination, Outstanding New Musical) and keyboards on the national tours of Beauty and the Beast and Kiss Me, Kate (2001 revival). David composes music for film and digital media, his credits including Mister Green (Best Short Film, Sci-Fi-London Film Festival), Super Power Blues (PBS affiliate WNET People’s Choice Award), and online episodes of Marvel Entertainment’s The Incredible Hulk and Spider- Man. BA, Bowdoin College. MM, Jazz Studies, Rutgers University. TINA MARIE CASAMENTO (Conceiver, Additional Lyrics) is a teacher, director, producer, and actress with over 30 years’ experience in the industry. She is passionate about creating inspired and emotionally compelling theater. After pitching her concept for Chasing Rainbows and securing the rights, she has spearheaded this musical through numerous workshops, readings, and two developmental productions. -

Watching the Sun Booklet

WATCHING THE SUN How the Ancients Connected with the Sun in Cornwall Editors: Carolyn Kennett (FRAS) and Cheryl Straffon (AKC) Contributors: Ian Cooke . Robin Heath . Lana Jarvis . Carolyn Kennett . Calum MacIntosh . Caeia March . Cheryl Straffon CONTENTS Watching the Sun a Mayes Creative Project 4 Meyn Mamvro 5 Mother and Sun – the Cornish Fogou by Ian Cooke 6 The Solar Ritual Cycle by Cheryl Straffon 11 Solar Aligned Sites in Cornwall by Calum MacIntosh and Cheryl Straffon 18 Eclipse of the Sun by Cheryl Straffon 28 The Mysterious number 19 and the 1999 Cornish Eclipse by Robin Heath 33 Ceremonies of the Sun by Caeia March 37 Green Flashes, Moonbows and Stellar Conjunctions by Cheryl Straffon 39 Winter Solstice at Chûn Quoit by Lana Jarvis and Cheryl Straffon 44 Sun and Moon at Boscawen-ûn by Carolyn Kennett 48 2 Image credits: Front cover: Boscawen-ûn Stone circle, summer solstice sunset (Carolyn Kennett) 3 This page: Boskednan stone circle, summer solstice sunset (Carolyn Kennett) Watching the Sun a Mayes Creative Project Meyn Mamvro Meyn Mamvro (‘Stones of our Motherland’), the magazine of ancient stones and We are very excited to have collaborated with Cheryl Straffon and Meyn Mamvro sacred sites in Cornwall, started publication in 1986, and from the very beginning, to bring together over 30 years of solar inspired articles for you to read. We are one of its interests was the relationship of the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age sure there is something new here to inspire you to get out into the landscape and sites to the cycles of Sun and Moon. -

Late Style, Disability, and the Temporality of Illness in Popular Music

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Singing at Death’s Door: Late Style, Disability, and the Temporality of Illness in Popular Music A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Tiffany Naiman 2017 © Copyright by Tiffany Naiman 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Singing at Death’s Door: Late Style, Disability, and the Temporality of Illness in Popular Music by Tiffany Naiman Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Robert W. Fink, Co-Chair Professor Raymond L. Knapp, Co-Chair This dissertation investigates musical expressions of temporal alterities in works created by popular music artists, identifying their aesthetic responses as their bodies become ill, disabled, and they become more aware of mortality. I propose a critical, hermeneutic, and theoretical method drawn from Edward Said’s appropriation of Adorno’s expression “late style” that I have designated ill style, a form of creativity within a temporality of illness. Late style is discernable in works produced, paradigmatically, at the end of one’s career in “old age,” but late style may also be understood as an influence on artistic output at any stage of life if the subject is experiencing untimeliness and a disruption in access to the communal understanding of futurity and time, a possible consequence of factors other than age. I contend that late style, accelerated by illness, disrupts Western cultural attempts at ignoring precarious and finite nature of existence; the resulting expressions of lateness ask audiences to do the same. I offer a way in which to think more critically about what scholars consider late style, how it functions in popular ii music studies and society, and how it intersects with the fields of disability, gender, queer, and critical race studies, and the social sciences. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Title Page

Celtic Groves Lyric Book TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page THE DIVINE .................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Ancient Mother .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Aphrodite, Dionysus .......................................................................................................................................... 2 3. As You Go ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 4. Cerridwyn's Cauldron ........................................................................................................................................ 3 5. Ecco, Ecco ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 6. Every Woman Born ........................................................................................................................................... 3 7. Freya, Shakti ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 8. Give Thanks ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 9. God Chant (Pan, Poseidon, Dionysus…) -

“Salt Life” Reverend Bill Gause Overbrook Presbyterian Church 5Th Sunday in Ordinary Time February 9, 2020 First Scripture R

“Salt Life” Reverend Bill Gause Overbrook Presbyterian Church 5th Sunday in Ordinary Time February 9, 2020 First Scripture Reading: James 1:22-27 (The Message) 22-24 Don’t fool yourself into thinking that you are a listener when you are anything but, letting the Word go in one ear and out the other. Act on what you hear! Those who hear and don’t act are like those who glance in the mirror, walk away, and two minutes later have no idea who they are, what they look like. 25 But whoever catches a glimpse of the revealed counsel of God—the free life!—even out of the corner of his eye, and sticks with it, is no distracted scatterbrain but a man or woman of action. That person will find delight and affirmation in the action. 26-27 Anyone who sets himself up as “religious” by talking a good game is self-deceived. This kind of religion is hot air and only hot air. Real religion, the kind that passes muster before God the Father, is this: Reach out to the homeless and loveless in their plight, and guard against corruption from the godless world. Second Scripture Reading: Luke 17:11-19 (NRSV) 13“You are the salt of the earth; but if salt has lost its taste, how can its saltiness be restored? It is no longer good for anything, but is thrown out and trampled under foot. 14“You are the light of the world. A city built on a hill cannot be hid. 15No one after lighting a lamp puts it under the bushel basket, but on the lampstand, and it gives light to all in the house.