Selman A. Waksman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oswald Avery and His Coworkers (Avery, Et Al

1984 marks the fortieth anniversary of the publica- tion of the classic work of Oswald Avery and his coworkers (Avery, et al. 1944) proving that DNA is the hereditary molecule. Few biological discoveries rival that of Avery's. He paved the way for the many molecular biologists who followed. Indeed, 1944 is often cited as the beginning of molecular Oswald Avery biology. Having been briefed on the experiments a year before their publication, Sir MacFarlane Burnet and DNA wrote home to his wife that Avery "has just made an extremely exciting discovery which, put rather crudely, is nothing less than the isolation of a pure Charles L. Vigue gene in the form of desoxyribonucleic acid" (Olby 1974). Recalling Avery's discovery, Ernst Mayr said "the impact of Avery's finding was electrifying. I Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/46/4/207/41261/4447817.pdf by guest on 23 September 2021 can confirm this on the basis of my own personal experience . My friends and I were all convinced that it was now conclusively demonstrated that DNA was the genetic material" (Mayr 1982). Scientific dogma is established in many ways. Dis- coveries such as that of the planet Uranus are quickly accepted because the evidence for them is so compel- ling. Some scientific pronouncements are immedi- ately accepted but later found to be erroneous. For example, it was widely accepted in the 1930s, 1940s, and early 1950s that humans had 48 chromosomes; in 1956 it was proven that we have only 46. Some find- ings are not accepted even though, in retrospect, the evidence was compelling. -

The Marion County Tuberculosis Association's

SAVING CHILDREN FROM THE WHITE PLAGUE: THE MARION COUNTY TUBERCULOSIS ASSOCIATION’S CRUSADE AGAINST TUBERCULOSIS, 1911-1936 Kelly Gayle Gascoine Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University May 2010 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________ William H. Schneider, Ph.D., Chair ________________________ Robert G. Barrows, Ph.D. Master’s Thesis Committee ________________________ Stephen J. Jay, M.D. ii Acknowledgments Many people assisted me as I researched and wrote my thesis and I thank them for their support. I would like to thank Dr. Bill Schneider, my thesis chair, for his encouragement and suggestions throughout this past year. Thank you also to the members of my committee, Dr. Bob Barrows and Dr. Stephen Jay, for taking the time to work with me. I would also like to thank the library staff of the Indiana Historical Society for aiding me in my research. iii Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... vi Chapter 1: Tuberculosis in America ................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2: The MCTA Sets Up Shop .............................................................................. -

Martha Chase Dies

PublisherInfo PublisherName : BioMed Central PublisherLocation : London PublisherImprintName : BioMed Central Martha Chase dies ArticleInfo ArticleID : 4830 ArticleDOI : 10.1186/gb-spotlight-20030820-01 ArticleCitationID : spotlight-20030820-01 ArticleSequenceNumber : 182 ArticleCategory : Research news ArticleFirstPage : 1 ArticleLastPage : 4 RegistrationDate : 2003–8–20 ArticleHistory : OnlineDate : 2003–8–20 ArticleCopyright : BioMed Central Ltd2003 ArticleGrants : ArticleContext : 130594411 Milly Dawson Email: [email protected] Martha Chase, renowned for her part in the pivotal "blender experiment," which firmly established DNA as the substance that transmits genetic information, died of pneumonia on August 8 in Lorain, Ohio. She was 75. In 1952, Chase participated in what came to be known as the Hershey-Chase experiment in her capacity as a laboratory assistant to Alfred D. Hershey. He won a Nobel Prize for his insights into the nature of viruses in 1969, along with Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria. Peter Sherwood, a spokesman for Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where the work took place, described the Hershey-Chase study as "one of the most simple and elegant experiments in the early days of the emerging field of molecular biology." "Her name would always be associated with that experiment, so she is some sort of monument," said her longtime friend Waclaw Szybalski, who met her when he joined Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1951 and who is now a professor of oncology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Szybalski attended the first staff presentation of the Hershey-Chase experiment and was so impressed that he invited Chase for dinner and dancing the same evening. "I had an impression that she did not realize what an important piece of work that she did, but I think that I convinced her that evening," he said. -

Milestones and Personalities in Science and Technology

History of Science Stories and anecdotes about famous – and not-so-famous – milestones and personalities in science and technology BUILDING BETTER SCIENCE AGILENT AND YOU For teaching purpose only December 19, 2016 © Agilent Technologies, Inc. 2016 1 Agilent Technologies is committed to the educational community and is willing to provide access to company-owned material contained herein. This slide set is created by Agilent Technologies. The usage of the slides is limited to teaching purpose only. These materials and the information contained herein are accepted “as is” and Agilent makes no representations or warranties of any kind with respect to the materials and disclaims any responsibility for them as may be used or reproduced by you. Agilent will not be liable for any damages resulting from or in connection with your use, copying or disclosure of the materials contained herein. You agree to indemnify and hold Agilent harmless for any claims incurred by Agilent as a result of your use or reproduction of these materials. In case pictures, sketches or drawings should be used for any other purpose please contact Agilent Technologies a priori. For teaching purpose only December 19, 2016 © Agilent Technologies, Inc. 2016 2 Table of Contents The Father of Modern Chemistry The Man Who Discovered Vitamin C Tags: Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier, chemical nomenclature Tags: Albert Szent-Györgyi, L-ascorbic acid He Discovered an Entire Area of the Periodic Table The Discovery of Insulin Tags: Sir William Ramsay, noble gas Tags: Frederick Banting, -

William Barry Wood, Jr

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES W I L L I A M B ARRY WOOD, J R. 1910—1971 A Biographical Memoir by J AMES G. HIRSCH Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1980 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. WILLIAM BARRY WOOD, JR. May 4, 1910-March 9, 1971 BY JAMES G. HIRSCH ARRY WOOD was born May 4, 1910 in Milton, Massachu- B setts, of parents from established Boston families. His father was a Harvard graduate and a business man. Little information is available about Barry's early childhood, but it was apparently an enjoyable and uneventful one; he grew up along with a sister and a younger brother in a pleasant subur- ban environment. He was enrolled as a day student in the nearby Milton Academy, where one finds the first records of his exceptional talents as a star performer in several sports, a brilliant student, and a natural leader. Young Wood had no special interest in science or medicine. He took a science course as a part of the standard curriculum his senior year at Milton and somewhat to his surprise won a prize as the best student in the course. This event signaled the start of his interest in a career in science. In view of his family background and his prep school record it was a foregone conclusion that he would attend Harvard, but Barry was only seventeen years old when he graduated from Milton, and his parents decided he might profit from an opportunity to broaden his outlook and ma- ture further before entering college. -

History of Microbiology Milton Wainwright University of Sheffield Joshua Lederbergl the Rockefeller University

History of Microbiology Milton Wainwright University of Sheffield Joshua Lederbergl The Rockefeller University I. Observations without Application ness of the nature and etiology of disease, with the II. The Spontaneous Generation Controversy result that the majority of the traditional killer dis- III. Tools of the Trade eases have now been conquered. Similar strides IV. Microorganisms as Causal Agents of have been made in the use of microorganisms in Disease industry. and more recently attempts are being made V. Chemotherapy and Antibiosis to apply our knowledge of microbial ecology and VI. Microbial Metabolism and Applied physiology to help solve environmental problems. A Microbiology dramatic development and broadening of the subject VII. Nutrition, Comparative Biochemistry, and of microbiology has taken place since World War II. Other Aspects of Metabolism Microbial genetics, molecular biology, and bio- VIII. Microbial Genetics technology in particular have blossomed. It is to be IX. Viruses and Lysogeny: The Plasmid hoped that these developments are sufficiently op- Concept portune to enable us to conquer the latest specter of X. Virology disease facing us, namely AIDS. Any account of the XI. Mycology and Protozoology, history of a discipline is. by its very nature, a per- Microbiology’s Cinderellas sonal view: hopefully, what follows includes all the XII. Modern Period major highlights in the development of our science. The period approximating 1930-1950 was a ‘vi- cennium” of extraordinary transformation of micro- Glossary biology, just prior to the landmark publication on the structure of DNA by Watson and Crick in 1953. Antibiotics Antimicrobial agents produced b) We have important milestones for the vicennium: living organisms Jordan and Falk (1928) and “System of Bacteriol- Bacterial genetics Study of genetic elements and ogy” (1930) at its start are magisterial reviews of hereditary in bacteria prior knowledge and thought. -

DNA in the Courtroom: the 21St Century Begins

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Massachusetts, School of Law: Scholarship Repository DNA in the Courtroom: The 21st Century Begins JAMES T. GRIFFITH, PH.D., CLS (NCA) * SUSAN L. LECLAIR, PH.D., CLS (NCA) ** In 2004 at the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the structure of DNA, one of the speaKers at a “blacK-tie” gala at the Waldorf Astoria in New YorK City was Marvin Anderson. After having served 15 years of a 210-year sentence for a crime that he did not commit, he became one of only 99 people to have been proven innocent through the use of DNA technology 1. As he walKed off the stage, he embraced Dr. Alec Jeffreys, 2 the man who discovered forensic DNA analysis. 3 * James T. Griffith, Ph.D., CLS (NCA) is the Department Chair of the Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. ** Susan L. Leclair, Ph.D., CLS (NCA) is the chancellor professor in the Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. 1 Innocence Project, Marvin Anderson, http://www.innocenceproject.org/case/display_profile.php?id=99 (last visited (December 14, 2006). 2 Professor Sir Alec John Jeffreys, FRS, is a British geneticist, who developed techniques for DNA fingerprinting and DNA profiling. DNA fingerprinting uses variations in the genetic code to identify individuals. The technique has been applied in forensics for law enforcement, to resolve paternity and immigration disputes, and can be applied to non- human species, for example in wildlife population genetics studies. -

River Flowing from the Sunrise: an Environmental History of the Lower San Juan

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 River Flowing from the Sunrise: An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan James M. Aton Robert S. McPherson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Recommended Citation Aton, James M. and McPherson, Robert S., "River Flowing from the Sunrise: An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan" (2000). All USU Press Publications. 128. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/128 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. River Flowing from the Sunrise An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan A. R. Raplee’s camp on the San Juan in 1893 and 1894. (Charles Goodman photo, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library, University of Utah) River Flowing from the Sunrise An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan James M. Aton Robert S. McPherson Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press all rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 Manfactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper 654321 000102030405 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aton, James M., 1949– River flowing from the sunrise : an environmental history of the lower San Juan / James M. Aton, Robert S. McPherson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87421-404-1 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-87421-403-3 (pbk. -

Research Organizations and Major Discoveries in Twentieth-Century Science: a Case Study of Excellence in Biomedical Research

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Hollingsworth, Joseph Rogers Working Paper Research organizations and major discoveries in twentieth-century science: A case study of excellence in biomedical research WZB Discussion Paper, No. P 02-003 Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Hollingsworth, Joseph Rogers (2002) : Research organizations and major discoveries in twentieth-century science: A case study of excellence in biomedical research, WZB Discussion Paper, No. P 02-003, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/50229 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu P 02 – 003 RESEARCH ORGANIZATIONS AND MAJOR DISCOVERIES IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY SCIENCE: A CASE STUDY OF EXCELLENCE IN BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH J. -

June 2021 Issue

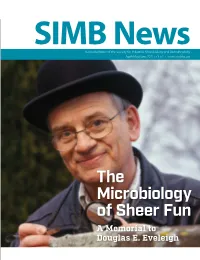

SIMB News News Magazine of the Society for Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology April/May/June 2021 V.71 N.2 • www.simbhq.org The Microbiology of Sheer Fun A Memorial to Douglas E. Eveleigh RAFT® returns to the Hyatt 2021 RAFT® Chairs: Regency Coconut Point Mark Berge, AstraZeneca November 7–10, 2021 Kat Allikian, Mythic Hyatt Regency Coconut Mushrooms Point, Bonita Springs, FL www.simbhq.org/raft contents 34 CORPORATE MEMBERS SIMB News 35 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Melanie Mormile | Editor-in-Chief 36 SIMB STRATEGIC PLAN Elisabeth Elder | Associate Editor Kristien Mortelmans | Associate Editor 38 NEWSWORTHY Vanessa Nepomuceno | Associate Editor 44 FEATURE: DESIGN & PRODUCTION Katherine Devins | Production Manager THE MICROBIOLOGY OF SHEER FUN: A MEMORIAL TO DOUGLAS E. EVELEIGH (1933–2019) BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Steve Decker 60 SBFC 2021 RECAP President-elect Noel Fong 61 SIMB ANNUAL MEETING 2021 Past President Jan Westpheling 62 RAFT® 14 2021 Secretary Elisabeth Elder SIMB WORKSHOPS Treasurer Laura Jarboe 64 Directors Rob Donofrio 65 INDUSTRIAL MICROBIOLOGY MEETS THE MICROBIOME (IMMM) 2021 Katy Kao Priti Pharkya 68 BOOK REVIEW: Tiffany Rau CLIMATE CHANGE AND MICROBIAL ECOLOGY: CURRENT RESEARCH HEADQUARTERS STAFF AND FUTURE TRENDS (SECOND EDITION) Christine Lowe | Executive Director Jennifer Johnson | Director of Member Services 71 CALENDAR OF EVENTS Tina Hockaday | Meeting Coordinator Suzannah Citrenbaum | Web Manager 73 SIMB COMMITTEE LIST SIMB CORPORATE MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION EDITORIAL CORRESPONDENCE 75 Melanie R. Mormile Email: [email protected] ADVERTISING For information regarding rates, contact SIMB News 3929 Old Lee Highway, Suite 92A Fairfax, VA 22030-2421 P: 703-691-3357 ext 30 F:703-691-7991 On the cover Email: [email protected] Doug Eveleigh wearing his father’s www.simbhq.org bowler hat while examining lichens SIMB News (ISSN 1043-4976), is published quarterly, one volume per year, by the on a tombstone. -

Synthetic Biology in Fine Art Practice. Doctoral Thesis, Northumbria University

Citation: Mackenzie, Louise (2017) Evolution of the Subject – Synthetic Biology in Fine Art Practice. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/38387/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html EVOLUTION OF THE SUBJECT SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY IN FINE ART PRACTICE LOUISE MACKENZIE PhD 2017 EVOLUTION OF THE SUBJECT SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY IN FINE ART PRACTICE LOUISE MACKENZIE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaKen in the Faculty of Arts, Design & Social Sciences in collaboration with the Institute of Genetic Medicine at Newcastle University December 2017 ABSTRACT AcKnowledging a rise in the use of synthetic biology in art practice, this doctoral project draws from vital materialist discourse on biotechnology and biological materials in the worKs of Donna Haraway, Jane Bennett, Rosi Braidotti and Marietta Radomska to consider the liveliness of molecular biological material through art research and practice. -

Human Genetics 1990–2009

Portfolio Review Human Genetics 1990–2009 June 2010 Acknowledgements The Wellcome Trust would like to thank the many people who generously gave up their time to participate in this review. The project was led by Liz Allen, Michael Dunn and Claire Vaughan. Key input and support was provided by Dave Carr, Kevin Dolby, Audrey Duncanson, Katherine Littler, Suzi Morris, Annie Sanderson and Jo Scott (landscaping analysis), and Lois Reynolds and Tilli Tansey (Wellcome Trust Expert Group). We also would like to thank David Lynn for his ongoing support to the review. The views expressed in this report are those of the Wellcome Trust project team – drawing on the evidence compiled during the review. We are indebted to the independent Expert Group, who were pivotal in providing the assessments of the Wellcome Trust’s role in supporting human genetics and have informed ‘our’ speculations for the future. Finally, we would like to thank Professor Francis Collins, who provided valuable input to the development of the timelines. The Wellcome Trust is a charity registered in England and Wales, no. 210183. Contents Acknowledgements 2 Overview and key findings 4 Landmarks in human genetics 6 1. Introduction and background 8 2. Human genetics research: the global research landscape 9 2.1 Human genetics publication output: 1989–2008 10 3. Looking back: the Wellcome Trust and human genetics 14 3.1 Building research capacity and infrastructure 14 3.1.1 Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (WTSI) 15 3.1.2 Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics 15 3.1.3 Collaborations, consortia and partnerships 16 3.1.4 Research resources and data 16 3.2 Advancing knowledge and making discoveries 17 3.3 Advancing knowledge and making discoveries: within the field of human genetics 18 3.4 Advancing knowledge and making discoveries: beyond the field of human genetics – ‘ripple’ effects 19 Case studies 22 4.