Globalization and Rapid New Market Growth How the International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Re Urban Outfitters, Inc. Securities Litigation 13-CV-05978-Amended

Case 2:13-cv-05978-LFR Document 11 Filed 03/10/14 Page 1 of 86 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA In ie. Urban Outfitters, Inc. Master File Securities Litigation No 2 l3-c' 05978-1 FR This Document Relates To: All Actions, AMENDED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS Case 2:13-cv-05978-LFR Document 11 Filed 03/10/14 Page 2 of 86 rFAJ311 OF CONTENTS Page 1. SUMMARY OF THE ACTION .......................................................................................... H. JURISDICTION AND VENUE .......................................................................................... 5 111. PARTIES ............................................................................................................................. A. Plaintiff.................................................................................................................... B, Defendants ...............................................................................................................6 IV. SUBSTANTIVE ALLEGATIONS ...................................................................................10 A. Confidential Witnesses .......................................................................................... Jo B. Background of the Company and Its Brands .........................................................12 C. 'Comparable" Sales Growth Is a Key Metric in the Retail Industry..................... 15 I), Leading Up to the Class Period, the Urban Outfitters Brand Achieved -

URBAN OUTFITTERS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended January 31, 2021 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ________ to ________ Commission File No. 000-22754 URBAN OUTFITTERS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Pennsylvania 23-2003332 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 5000 South Broad Street, Philadelphia, PA 19112-1495 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (215) 454-5500 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Shares, par value $.0001 per share URBN NASDAQ Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by checkmark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by checkmark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by checkmark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

About Finch Brands

® about finch brands ABOUT US finch brands is a real-world branding agency. Like the finches whose beaks inspired Darwin’s theory of evolution, brands that adapt to the ever-changing environment not only survive, they thrive. We draw our name and inspiration from the forces that shape the natural world to help our clients succeed in the real world. Finch Brands was founded in 1998 by executives instrumental in the ascent of IKEA and David’s Bridal. Their original vision was to create the firm they were never able to find when they were in our clients’ shoes – an end-to-end brand development and management powerhouse that seamlessly delivers breakthrough brand strategy and irrepressibly creative brand design. To accomplish this, we have brought together a team of leaders from brand- first organizations like Campbell Soup Company, NPR, and Urban Outfitters. These experiences make us a better, more instinctive partner – and we put this hard-earned experience to work for clients across categories and all along the growth track. SERVICES our goal is to be the most consequential partner with whom our clients will ever engage. BRAND DEVELOPMENT BRAND MANAGEMENT vision and mission strategic counsel and growth planning brand strategy brand tracking and brand health brand architecture product/service innovation funnel identity (naming, logo, tagline) pricing brand standards/design systems brand extension / elasticity packaging design and POP advertising campaign development and launch internal brand rollout / training marketing planning / demand generation launch planning and execution social media strategy / program management web design and digital strategy MARKET RESEARCH quantitative surveys focus groups in-depth interviews (IDI) ethnography digital bulletin boards virtual communities in-home research store visits and mystery shopping custom methodologies EXECUTIVE TEAM EXECUTIVE DANIEL ERLBAUM CEO A retailer and business builder, Daniel co-founded Finch Brands after serving as an original investor and Vice President at David’s Bridal. -

COMPANY INDEX WEIGHT ACI Worldwide Inc 0.22% AECOM 0.40% AGCO Corp 0.23% AMC Networks Inc.-A 0.09% ASGN Incorporated 0.19% Aaron's Inc

COMPANY INDEX WEIGHT ACI Worldwide Inc 0.22% AECOM 0.40% AGCO Corp 0.23% AMC Networks Inc.-A 0.09% ASGN Incorporated 0.19% Aaron's Inc. 0.21% Acadia Healthcare Company Inc 0.16% Acuity Brands Inc 0.25% Adient Inc. 0.13% Adtalem Global Education Inc 0.10% Affiliated Managers Grp 0.22% Alleghany Corp (NY) 0.63% Allegheny Technologies Inc 0.14% Allete Inc 0.23% Allscript Healthcare Solutions Inc 0.08% Amedisys Inc 0.35% American Campus Communities Inc 0.35% American Eagle Outfitters 0.13% American Financial Group 0.46% Antero Midstream Corp 0.08% Apergy Corp 0.11% AptarGroup Inc 0.39% Arrow Electronics Inc 0.35% Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Inc 0.23% Ashland Global Holdings Inc 0.26% Associated Banc-Corp (IL) 0.18% AutoNation Inc 0.15% Avanos Medical, Inc 0.08% Avis Budget Group Inc 0.13% Avnet Inc 0.20% Axon Enterprise Inc 0.28% BANK OZK 0.18% BJ's Wholesale Club Holdings 0.14% BancorpSouth Inc (MS) 0.15% Bank of Hawaii Corp 0.20% Bed Bath & Beyond Inc 0.08% Belden Inc 0.11% Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc A 0.44% Bio-Techne Corp 0.42% Black Hills Corp 0.28% Blackbaud Inc 0.21% Boston Beer Inc A 0.20% Boyd Gaming Corp 0.14% Brighthouse Financial Inc 0.27% Brinker Intl Inc 0.09% Brixmor Property Group Inc 0.33% Brown & Brown Inc 0.59% Brunswick Corp 0.29% CACI International Inc 0.37% CDK Global Inc 0.34% CIENA Corp 0.36% CIT Group Inc 0.24% CNO Financial Group Inc 0.16% CNX Resources Corp. -

In Re Innocoll Holdings Public : Ltd

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA : : IN RE INNOCOLL HOLDINGS PUBLIC : LTD. CO. SEC. LITIG. : CIVIL ACTION : : No. 17-341 : MEMORANDUM PRATTER, J. SEPTEMBER 5, 2018 The plaintiffs in this securities class action allege that Innocoll Holdings Public Ltd. Co., Chief Executive Officer Anthony Zook, and Chief Medical Officer Dr. Lesley Russell made misleading statements or omissions about XaraColl, a collagen product the pharmaceutical company was developing during the class period. The defendants allegedly made positive statements about the New Drug Application for XaraColl even though they knew, or recklessly failed to know, that XaraColl contained device components that had not yet been tested. The plaintiffs contend that, by making such statements, the defendants misled investors who relied on the positive statements. The plaintiffs present securities fraud claims against all defendants under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5. They also make individual control liability claims against Mr. Zook and Dr. Russell under Section 20(a). The defendants filed a motion to dismiss all the claims under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6). In doing so, they attached to their motion a declaration from the plaintiffs’ confidential witness, which then prompted the plaintiffs to file a motion to convert the motion to dismiss into one for summary judgment. 1 For the reasons outlined in this Memorandum, the Court: (1) denies the motion to convert and, instead, disregards the declaration; and (2) grants the motion to dismiss with leave to amend because the plaintiffs failed to meet the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act’s heightened pleading standard relating to the element of scienter. -

John Kammerer

John G. Kammerer 12 Lambourne Path (856) 340-0253 Sewell, New Jersey 08080-3142 [email protected] (http://www.linkedin.com/in/johnkammerer) POSITIONING STATEMENT: Driven and resourceful financial executive with a proven track record of providing vision, leadership and innovative solutions to meet business objectives. Over 25 years of broad industry experience including high growth enterprises ranging from start-ups to an equity-backed entity. Key Accomplishments Include: • Created reporting submissions & KPI • Developed & implemented ERP strategies • Executed operational restructuring • Implement business processes & governance • Created shared services • Developed risk management strategies • Implementation of SOX-404 controls • Managing credit risk programs • Design medical benefits program with broker • Annual audit & tax coordination/responsibility SEARCH OBJECTIVE: Divisional Vice President of Finance (start-up to multi-billion revenue company) / Operational CFO (start- up to multi-billion revenue company) role in a public or equity-backed company AREAS of EXPERTISE: Organizational Partnership Financial Management Manufacturing Based ERP Systems Development Budgeting / Forecasting Manufacturing Excellence Staff Development & Succession Financial Reporting & Integrity Lean Manufacturing Process Analytics & Improvement Debt Management Six Sigma – Green Belt Cost & Profitability Improvement Internal Controls Cost Accounting Business Partnering Cost & Risk Management Inventory Control TARGETED COMPANIES: • Aramark • Campbell -

Ngai V. Urban Outfitters, Inc., No. 19-Cv-1480

Case 2:19-cv-01480-WB Document 50 Filed 03/29/21 Page 1 of 44 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA PAUL NGAI AND XIAOYAN NGAI, CIVIL ACTION Plaintiff, v. URBAN OUTFITTERS, INC., LORIE A. NO. 19-1480 KERNECKEL, BARBARA ROZASAS, JOHN DOES 1 THROUGH 10 AND ABC CORPORATIONS 1-10, Defendants. MEMORANDUM OPINION Defendants Urban Outfitters, Inc. (“Urban”), Lorie A. Kerneckel, and Barbara Rozsas (collectively, Defendants) move for summary judgment on Paul Ngai (“Plaintiff” or “Ngai”) and Xiaoyan Ngai’s (together, “Plaintiffs”) claims for national origin and age discrimination, retaliation, and hostile work environment in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII), the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA), the Pennsylvania Human Rights Act (PHRA), and the Philadelphia Fair Practices Ordinance (PFPO), aiding and abetting discrimination in violation of the PHRA and PFPO, whistleblower retaliation in violation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, violation of the Pennsylvania Wage Payment and Collection Law (WPCL), and common law intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED) and loss of consortium.1 In turn, Plaintiffs move for partial summary judgment with respect to Defendants’ affirmative defense that Ngai failed to mitigate damages. For the reasons that follow, Defendants’ motion will be granted in part and denied in part and Plaintiffs’ motion will be denied. 1 Plaintiff abandons his gender-based claims of discrimination, retaliation, and hostile work environment, common law wrongful discharge, and whistleblower retaliation under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in his summary judgment briefing. These claims will therefore be dismissed. -

Customer Margins for Onechicago Futures

#XXXXX TO: ALL CLEARING MEMBERS DATE: August 13, 2018 SUBJECT: Customer Margins for OneChicago Futures On a monthly basis OCC updates OneChicago scan ranges used in the OCX SPAN parameter file. The frequency of the updates is intended to keep the futures customer margin rates more closely aligned with clearing margins, while maintaining regulatory minimums related to security futures. This month’s new rates will be effective on Tuesday 8/21. To receive email notification of these rate changes, which includes an attached file of the rate changes, please subscribe to the ONE Updates list from the OFRA webpage: https://www.theocc.com/risk- management/ofra/ The following scan ranges will be updated and all others will not change: Commodity Name Current Scan Code Scan Range Range Effective 8/21/2018 AAN Aarons Inc 23.0 24.2 AAP ADVANCED AUTO PARTS INCCOM 22.0 24.9 AAXN Axon Enterprise, Inc. 25.2 32.8 ABBV Abbvie Inc. 21.4 20.0 ABC AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 20.0 22.5 ABX BARRICK GOLD CORP 20.0 24.3 ACAD ACADIA PHARMACEUTICALS 31.5 42.1 ACH ALUMINUM CORP CHINA LTDSPON ADR H SHS 21.1 24.0 AEGN Aegion Corp 22.0 25.2 AEM Agnico Eagle Mines Limited 20.0 21.1 AEO AMERICAN EAGLE OUTFITTERS NECOM 20.0 21.2 AFSI AMTRUST FINANCIAL SERVICES ICOM 30.2 35.1 AGIO AGIOS PHARMACEUTICALS INCCOM 30.7 33.7 AGX ARGAN INCCOM 27.3 35.7 AKAM AKAMAI TECHNOLOGIES INCCOM 20.0 22.1 AKRX AKORN INCCOM 38.2 40.7 AKS AK STL HLDG CORP 34.3 38.0 ALKS Alkermes plc 27.4 39.1 ALNY ALNYLAM PHARMACEUTICALS INCCOM 46.5 54.1 ALXN ALEXION PHARMACEUTICALS INC 21.1 22.8 AMAG AMAG Pharmaceuticals Inc 34.4 43.6 AMBA AMBARELLA INCSHS 27.7 32.5 AMD ADVANCED MICRO DEVICES INC 31.7 34.5 AMED AMEDISYS INCCOM 21.9 24.2 AMN AMN HEALTHCARE SERVICES INCCOM 23.2 26.1 AMWD AMERICAN WOODMARK CORPCOM 40.4 26.9 ANET ARISTA NETWORKS INCCOM 24.7 28.3 ANF ABERCROMBIE & FITCH CO 34.8 38.9 AOBC American Outdoor Brands Corporation 22.7 24.6 APEI AMERICAN PUBLIC EDUCATION INCOM 37.0 40.8 APOG APOGEE ENTERPRISES INCCOM 20.0 23.0 ARCO ARCOS DORADOS HOLDINGS INC 22.4 24.4 ATGE Adtalem Global Education Inc. -

Women on Boards the Forum of Executive Women Executive Suites Initiative

Women on Boards The Forum of Executive Women Executive Suites Initiative Improving corporate governance. Increasing shareholder value. The time is NOW. Citizens Bank of Pennsylvania is proud to support The Forum of Executive Women in a variety of ways, including underwriting The Forum's Women on Boards report for 2004. At Citizens Bank, where women comprise 50 percent of our Leadership Team, we believe that diversity, in all of its many manifestations, results in different perspectives, new ideas, and stronger outcomes. In embracing its mission to support colleagues, customers, and community, Citizens Bank applauds The Forum for its leadership in advocating for the advancement of women in our region. About The Forum of Executive Women Founded in 1977, The Forum of Executive Women is a membership organization of 300 women of influence in Greater Philadelphia. Its members hold top positions in every major segment of the community — from finance to manufacturing, from government to healthcare, from not-for-profits to communications, from the professions to technology. As the region's premier women's organization, The Forum fulfills its mission — to advance women leaders in Greater Philadelphia — by supporting women in leadership roles, promoting parity in the corporate world, mentoring young women, and providing a forum for the exchange of views, contacts, and information. The Forum's Executive Suites Initiative advocates and facilitates the increased representation of women on boards and in top management positions of major public companies in our region. Irene H. Hannan, President Sharon Hardy, Executive Director A Four-Year Snapshot of Women On Boards % of women on boards 12% 10% 8% 6% 4% Executive 2% Summary 0% 2000 2001 2002 2003 Ensuring the Research is Current and Comparable Companies in the technology/telecommunications category have the fewest women represented in all levels of Revenues change from year to year. -

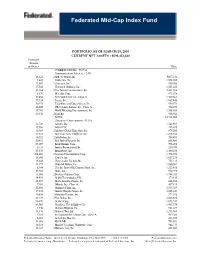

Federated Mid-Cap Index Fund

Federated Mid-Cap Index Fund PORTFOLIO AS OF MARCH 29, 2019 CURRENT NET ASSETS - $593,452,840 Principal Amount or Shares Value COMMON STOCKS - 95.9%1 Communication Services - 2.5% 14,222 2 AMC Networks, Inc. $807,241 1,623 Cable One, Inc. 1,592,780 23,507 2 Cars.com, Inc. 535,960 37,540 Cinemark Holdings, Inc. 1,501,225 51,364 2 Live Nation Entertainment, Inc. 3,263,668 8,570 Meredith Corp. 473,578 39,868 New York Times Co., Class A 1,309,664 77,124 Tegna, Inc. 1,087,448 30,933 Telephone and Data System, Inc. 950,571 16,605 Wiley (John) & Sons, Inc., Class A 734,273 17,961 World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. 1,558,655 26,636 2 Yelp, Inc. 918,942 TOTAL 14,734,005 Consumer Discretionary - 11.5% 21,728 Aaron's, Inc. 1,142,893 33,566 Adient PLC 435,015 18,981 2 Adtalem Global Education, Inc. 879,200 57,672 American Eagle Outfitters, Inc. 1,278,588 10,932 2 AutoNation, Inc. 390,491 50,411 Bed Bath & Beyond, Inc. 856,483 29,097 Boyd Gaming Corp. 796,094 6,331 Brinker International, Inc. 280,970 29,570 Brunswick Corp. 1,488,258 204,681 2 Caesars Entertainment Corp. 1,778,678 16,046 Carter's, Inc. 1,617,276 15,358 Cheesecake Factory, Inc. 751,313 11,971 Churchill Downs, Inc. 1,080,502 8,184 Cracker Barrel Old Country Store, Inc. 1,322,616 51,764 Dana, Inc. 918,293 11,866 2 Deckers Outdoor Corp. -

Strategic Planning Online

Strategic Planning for the real world How to harness the wealth of information, inspiration and insight on the Internet for more resonant, relevant and effective communications Nicholine Hayward April 2009 ͞WĞƌŚĂƉƐLJou will seek out some trove of data and sift through it, balancing your intelligence and intuition to arrive at a glimmering new idea.͟ Steven D Levitt and Stephen J Dubner Freakonomics Introduction The problem with Planning is that we need to know what people want. This means asking them questions, which immediately creates a dilemma. Every group, every, omnibus, survey or depth interview, however carefully planned and objectively moderated, engenders a sense of self- consciousness in the respondents that can skew the results. tĞ͛ǀĞall been to Groups where someone was afraid to speak while another liked the sound of his own voice a bit too much. tŽƵůĚŶ͛ƚŝƚďĞŶŝĐĞƚŽďĞable to ƐĞĞǁŚĂƚǁĂƐŝŶƉĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐŚĞĂĚƐǁŝƚŚŽut having to ask? Would it be good to have data from a larger proportion of the population than the base sizes we normally have? tŝƚŚƚŚĞƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚŵĞƚŚŽĚŽůŽŐLJ/͛ŵĂďŽƵƚƚŽĚĞƐĐƌŝďĞ͕we can. By looking at what millions of people are asking for and talking about online, we have access to the largest, most honest and unself- conscious focus group in the world. We can apply the results of this methodology to every stage of a business and marketing strategy, from developing the products that people are looking for and improving the ones they are already buying, to devising communications campaigns that really strike a chord. We can use it to see market and category dynamics reflected in consumer awareness and demand, to find out what people think about a brand, create rounded and realistic pen portraits and a resonant tone of voice or to gain insights into consumer behaviour ʹ and how best to reach them. -

The Ultimate Guide to Brand Management © Outfit, 2019 All Rights Reserved

The Ultimate Guide to Brand Management © Outfit, 2019 All rights reserved. The Ultimate Guide to Brand Management Table of Contents 01 .What is ‘brand’? ....................................................................................1 02 .The history of ‘brand’ in 2 minutes ......................................................5 03 .The basics of brand management ........................................................9 04 .The importance of brand architecture and heirachy .........................15 05 .Strategies for a house of brands or a branded house ........................19 06 .What does on-brand mean? ...............................................................25 07 .Brand strategy from A to not-quite Z .................................................31 08 .The power of brand integrity ..............................................................57 09 .How good brand management translates to results ..........................63 10 .Brand management in a decentralised environment .........................66 11 .How to ensure brand compliance ......................................................73 12 .How to rebrand ...................................................................................79 13 .What does it mean to debrand? .........................................................92 14 .The biggest challenges for a central marketing team ........................96 15 .How to be more efficient with marketing production ......................102 16 .What is brand automation? ...............................................................108