Energy Transitions Are Brown Before They Go Green

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Re Urban Outfitters, Inc. Securities Litigation 13-CV-05978-Amended

Case 2:13-cv-05978-LFR Document 11 Filed 03/10/14 Page 1 of 86 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA In ie. Urban Outfitters, Inc. Master File Securities Litigation No 2 l3-c' 05978-1 FR This Document Relates To: All Actions, AMENDED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS Case 2:13-cv-05978-LFR Document 11 Filed 03/10/14 Page 2 of 86 rFAJ311 OF CONTENTS Page 1. SUMMARY OF THE ACTION .......................................................................................... H. JURISDICTION AND VENUE .......................................................................................... 5 111. PARTIES ............................................................................................................................. A. Plaintiff.................................................................................................................... B, Defendants ...............................................................................................................6 IV. SUBSTANTIVE ALLEGATIONS ...................................................................................10 A. Confidential Witnesses .......................................................................................... Jo B. Background of the Company and Its Brands .........................................................12 C. 'Comparable" Sales Growth Is a Key Metric in the Retail Industry..................... 15 I), Leading Up to the Class Period, the Urban Outfitters Brand Achieved -

Historic Philadelphia, Inc. 2012 Fall Programming Fact Sheet

PRESS CONTACT: Cari Feiler Bender, Relief Communications, LLC (610) 416-1216, [email protected] HISTORIC PHILADELPHIA, INC. 2012 FALL PROGRAMMING FACT SHEET DESCRIPTION: Historic Philadelphia, Inc. makes our nation’s history relevant and real through interpretation, interaction, and education, strengthening Greater Philadelphia’s role as the destination to experience American history. Historic Philadelphia, Inc.’s Once Upon A Nation brings history to life, featuring Adventure Tours (walking tours), History Makers, Storytelling Benches throughout the Historic District and at Valley Forge, and the Benstitute to specially train all staff. Franklin Square is an outdoor amusement oasis with Philadelphia-themed Mini Golf, the Philadelphia Park Liberty Carousel, and SquareBurger, hosting parties and special events in the new Pavilion in Franklin Square. Liberty 360 , a digital 3-D experience, is a year-round indoor attraction housed at the Historic Philadelphia Center as Phase I of the all-new completely re-imagined Lights of Liberty . The Betsy Ross House allows visitors a personal look at the story and home of a famous historical figure, with newly remodeled and reinterpreted rooms and changing exhibitions. LIBERTY 360: Liberty 360 in the PECO Theater immerses the viewer in the symbols of freedom. Benjamin Franklin appears in a groundbreaking 360-degree, 3-D show unlike anything that has ever been seen before, and escorts the audience on a journey of discovery and exploration of America’s most beloved symbols. The 15-minute, 3-D film surrounds -

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’S Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’s Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David W. Young Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Steven Conn, Advisor Saul Cornell David Steigerwald Copyright by David W. Young 2009 Abstract This dissertation examines how public history and historic preservation have changed during the twentieth century by examining the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1683, Germantown is one of America’s most historic neighborhoods, with resonant landmarks related to the nation’s political, military, industrial, and cultural history. Efforts to preserve the historic sites of the neighborhood have resulted in the presence of fourteen historic sites and house museums, including sites owned by the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the City of Philadelphia. Germantown is also a neighborhood where many of the ills that came to beset many American cities in the twentieth century are easy to spot. The 2000 census showed that one quarter of its citizens live at or below the poverty line. Germantown High School recently made national headlines when students there attacked a popular teacher, causing severe injuries. Many businesses and landmark buildings now stand shuttered in community that no longer can draw on the manufacturing or retail economy it once did. Germantown’s twentieth century has seen remarkably creative approaches to contemporary problems using historic preservation at their core. -

0511House-Urban Affairsmichelle

1 1 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 2 URBAN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE 3 COATESVILLE CITY HALL, COUNCIL CHAMBERS 4 WEDNESDAY, MAY 11, 2016 5 10:00 A.M. 6 PUBLIC HEARING ON BLIGHT 7 8 BEFORE: HONORABLE SCOTT A. PETRI, MAJORITY CHAIR HONORABLE BECKY CORBIN 9 HONORABLE JERRY KNOWLES HONORABLE HARRY LEWIS 10 HONORABLE JAMES R. SANTORA HONORABLE ED NEILSON 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 2 1 COMMITTEE STAFF PRESENT CHRISTINE GOLDBECK 2 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, HOUSE URBAN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE 3 V. KURT BELLMAN 4 RESEARCH ANALYST, DEMOCRATIC COMMITTEE 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 3 1 I N D E X 2 OPENING REMARKS By Chairman Petri 5 - 6 3 By Representative Santora 6 By Representative Knowles 6 - 7 4 By Representative Nielson 7 - 8 5 REMARKS By Chairman Petri 8 - 10 6 OPENING REMARKS 7 By Representative Corbin 10 - 11 By Representative Lewis 11 - 14 8 By Linda Lavender Norris 14 9 DISCUSSION AMONG PARTIES 15 - 19 10 PRESENTATION By Dave Sciocchetti 19 - 22 11 QUESTIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS 23 - 28 12 PRESENTATION 13 By Michael Trio 28 - 38 By Sonia Huntzinger 38 - 42 14 QUESTIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS 42 - 59 15 PRESENTATION 16 By Joshua Young 59 - 65 By Kristin Camp 65 - 70 17 QUESTIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS 70 - 77 18 PRESENTATION 19 By Jack Assetto 78 - 81 By James Thomas 81 - 85 20 QUESTIONS FROM COMMITTEE MEMBERS 85 - 89 21 PRESENTATION 22 By Dr. -

Wells Fargo Center Suite Menu.Pdf

Packages The Bella Vista 525/550 Event Day PACKAGES SERVE APPROXIMATELY 12 GUESTS FEDERAL PRETZELS Philadelphia Classic Sea Salt Soft Pretzels, Spicy Mustard (350 cal per Pretzel) (10 cal per 2 oz Spicy Mustard) POPCORN gf Enhance Your Experience Bottomless Fresh Popped, Souvenir Pail (190 cal per 1 oz serving) To further enhance your experience add one of our other menu favorites. ® UTZ WAVY POTATO CHIPS gf CHICKIE’S & PETE’S ® WORLD FAMOUS Onion Dip ® (280 cal per 1.8 oz Wavy Potato Chips) (150 cal per 1.3 oz Onion Dip) CRAB FRIES gf 54 Cheese Sauce CHICKIE’S & PETE’S ® CUTLETS (1140 cal per 13.3 oz Fries) (130 cal per 2.7 oz Cheese Sauce) Two orders of the World Famous Cutlets, with Honey Mustard & BBQ (1170 cal per 13.4 oz Cutlet) (230 calories per 1.7 oz Honey Mustard) (90 cal per 1.7 oz BBQ) FARMERS’ MARKET SEASONAL CRUDITÉ gf 54 Carrots, Peppers, English Cucumbers, Broccoli, Ranch Dressing SMOKED TURKEY HOAGIE (110 cal per 5.2 oz Vegetables) (80 cal per.85 oz Ranch Dressing) House Smoked Turkey, Herb Cheese Spread, Bacon, Roasted Red Pepper, Arugula, Amoroso ® Seeded Roll (410 cal 9.66 oz Smoked Turkey Hoagie) BEVERAGE PACKAGE #1 170 1 Six-Pack Each of Pepsi, Diet Pepsi, Sierra Mist, PHILLY CHEESESTEAKS Bottled Water and 3 Six-Packs of Domestic Beer of Your Choice “Wit” Sautéed Onions, Cheese Sauce, Amoroso ® Roll (570 cal per 12.31 oz Philly Cheesesteak) SERVES 6 DIETZ & WATSON ® GRILLED ARENA HOT DOGS All Beef Hot Dogs, Sauerkraut, Potato Buns (350 cal per 4.48 oz Hot Dog) (5 cal per oz 1.34 Sauerkraut) (150 cal 1.87 per oz Potato Bun) The calorie and nutrition information provided is for individual servings , FRESH BAKED COOKIES not for the total number of servings on each tray, because serving Chef’s Choice of Fresh Baked Cookies styles e.g. -

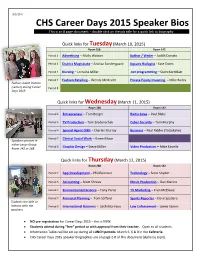

CHS Career Days 2015 Speaker Bios This Is an 8 Page Document – Double Click on the Job Title for a Quick Link to Biography

3/3/15 C CHS Career Days 2015 Speaker Bios This is an 8 page document – double click on the job title for a quick link to biography. Quick links for Tuesday (March 10, 2015) Room 268 Room 142 Period 2 Advertising – Molly Watson Author / Writer – Judith Donato Period 3 District Magistrate – Analisa Sondergaard Aquatic Biologist - Kate Doms Period 4 Nursing – Lorraine Miller .net programming – Scott Kornblatt Period 7 Fashion Retailing – Wendy McDevitt Private Equity Investing – Mike Bailey Author, Judith Donato (center) during Career Period 8 Days 2013 Quick links for Wednesday (March 11, 2015) Room 268 Room 142 Period 2 Entrepreneur – Tom Borger Radio Sales – Paul Blake Period 3 TV Production – Tom Sredenschek Cyber Security – Tom Murphy Period 4 Special Agent (FBI) – Charles Murray Business – Paul Ridder (Tastykake) Period 7 Clinical Social Work – Karen Moon Speakers present in either Large Group Period 8 Graphic Design – Steve Miller Video Production – Mike Fanelle Room 142 or 268. Quick links for Thursday (March 12, 2015) Room 268 Room 142 Period 2 App Development – Phil Reitnour Technology – Scott Snyder Period 3 Accounting – Scott Shreve Music Production – Dan Marino Period 4 Environmental Science – Tony Parisi TV Marketing – Fran McElwee Period 7 Financial Planning – Tom Safford Sports Reporter – Dave Spadaro Students are able to interact with the Period 8 International Business – Seth Morrison Law Enforcement – Jamie Kemm speakers. NO pre-registration for Career Days 2015 – this is NEW. Students attend during “free” period or with approval from their teacher. Open to all students. Information Tables will be set up during all LUNCH periods: March 5, 6 & 9 in the Cafeteria CHS Career Days 2015 speaker biographies are on page 2-8 of this document (alpha by topic). -

URBAN OUTFITTERS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended January 31, 2021 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ________ to ________ Commission File No. 000-22754 URBAN OUTFITTERS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Pennsylvania 23-2003332 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) 5000 South Broad Street, Philadelphia, PA 19112-1495 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (215) 454-5500 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Shares, par value $.0001 per share URBN NASDAQ Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by checkmark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by checkmark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by checkmark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

About Finch Brands

® about finch brands ABOUT US finch brands is a real-world branding agency. Like the finches whose beaks inspired Darwin’s theory of evolution, brands that adapt to the ever-changing environment not only survive, they thrive. We draw our name and inspiration from the forces that shape the natural world to help our clients succeed in the real world. Finch Brands was founded in 1998 by executives instrumental in the ascent of IKEA and David’s Bridal. Their original vision was to create the firm they were never able to find when they were in our clients’ shoes – an end-to-end brand development and management powerhouse that seamlessly delivers breakthrough brand strategy and irrepressibly creative brand design. To accomplish this, we have brought together a team of leaders from brand- first organizations like Campbell Soup Company, NPR, and Urban Outfitters. These experiences make us a better, more instinctive partner – and we put this hard-earned experience to work for clients across categories and all along the growth track. SERVICES our goal is to be the most consequential partner with whom our clients will ever engage. BRAND DEVELOPMENT BRAND MANAGEMENT vision and mission strategic counsel and growth planning brand strategy brand tracking and brand health brand architecture product/service innovation funnel identity (naming, logo, tagline) pricing brand standards/design systems brand extension / elasticity packaging design and POP advertising campaign development and launch internal brand rollout / training marketing planning / demand generation launch planning and execution social media strategy / program management web design and digital strategy MARKET RESEARCH quantitative surveys focus groups in-depth interviews (IDI) ethnography digital bulletin boards virtual communities in-home research store visits and mystery shopping custom methodologies EXECUTIVE TEAM EXECUTIVE DANIEL ERLBAUM CEO A retailer and business builder, Daniel co-founded Finch Brands after serving as an original investor and Vice President at David’s Bridal. -

COMPANY INDEX WEIGHT ACI Worldwide Inc 0.22% AECOM 0.40% AGCO Corp 0.23% AMC Networks Inc.-A 0.09% ASGN Incorporated 0.19% Aaron's Inc

COMPANY INDEX WEIGHT ACI Worldwide Inc 0.22% AECOM 0.40% AGCO Corp 0.23% AMC Networks Inc.-A 0.09% ASGN Incorporated 0.19% Aaron's Inc. 0.21% Acadia Healthcare Company Inc 0.16% Acuity Brands Inc 0.25% Adient Inc. 0.13% Adtalem Global Education Inc 0.10% Affiliated Managers Grp 0.22% Alleghany Corp (NY) 0.63% Allegheny Technologies Inc 0.14% Allete Inc 0.23% Allscript Healthcare Solutions Inc 0.08% Amedisys Inc 0.35% American Campus Communities Inc 0.35% American Eagle Outfitters 0.13% American Financial Group 0.46% Antero Midstream Corp 0.08% Apergy Corp 0.11% AptarGroup Inc 0.39% Arrow Electronics Inc 0.35% Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Inc 0.23% Ashland Global Holdings Inc 0.26% Associated Banc-Corp (IL) 0.18% AutoNation Inc 0.15% Avanos Medical, Inc 0.08% Avis Budget Group Inc 0.13% Avnet Inc 0.20% Axon Enterprise Inc 0.28% BANK OZK 0.18% BJ's Wholesale Club Holdings 0.14% BancorpSouth Inc (MS) 0.15% Bank of Hawaii Corp 0.20% Bed Bath & Beyond Inc 0.08% Belden Inc 0.11% Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc A 0.44% Bio-Techne Corp 0.42% Black Hills Corp 0.28% Blackbaud Inc 0.21% Boston Beer Inc A 0.20% Boyd Gaming Corp 0.14% Brighthouse Financial Inc 0.27% Brinker Intl Inc 0.09% Brixmor Property Group Inc 0.33% Brown & Brown Inc 0.59% Brunswick Corp 0.29% CACI International Inc 0.37% CDK Global Inc 0.34% CIENA Corp 0.36% CIT Group Inc 0.24% CNO Financial Group Inc 0.16% CNX Resources Corp. -

In Re Innocoll Holdings Public : Ltd

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA : : IN RE INNOCOLL HOLDINGS PUBLIC : LTD. CO. SEC. LITIG. : CIVIL ACTION : : No. 17-341 : MEMORANDUM PRATTER, J. SEPTEMBER 5, 2018 The plaintiffs in this securities class action allege that Innocoll Holdings Public Ltd. Co., Chief Executive Officer Anthony Zook, and Chief Medical Officer Dr. Lesley Russell made misleading statements or omissions about XaraColl, a collagen product the pharmaceutical company was developing during the class period. The defendants allegedly made positive statements about the New Drug Application for XaraColl even though they knew, or recklessly failed to know, that XaraColl contained device components that had not yet been tested. The plaintiffs contend that, by making such statements, the defendants misled investors who relied on the positive statements. The plaintiffs present securities fraud claims against all defendants under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5. They also make individual control liability claims against Mr. Zook and Dr. Russell under Section 20(a). The defendants filed a motion to dismiss all the claims under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6). In doing so, they attached to their motion a declaration from the plaintiffs’ confidential witness, which then prompted the plaintiffs to file a motion to convert the motion to dismiss into one for summary judgment. 1 For the reasons outlined in this Memorandum, the Court: (1) denies the motion to convert and, instead, disregards the declaration; and (2) grants the motion to dismiss with leave to amend because the plaintiffs failed to meet the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act’s heightened pleading standard relating to the element of scienter. -

John Kammerer

John G. Kammerer 12 Lambourne Path (856) 340-0253 Sewell, New Jersey 08080-3142 [email protected] (http://www.linkedin.com/in/johnkammerer) POSITIONING STATEMENT: Driven and resourceful financial executive with a proven track record of providing vision, leadership and innovative solutions to meet business objectives. Over 25 years of broad industry experience including high growth enterprises ranging from start-ups to an equity-backed entity. Key Accomplishments Include: • Created reporting submissions & KPI • Developed & implemented ERP strategies • Executed operational restructuring • Implement business processes & governance • Created shared services • Developed risk management strategies • Implementation of SOX-404 controls • Managing credit risk programs • Design medical benefits program with broker • Annual audit & tax coordination/responsibility SEARCH OBJECTIVE: Divisional Vice President of Finance (start-up to multi-billion revenue company) / Operational CFO (start- up to multi-billion revenue company) role in a public or equity-backed company AREAS of EXPERTISE: Organizational Partnership Financial Management Manufacturing Based ERP Systems Development Budgeting / Forecasting Manufacturing Excellence Staff Development & Succession Financial Reporting & Integrity Lean Manufacturing Process Analytics & Improvement Debt Management Six Sigma – Green Belt Cost & Profitability Improvement Internal Controls Cost Accounting Business Partnering Cost & Risk Management Inventory Control TARGETED COMPANIES: • Aramark • Campbell -

Ngai V. Urban Outfitters, Inc., No. 19-Cv-1480

Case 2:19-cv-01480-WB Document 50 Filed 03/29/21 Page 1 of 44 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA PAUL NGAI AND XIAOYAN NGAI, CIVIL ACTION Plaintiff, v. URBAN OUTFITTERS, INC., LORIE A. NO. 19-1480 KERNECKEL, BARBARA ROZASAS, JOHN DOES 1 THROUGH 10 AND ABC CORPORATIONS 1-10, Defendants. MEMORANDUM OPINION Defendants Urban Outfitters, Inc. (“Urban”), Lorie A. Kerneckel, and Barbara Rozsas (collectively, Defendants) move for summary judgment on Paul Ngai (“Plaintiff” or “Ngai”) and Xiaoyan Ngai’s (together, “Plaintiffs”) claims for national origin and age discrimination, retaliation, and hostile work environment in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII), the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA), the Pennsylvania Human Rights Act (PHRA), and the Philadelphia Fair Practices Ordinance (PFPO), aiding and abetting discrimination in violation of the PHRA and PFPO, whistleblower retaliation in violation of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, violation of the Pennsylvania Wage Payment and Collection Law (WPCL), and common law intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED) and loss of consortium.1 In turn, Plaintiffs move for partial summary judgment with respect to Defendants’ affirmative defense that Ngai failed to mitigate damages. For the reasons that follow, Defendants’ motion will be granted in part and denied in part and Plaintiffs’ motion will be denied. 1 Plaintiff abandons his gender-based claims of discrimination, retaliation, and hostile work environment, common law wrongful discharge, and whistleblower retaliation under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in his summary judgment briefing. These claims will therefore be dismissed.