Measuring the Local Economic Impacts of Protected Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bovine Tuberculosis in Elk (Cervus Elaphus Manitobensis) Near Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, from 1992 to 2002

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Michigan Bovine Tuberculosis Bibliography and Wildlife Disease and Zoonotics Database 2003 Bovine Tuberculosis in Elk (Cervus Elaphus Manitobensis) near Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, from 1992 To 2002 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/michbovinetb Part of the Veterinary Medicine Commons "Bovine Tuberculosis in Elk (Cervus Elaphus Manitobensis) near Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, from 1992 To 2002" (2003). Michigan Bovine Tuberculosis Bibliography and Database. 49. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/michbovinetb/49 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Disease and Zoonotics at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Bovine Tuberculosis Bibliography and Database by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CROSS-CANADA DISEASE RAPPORT DES MALADIES REPORT DIAGNOSTIQUÉES AU CANADA Manitoba Bovine tuberculosis in elk (Cervus Elk were first implicated in 1992, when a wild elk shot elaphus manitobensis) near Riding in the vicinity of an infected cattle farm was found to be harboring the disease. Since 1997, an expanded wildlife Mountain National Park, Manitoba, surveillance program has operated under a federal- from 1992 to 2002 provincial partnership of Parks Canada, the Canadian rom 1991 to April 2003, outbreaks of bovine Food Inspection Agency, Manitoba Agriculture and Food, F tuberculosis (TB caused by Mycobacterium and Manitoba Conservation. Animals shot by hunters or bovis) have been found in 11 cattle herds surround- found dead are examined for gross evidence of bovine ing Riding Mountain National Park (RMNP). Located TB and suspicious lesions are submitted for histological in southwestern Manitoba, RMNP and the surround- and cultural confirmation. -

Visitor Guide

VISITOR GUIDE 2017 Contents 3 Celebrate Canada 150 4 Welcome 5 Calendar of events 6 The Franklin Expedition 6 Artists in Residence 7 Visitor Centre 8-9 Guided experiences 10 Indigenous People of Riding Mountain 11 Bison and Wildlife 12-13 Camping 14-15 Trails 16-17 Riding Mountain National Park map 18 Wasagaming map 19 Clear Lake map 20-21 Welcome to Wasagaming 22-23 History of Riding Mountain 24 Clear Lake Country 25-27 The Shops at Clear Lake 28 Friends of Riding Mountain National Park 29 Photo Contest 30-33 Visitor Information 34 Winter in Riding Mountain 35 Contact Information Discover and Xplore the park Get your Xplorer booklet at the Visitor Centre and begin your journey through Riding Mountain. Best suited for 6 to 11-year-olds. 2 RidingNP RidingNP Parks Canada Discovery Pass The Discovery Pass provides unlimited opportunities to enjoy over 100 National Parks, National Historic Sites, and National Marine Conservation Areas across Canada. Parks Canada is happy to offer free admission for all visitors to all places operated by Parks Canada in 2017 to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Confederation. For more information regarding the Parks Canada Discovery Pass, please visit pc.gc.ca/eng/ar-sr/lpac-ppri/ced-ndp.aspx. Join the Celebration with Parks Canada! 2017 marks the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation and we invite you to celebrate with Parks Canada! Take advantage of free admission to national parks, national historic sites and national marine conservation areas for the entire year. Get curious about Canada’s unique natural treasures, hear stories about Indigenous cultures, learn to camp and paddle and celebrate the centennial of Canada’s national historic sites with us. -

THE NATIONAL PARK 87 15 CRAWFORD PARK 91 16 CLEAR LAKE THEN and NOW 94 17 SNAPPING up LAKESIDE LOTS 101 18 RIDING MOUNTAIN POTPOURRI 103 Introduction

i= I e:iii!: When Walter Dinsdale, MP for Brandon EMMA RINGSTROM, who was born on her Souris, learned that a book was being pre parents' homestead near Weyburn, Sask., pared on tj1e Riding Mountain, he wrote, "It moved with her husband to Dauphin, Man.,. gives me great pleasure to congratulate in 1944. Mr. Ringstrom was a grain buyer for Emma H. Ringstrom and the Riding Moun National Grain Co. She later became an tain Historical Society on the presentation associate of Helen Marsh, editor and subse of this excellent history ... quently owner and publisher of the Dauphin "As a young lad, I was present at the offi Herald. cial opening--my father, George Dinsdale, At one time Mrs. Ringstrom owned and attended in his capacity as MLA for Bran operated the Wasagaming Lodge at Clear don. When I married Lenore Gusdal in Lake and did some r~porting fo, the Dauphin 1947, I discovered that her father, L. B. Gus Herald, the Wirinipeg Free Press, the Min dal, had taken out the first leasehold long nedosa Tribune and the Brandon Sun. before Riding Mountain became a national She collaborated with Helen Marsh on a park. Many of her relatives were among the book on Dauphin and district. Scandinavian craftsmen who left a unique She has been active in community affairs, legacy in log buildings, stone work and furni the school board, and the area agricultural ture." society. Later, Mr. Dinsdale was instrumental in Mrs. Ringstrom is the mother of five chil introducing a zoning policy "to preserve the dren. -

BUSINESS DIRECTORY (Businesses in Immediate Vicinity)

BUSINESS DIRECTORY (Businesses in immediate vicinity) Riding Mountain National Park – (RMNP) Accommodations Arrowhead Chalets (Mooswa) Wasagaming 204-848-2533 Aspen Ridge Resort Wasagaming 204-848-2511 Boulevard Motor Hotel Dauphin 204-638-4410 Buffalo Resort Ltd. Wasagaming 204-848-2404 Canway Inn & Suites Dauphin 204-638-5102 Clear Lake Lodge Wasagaming 204-848-2345 / 866-355-4676 Cottages at Clear Lake Wasagaming 204-848-8489 / 888-848-2524 Dauphin Community Inn Dauphin 204-638-4311 Dauphin Inn Express Motel Dauphin 204-638-4430 Elkhorn Resort (year round) Onanole 204-848-2802 / 866-355-4676 Evergreen B&B Onanole 204-848-2681 Highland Motel Dauphin 204-638-5100 Idylwylde Bungalows Wasagaming 204-848-2383 Lakeside Airie B&B (Compty) Ditch Lake 204-848-2010 Lakeside Resort Ditch Lake 204-848-7311 Manigaming Resort Wasagaming 204-848-2459 McTavish’s Wasagaming Lodge Wasagaming 204-848-7366 / 888-933-6233 Millenianne Eden Garden B&B (year round) Onanole 204-848-8428 Mooswa Resort Wasagaming 204-848-2533 / 866-848-2533 The New Chalet Wasagaming 204-848-2892 The Nordic Inn (year round) Erickson 204-636-2601 Park Vista Chalet Onanole 204-888-1179 Prairie Mountain Inn Dauphin 204-638-4233 Riding Mountain Guest Ranch Lake Audy 204-848-2265 Smokey Hollow Resort (year round) Onanole 204-848-2600 Southgate Motor Inn & Hotel (year round) Onanole 204-848-2158 Stone’s Throw B&B Suites Onanole 204-848-2891 Super 8 Motel Dauphin 204-639-0800 Thunderbird Bungalows Wasagaming 204-848-2521 Towers Hotel Dauphin 204-638-4321 Banks Dauphin Plains Credit -

Riding Mountain National Park Environmental Impact Analysis

September 2015 Manitoba Hydro V38R/Line 81 Riding Mountain National Park Environmental Impact Analysis Submitted to: Manitoba Hydro Licensing & Environmental Assessment Department 820 Taylor Ave (3) Winnipeg, Manitoba R3M 3T1 Prepared by: M. Forster Enterprises PO Box 931 Teulon, Manitoba R0C 3B0 Joro Consultants Inc. PO Box 23 Clandeboye, Manitoba AAE Tech Services Inc. PO Box 1064 LaSalle, Manitoba R0G 1B0 Dillon Consulting Ltd. 1558 Wilson Place Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 0Y4 Manitoba Hydro V38R/Line 81 Riding Mountain National Park Environmental Impact Analysis September 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report documents an Environmental Impact Analysis for activities associated with two existing Manitoba Hydro transmission lines that cross through a section of Riding Mountain National Park. It is submitted in response to Section 67 of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act 2012 (CEAA 2012) as it is being carried out on federal lands. As Parks Canada is the authority administering these lands, it is submitted to Parks Canada following the Guide to Parks Canada Environmental Impact Analysis under CEAA 2012. The 230 kV V38R and the 115 kV Line 81 transmission lines were constructed in 1964 in a common 34 kilometre long Right-of-Way that enters the park at its northern boundary and continues south through the park to its southern boundary. For almost 50 years the transmission lines and Right-of-Way have been operated and maintained by Manitoba Hydro to provide service to customers outside of the park area, through collaboration with Parks Canada and the Province of Manitoba. The process of collaboration has been undertaken to facilitate mutually agreeable approaches and practices that allow Manitoba Hydro to operate and maintain the transmission lines and Right-of-Way in a manner that protects the environment and the ecological integrity of the park while maintaining a safe and reliable electrical system. -

Riding Mountain National Park of Canada

Manitoba Star Attraction Riding Mountain National Park of Canada VISITOR GUIDE 2010 Contents Welcome Riding Mountain National Park – You’re invited to 2010 Events – 3 Interpretive Experiences – 4 Real. Inspiring. Camping – 7 and above all fun experiences – all in a beautiful, Geocaching – 10 natural setting. Townsite – 11 Bison Watch – 12 Are you looking for warm summer sun? Do you want Trails – 13 to “rough it” in the wilderness? Are you interested in learning about our natural and cultural heritage? Park History – 15 Perhaps you want to spend time enjoying our crisp, First Nations – 19 clear Manitoba winter? Whatever experiences you Licensed Guides – 22 DUHORRNLQJIRU\RXZLOO¿QGVRPHWKLQJIRUHYHU\RQH RMNP Map (Center) – 23 here at Riding Mountain National Park. Wasagaming Map – 25 Our national parks and national historic sites are an Clear Lake Map – 26 important part of what makes Canada such a great Ecosystem Management – 27 place to live. You will discover many high quality recreational activities and special events to entertain Resource Conservation Projects – 29 and thrill you. You can also uncover the secrets of Animal Look-alikes – 31 this protected place that preserves important and Activities– Something for Everyone – 33 often unique species of plants and animals, as well as Mainitoba Escarpment – 36 VLJQL¿FDQWFXOWXUDODQGKLVWRULFGHWDLOVIURPRXUSDVW Need to Know – 37 Along with all of our partners and neighbours in the Our Neighbors – 41 Parkland region, let us be your starting point for ex- ploring all that the area has to offer…we’re sure you’ll ¿QGVRPHWKLQJKHUHWRWUHDVXUH Also... Cheryl Penny Keep your eyes peeled for Superintendent “Things To Do?” throughout the Visitor’s Guide for adventurous ideas! Things to do? There are 23 in total, FDQ\RX¿QGWKHPDOO" 1 Visitor Centre The “meeting place” in Wasagaming is Many fascinating learning experiences begin at the the Visitor Centre, a remarkable Federal Visitor Centre where you can sign up for guided hike experiences and other outdoor adventures. -

State of the Community Report Wasagaming 2 November, 2006 Community Plan Are Followed

State of the Community Report Wasagaming An assessment of the framework for managing land-use and development in Wasagaming, Manitoba Riding Mountain National Park of Canada November, 2006 Table of Contents Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………………….2 State of the Community Report……………………………………………………………………...6 Wasagaming, Riding Mountain National Park……………………………………………………..6 1.0 Context…………………………………………………………………………………………….6 2.0 Indicators and Measures…………………………………………………………………………8 3.0 State of the Community………………………………………………………………………….9 3.1 No Net Negative Environmental Impact & Environmental Stewardship.....................................9 3.1.1 Aquatic ecosystems .........................................................................................................9 3.1.2 Terrestrial Ecosystems (Vegetation) ...............................................................................12 3.1.3 Terrestrial Ecosystems (Wildlife) ....................................................................................12 3.1.4 Solid Waste Diversion ....................................................................................................13 3.1.5 Contaminated Sites .........................................................................................................13 3.2 Leadership in Heritage Conservation .........................................................................................13 3.2.1 Built Heritage ................................................................................................................13 -

2020 TRAVEL MANITOBA INSPIRATION GUIDE on the Bald Hill at Riding Mountain National Park COVER Shared with #Exploremb by @Clearlakecountry

2020 TRAVEL MANITOBA INSPIRATION GUIDE ON THE Bald Hill at Riding Mountain National Park COVER Shared with #exploremb by @clearlakecountry. Photo by Austin MacKay. TABLE OF CONTENTS discover the Home of 2 4 29 MANITOBA REGIONS OUTDOOR EXPLORATIONS REGIONAL ROAD TRIPS Each of Manitoba’s seven tourism regions has a Camping, hiking, paddling, fishing, snowmobiling Manitoba’s regional cities and towns are destinations distinct personality – easily discovered through its and more – explore Manitoba’s forests, lakes, beaches worth discovering. Find interesting art and history, share of Manitoba’s Star Attractions. and parks. food and farms and, of course, friendly people full WinteR interesting stories. 59 81 WINNIPEG ADVENTURES FESTIVALS & EVENTS 89 VISITOR Manitoba’s capital city is the biggest urban centre Our lively gatherings celebrate everything from our INFORMATION CENTRES in the Canadian Prairies. Discover the culture, love of music to our mosaic of cultures. Come dance, architecture and food in this city that continues eat and be entertained all year long while truly 90 ABOUT MANITOBA to surprise visitors. getting to know Manitoba. 81 PACKAGES & DEALS Call this toll-free number: 1-800-665-0040 (or 204-927-7838 in Winnipeg) for free United in Celebration literature (from Travel Manitoba and private suppliers), information and personalized – travel counselling, or write: Travel Manitoba, 21 Forks Market Road Winnipeg, Unis dans la fête Manitoba R3C 4T7 Free Distribution/Printed in Canada Si vous voulez obtenir des publications gratuites (provenant de Voyage Manitoba et de compagnies privées), des renseignements et 2020 marks 150 years since Manitoba became Canada’s fifth des conseils touristiques personalisés, veuillez appeler le numéro sans frais indiqué ci-dessus 1-800-665-0040 (ou le 204-927-7838, CLEAR LAKE COUNTRY province. -

Surficial Geology of the Riding Mountain Map Sheet (NTS 62K)

YZ10 R 29 W R 28 W R 27 W R 26 W R 25 W R 24 W R 23 W R 22 W R 21 W R 20 W R 19 W 102° Dropmore YZ83 100° 300 000 325 000 ! 350 000 375 000 400 000 425 000 0 0 0 51° 0 51° SURFICIAL GEOLOGY COMPILATION MAP SERIES 5 6 5 Tp 23 The Surficial Geology Compilation Map Series (SGCMS) addresses an increasing demand for Tp 23 0 consistent surficial geology information for applications such as groundwater protection, 0 0 0 industrial mineral management, protected lands, basic research, mineral exploration, 5 6 5 engineering, and environmental assessment. The SGCMS will provide province-wide coverage Inglis at scales of 1:500 000, 1:250 000 and a final compilation at 1:1 000 000. ! Shellmouth ! Edwards The unit polygons were digitized from paper maps originally published by the Geological Survey of Canada and Manitoba Geological Survey (MGS). In several areas, digital polygons derived from soils mapping were used to fill gaps in the geological mapping. The 1:250 000 Tp 22 L Tp 22 scale maps provide a bibliography for the original geological mapping. 10 YZ Edge-matching of adjoining 1:250 000 scale map sheets is based on data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Digital Elevation Model (SRTM DEM1) as interpreted by the MGS. Gunn Other polygon inconsistencies were modified in a similar manner. Geology (colour) is draped Cracknell over a shaded topographic relief map (grey tones) derived from the SRTM DEM. ! Lake 1 United States Geological Survey 2002: Shuttle radar topography mission, digital elevation model, Manitoba; United YZ83 States Geological Survey, URL <ftp://edcsgs9.cr.usgs.gov/pub/data/srtm/>, portions of files N48W88W.hgt.zip through N60W102.hgt.zip, 1.5 Mb (variable), 90 m cell, zipped hgt format [Mar 2003]. -

Manitoba Visitor Guide 2021

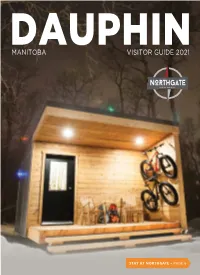

DAUPHIN MANITOBA VISITOR GUIDE 2021 STAY AT NORTHGATE – PAGE 6 CONTENTS Welcome to Dauphin 3 Dauphin Memorial Community COMMUNITY 66 Economic Development Dauphin 4 Centre Grounds 36 Dauphin Art Group 67 Important Contacts 4 Vermillion Sportsplex 37 Vermillion Park 38 Dauphin Pottery & Ceramics Club 67 ADVENTURES 5 Fort Dauphin Museum 40 Parkland Women’s Choir 68 Northgate Dauphin Trail System 5 Trembowla Cross of Freedom 42 Keystone Chorus 68 Selo Ukraina 43 Stay at Northgate 6 Theatre Amisk 69 Trail Map 8 CNoR Station & Dauphin Rail Museum 44 Dauphin’s Community Band 69 Ride the Region 9 The Historic Ukrainian Catholic Immigrant Services 70 Hike & Bike 8 Church of the Resurrection 45 Road Tripping 10 Dauphin Multi-Purpose Seniors Centre 71 Parks 46 Dauphin Lake 12 Dauphin Public Library 72 Skate Park 48 Parkland Paddling Club 14 Dauphin Friendship Centre 73 Family-Friendly Paddling 15 MAIN EVENTS 50 Dauphin & District Blazing Trails 16 Dauphin’s Countryfest 51 Chamber of Commerce 74 Quiet Camping 17 Canada’s National Ukrainian Festival 52 The Hub 76 Golf 18 MS Ride 54 Volunteering in Dauphin 77 Statues of Dauphin 20 Threshing Day 54 Watchable Wildlife 22 Race RMNP 55 SERVICES 79 Hunting 24 Manitoba Mudrun 56 Service Listings 79 Angling 26 Color Blast Fun Run 57 Secord Corn Maze 28 Dauphin Agricultural Fair 58 Traveling to Dauphin 83 North Mountain Adventures 29 Dauphin Chamber of Accommodations 85 Commerce Street Fair 60 Custom Group Experiences 86 PLACES 30 Rotary Lobsterfest Kitchen Party 61 Hosting Events in Dauphin 87 Watson Art Centre (WAC) 30 Dauphin’s Culture Days 62 Dauphin’s Bed & Breakfast 87 Parkland Recreation Complex 32 Hockey Night in Dauphin 63 Credit Union Place (CUP) 34 Christmas in Dauphin 64 City of Dauphin Map 88 Countryfest Community Cinema 35 Louis Riel Day at Fort Dauphin 65 RM of Dauphin Map 90 Information in this guide is subject to change at any time. -

Field Trip: Ice-Shoved Hills and Related Glaciotectonic Features

D. J. Wiseman and R. A. McGinn Field trip: Ice-shoved hills and related glaciotectonic features Field trip: Ice-shoved hills and related glaciotectonic fea- tures in the Glacial Lake Proven Basin Dion J. Wiseman Department of Geography, Brandon University Roderick A. McGinn Department of Geography, Brandon University Introduction relative relief) and large composite ridges (>100 m relative relief and arcuate in form). Large composite thrust ridges in North Constructional glaciotectonic landforms include a variety of Dakota are described by (Moran et al. 1980). The Brandon Hills hills, ridges and plains composed wholly or partly of soft bed- in southwestern Manitoba are an example of a small composite rock or drift masses deformed or dislocated by glacier-ice move- linear ridge (Welsted and Young 1980; Aber 1989). Cupola- ment (Aber 1985). Aber (1989) classified constructional glacio- hills are glaciotectonic hills lacking a hill-hole relationship and tectonic landforms into five types, comprising hill-hole pairs, or transverse ridge morphology (Bluemle and Clayton 1984). large composite ridges, small composite ridges, cupola-hills, They have a dome-like morphology, circular to oval to elongated and flat lying mega blocks. These classes represent the ideal oval shape, and are composed of deformed floes of Quaternary generic types within a continuum of glaciotectonic landforms. sediments or older bedrock overlain by a thin carapace of till Intermediate, transitional, and mixed features also can be de- (Benn and Evans 2010). Finally, megablocks or rafts are dislo- scribed. cated slabs of rock and unconsolidated material transported from Benn and Evans (2010) employ Aber’s 1989 classification their original position by glacial action (Benn and Evans 2010). -

The Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve

Christoph Stadel and Don Huisman The Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve The Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve (RMBR): Challenges, opportunities, and management issues at the southern fringe of Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba Christoph Stadel University of Salzburg, Austria Don Huisman Erickson, Manitoba Key Messages • Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve (RMBR) is one of three biosphere reserves in the Canadian prairies. • Multiple interactions take place between Riding Mountain National Park, the adjacent municipalities, and First Nation reserves. • Projects and activities pose challenges that for successful resolution require cooperation among RMBR stakeholders. Riding Mountain Biosphere Reserve (RMBR) was founded in 1986, 53 years after the establishment of Riding Mountain National Park (RMNP). Currently the RMBR is one of 18 biosphere reserves in Canada, three of which are located in the Prairie region. The reserve has a total area of approximately 13,310 km2 comprising the RMNP core area measuring 2,700 km2, a buffer zone of 268 km2, and a transition zone or cooperation area of 10,342 km2. Fourteen municipalities and four First Nation reserves are located within the transition zone. Three of the reserves (Rolling River, Keeseekoowenin, and Waywayseecappo) are located in the southern part of the RMBR. This paper focuses on the complex ecological, demographic, cultural, socio-economic, and political-administrative framework and relationships between RMNP, the municipalities, and the First Nation reserves. ‘Baskets’ of complementarities, mutual opportunities and benefits contrast with multiple challenges, diverging interests, and potential sources of conflict. Recently, enhanced communication, closer interactions, and joint projects have characterized relationships, at least in some areas between the National Park, and some of the municipalities and First Nation reserves.