Dowson V. the Queen H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left During the Long Sixties

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-13-2019 1:00 PM 'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties David G. Blocker The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Fleming, Keith The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © David G. Blocker 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons Recommended Citation Blocker, David G., "'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6554. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6554 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Abstract The Sixties were time of conflict and change in Canada and beyond. Radical social movements and countercultures challenged the conservatism of the preceding decade, rejected traditional forms of politics, and demanded an alternative based on the principles of social justice, individual freedom and an end to oppression on all fronts. Yet in Canada a unique political movement emerged which embraced these principles but proposed that New Left social movements – the student and anti-war movements, the women’s liberation movement and Canadian nationalists – could bring about radical political change not only through street protests and sit-ins, but also through participation in electoral politics. -

Entryism in Theory, in Practice, and in Crisis: the Trotskyist Experience in New Brunswick, 1969-1973 by Patrick Webber

Left History 14_1-b - Quark Final 12/4/09 1:06 PM Page 33 Entryism in Theory, in Practice, and in Crisis 33 Entryism in Theory, in Practice, and in Crisis: The Trotskyist Experience in New Brunswick, 1969-1973 By Patrick Webber Since the emergence of a distinct Trotskyist faction within the Communist move- ment by the mid-1930s, the policy of entryism has been a favourite tactic among Trotskyists, particularly in the West. Entryism would be a major factor in the cre- ation of the New Brunswick Waffle in 1970, the provincial wing of the Waffle movement that had emerged in the New Democratic Party (NDP) the previous year.1 Conflicting interpretations over the implementation of entryist theory, how- ever, would also help split and destroy the NB Waffle by the end of 1971 and inflict lethal damage on the nascent Trotskyist movement in New Brunswick. The ultimate impact of the crisis in entryism provoked by the Trotskyist experience in New Brunswick in 1970-71 was to raise major doubts about the theory and prac- tice of entryism among Canadian Trotskyists, culminating in the fracturing of the League for Socialist Action (LSA), Canada’s pre-eminent Trotskyist organization. The events that surrounded the NB Waffle therefore proved to be a turning point in the history of Trotskyist strategy in Canada. The strategy of entryism was first known as the “French Turn,” as it was first in France where Trotskyists debated and engaged in entryism. In June 1934, Trotsky himself declared that his followers in that country should seek to enter the French Socialist Party, a shift in policy that was provoked by the formation of a United Front. -

Finding Aid No. 2360 / Instrument De Recherche No 2360

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA/BIBLIOTHÈQUE ET ARCHIVES CANADA Canadian Archives Direction des archives Branch canadiennes Finding Aid No. 2360 / Instrument de recherche no 2360 Prepared in 2004 by John Bell of the Préparé en 2004 par John Bell de la Political Archives Section Section des archives politique. II TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................................................................iv Series 1: Internal bulletins, 1935-1975 ....................................................................................1 Series 2: Socialist Workers Party internal information bulletins, 1935-1975 .......................14 Series 3: Socialist Workers Party discussion bulletins, 1934-1990.......................................19 Series 4: International bulletins and documents, 1934-1994 ................................................28 Series 5: Socialist League / Forward Group, 1973-1993 ......................................................36 Series 6: Forward files, 1974-2002........................................................................................46 Series 7: Young Socialist / Ligue des jeunes socialistes, 1960-1975 ....................................46 Series 8: Ross Dowson speech and other notes, 1940-1989..................................................52 Series 9: NDP Socialist Caucus and Left Caucus, 1960-1995...............................................56 Series 10: Gord Doctorow files, 1965-1986 ..........................................................................64 -

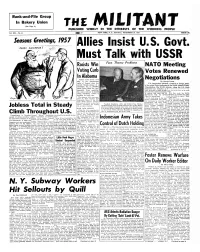

NY Subway Workers Hit Sellouts by Quill

Rank-and-File Group In Bakery Union (See Page 4) t h e MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Vol. X X I - No. 51 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, DECEMBER 23, 1957 P R IC E 10c Seasons Greetings, 1957 Allies Insist U.S. Govt. Must Talk with USSR Racists Win NATO Meeting Voting Curb Votes Renewed In Alabama Alabama racists struck a new Negotiations blaw at the Constitutional By George Lavan rights of Negroes when they U.S. imperialism suffered a setback in foreign policy jammed through passage of a at the recent Paris conference of the North Atlantic Treaty referendum, Dec. 17, abolishing Organization. The NATO nations, whom the U.S. State Macoiii County which has a pre Department has heretofore al- &- dominantly Negro population. ways been able to cajole or bull and the Soviet bloc on a world The county will now be divided doze into line, almost unanimous scale. among neighboring counties to ly insisted that some sort of Why then were the NATO negotiations with the Soviet politicians so insistent that talks fragment its Negro vote. Union be entered into. with the USSR be begun? What The measure, which was spon In the week .prior to the con is their aim ? sored by State Senator Sam ference Washington had cavali There has been a tremendous Englehardt, leader of the Ala erly dismissed, as unworthy of rise in anti-war feeling among bama White Citizens Councils, consideration and mere “mis the masses of all countries since w ill next go before a state leg President Eisenhower (left) and British Prime Minister chief-making,” the letters of sputnik announced the age of islative committee for ironing missile warfare. -

“A Challenge and a Danger” Canada and the Cuban Missile Crisis

“A Challenge and A Danger” Canada and the Cuban Missile Crisis By Caralee Daigle Hau A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in History in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada December 2011 Copyright © Caralee Daigle Hau 2011 Abstract President John F. Kennedy’s announcement, on Monday 22 October 1962, that there were offensive missiles on the island of Cuba began the public phase of what would be remembered as the Cuban missile crisis. This Cold War crisis had ramifications in many other countries than just the Soviet Union and the United States. Due to the danger involved in this nuclear confrontation, the entire globe was threatened. If either side lost control of negotiations, an atomic war could have broken out which would have decimated the planet. As the direct northern neighbors of the United States and partners in continental defence, Canadians experienced and understood the Cuban missile crisis in the context of larger issues. In many ways, Canadian and American reactions to the crisis were similar. Many citizens stocked up their pantries, read the newspapers, protested, or worried that the politicians would make a mistake and set off a war. However, this dissertation argues that English Canadians experienced the crisis on another level as well. In public debate and print sources, many debated what the crisis meant for Canadian-Cuban relations, Canadian-American relations and Canada’s place in the world. Examining these print and archival sources, this dissertation analyzes the contour of public debate during the crisis, uniting that debate with the actions of politicians. -

Steel Production Plunges to Lowest Since the Thirties

The 1 9 6 0 Socialist Vote See Page 4 th e MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Vol. XXIV — No. 47 NEW YORK. N. Y., MONDAY, DECEMBER 26. 1960 P ric e 10c Auto Group Calls “Algeria Is Algerian!" Steel Production For "30-for-40" Plunges to Lowest Urges Nationwide Conference Of AFL-CIO in Fight for Jobs Since the Thirties DETROIT, Dec. 19 — The immediate calling of a national conference of all AFL-CIO unions to fight for Corporations Decide to Stop the 30-hour week at 40-hours pay, and to formulate a united legislative program for Bares Truth Announcing Rate of Capacity the new Congress, was proposed Socialist Slate here last week by the National About Crisis By Tom Kerry Committee for Democratic Ac Dec. 22 — It is estimated that the rate of steel produc tion in the United Automobile Wins Gains in Workers union, . In Caribbean tion next week w ill be at 40 per cent of capacity or lower. The proposal was made in the Remember how Eisenhower Next week’s rate, says the Dec. 20, New York Times, “may form of a letter by NCFDA be the lowest for a nonstrike period since the depression Toronto Race Chairman Eugene Hoffman to ordered the U.S. fleet into the Walter Reuther and the UAW Caribbean in November to “pro days of the Nineteen Thirties.” The Toronto municipal elec international executive board, tect” the dictators in Nicaragua The hoped for rise in steel demand by the auto industry tion Dec. 5 was the most fruitful which was holding a meeting in and Guatemala from being over one for socialists in a decade. -

Canadian Trotskyism in the 1960'S

Canadian Trotskyism in the 1960’s 1 Introduction Canada is a remarkably stable country. Its institutions and traditions are derived primarily from England and from pre-revolutionary France. Admit- tedly there have been revolutions and armed conflict in Canadian history for example in 1837 and in the Riel rebellion, but these have been the ex- ception and not the rule. Usually consensus, compromise, and evolutionary change have been the norm. For one thing, at the time of Confederation the elites well understood that the alternative to compromise was American annexation. So English and French, Protestant and Catholic, broke bread, made agreements, and honoured them, however they may have felt about each other in private. And yet this is a document about a revolutionary movement in Canada. Revolutions are based on issues. What are the issues in Canadian politics today? I suggest that they can be presented as questions grouped as follows: Environment and health. - will Canada, or even mankind, be able to reply to future environmental challenges or do we face extinction? - can the medical system be made functional? Economics. 1 - can Canada overcome the unfairness in its economic relationship with the United States? - will Canadians continue to be prosperous in an evolving world? In par- ticular, will our children have something approaching the opportunities that were available to the post-war generation? Foreign and domestic policy. - what is one doing in Afghanistan, where is it going and how will it end? - can the national question in Qu´ebec be settled definitively and harmo- niously? - can the aboriginal peoples of Canada find a mode of life that is dignified and replies to their specificity? Justice and culture. -

"Greetings of Ross Dowson to Congress of the International

GREETINGS OF ROSS DOWSON TO CONGRESS OF THE INTERNATIONAL MARXIST GROUP [BRITAIN] (June 19- 20, 1971) It is both a pleasure and an honour to be able to extend the warmest greetings of the League for Socialist Action/La Ligue Socialiste Ouvrière and the Young Socialists/Ligue des Jeunes Socialistes, (the LJS being) the revolutionary socialist youth movement, independent of but in political solidarity with the LSA/LSO, Canadian section of the Fourth International, to this congress of the International Marxist Group, British section of the Fourth International. By rights this greeting should be delivered by and in the spirit of a revolutionist considerably younger than myself and by a woman – because that is where the most profound radicalisation is taking place in Canada and that is who is fusing itself to, “taking over” the Trotskyist movement which this year is celebrating 50 years of unbroken struggle to build the revolutionary vanguard proletarian party in Canada. You should know that the first Trotskyist in the Americas was the Canadian Maurice Spector who continued in 1925-26 under the banner of Trotsky what he and Jack MacDonald, founding secretary of the Canadian Communist Party, commenced under the banner of Lenin in 1921 – and that the Canadian Trotskyists were one of the five groups who first answered Trotsky’s call for a new, a Fourth International. The Canadian Trotskyists are playing the leading role in Bolshevising the radicalization that Canada’s youth, like their contemporaries across the globe, are undergoing. The Canadian Trotskyists are already in a highly favorable position to establish a continuing leadership of this radicalization process. -

Ernest Tate on Cuba

Tate — 1 (What follows is chapter fifteen from volume one of Ernest Tate’s memoir, “Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s and 1960s”, published by Resistance Books, London. In this chapter, using archival sources, he describes in detail how a small group of Canadian revolutionary socialists in the Socialist Educational League, S.E.L., later to become the League for Socialist Action, L.S.A., of which he was a leader, organized in 1960 to defend the early Cuban Revolution against a right-wing propaganda offensive inspired by American imperialism, designed to quarantine it from the Canadian people. Their campaign in defense of Cuba, he writes, was one of the most successful of its kind in the English-speaking world.) Verne Olson and the Cuban Revolution The Cuban Revolution, I have to admit, took our group by surprise. Sometimes, as I’ve discovered, even revolutionaries can be slow in getting off the mark when it comes to recognizing the real deal. I don’t remember us paying much attention to Cuba in the years before 1959, because in such matters we tended to take our lead from the S.W.P. There was not much in The Militant at first, as far as I can recall, and only an occasional item in the Toronto papers. Fidel Castro had been in Montreal in 1957 – and would return as Cuban Premier in 1959 -- but that hadn’t registered with us much but our interest, of course, was piqued with the appearance of Fidel Castro on television when Herbert Mathews, an editor of the New York Times, interviewed him in the Sierra Maestra mountains and we became aware for the first time of the strength of the guerilla struggle against the Batista dictatorship. -

THIS IS IMPORTANT! : Mitch Podolak, the Revolutionary Establishment, and the Founding of the Winnipeg Folk Festival

THIS IS IMPORTANT! : Mitch Podolak, The Revolutionary Establishment, and the Founding of the Winnipeg Folk Festival. By Michael MacDonald, B.A., School of Canadian Studies, Carleton University, Ottawa. [August 2006] A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Canadian Studies Ottawa, Ontario August 1st, 2006 © 2006, Michael MacDonald Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-18282-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-18282-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

CP Heads in NY Back Big Business Candidates

CP Heads in N. Y. Back Big Business Candidates & Openly Oppose Independent Socialist Votes THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE By Herman Chauka i , A policy statement on the New York elections by Ben Vol. XXI ■ No. 45 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 1957 P R IC E 10c Pavis and George Blake Charney, co-chairmen of the New York State Communist Party was published in the Worker Nov. 3. I t aligns the Comm unist-3------------------------------------------------------- Party with the cold-war, red- 9 2 5 V O T E S baiting union bureaucrats of the Liberal Party in support of Tammany’s candidate, Mayor Wagner. The main fire of the statement is directed against the “Buy Less” -- Eisenhower’s Socialist W orkers Party whose candidates campaigned vigorous ly to popularize the need for a labor party and a labor admin istration and to spread the mes sage of socialism. UNITED DRIVE Answer on Rocketing Prices Davis and Charney are spokes men for the Foster and Gates wing of the OP leadership. Their A Husky in Space statement represents a united ef fo rt by the UP tops to throttle Will Nikita Khrushchev Callously Tells People an apparently growing rank-and- file opposition 10 the party's "co alition” line of supporting cap italist candidates endorsed by Become Another Stalin? To Resign Themselves to the labor bureaucracy. (The JOYCE COWLEY, Socialist statement takes issue w ith “the By George Lavan Workers Party candidate for argument fo r abstention in out New York M ayor polled 13,915 NOV.