New Juilliard Ensemble Behind Every Juilliard Artist Is All of Juilliard —Including You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

Keeping Faith: Michael Hamburger's Translations of Paul Celan's Poetry

10.3726/82039_63 Keeping Faith: Michael Hamburger’s translations of Paul Celan’s poetry Von Charlotte Ryland, Oxford In a copy of his volume Die Niemandsrose (1963) given by Paul Celan to his English translator Michael Hamburger, Celan inscribed the words ‘ganz und gar nicht hermetisch’. As Hamburger explains in his edition of Celan transla- tions, this negation of hermeticism would seem to relate to Celan’s conviction, held until his death, that Hamburger had been the anonymous author of a review of Atemwende (1967) in the Times Literary Supplement, in which that poetry had been described as ‘hermetic’.1 This misunderstanding, which caused a schism between Celan and Hamburger that was never fully healed during Celan’s lifetime, has two implications for a consideration of Hamburger’s engagement with Celan’s poetry. On the one hand, according to Hamburger, it put a stop to any fruitful discussions about Celan’s poetry that Hamburger and Celan might have had during those final years of Celan’s life; discussions which might, writes Hamburger, have given him ‘pointers’ as to the ‘primary sense’ of some of the poem’s more obscure terms and allusions.2 On the other hand, it casts a certain light over all of Hamburger’s translations of Celan’s poems: imputing to them an urge to give the lie to that term ‘hermetic’, by rendering Celan’s poems accessible. Hamburger’s translations are therefore not Nachdichtungen, ‘free adaptations’ that lift off from the original poem’s ground; yet neither do they remain so close to the original text as to become attempts at wholly literal renderings, providing notes and glosses where the ‘primary sense’ of an image or term is elusive.3 Rather, Hamburger realised that to write after Celan meant to retain the same relationship between the reader and the text; and therefore to reproduce the complexity and ambiguity that is constitutive of Celan’s verses. -

All Strings Considered a Subjective List of Classical Works

All Strings Considered A Subjective List of Classical Works & Recordings All Recordings are available from the Lake Oswego Public Library These are my faves, your mileage may vary. Bill Baars, Director Composer / Title Performer(s) Comments Middle Ages and Renaissance Sequentia We carry a lot of plainsong and chant; HILDEGARD OF BINGEN recordings by the Anonymous 4 are also Antiphons highly recommended. Various, Renaissance vocal and King’s Consort, Folger Consort instrumental collections. or Baltimore Consort Baroque Era Biondi/Europa Galante or Vivaldi wrote several hundred concerti; try VIVALDI Loveday/Marriner. the concerti for multiple instruments, and The Four Seasons the Mandolin concerti. Also, Corelli's op. 6 and Tartini (my fave is his op.96). HANDEL Asch/Scholars Baroque For more Baroque vocal, Bach’s cantatas - Messiah Ensemble, Shaw/Atlanta start with 80 & 140, and his Bach B Minor Symphony Orch. or Mass with John Gardiner conducting. And for Jacobs/Freiberg Baroque fun, Bach's “Coffee” cantata. orch. HANDEL Lamon/Tafelmusik For an encore, Handel's “Music for the Royal Water Music Suites Fireworks.” J.S. BACH Akademie für Alte Musik Also, the Suites for Orchestra; the Violin and Brandenburg Concertos Berlin or Koopman, Pinnock, Harpsicord Concerti are delightful, too. or Tafelmusik J.S. BACH Walter Gerwig More lute - anything by Paul O'Dette, Ronn Works for Lute McFarlane & Jakob Lindberg. Also interesting, the Lute-Harpsichord. J.S. BACH Bylsma on period cellos, Cello Suites Fournier on a modern instrument; Casals' recording was the standard Classical Era DuPre/Barenboim/ECO & HAYDN Barbirolli/LSO Cello Concerti HAYDN Fischer, Davis or Kuijiken "London" Symphonies (93-101) HAYDN Mosaiques or Kodaly quartets Or start with opus 9, and take it from there. -

With a Rich History Steeped in Tradition, the Courage to Stand Apart and An

With a rich history steeped in tradition, the courage to stand apart and an enduring joy of discovery, the Wiener Symphoniker are the beating heart of the metropolis of classical music, Vienna. For 120 years, the orchestra has shaped the special sound of its native city, forging a link between past, present and future like no other. In Andrés Orozco-Estrada - for several years now an adopted Viennese - the orchestra has found a Chief Conductor to lead this skilful ensemble forward from the 20-21 season onward, and at the same time revisit its musical roots. That the Wiener Symphoniker were formed in 1900 of all years is no coincidence. The fresh wind of Viennese Modernism swirled around this new orchestra, which confronted the challenges of the 20th century with confidence and vision. This initially included the assured command of the city's musical past: they were the first orchestra to present all of Beethoven's symphonies in the Austrian capital as one cycle. The humanist and forward-looking legacy of Beethoven and Viennese Romanticism seems tailor-made for the Symphoniker, who are justly leaders in this repertoire to this day. That pioneering spirit, however, is also evident in the fact that within a very short time the Wiener Symphoniker rose to become one of the most important European orchestras for the premiering of new works. They have given the world premieres of many milestones of music history, such as Anton Bruckner's Ninth Symphony, Arnold Schönberg's Gurre-Lieder, Maurice Ravel's Piano Concerto for the Left Hand and Franz Schmidt's The Book of the Seven Seals - concerts that opened a door onto completely new worlds of sound and made these accessible to the greater masses. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Gustav Mahler Born July 7, 1860, Kalischt, Bohemia. Died May 18, 1911, Vienna, Austria. Symphony No. 9 in D Major Mahler began his ninth symphony in the spring of 1909 and on April 1, 1910, he told the conductor Bruno Walter that the score was complete. Walter conducted the first performance with the Vienna Philharmonic on June 26, 1912. The score calls for four flute s and piccolo, four oboes and english horn, three clarinets, E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet, four bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, bass drum, tam -tam, triangle, glockenspiel, chimes, two harps, and strings. Performance time is approximately eighty -one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony were given at Orchestra Hall on April 6 and 7, 1950, with George Szell conductin g. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on November 30, December 1, 2, and 5, 1995, with Pierre Boulez conducting. The Orchestra first performed this symphony at the Ravinia Festival on August 11, 1979, with Lawrence Foster conducti ng, and most recently on June 28, 1991, with James Levine conducting. Because this symphony is Mahler’s last completed work, and because he died tragically of heart disease at the age of fifty shortly after finishing it, leaving behind his beautiful wife Alma and young daughter Anna, it’s often considered both his farewell and his most deeply personal score. Bruno Walter, who conducted the premiere thirteen months after Mahler’s death, said that he recognized the composer’s own gait in the limping rhythm o f the march at the climax of the first movement. -

CLASSICAL DISCS A\D TAPES Reviewed by RICHARD FREED DAVID HALL GEORGE JELLINEK IGOR KIPNIS PAUL KRESH ERIC SALZMAN

CLASSICAL DISCS A\D TAPES Reviewed by RICHARD FREED DAVID HALL GEORGE JELLINEK IGOR KIPNIS PAUL KRESH ERIC SALZMAN RECORDINGS OF SPECIALMERIT Emperor with Karajan is perhaps even more Rachmaninoff Second Concerto, may be as- impressive. It is big, bold, and genuinely sym- tonished by the lusty, assertive virtuosity dis- BEETHOVEN: Piano Concerto No. 5, in Elicit phonic in concept, not stormy but truly majes- played here. Walter, as in all of his finest re- Major, Op. 73 ("Emperor"). Alexis Weissen- tic in the outer movements and achieving a cordings, simply makes one feel he is allowing berg (.piano); Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, dramatically contrasting level of intimacy in the music to speak for itself, with no gratui- Herbert von Karajan cond. ANGEL S-37062 the middle one. The mutuality between soloist tous overlay of "interpretation," and the or- $6.98. and conductor is extraordinary. A few phras- chestra itself is heartbreakingly beautiful. It Performance: One of the best es here and there are a little fussy, but never doesn't take more than the first entry of the Recording: Very good enough to get in the way of the sweeping of horns in the second subject to remind one that fect, both viscerally exciting and deeply satis- the prewar Vienna Philharmonic was glo- BEETHOVEN: Piano Concerto No. 5, in Elicit fying after repeated hearings. The sound is riously unique, whether playing the Emperor Major, Op. 73 ("Emperor"). Walter Gieseking rich and full-bodied, and in every respect this Concerto or the Emperor Waltz. This was, I (piano);ViennaPhilharmonicOrchestra, is one of the best Emperors around. -

NIKOLAI KORNDORF: a BRIEF INTRODUCTION by Martin Anderson Nikolai Korndorf Had a Clear Image of What Kind of a Composer He Was

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics will be exploring it. To link label and listener directly we have launched the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you two free CDs when you join (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. 8 TOCC 0128 Korndorf.indd 1 26/03/2012 17:30 NIKOLAI KORNDORF: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION by Martin Anderson Nikolai Korndorf had a clear image of what kind of a composer he was. -

And the Mahler Ninth

Eight members of the Vienna Octet play under the benign circumspection of the Mozart family there are mountain brooks that are more (or less) Ninth Symphony has not lacked outstanding record- perfect than other mountain brooks, but who would ed performances. Among the presently available think of criticizing a mountain brook in the first readings of this vast and complex masterpiece, Bruno place? Walter's 1962 version and subsequent ones by Dvoiak and his music belong to another genera- Georg Solti and Leonard Bernstein stand out in their tion, but a work such as his G Major Quintet is in own distinctive ways. fact more closely related to early Romanticism than To this select company must now be added Phil- to the Lisztian/Wagnerian nineteenth century. Its ips' new recording of the symphony by the Amster- richness is due in large part to the use of the double dam Concertgebouw Orchestra under conductor bass-here perfectly played and reproduced. Bernard Haitink. It is, for me, the disc realization Except for what seems to be a bit of inner -groove that comes closest to revealing the totality of Mahl- distortion toward the end of the Spohr, these are er's vision in this work, thanks not only to a most superbly produced discs in every dimension. Inter- probing search of the music's expressive and textur- estingly enough, there appear to be eleven "mem- al -architectural inner substance, but by virtue of su- bers" of the Vienna Octet. Eric Salzman perior recorded sound. From the foreboding opening measures, through KREUTZER: Grand Septet, in E -flat Major, Op. -

THE KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION CHOPIN PIANO COMPETITION HISTORICAL OVERVIEW in 1949, to Mark the Centennial of the Death of Fryderyk

THE KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION CHOPIN PIANO COMPETITION HISTORICAL OVERVIEW In 1949, to mark the centennial of the death of Fryderyk Chopin, the Kosciuszko Foundation’s Board of Trustees authorized a National Committee to encourage observance of the anniversary through concerts and programs throughout the United States. Howard Hansen, then Director of the Eastman School of Music, headed this Committee, which included, among others, Claudio Arrau, Vladimir Horowitz, Serge Koussevitzky, Claire Booth Luce, Eugene Ormandy, Artur Rodzinski, George Szell, and Bruno Walter. The Chopin Centennial was inaugurated by Witold Malcuzynski at Carnegie Hall on February 14, 1949. A repeat performance was presented by Malcuzynski eight days later, on Chopin’s birthday, in the Kosciuszko Foundation Gallery. Abram Chasins, composer, pianist, and music director of the New York Times radio stations WQXR and WQWQ, presided at the evening and opened it with the following remarks: In seeking to do justice to the memory of a musical genius, nothing is so eloquent as a presentation of the works through which he enriched our musical heritage. … In his greatest work, Chopin stands alone … Throughout the chaos, the dissonance of the world, Chopin’s music has been for many of us a sanctuary … It is entirely fitting that this event should take place at the Kosciuszko Foundation House. This Foundation is the only institution which we have in America which promotes cultural relations between Poland and America on a non-political basis. It has helped to understand the debt which mankind owes to Poland’s men of genius. At the Chopin evening at the Foundation, two contributions were made. -

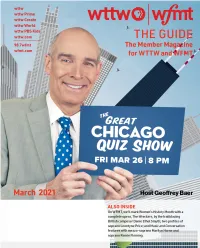

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

Home of the Baker Museum and the Naples Philharmonic 5833 Pelican

Home of The Baker Museum and the Naples Philharmonic 5833 Pelican Bay Boulevard Naples, FL 34108-2740 Andrey Boreyko Sharon and Timothy Ubben Music Director Now in his eighth and final season as music director of Artis—Naples, Andrey Boreyko’s inspiring leadership has raised the artistic standard of the Naples Philharmonic. Andrey concludes his tenure as music director by continuing to explore connections between art forms through interdisciplinary thematic programming. Significant projects he has led include pairing Ballet Russes-inspired contemporary visual artworks of Belgian artist Isabelle de Borchgrave with performances of Stravinsky’s Pulcinella and The Firebird, as well as commissioning a series of compact pieces by composers including Giya Kancheli to pair with an art exhibition featuring small yet personal works by artists such as Picasso and Calder that were created as special gifts for the renowned collector Olga Hirshhorn. The 2021-22 season marks Andrey’s third season as music and artistic director of the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra. Their planned engagements this season include performances at the Eufonie Festival, the final and prizewinners’ concerts of the 18th Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition in Warsaw, and the orchestra’s 120th birthday celebration. They also plan to tour across Poland and the U.S. Highlights of previous seasons have included major tours with the State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia (to Hamburg, Cologne, Frankfurt and Munich) and the Filarmonica della Scalla (to Ljubljana, Rheingau, -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia La Biennale Di Venezia President Presents Roberto Cicutto

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia La Biennale di Venezia President presents Roberto Cicutto Board The Disquieted Muses. Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como in collaboration with Director General Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche Andrea Del Mercato and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself.