George Neilson, "Trial by Combat" (1890)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duelling and Militarism Author(S): A

Duelling and Militarism Author(s): A. Forbes Sieveking Source: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 11 (1917), pp. 165-184 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3678440 Accessed: 26-06-2016 04:11 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press, Royal Historical Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Royal Historical Society This content downloaded from 128.192.114.19 on Sun, 26 Jun 2016 04:11:58 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms DUELLING AND MILITARISM By A. FORBES SIEVEKING, F.S.A., F.R.Hist. Soc. Read January 18, 1917 IT is not the object of this paper to suggest that there is any historical foundation for the association of a social or even a national practice of duelling with the more recent political manifestation, which is usually defined according to our individual political beliefs ; far less is it my intention to express any opinion of my own on the advantages or evils of a resort to arms as a means of settling the differences that arise between individuals or nations. -

The Earldom of Kent from C. 1050 Till 1189

The earldom of Kent from c. 1050 till 1189 Colin Flight In the 1160s, when the sheriff of Kent presented himself at the Exchequer, there were three accounts which he was required to settle every year: ‘the farm of the county’ (firma comitatus), ‘the farm of the county by tale’ (firma comitatus numero), and ‘the farm of the land of the bishop of Bayeux’ (firma terre episcopi baiocensis). The first account was reckoned blanch,1 the other two both numero, ‘by tale’. During the first few years of the new reign, it seems to have been uncertain exactly how much the sheriff was answerable for, as far as the second and third accounts were concerned. By about 1160, any doubts had been resolved, and from then onwards the totals 1 remained constant: £412 7s. 62 d. blanch for the farm of the county, £165 13s. 4d. for the farm of the county by tale, £289 13s. 7d. for the farm of the land of the bishop of Bayeux. The sheriff had to produce this money; or else he had to explain, item by item, why he should not be required to pay the full amount. As they appear on the pipe rolls,2 the first two accounts are mixed up together, with blanch and numero items interspersed. Confusing though this may seem to us, the Exchequer was accustomed to dealing with complications of this kind: it seems almost to have enjoyed them. The two accounts were treated as components of a single 1 For an explanation of this term the reader may wish to consult the appendix (below, p. -

The Sinclair Macphersons

Clan Macpherson, 1215 - 1550 How the Macphersons acquired their Clan Lands and Independence Reynold Macpherson, 20 January 2011 Not for sale, free download available from www.reynoldmacpherson.ac.nz Clan Macpherson, 1215 to 1550 How the Macphersons acquired their traditional Clan Lands and Independence Reynold Macpherson Introduction The Clan Macpherson Museum (see right) is in the village of Newtonmore, near Kingussie, capital of the old Highland district of Badenoch in Scotland. It presents the history of the Clan and houses many precious artifacts. The rebuilt Cluny Castle is nearby (see below), once the home of the chief. The front cover of this chapter is the view up the Spey Valley from the memorial near Newtonmore to the Macpherson‟s greatest chief; Col. Ewan Macpherson of Cluny of the ‟45. Clearly, the district of Badenoch has long been the home of the Macphersons. It was not always so. This chapter will make clear how Clan Macpherson acquired their traditional lands in Badenoch. It means explaining why Clan Macpherson emerged from the Old Clan Chattan, was both a founding member of the Chattan Confederation and yet regularly disputed Clan Macintosh‟s leadership, why the Chattan Confederation expanded and gradually disintegrated and how Clan Macpherson gained its property and governance rights. The next chapter will explain why the two groups played different roles leading up to the Battle of Culloden in 1746. The following chapter will identify the earliest confirmed ancestor in our family who moved to Portsoy on the Banff coast soon after the battle and, over the decades, either prospered or left in search of new opportunities. -

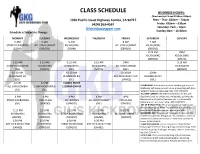

Class Schedule

CLASS SCHEDULE BUSINESS HOURS: (Wednesdays Closed 1130am-330pm) 1930 Pacific Coast Highway Lomita, CA 90717 Mon – Thur: 830am – 730pm (424) 263-4567 Friday: 830am – 630pm Saturday: 7am – 12pm Gilskickboxinggym.com Sunday: 8am – 10:30am Schedule is Subject to Change. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 7 AM STRAP KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (JOHN) (SERGIO) (JOHN) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) 8:15 AM 8AM KICKBOXING KICKBOXING (SERGIO) (MAYA) 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9AM 9:15 AM STRAP KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (SERGIO) 10:30 AM 10:30 AM 10:30AM 10AM BEGINNERS BJJ BEGINNERS BJJ ART OF 8 MUAY THAI BEGINNERS BJJ (GIL) (GIL) (JAMES) (GIL) 12 PM 12 PM CLOSED FROM KICKBOXING: A 60-minute workout combining a series of ALL GYM COMBAT STRAP KICKBOXING 1130AM-330PM kickboxing techniques you will do on a heavy bag with body (Gil) (GIL) weight muscle endurance exercises. (NO CONTACT) ALL GYM COMBAT: We use the whole gym for this one. 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4PM Equipment such as battle ropes, Kettlebells, agility ladder, Bungee cable, Grappling Dummies, etc. combined with STRAP KICKBOXING KIDS CLASS KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KIDS CLASS Kickboxing to train like a fighter. (NO CONTACT) (GIL) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) (GIL) (SERGIO) ART OF 8 MUAY THAI: This Class focuses on teaching you the fundamentals of Muay Thai Kickboxing. You will learn 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15PM how to hold Thai pads and gain real striking skills. -

The Death of Dueling Wade Ellett

59 60 The Death of Dueling feuds, and a chivalric code of honor emphasizing virtue.6 Eventually this code of honor evolved into the upper class and nobility’s theory of courtesy and the idea of the “gentleman”. This resulted in the adoption of one-on-one combat to settle affairs in 7 the sixteenth century. The duel of honor, as recognized from entertainment media, was based primarily on the Italian Wade Ellett Renaissance idea of the gentleman and arrived in England in the 1570s.8 The practice was welcomed by the upper classes, who had Violence in some form or another has probably always long been awaiting a method to solve disputes. But the warm existed. Civilization did not end violence, it merely provided a reception was not shared by royalty, and Queen Elizabeth I framework to ritualize and institutionalize violent acts. Once outlawed the judicial duel in 1571.9 Her attempts to remove the civilized, ritual violence became almost entirely a man’s realm.1 practice from England failed and dueling quickly gained Ritual violence took many forms; but, without a doubt, one of the popularity.10 most romanticized was the duel. Dueling differed from wartime Dueling thrived in England for nearly three centuries; violence and barroom brawls because dueling placed two however, the practice eventually came to an end in 1852, when the opponents, almost always of similar social class, against one last recorded English duel was fought. There were many another in a highly stylized form of combat.2 Fisticuffs and war contributing factors to the practice’s end. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Trial by Battle*

Trial by Battle Peter T. Leesony Abstract For over a century England’s judicial system decided land disputes by ordering disputants’legal representatives to bludgeon one another before an arena of spectating citizens. The victor won the property right for his principal. The vanquished lost his cause and, if he were unlucky, his life. People called these combats trials by battle. This paper investigates the law and economics of trial by battle. In a feudal world where high transaction costs confounded the Coase theorem, I argue that trial by battle allocated disputed property rights e¢ ciently. It did this by allocating contested property to the higher bidder in an all-pay auction. Trial by battle’s “auctions” permitted rent seeking. But they encouraged less rent seeking than the obvious alternative: a …rst- price ascending-bid auction. I thank Gary Becker, Omri Ben-Shahar, Peter Boettke, Chris Coyne, Ariella Elema, Lee Fennell, Tom Ginsburg, Mark Koyama, William Landes, Anup Malani, Jonathan Masur, Eric Posner, George Souri, participants in the University of Chicago and Northwestern University’s Judicial Behavior Workshop, the editors, two anonymous reviewers, and especially Richard Posner and Jesse Shapiro for helpful suggestions and conversation. I also thank the Becker Center on Chicago Price Theory at the University of Chicago, where I conducted this research, and the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. yEmail: [email protected]. Address: George Mason University, Department of Economics, MS 3G4, Fairfax, VA 22030. 1 “When man is emerging from barbarism, the struggle between the rising powers of reason and the waning forces of credulity, prejudice, and custom, is full of instruction.” — Henry C. -

World Combat Games Brochure

Table of Contents 4 5 6 What is GAISF? What are the World Roles and Combat Games? responsibilities 7 8 10 Attribution Culture, ceremonies Media promotion process and festival events, and production and legacy 12 13 14 List of sports Venue Aikido at the World setup Armwrestling Combat Games Boxing 15 16 17 Judo Kendo Muaythai Ju-jitsu Kickboxing Sambo Karate Savate 18 19 Sumo Wrestling Taekwondo Wushu 4 WORLD COMBAT GAMES WORLD COMBAT GAMES 5 What is GAISF? What are the World Combat Games? The united voice of sports - protecting the interests of International A breathtaking event, showcasing Federations the world’s best martial arts and GAISF is the Global Association of International Founded in 1967, GAISF is a key pillar of the combat sports Sports Federations, an umbrella body composed wider sports movement and acts as the voice of autonomous and independent International for its 125 Members, Associate Members and Sports Federations, and other international sport observers, which include both Olympic and non- and event related organisations. Olympic sports organisations. THE BENEFITS OF THE NUMBERS OF HOSTING THE WORLD THE GAMES GAISF MULTISPORT GAMES COMBAT GAMES Up to Since 2010, GAISF has successfully delivered GAISF serves as the conduit between ■ Bring sport to life in your city multisport games for combat sports and martial International Sports Federations and host cities, ■ Provide worldwide multi-channel media exposure 35 disciplines arts, mind games and urban orientated sports. bringing benefits to both with a series of right- ■ Feature the world’s best athletes sized events that best consider the needs and ■ Establish a perfect bridge between elite sport and Approximately resources of all involved. -

Teacher's Guide to the Core Classics Edition of Robin Hood

Teacher’s Guide to The Core Classics Edition of Robin Hood By Judy Gardner Copyright 2003 Core Knowledge Foundation This online edition is provided as a free resource for the benefit of Core Knowledge teachers and others using the Core Classics edition of Robin Hood. This edition is retold from Old Ballads by J. Walker McSpadden. Resale of these pages is strictly prohibited. Publisher’s Note We are happy to make available this Teacher’s Guide to the Core Classics version of Robin Hood and His Merry Outlaws prepared by Judy Gardner. We are presenting it and other guides in an electronic format so that they are accessible to as many teachers as possible. Core Knowledge does not endorse any one method of teaching a text; in fact we encourage the creativity involved in a diversity of approaches. At the same time, we want to help teachers share ideas about what works in the classroom. In this spirit we invite you to use any or all of the ways Judy Gardner has found to make this book enjoyable and understandable to fourth grade students. We hope that you find the background material, which is addressed specifically to teachers, useful preparation for teaching the book. We also hope that the vocabulary and grammar exercises designed for students will help you integrate the reading of literature with the development of skills in language arts. Most of all, we hope this guide helps to make Robin Hood a marvelous adventure in reading for both you and your students. 2 Contents Publisher’s Note.....................................................................................................................2 -

Montesquieu on the History and Geography of Political Liberty

Montesquieu on the History and Geography of Political Liberty Author: Rebecca Clark Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:103616 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College Graduate School of Arts & Sciences Department of Political Science MONTESQUIEU ON THE HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY OF POLITICAL LIBERTY A dissertation by REBECCA RUDMAN CLARK submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 © Copyright by REBECCA RUDMAN CLARK 2012 Abstract Montesquieu on the History and Geography of Political Liberty Rebecca R. Clark Dissertation Advisor: Christopher Kelly Montesquieu famously presents climate and terrain as enabling servitude in hot, fertile climes and on the exposed steppes of central Asia. He also traces England’s exemplary constitution, with its balanced constitution, independent judiciary, and gentle criminal practices, to the unique conditions of early medieval northern Europe. The English “found” their government “in the forests” of Germany. There, the marginal, variegated terrain favored the dispersion of political power, and a pastoral way of life until well into the Middle Ages. In pursuing a primitive honor unrelated to political liberty as such, the barbaric Franks accidentally established the rudiments of the most “well-tempered” government. His turn to these causes accidental to human purposes in Parts 3-6 begins with his analysis of the problem of unintended consequences in the history of political reform in Parts 1-2. While the idea of balancing political powers in order to prevent any one individual or group from dominating the rest has ancient roots, he shows that it has taken many centuries to understand just what needs to be balanced, and to learn to balance against one threat without inviting another. -

The Role of the Philistines in the Hebrew Bible*

Teresianum 48 (1997/1) 373-385 THE ROLE OF THE PHILISTINES IN THE HEBREW BIBLE* GEORGE J. GATGOUNIS II Although hope for discovery is high among some archeolo- gists,1 Philistine sources for their history, law, and politics are not yet extant.2 Currently, the fullest single source for study of the Philistines is the Hebrew Bible.3 The composition, transmis sion, and historical point of view of the biblical record, however, are outside the parameters of this study. The focus of this study is not how or why the Hebrews chronicled the Philistines the way they did, but what they wrote about the Philistines. This study is a capsule of the biblical record. Historical and archeo logical allusions are, however, interspersed to inform the bibli cal record. According to the Hebrew Bible, the Philistines mi * Table of Abbreviations: Ancient Near Eastern Text: ANET; Biblical Archeologist: BA; Biblical Ar- cheologist Review: BAR; Cambridge Ancient History: CAH; Eretz-Israel: E-I; Encyclopedia Britannica: EB; Journal of Egyptian Archeology: JEA; Journal of Near Eastern Studies: JNES; Journal of the Study of the Old Testament: JSOT; Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement: PEFQSt; Vetus Testamentum: VT; Westminster Theological Journal: WTS. 1 Cf. Law rence S tager, “When the Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR (Mar.-April 1991),17:36. Stager is hopeful: When we do discover Philistine texts at Ashkelon or elsewhere in Philistia... those texts will be in Mycenaean Greek (that is, in Linear B or same related script). At that moment, we will be able to recover another lost civilization for world history. -

The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood

The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood Howard Pyle This eBook was designed and published by Planet PDF. For more free eBooks visit our Web site at http://www.planetpdf.com/. To hear about our latest releases subscribe to the Planet PDF Newsletter. The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood PREFACE FROM THE AUTHOR TO THE READER You who so plod amid serious things that you feel it shame to give yourself up even for a few short moments to mirth and joyousness in the land of Fancy; you who think that life hath nought to do with innocent laughter that can harm no one; these pages are not for you. Clap to the leaves and go no farther than this, for I tell you plainly that if you go farther you will be scandalized by seeing good, sober folks of real history so frisk and caper in gay colors and motley that you would not know them but for the names tagged to them. Here is a stout, lusty fellow with a quick temper, yet none so ill for all that, who goes by the name of Henry II. Here is a fair, gentle lady before whom all the others bow and call her Queen Eleanor. Here is a fat rogue of a fellow, dressed up in rich robes of a clerical kind, that all the good folk call my Lord Bishop of Hereford. Here is a certain fellow with a sour temper and a grim look— the worshipful, the Sheriff of Nottingham. And here, above all, is a great, tall, merry fellow that roams the greenwood and joins in homely sports, and sits beside the Sheriff at merry feast, which same beareth the 2 of 493 The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood name of the proudest of the Plantagenets—Richard of the Lion’s Heart.