Do Southern Boobooks Ninox Novaeseelandiae Duet?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITES Norfolk Island Boobook Review

Original language: English AC28 Doc. 20.3.6 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Twenty-eighth meeting of the Animals Committee Tel Aviv (Israel), 30 August-3 September 2015 Interpretation and implementation of the Convention Species trade and conservation Periodic review of species included in Appendices I and II (Resolution Conf 14.8 (Rev CoP16)) PERIODIC REVIEW OF NINOX NOVAESEELANDIAE UNDULATA 1. This document has been submitted by Australia.1 2. After the 25th meeting of the Animals Committee (Geneva, July 2011) and in response to Notification No. 2011/038, Australia committed to the evaluation of Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata as part of the Periodic review of the species included in the CITES Appendices. 3. This taxon is endemic to Australia. 4. Following our review of the status of this species, Australia recommends the transfer of Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata from CITES Appendix I to CITES Appendix II, in accordance with provisions of Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev CoP16), Annex 4 precautionary measure A.1. and A.2.a) i). 1 The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC28 Doc. 20.3.6 – p. 1 AC28 Doc. 20.3.6 Annex CoP17 Prop. xx CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ DRAFT PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE APPENDICES (in accordance with Annex 4 to Resolution Conf. -

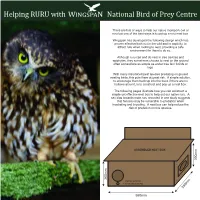

(Ruru) Nest Box

Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre There are lots of ways to help our native morepork owl or ruru but one of the best ways is to put up a ruru nest box. Wingspan has developed the following design which has proven effective both out in the wild and in captivity, to attract ruru when looking to nest, providing a safe environment for them to do so. Although ruru can and do nest in tree cavities and epiphytes, they sometimes choose to nest on the ground often somewhere as simple as under tree fern fronds or logs. With many introduced pest species predating on ground nesting birds, this puts them at great risk. A simple solution, to encourage them back up into the trees if there are no hollows around, is to construct and pop up a nest box. The following pages illustrate how you can construct a simple yet effective nest box to help out our native ruru. A sex bias towards male ruru recorded in one study suggests that females may be vulnerable to predation when incubating and brooding. A nest box can help reduce the risk of predation on this species. ASSEMBLED NEST BOX 300mm 260mm ENTRY PERCH < ATTACHED HERE 260mm 580mm Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre MATERIALS: + 12mm tanalised plywood + Galvanised screws 30mm (x39) Galvanised screws 20mm (x2 for access panel) DIMENSIONS: Top: 300 x 650mm Front: 245 x 580mm Back: 350 x 580mm Base: 260 x 580mm Ends: 260 x 260 x 300mm Door: 150 x 150mm Entrance & Access Holes: 100mm + + + TOP + 300x650mm + + + + + + + + BACK 350x580mm + + + + ACCESS + + FRONT + HOLE + 100x100 ENTRANCE 245x580mm HOLE END 100x100 END 260x260x300mm 260x260x300mm + + + + + + + + + + + ACCESS COVER 150x150mm + BASE + 260x580mm + + + + + Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre INSTRUCTIONS FOR RURU NEST BOX ASSEMBLY: Screw front and back onto inside edge of base (4 screws along each edge using pre-drilled holes). -

Observations on the Biology of the Powerful Owl Ninox Strenua in Southern Victoria by E.G

VOL. 16 (7) SEPTEMBER 1996 267 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1996, 16, 267-295 Observations on the Biology of the Powerful Owl Ninox strenua in Southern Victoria by E.G. McNABB, P.O. \IJ~~ 408, Emerald, Victoria 3782 . \. Summary A pair of Powerful Owls Ninox strenua was studied at each of two sites near Melbourne, Victoria, for three years (1977-1979) and 15 years (1980-1994 inclusive) respectively, by diurnal and nocturnal observation. Home ranges were.mapped, nest sites characterised and breeding chronology and success monitored. General observations at these and eight other sites, of roosting, courting, nesting, parental and juvenile behaviour, fledgling mortality, hunting, interspecific conflicts, bathing, and camouflage posing, are presented. The regularly used parts of the home ranges of two pairs were each estimated as c. 300 ha, although for one pair this applied only to the breeding season. One pair used seven nest trees in 15 years, commonly two or three times each (range 1-4 times) over consecutive years before changing trees. Nest-switching may have been encouraged by human inspection of hollows. Nest entrances were 8-40 m (mean 22 m) above ground. The owls clearly preferred the larger and older trees (estimated 350-500+ years old), beside permanent creeks rather than seasonal streams, and in gullies or on sheltered aspects rather than ridges. Laying dates were spread over a month from late May, with a peak in mid June. The breeding cycle occupied three months from laying to fledging, of which the nestling period lasted 8-9 weeks. Breeding success was 1.4 young per pair per year and 94% nest success; early nests in gullies were more successful than late nests on slopes. -

Approved Recovery Plan for Large Forest Owls

Approved NSW Recovery Plan Recovery Plan for the Large Forest Owls Powerful Owl Sooty Owl Masked Owl Ninox strenua Tyto tenebricosa Tyto novaehollandiae October 2006 Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW), 2006. This work is copyright, however, material presented in this plan may be copied for personal use or educational purposes, providing that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Apart from this and any other use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from DEC. This plan should be cited as follows: Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) (2006). NSW Recovery Plan for the Large Forest Owls: Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua), Sooty Owl (Tyto tenebricosa) and Masked Owl (Tyto novaehollandiae) DEC, Sydney. For further information contact: Large Forest Owl Recovery Coordinator Biodiversity Conservation Unit Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) PO Box A290 Sydney South NSW 1232 Published by: Department of Environment and Conservation NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 1 74137 995 4 DEC 2006/413 October 2006 Cover photographs: Powerful Owl, R. Jackson, Sooty Owl, D. Hollands and Masked Owl, M. Todd. Approved Recovery Plan for Large Forest Owls Recovery Plan for the Large Forest Owls Executive Summary This document constitutes the formal New South Wales State recovery plan for the three large forest owls of NSW - the Powerful Owl Ninox strenua (Gould), Sooty Owl Tyto tenebricosa (Gould) and Masked Owl Tyto novaehollandiae (Stephens). -

Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles Acutipennis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Evolution of Quiet Flight in Owls (Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles acutipennis) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology by Krista Le Piane December 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin Dr. Khaleel A. Razak Copyright by Krista Le Piane 2020 The Dissertation of Krista Le Piane is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my Oral Exam Committee: Dr. Khaleel A. Razak (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, Dr. Mark Springer, Dr. Jesse Barber, and Dr. Scott Curie. Thank you to my Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, and Dr. Khaleel A. Razak for their encouragement and help with this dissertation. Thank you to my lab mates, past and present: Dr. Sean Wilcox, Dr. Katie Johnson, Ayala Berger, David Rankin, Dr. Nadje Najar, Elisa Henderson, Dr. Brian Meyers Dr. Jenny Hazelhurst, Emily Mistick, Lori Liu, and Lilly Hollingsworth for their friendship and support. I thank the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM), the California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) at UC Berkeley, the American Museum of Natural History (ANMH), and the Natural History Museum (NHM) in Tring for access to specimens used in Chapter 1. I would especially like to thank Kimball Garrett and Allison Shultz for help at LACM. I also thank Ben Williams, Richard Jackson, and Reddit user NorthernJoey for permission to use their photos in Chapter 1. Jessica Tingle contributed R code and advice to Chapter 1 and I would like to thank her for her help. -

The Touch of Nature Has Made the Whole World Kin: Interspecies Kin Selection in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Honors Theses 2015 The Touch of Nature Has Made the Whole World Kin: Interspecies Kin Selection in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Laura E. Jenkins Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/honors Part of the Animal Law Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, and the Human Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Jenkins, Laura E., "The Touch of Nature Has Made the Whole World Kin: Interspecies Kin Selection in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora" (2015). Honors Theses. 74. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/honors/74 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 2015 The Touch of Nature Has Made the Whole World Kin INTERSPECIES KIN SELECTION IN THE CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA LAURA E. JENKINS Abstract The unequal distribution of legal protections on endangered species has been attributed to the “charisma” and “cuteness” of protected species. However, the theory of kin selection, which predicts the genetic relationship between organisms is proportional to the amount of cooperation between them, offers an evolutionary explanation for this phenomenon. In this thesis, it was hypothesized if the unequal distribution of legal protections on endangered species is a result of kin selection, then the genetic similarity between a species and Homo sapiens is proportional to the legal protections on that species. -

A Revision of the Australian Owls (Strigidae and Tytonidae)

A REVISION OF THE AUSTRALIAN OWLS (STRIGIDAE AND TYTONIDAE) by G. F. MEES Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden1) INTRODUCTION When in December 1960 the R.A.O.U. Checklist Committee was re- organised and the various tasks in hand were divided over its members, the owls were assigned to the author. While it was first thought that only the Boobook Owl, the systematics of which have been notoriously confused, would need thorough revision and that as regards the other species existing lists, for example Peters (1940), could be followed, it became soon apparent that it was impossible to make a satisfactory list without revision of all species. In this paper the four Australian species of Strigidae are fully revised, over their whole ranges, and the same has been done for Tyto tenebricosa. Of the other three Australian Tytonidae, however, only the Australian races have been considered: these species have a wide distribution (one of them virtually world-wide) and it was not expected that the very considerable amount of extra work needed to include extralimital races would be justified by results. Considerable attention has been paid to geographical distribution, and it appears that some species are much more restricted in distribution than has generally been assumed. A map of the distribution of each species is given; these maps are mainly based on material personally examined, and only when they extended the range as otherwise defined, have I made use of reliable field observations and material published but not seen by me. From the section on material examined it will be easy to trace the localities; where other information has been used, the reference follows the locality. -

BIRDS NEW ZEALAND Te Kahui Matai Manu O Aotearoa No.24 December 2019

BIRDS NEW ZEALAND Te Kahui Matai Manu o Aotearoa No.24 December 2019 The Magazine of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand NO.24 DECEMBER 2019 Proud sponsors of Birds New Zealand From the President's Desk Find us in your local 3 New World or PAKn’ Save 4 NZ Bird Conference & AGM 2020 5 First Summer of NZ Bird Atlas 6 Birds New Zealand Research Fund 2019 8 Solomon Islands – Monarchs & Megapodes 12 The Inspiration of Birds – Mike Ashbee 15 Aka Aka swampbird Youth Camp 16 Regional Roundup PUBLISHERS Published on behalf of the members of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand 19 Bird News (Inc), P.O. Box 834, Nelson 7040, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] Website: www.birdsnz.org.nz Editor: Michael Szabo, 6/238 The Esplanade, Island Bay, Wellington 6023. Email: [email protected] Tel: (04) 383 5784 COVER IMAGE ISSN 2357-1586 (Print) ISSN 2357-1594 (Online) Morepork or Ruru. Photo by Mike Ashbee. We welcome advertising enquiries. Free classified ads for members are at the https://www.mikeashbeephotography.com/ editor’s discretion. Articles or illustrations related to birds in New Zealand and the South Pacific region are welcome in electronic form, such as news about birds, members’ activities, birding sites, identification, letters, reviews, or photographs. Letter to the Editor – Conservation Copy deadlines are 10th Feb, May, Aug and 1st Nov. Views expressed by contributors do not necessarily represent those of OSNZ (Inc) or the editor. Birds New Zealand has a proud history of research, but times are changing and most New Zealand bird species are declining in numbers. -

Conservation Status of New Zealand Birds, 2008

Notornis, 2008, Vol. 55: 117-135 117 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2008 Colin M. Miskelly* Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand [email protected] JOHN E. DOWDING DM Consultants, P.O. Box 36274, Merivale, Christchurch 8146, New Zealand GRAEME P. ELLIOTT Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 5, Nelson 7042, New Zealand RODNEY A. HITCHMOUGH RALPH G. POWLESLAND HUGH A. ROBERTSON Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand PAUL M. SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand R. PAUL SCOFIELD Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8001, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand Abstract An appraisal of the conservation status of the post-1800 New Zealand avifauna is presented. The list comprises 428 taxa in the following categories: ‘Extinct’ 20, ‘Threatened’ 77 (comprising 24 ‘Nationally Critical’, 15 ‘Nationally Endangered’, 38 ‘Nationally Vulnerable’), ‘At Risk’ 93 (comprising 18 ‘Declining’, 10 ‘Recovering’, 17 ‘Relict’, 48 ‘Naturally Uncommon’), ‘Not Threatened’ (native and resident) 36, ‘Coloniser’ 8, ‘Migrant’ 27, ‘Vagrant’ 130, and ‘Introduced and Naturalised’ 36. One species was assessed as ‘Data Deficient’. The list uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System, which provides greater resolution of naturally uncommon taxa typical of insular environments than the IUCN threat ranking system. New Zealand taxa are here ranked at subspecies level, and in some cases population level, when populations are judged to be potentially taxonomically distinct on the basis of genetic data or morphological observations. -

New Zealand 9Th – 25Th January 2020 (27 Days) Chatham Islands Extension 25Th – 28Th January 2020 (4 Days) Trip Report

New Zealand 9th – 25th January 2020 (27 Days) Chatham Islands Extension 25th – 28th January 2020 (4 Days) Trip Report The Rare New Zealand Storm Petrel, Hauraki Gulf by Erik Forsyth Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader Erik Forsyth Trip Report – RBL New Zealand – Comprehensive I 2020 2 Tour Summary After a brief get together this morning, we headed to a nearby estuary to look for wading birds on the incoming tide. It worked out well for us as the tide was pushing in nicely and loads of Bart-tailed Godwits could be seen coming closer towards us. Scanning through the flock we could found many Red Knot as well as our target bird for this site, the endemic Wrybill. About 100 of the latter were noted and great scope looks were enjoyed. Other notable species included singletons of Double-banded and New Zealand Plovers as well as Paradise Shelduck all of which were endemics! After this good start, we headed North to the Muriwai Gannet Colony, arriving late morning. The breeding season was in full The Endangered Takahe, Tiritiri Matangi Island swing with many Australasian Gannets by Erik Forsyth feeding large chicks. Elegant White-fronted Terns were seen over-head and Silver and Kelp Gulls were feeding chicks as well. In the surrounding Flax Bushes, a few people saw the endemic Tui, a large nectar-feeding honeyeater as well as a Dunnock. From Muriwai, we drove to east stopping briefly for lunch at a roadside picnic area. Arriving at our hotel in the late afternoon, we had time to rest and prepare for our night walk. -

An Investigation of Causes of Disease Among

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. An investigation of causes of disease among wild and captive New Zealand falcons (Falco novaeseelandiae), Australasian harriers (Circus approximans) and moreporks (Ninox novaeseelandiae). A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Veterinary Science at Massey University, Turitea, Palmerston North, New Zealand Mirza Vaseem 2014 ABSTRACT Infectious disease can play a role in the population dynamics of wildlife species. The introduction of exotic birds and mammals into New Zealand has led to the introduction of novel diseases into the New Zealand avifauna such as avian malaria and toxoplasmosis. However the role of disease in New Zealand’s raptor population has not been widely reported. This study aims at investigating the presence and prevalence of disease among wild and captive New Zealand falcons (Falco novaeseelandiae), Australasian harrier (Circus approximans) and moreporks (Ninox novaeseelandiae). A retrospective study of post-mortem databases (the Huia database and the Massey University post-mortem database) undertaKen to determine the major causes of mortality in New Zealand’s raptors between 1990 and 2014 revealed that trauma and infectious agents were the most frequently encountered causes of death in these birds. However, except for a single case report of serratospiculosis in a New Zealand falcon observed by Green et al in 2006, no other infectious agents have been reported among the country’s raptors to date in the peer reviewed literature. -

Anticoagulant Rodenticide Exposure in an Australian Predatory Bird Increases with Proximity to Developed Habitat

Science of the Total Environment 643 (2018) 134–144 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Anticoagulant rodenticide exposure in an Australian predatory bird increases with proximity to developed habitat Michael T. Lohr School of Science, Edith Cowan University, 100 Joondalup Drive, Joondalup, Western Australia 6027, Australia HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Anticoagulant rodenticide (AR) exposure rates are poorly studied in Australian wildlife. • ARs were detected in 72.6% of Southern Boobook owls found dead or moribund in Western Australia. • Total AR exposure correlated with prox- imity to developed habitat. • ARsusedonlybylicensedpesticideappli- cators were detected in owls. • Raptors with larger home ranges and more mammal-based diets may be at greater risk of AR exposure. article info abstract Article history: Anticoagulant rodenticides (ARs) are commonly used worldwide to control commensal rodents. Second gener- Received 10 May 2018 ation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs) are highly persistent and have the potential to cause secondary poison- Received in revised form 16 June 2018 ing in wildlife. To date no comprehensive assessment has been conducted on AR residues in Australian wildlife. Accepted 17 June 2018 My aim was to measure AR exposure in a common widespread owl species, the Southern Boobook (Ninox Available online xxxx boobook) using boobooks found dead or moribund in order to assess the spatial distribution of this potential Editor: D. Barcelo threat. A high percentage of boobooks were exposed (72.6%) and many showed potentially dangerous levels of AR residue (N0.1 mg/kg) in liver tissue (50.7%). Multiple rodenticides were detected in the livers of 38.4% of Keywords: boobooks tested.