Mdiittx of ^Djlo^Op^P IN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primo.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU SATURDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2014 (PAGE 13) 67 55 Hawa Bibi Hangroo Teacher Ghulam Nabi Hagroo Anantnag GOVERNMENT OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR 68 56 Shamima Akhter Teacher Gh Hassan Salroo Bejbehara, Anantnag 69 57 Bashir Ahmad Rather Teacher Ab Razak Rather Bahaie, Anantnag 70 98 Shaheena Mehraj Teacher Kh. Mehraj Ud Din Wani Laizbal, Anantnag CIVIL SECRETARIAT: FINANCE DEPARTMENT 71 34 Suraya Amin Teacher Mohd Amin Shapoo Kokernag, Annatnag Cont. School Education Department, Ganderbal Srinagar/Jammu S.No 10th ECM S. No Name of Employee Desig. Decision Adresss Remarks 72 2 Tariq Ahmad Mir Teacher Gh Rasool Mir Bamlina, Kangan Ganderbal 73 3 Qunser Bashir Teacher Bashir Ahmad Shah Khanyar, Srinagar 74 4 Gh. Rasool Mir Teacher Ab Jabbar Mir Drugentengo, Kangan Ganderbal 75 5 Fayaz Ahmad Magray Teacher Gh Mohd Magray Kangan, Ganderbal N O T I F I C A T I O N 76 6 Firdous Rashid Khan Teacher Abdul Rashid Khan Kachgari Masjid, Fatehkadal 77 8 Vijada Maqbool Qadri Teacher Maqbool Ahmad Qadri Soura, Srinagar 78 10 Qaisar Ahmad Bhat Teacher Gh Nabi Bhat Kangan, Kachnabal Sub:- Regularization of Adhoc/Contractual/Consolidated employees. 79 11 Zamrooda Teacher Gh Mohd Mir Kangan, Ganderbal 80 13 Heena Qazi Teacher Qazi Mohd Afzal Ahmad Nagar, Srinagar Vide Notification No. 43 issued under No. DC/PS/Misc- 193/2013 dated 81 16 Danista Syed Dhar Teacher Mohd Syed Dhar Lalbazar, Srinagar 82 17 Ishrat Aslam Teacher Mohd Aslam Khan Devi Angan, Srinagar 22.08.2014, the names of eligible Adhoc/ Contractual/ Consolidated employ- 83 18 Shaheen Nusrat Teacher Gh. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Catalogue Fair Timings

CATALOGUE Fair Timings 28 January 2016 Thursday Select Preview: 12 - 3pm By invitation Preview: 3 - 5pm By invitation Vernissage: 5 - 9pm IAF VIP Card holders (Last entry at 8.30pm) 29 - 30 January 2016 Friday and Saturday Business Hours: 11am - 2pm Public Hours: 2 - 8pm (Last entry at 7.30pm) 31 January 2016 Sunday Public Hours: 11am - 7pm (Last entry at 6.30pm) India Art Fair Team Director's Welcome Neha Kirpal Zain Masud Welcome to our 2016 edition of India Art Fair. Founding Director International Director Launched in 2008 and anticipating its most rigorous edition to date Amrita Kaur Srijon Bhattacharya with an exciting programme reflecting the diversity of the arts in Associate Fair Director Director - Marketing India and the region, India Art Fair has become South Asia's premier and Brand Development platform for showcasing modern and contemporary art. For our 2016 Noelle Kadar edition, we are delighted to present BMW as our presenting partner VIP Relations Director and JSW as our associate partner, along with continued patronage from our preview partner, Panerai. Saheba Sodhi Vishal Saluja Building on its success over the past seven years, India Art Senior Manager - Marketing General Manager - Finance Fair presents a refreshed, curatorial approach to its exhibitor and Alliances and Operations programming with new and returning international participants Isha Kataria Mankiran Kaur Dhillon alongside the best programmes from the subcontinent. Galleries, Vip Relations Manager Programming and Client Relations will feature leading Indian and international exhibitors presenting both modern and contemporary group shows emphasising diverse and quality content. Focus will present select galleries and Tanya Singhal Wol Balston organisations showing the works of solo artists or themed exhibitions. -

Credentialed Staff JHHS

FacCode Name Degree Status_category DeptDiv HCGH Abbas , Syed Qasim MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Abdi , Tsion MD MPH Consulting Staff Medicine Gastroenterology HCGH Abernathy Jr, Thomas W MD Consulting Staff Medicine Gastroenterology HCGH Aboderin , Olufunlola Modupe MD Contract Physician Pediatrics HCGH Adams , Melanie Little MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Adams , Scott McDowell MD Active Staff Orthopedic Surgery HCGH Adkins , Lisa Lister CRNP Nurse Practitioner Medicine HCGH Afzal , Melinda Elisa DO Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Agbor-Enoh , Sean MD PhD Active Staff Medicine Pulmonary Disease & Critical Care Medicine HCGH Agcaoili , Cecily Marie L MD Affiliate Staff Medicine HCGH Aggarwal , Sanjay Kumar MD Active Staff Pediatrics HCGH Aguilar , Antonio PA-C Physician Assistant Emergency Medicine HCGH Ahad , Ahmad Waqas MBBS Active Staff Surgery General Surgery HCGH Ahmar , Corinne Abdallah MD Active Staff Medicine HCGH Ahmed , Mohammed Shafeeq MD MBA Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Ahn , Edward Sanghoon MD Courtesy Staff Surgery Neurosurgery HCGH Ahn , Hyo S MD Consulting Staff Diagnostic Imaging HCGH Ahn , Sungkee S MD Active Staff Diagnostic Imaging HCGH Ahuja , Kanwaljit Singh MD Consulting Staff Medicine Neurology HCGH Ahuja , Sarina MD Consulting Staff Medicine HCGH Aina , Abimbola MD Active Staff Obstetrics and Gynecology HCGH Ajayi , Tokunbo Opeyemi MD Active Staff Medicine Internal Medicine HCGH Akenroye , Ayobami Tolulope MBChB MPH Active Staff Medicine Internal Medicine HCGH Akhter , Mahbuba -

AAR Part 1.Cdr

lumni ANNUAL REPORT 2010-11 An Initiative of the Institutional Development (ID) Program Office of Alumni Affairs and International Relations Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur Kharagpur - 721 302 IIT Kharagpur Institutional Development (ID) Program Editorial Group Patron : Prof. Amit Patra, Dean, AA&IR Chinna Boddipalli, Managing Director, ID Program Content Development: Shreyoshi Ghosh Corporate Communication Executive Idea Creation: Chinna Boddipalli Shreyoshi Ghosh Contributors' Data: Shampa Goswami Sadhan Banerjee Financial Reporting: Shampa Goswami Prasenjit Banerjee Published by: Office of Alumni Affairs and International Relations, IIT Kharagpur, Pin-721302 Ph: +91 3222 282236 Email: [email protected] Web: www.iitkgp.org Design and Printed by: Cygnus Advertising (India) Pvt. Ltd. 55B, Mirza Ghalib Street, 8th Floor, Saberwal House Kolkata - 700 016, West Bengal, India Phone : +91-33-3028 1737, Tele Fax : +91 03 22271528 Website : www.cygnusadvertising.in © IIT Kharagpur All Rights Reserved Contents: Message from Prof. Amit Patra, Dean, AA&IR 1 Diamond Jubilee in View of Director, Prof. Damodar Acharya 2 Progress Report of ID Program by Chinna Boddipalli 8 Details of Advisors and Executive Advisors of ID Program 9 Financial Statements, 2010-2011 10 Year-wise List of Contributors 16 (Highlights: Leadership Gifts, Major Gifts and Sponsorships, Annual Premium Contributors, Featured Donors, Campaign Contributors) Other Contributors over the years 40 IIT Foundation India Contributors' List 44 IIT Foundation USA Contributors' -

Dhfl Uncontactable Public Depo

Dewan Housing Finance Limited Pending Form CAs Important Notice for the Public Depositors with missing contact details For the FD holders having the Cust IDs listed below, it is requested to provide your e-mail id and contact number to complete the basic data in company records. The FD holders shall visit the nearest DHFL branch with below mentioned documents to update the contact details: 1. Self attested PAN card copy. 2. Duly signed form for contact details updating. The form is will be available at the DHFL branch offices Please note, it is important to file the Form CA and update your contact details as the earliest so that you aware of the development in the CIRP activities and can participate in the eVoting actives post every CoC. *We have tried contacting the below mentioned Public Depositors through the communication details available in the company records Customer ID Branch Customer Name 1558499 Chennai A Dhanasekar 1331296 Chennai A Kuppusamy 919868 Salem A Mohan 34010 Madurai A Sathiah 34884 Mangaluru A c subbegowda 10003986 Chennai A DEVA STELLA ANANTHI 10081442 Surat A K Diam 9004752 Rpu Dahisar A K ROY KARMAKAR 10111531 Trichy A Kavitha 1513463 Hyderabad A N Chidamber 10109799 Chennai A P Sanmugham 10108795 Trichy A Sakthivel 10024905 Gurgaon A U INCORP 1350646 Madurai A V Sreedharan 33884 Indore Aalok Garg 10087874 Thane Aarati Malhotra 10085709 Noida Aarti Khanna 1464682 Chennai Aarti Manoharlal Bijlani 10097692 Gurgaon Aayushi Saini 884459 Pune Aban H Bhandari 10108314 Surat Abbaskha Ismailkha Pathan 598025 Jaipur-Vaishali -

Revised Syllabus for Sem III and Sem IV Program: MA

AC / /2017 Item no. UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Revised Syllabus for Sem III and Sem IV Program: M.A. Course: History and Archaeology (Choice Based Credit System with effect from the Academic year 2017-2018 MA Degree Program – The Structure Semester III: Five Groups of Elective courses from parent Department Semester IV: Three Groups of Elective Courses from parent Department ------------------------------------------------------------ SYLLABUS SEMESTER – III List of Courses Elective Group I: A. History of Art and Architecture in Early India B. History of Art in Medieval India C. History of Architecture in Medieval India D. History of Art in Modern India E. History of Architecture in Modern India F. History, Culture and Heritage of Mumbai (1850 CE – 1990 CE) G. History of Tribal Art and Literature H. History of Indian Cinema and Social Realities I. History of Travel and Tourism in India J. History of Buddhism K. Philosophy of Buddhism L. History of Jainism M. History of Sufism in India Elective Group II: A. History of Indian Archaeology B. History of Travelogues in Ancient and Medieval India C. History of India‟s Maritime Heritage (16th and 17th Centuries) D. History of Labour and Entrepreneurship in India (1830 CE – 2000 CE) E. History of Science and Technology in Modern India 2 F. Environmental History of India (19th - 20th Centuries) G. History of Indian Diaspora H. History of Modern Warfare I. History of War and Society in 20th Century India J. Historical Perspectives on India‟s Foreign Policy Elective Group III: A. Builders of Modern India B. Indian National Movement (1857 CE to 1947 CE) C. -

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21St Century

Bollywood and Postmodernism Popular Indian Cinema in the 21st Century Neelam Sidhar Wright For my parents, Kiran and Sharda In memory of Rameshwar Dutt Sidhar © Neelam Sidhar Wright, 2015 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 9634 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9635 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0356 6 (epub) The right of Neelam Sidhar Wright to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Contents Acknowledgements vi List of Figures vii List of Abbreviations of Film Titles viii 1 Introduction: The Bollywood Eclipse 1 2 Anti-Bollywood: Traditional Modes of Studying Indian Cinema 21 3 Pedagogic Practices and Newer Approaches to Contemporary Bollywood Cinema 46 4 Postmodernism and India 63 5 Postmodern Bollywood 79 6 Indian Cinema: A History of Repetition 128 7 Contemporary Bollywood Remakes 148 8 Conclusion: A Bollywood Renaissance? 190 Bibliography 201 List of Additional Reading 213 Appendix: Popular Indian Film Remakes 215 Filmography 220 Index 225 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the following people for all their support, guidance, feedback and encouragement throughout the course of researching and writing this book: Richard Murphy, Thomas Austin, Andy Medhurst, Sue Thornham, Shohini Chaudhuri, Margaret Reynolds, Steve Jones, Sharif Mowlabocus, the D.Phil. -

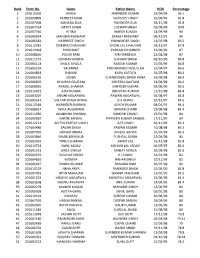

Rank Form No. Name Father Name DOB Percentage 1 201610302

Rank Form No. Name Father Name DOB Percentage 1 201610302 AKASH NARINDER KUMAR 18/04/98 93.1 2 201603899 PARNEET KAUR SUKHDEV SINGH 16/09/99 92.8 3 201607008 SANJANA DUA RAVINDER DUA 28/11/98 91.8 4 201607754 JAPJOT SINGH LOCHAN SINGH 03/09/98 90.8 5 201607746 HITIKA HARISH KUMAR 14/09/98 90 6 201606954 MAHIMA RASWANT SANJAY RASWANT 09/12/97 90 7 201606581 HARPREET SINGH PARWINDER SINGH 11/07/98 89.2 8 201612381 DHEERAJ CHAUHAN CHUNI LAL CHAUHAN 03/12/97 87.8 9 201614018 PARSHANT PARKASH CHANDER 22/09/99 87 10 201608260 POOJA RANI MR NARSINGH 25/02/98 87 11 201611575 GOURAV HOODA SUKHBIR SINGH 09/10/96 86.8 12 201604114 SHALU SINGLA RAKESH KUMAR 15/02/99 86.8 13 201605259 SALMANA MOHAMMED FAZLULLAH 15/04/97 86.6 14 201604864 SHIVANI KAPIL KATOCH 31/07/98 86.4 15 201606226 SONIA CHANDERHAS SINGH RANA 29/09/98 86.4 16 201606870 DHAIRYA GAUTAM DHEERAJ GAUTAM 24/04/98 86.2 17 201608065 ANMOL SHARMA SANTOSH KUMAR 02/06/99 85.6 18 201610031 AJAY KUMAR BHUSHAN KUMAR 11/10/98 84.8 19 201603207 SAKSHI AGGARWAL PAWAN AGGARWAL 01/08/97 84.8 20 201602541 SULTAN SINGH ATWAL G S ATWAL 20/12/97 84.6 21 201612584 NARINDER SHARMA ASHOK KUMAR 08/01/97 84.4 22 201608951 TANIA AGGARWAL ISHWAR CHAND 29/09/98 84.4 23 201611690 AKANKSHA SHARMA RAMESH CHAND 19/01/98 84 24 201600987 KARTIK SANDAL PARVEEN KUMAR SANDAL 17/11/97 84 25 201612211 ADITYA PARTAP SINGH AJIT SINGH 26/11/99 83.4 26 201603486 SAGAR SINGH PAWAN KUMAR 10/08/98 83.3 27 201607050 VRINDA ARORA DINESH ARORA 10/07/99 83.2 28 201603846 SWARLEEN KAUR PUSHPAL SINGH 22/04/98 83 29 201602959 TANUJ SHARMA -

The South Asian Art Market Report 2017

The South Asian Art Market Report 2017 ° Colombo The South Asian Art Market Report 2017 INTRODUCTION It’s 10 years ago since we published our first art market report Yes, the South Asian art market still lacks government support on the South Asian art market, predominantly focusing on India, compared to other Asian art markets (China’s for instance), but and I am very excited to see a market that is in a new, and I private foundations are gradually filling the vacuum. What the would argue, much healthier cycle. Samdani Art Foundation in Dhaka has managed to achieve with the Dhaka Art Summit is a great example. The South Asian art The South Asian art market boom between 2004 and 2008 market needs more champions like this, and with South Asian was exciting, because it made this regional art market gain economies being among the fastest growing in the world, the proper international attention for the first time, and laid the requisite private wealth would appear available to support it. foundation for much of the contemporary gallery, art fair and I am very excited to publish this report after 10 years of auction infrastructure we see today. However, there was also monitoring and following this market as, for the first time since a destructive side to these boom years, felt shortly after the 2008, I sense a different type of optimism. Unlike the sheer financial crisis in 2009, when the top 3 auction houses market euphoria of 2008, this is something more tangible; recorded a 66% drop in sales of modern and South Asian biennials and festivals are getting more contemporary art and the share of contemporary international attention; initiatives are being set art dropped from 41% in 2008 to 12% in 2009; up to support artists and artistic exchange; and the dangers of speculation were manifested. -

Social Science TABLE of CONTENTS

2015 Social Science TABLE OF CONTENTS Academic Tools 79 Labour Economics 71 Agrarian Studies & Agriculture 60 Law & Justice 53 Communication & Media Studies 74-78 Literature 13-14 Counselling & Psychotherapy 84 7LHJL *VUÅPJ[:[\KPLZ 44-48 Criminology 49 Philosophy 24 Cultural Studies 9-13 Policy Studies 43 Dalit Sociology 8 Politics & International Relations 31-42 Development Communication 78 Psychology 80-84 Development Studies 69-70 Research Methods 94-95 Economic & Development Studies 61-69 SAGE Classics 22-23 Education 89-92 SAGE Impact 72-74 Environment Studies 58-59 SAGE Law 51-53 Family Studies 88 SAGE Studies in India’s North East 54-55 Film & Theatre Studies 15-18 Social Work 92-93 Gender Studies 19-21 Sociology & Social Theory 1-7 Governance 50 Special Education 88 Health & Nursing 85-87 Sport Studies 71 History 25-30 Urban Studies 56-57 Information Security Management 71 Water Management 59 Journalism 79 Index 96-100 SOCIOLOGY & SOCIAL THEORY HINDUISM IN INDIA A MOVING FAITH Modern and Contemporary Movements Mega Churches Go South Edited by Will Sweetman and Aditya Malik Edited by Jonathan D James Edith Cowan University, Perth Hinduism in India is a major contribution towards ongoing debates on the nature and history of the religion In A Moving Faith by Dr Jonathan James, we see for in India. Taking into account the global impact and the first time in a single coherent volume, not only that influence of Hindu movements, gathering momentum global Christianity in the mega church is on the rise, even outside of India, the emphasis is on Hinduism but in a concrete way, we are able to observe in detail as it arose and developed in sub-continent itself – an what this looks like across a wide variety of locations, approach which facilitates greater attention to detail cultures, and habitus. -

Rtisal612.Txt

June 2012 +‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+ |empcode |empname |gross | +‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐+ | 15017|S.N. SINGH | 135630.000| | 15018|SUHAIL AHMED | 143574.000| | 15021|D.K. SEHGAL | 146987.000| | 15027|V.S. BISARIA | 130350.000| | 15028|G.P. AGARWAL | 136430.000| | 15031|SAROJ MISHRA | 132297.000| | 15032|P.K. ROYCHOUDHURY | 117018.000| | 15033|SUNIL NATH | 122298.000| | 15034|ASHOK KUMAR SRIVASTAVA | 122298.000| | 15038|SUDHIR CHANDRA | 131852.000| | 15039|RAJENDAR BAHL | 135630.000| | 15040|B.S. PANWAR | 128156.000| | 15041|SHIBAN KISHEN KOUL | 136630.000| | 15045|SUNEET TULI | 117216.000| | 15049|G. JAYARAMAN | 135630.000| | 15050|S.K. DUBE | 135630.000| | 15051|OM PRAKASH SHARMA | 126572.000| | 15053|U.C. MOHANTY | 150630.000| | 15055|MAITHILI SHARAN | 145350.000| | 15057|PRAMILA GOEL | 122298.000| | 15059|R.C. RAGHAVA | 113388.000| | 15060|H.C. UPADHYAYA | 105903.000| | 15061|A.D. RAO | 125186.000| | 15062|POORNIMA AGARWAL | 113388.000| | 15064|NIVEDITA KARMAKAR GOHIL | 108356.000| | 15065|MANJU MOHAN | 122298.000| | 15076|SUSHIL KUMAR DASH | 128156.000| | 15080|SNEH ANAND | 135630.000| | 15081|ALOK RANJAN RAY | 155630.000| | 15083|HARPAL SINGH | 122298.000| | 15084|S.M.K. RAHMAN | 97556.000| | 15090|M.N. GUPTA | 135630.000| | 15091|A.K. SINGH | 155391.000| | 15095|P.S. PANDEY | 117117.000| | 15103|H.M. CHAWLA | 135630.000| | 15104|RAM NATH RAM | 120434.000| | 15105|T.S.BHATTI | 122298.000| | 15107|SRIRAM HEGDE | 108356.000| | 15127|SURINDRA PRASAD | 150630.000| | 15136|VINOD CHANDRA | 135630.000| | 15137|R.K. PATNEY | 135630.000| | 15139|BASABI BHAUMIK | 135630.000| | 15142|G.S. VISWESWARAN | 135630.000| | 15144|UMESH KUMAR | 113388.000| | 15145|P.R. BIJWE | 135350.000| | 15146|V.K.