Theory and Interpretation of Narrative James Phelan, Peter J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Non-Binary Speech, Race, and Non-Normative Gender

Non-binary speech, race, and non-normative gender: Sociolinguistic style beyond the binary Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ariana June Steele, B.A. Linguistics Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2019 Thesis Committee: Kathryn Campbell-Kibler, Adviser Cynthia Clopper i Copyright by Ariana June Steele 2019 ii Abstract Non-binary speech is understudied in the realm of sociolinguistics. Previous studies on non- binary speech (Kirtley 2015; Gratton 2016; Jas 2018) suggest that non-binary speakers are able to make use of linguistic variables that have been tied to binary gender in novel ways, often dependent on social context and goals, though these studies are limited in scope, considering eight or feWer non-binary talkers in their studies. Research into sociolinguistic style (Eckert 2008; Campbell-Kibler 2011) emphasiZes the ways that multiple linguistic and extralinguistic variables can be employed simultaneously to construct coherent styles, leaving room for speaker race to be included in the stylistic context (Pharao et al. 2014). Zimman’s (2017) study on transmasculine speakers showed that speakers can employ binary gendered linguistic variables in speech styles to position themselves towards or against normative binary gender. The current study considers how tWenty non-binary speakers, stratified by sex assigned at birth and race, use /s/ and f0, variables which tied to gender in previous research, alongside clothing to construct non-binary gendered styles. Results further support that race is an important construct in understanding gendered speech, as Black non-binary speakers produce /s/ differently with respect to self-identified masculinity than do white non-binary speakers. -

Mobb Deep Reveal Tracklist for the Black Cocaine EP Featuresnas

Mobb Deep Reveal Tracklist For “The Black Cocaine” EP, Features Nas ERROR_GETTING_IMAGES-1 Mobb Deep Reveal Tracklist For “The Black Cocaine” EP, Features Nas 1 / 4 2 / 4 See separate feature article on page three for more on the ... country club feature. 60 Rider ... ing call for the show's 27th season outside of Tommy Doyle's in ... albums that any hip-hop fan must ... “Mobb Deep : The Black Cocaine. EP.” The album will be released on ... cord with Nas making a guest appear-.. Eight tracks deep, Lil' Fame and Billy Danze are sporting their usual energetic ... The EP was released shortly before their third album, "First Family 4 Life", ... Exactly one month from today, Mobb Deep will be releasing their first project ... and guest features and production from the usual suspects like Nas, ... Plus, it's a soundtrack, and hip-hop soundtracks have a history of mediocrity. ... Drumma Boy-produced album opener “Smokin On” featuring Juicy J sets the ... The classic status of Mobb Deep's The Infamous is undisputed: It's a seminal ... If the Black Cocaine EP released last week is any indication, the .... ... -show-featuring-rockie-fresh-julian-malone-harry-fraud-plastician- and-more-video/ ... http://www.jayforce.com/rb/vinyl-destination-ep-19-vancouver-canada-thats-a-wrap- ... 0.2 http://www.jayforce.com/music/dj-spintelect-the-best-of-nas-mixtape/ ... .jayforce.com/videos/mobb-deep-20th-anniversary- show-in-chicago-video/ .... Mobb Deep Reveal Tracklist For "The Black Cocaine" EP, Features Nas. 169. Mobb Deep has announced an upcoming EP to be released on ... -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

RTM 360 | Michigan Chronicle | 2019 Media Kit CONTENTS Page No

RTM 360 | Michigan Chronicle | 2019 Media Kit CONTENTS Page No ABOUT US 3 - 4 OUR AUDIENCE 5 - 6 PRODUCTS AND SERVICES 7 - 15 • PRINT 8 • TARGETED BANNER & VIDEO MARKETING 9 • EMAIL MARKETING 10 • TARGETED EMAIL 11 • E-NEWS DAILY 12 • NATIONAL SWEEPSTAKES AND CONTESTS 13 • SOCIAL MEDIA 14 • BRANDED PROJECTS 15 • BRANDED EVENTS 16 • RTM360 17 EDITORIAL AND EVENTS CALENDAR 18 – 20 • QUARTERS 1 & 2 19 • QUARTERS 3 & 4 20 RATES & SPECIFICATIONS 21 – 27 • CIRCULATION 22 • DISPLAY RATES 23 • DIGITAL & PACKAGES 24 • CLASSIFIED RATES 25 • INSERT RATES 26 • AD SPECS 27 RTM 360 | Michigan Chronicle | 2019 Media Kit Media Kit| 21 -- 2 A B O U T U S Real Times Media (RTM) is a Detroit-based multimedia company with a legacy that stretches back over 100 years. As the parent company to five of the country’s most respected African American-owned news organizations, the Atlanta Daily World, Atlanta Tribune: The Magazine, the Chicago Defender, the Michigan Chronicle, and the New Pittsburgh Courier, it is our job to maintain the heartbeat of the African American voice. Being built on the foundation of historic brands affords RTM a depth of knowledge and assets that are multi-generational, relevant, and trustworthy. RTM has an ongoing commitment to delivering quality news, events, and entertainment for African American audiences. In addition to its news brands, RTM offers custom programming and niche publishing through Who’s Who In Black—a professional lifestyle brand focused on live and virtual business/social events and content; strategic communications consultancy services through its marketing services arm, RTM360°, and RTM Digital Studios, an unparalleled archive of historical photographs, videos, and film clips of the African American experience available through licensing for advertising, marketing, publishing, and film initiatives. -

On the Rise and Decline of Wulitou 无厘头's Popularity in China

The Act of Seeing and the Narrative: On the Rise and Decline of Wulitou 无厘头’s Popularity in China Inaugural dissertation to complete the doctorate from the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne in the subject Chinese Studies presented by Wen Zhang ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks go to my supervisors, Prof. Dr. Stefan Kramer, Prof. Dr. Weiping Huang, and Prof. Dr. Brigitte Weingart for their support and encouragement. Also to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne for providing me with the opportunity to undertake this research. Last but not least, I want to thank my friends Thorsten Krämer, James Pastouna and Hung-min Krämer for reviewing this dissertation and for their valuable comments. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 0.1 Wulitou as a Popular Style of Narrative in China ........................................................... 1 0.2 Story, Narrative and Schema ................................................................................................. 3 0.3 The Deconstruction of Schema in Wulitou Narratives ................................................... 5 0.4 The Act of Seeing and the Construction of Narrative .................................................... 7 0.5 The Rise of the Internet and Wulitou Narrative .............................................................. 8 0.6 Wulitou Narrative and Chinese Native Cultural Context .......................................... -

News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive?

NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? PENELOPE MUSE ABERNATHY Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics Will Local News Survive? | 1 NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? By Penelope Muse Abernathy Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media School of Media and Journalism University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2 | Will Local News Survive? Published by the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media with funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of the Provost. Distributed by the University of North Carolina Press 11 South Boundary Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514-3808 uncpress.org Will Local News Survive? | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 5 The News Landscape in 2020: Transformed and Diminished 7 Vanishing Newspapers 11 Vanishing Readers and Journalists 21 The New Media Giants 31 Entrepreneurial Stalwarts and Start-Ups 40 The News Landscape of the Future: Transformed...and Renewed? 55 Journalistic Mission: The Challenges and Opportunities for Ethnic Media 58 Emblems of Change in a Southern City 63 Business Model: A Bigger Role for Public Broadcasting 67 Technological Capabilities: The Algorithm as Editor 72 Policies and Regulations: The State of Play 77 The Path Forward: Reinventing Local News 90 Rate Your Local News 93 Citations 95 Methodology 114 Additional Resources 120 Contributors 121 4 | Will Local News Survive? PREFACE he paradox of the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing economic shutdown is that it has exposed the deep Tfissures that have stealthily undermined the health of local journalism in recent years, while also reminding us of how important timely and credible local news and information are to our health and that of our community. -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

Doctor Strange Comics As Post-Fantasy

Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Karen Swenson, Chair Nancy A. Metz Katrina M. Powell April 15, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Fantasy, Comics Studies, Postmodernism, Post-Fantasy Copyright 2019, Jessie L. Rogers Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers (ABSTRACT) This thesis demonstrates that Doctor Strange comics incorporate established tropes of the fantastic canon while also incorporating postmodern techniques that modernize the genre. Strange’s debut series, Strange Tales, begins this development of stylistic changes, but it still relies heavily on standard uses of the fantastic. The 2015 series, Doctor Strange, builds on the evolution of the fantastic apparent in its predecessor while evidencing an even stronger presence of the postmodern. Such use of postmodern strategies disrupts the suspension of disbelief on which popular fantasy often relies. To show this disruption and its effects, this thesis examines Strange Tales and Doctor Strange (2015) as they relate to the fantastic cornerstones of Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and Rowling’s Harry Potter series. It begins by defining the genre of fantasy and the tenets of postmodernism, then it combines these definitions to explain the new genre of postmodern fantasy, or post-fantasy, which Doctor Strange comics develop. To show how these comics evolve the fantasy genre through applications of postmodernism, this thesis examines their use of otherworldliness and supernaturalism, as well as their characterization and narrative strategies, examining how these facets subvert our expectations of fantasy texts. -

Continuity in Color: the Persistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2016 Continuity in Color: The eP rsistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes McKinley May Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation May, McKinley, "Continuity in Color: The eP rsistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes" (2016). University Honors Program Theses. 170. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/170 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Continuity in Color: The Persistence of Symbolic Meaning in Myths, Tales, and Tropes An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Literature and Philosophy. By McKinley May Under the mentorship of Joe Pellegrino ABSTRACT This paper examines the symbolism of the colors black, white, and red from ancient times to modern. It explores ancient myths, the Grimm canon of fairy tales, and modern film and television tropes in order to establish the continuity of certain symbolisms through time. In regards to the fairy tales, the examination focuses solely on the lesser-known stories, due to the large amounts of scholarship surrounding the “popular” tales. The continuity of interpretation of these three major colors (black, white, and red) establishes the link between the past and the present and demonstrates the influence of older myths and beliefs on modern understandings of the colors. -

Post-Postfeminism?: New Feminist Visibilities in Postfeminist Times

FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 16, NO. 4, 610–630 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2016.1193293 Post-postfeminism?: new feminist visibilities in postfeminist times Rosalind Gill Department of Sociology, City University, London, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article contributes to debates about the value and utility Postfeminism; neoliberalism; of the notion of postfeminism for a seemingly “new” moment feminism; media magazines marked by a resurgence of interest in feminism in the media and among young women. The paper reviews current understandings of postfeminism and criticisms of the term’s failure to speak to or connect with contemporary feminism. It offers a defence of the continued importance of a critical notion of postfeminism, used as an analytical category to capture a distinctive contradictory-but- patterned sensibility intimately connected to neoliberalism. The paper raises questions about the meaning of the apparent new visibility of feminism and highlights the multiplicity of different feminisms currently circulating in mainstream media culture—which exist in tension with each other. I argue for the importance of being able to “think together” the rise of popular feminism alongside and in tandem with intensified misogyny. I further show how a postfeminist sensibility informs even those media productions that ostensibly celebrate the new feminism. Ultimately, the paper argues that claims that we have moved “beyond” postfeminism are (sadly) premature, and the notion still has much to offer feminist cultural critics. Introduction: feminism, postfeminism and generation On October 2, 2015 the London Evening Standard (ES) published its first glossy magazine of the new academic year. With a striking red, white, and black cover design it showed model Neelam Gill in a bright red coat, upon which the words “NEW (GEN) FEM” were superimposed in bold. -

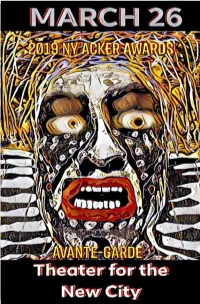

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

Gay Ghetto Comics and the Alternative Gay Comics of Robert Kirby

Title Gay Ghetto comics and the alternative gay comics of Robert Kirby Type Article URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/10784/ Dat e 2 0 1 7 Citation Shamsavari, Sina (2017) Gay Ghetto comics and the alternative gay comics of Robert Kirby. Queer Studies in Media and Popular Culture, 2 (1). pp. 95-117. ISSN 2055- 5 7 0 9 Cr e a to rs Shamsavari, Sina Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Gay Ghetto comics and the alternative gay comics of Robert Kirby Sina Shamsavari, London College of Fashion Abstract This article focuses on North American gay comics, especially the ‘gay ghetto’ sub-genre, and on the alternative gay comics that have been created in response to the genre’s conventions. Gay comics have received little scholarly attention and this article attempts to begin redressing this balance, as well as turning attention to the contrasts between different genres within the field of gay comics. Gay ghetto comics and cartoons construct a dominant gay habitus, representing the gay community as relatively stable and unified, while the alternative gay male comics discussed critique the dominant gay habitus and construct instead an alternative gay – or ‘queer’ – habitus. The article focuses on the work on Robert Kirby, an influential cartoonist and editor of gay comics anthologies, and particularly on his story ‘Private Club’, in order to explore some of the typical themes and concerns of alternative gay ghetto comics.