Migration and Society in Gilgit, Northem Areas Ofpakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

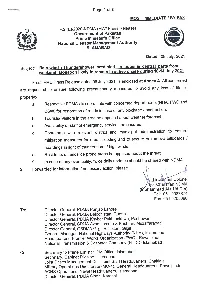

08 July 2021, Is Enclosed at Annex A

Page 1 of3 MOST IMMEDIATE/BY FAX F.2 (E)/2020-NDMA (MW/ Press Release) Government of Pakistan Prime Minister's Office National Disaster Management Authority ISLAMABAD NDMA Dated: 08 July, 2021 Subject: Rain-wind / Thundershower predicted in upper & central parts from weekend (Monsoon likely to remain in active phase during 10-14 July 2021 concerned Fresh PMD Press Release dated 08 July 2021, is enclosed at Annex A. All measures to avoid any loss of life or are requested to ensure following precautionary property: FWO and a. Respective PDMAs to coordinate with concerned departments (NHA, obstruction. C&W) for restoration of roads in case of any blockage/ . Tourists/Visitors in the area be apprised about weather forecast C. Availability of staff of emergency services be ensured. Coordinate with relevant district and municipal administration to ensure d. mitigation measures for urban flooding and to secure or remove billboards/ hoardings in light of thunderstorm/ high winds the threat. e. Residents of landslide prone areas be apprised about In case of any eventuality, twice daily updates should be shared with NDMA. f. 2 Forwarded for information / necessary action, please. Lieutenant Colonel For Chainman NDMA (Muhammad Ala Ud Din) Tel: 051-9087874 Fax: 051 9205086 To Director General, PDMA Punjab Lahore Director General, PDMA Balochistan, Quetta Director General, PDMA Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Peshawar Director General, SDMA Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Muzaffarabad Director General, GBDMA Gilgit Baltistan, Gilgit General Manager, National Highways Authority -

Politics of Nawwab Gurmani

Politics of Accession in the Undivided India: A Case Study of Nawwab Mushtaq Gurmani’s Role in the Accession of the Bahawalpur State to Pakistan Pir Bukhsh Soomro ∗ Before analyzing the role of Mushtaq Ahmad Gurmani in the affairs of Bahawalpur, it will be appropriate to briefly outline the origins of the state, one of the oldest in the region. After the death of Al-Mustansar Bi’llah, the caliph of Egypt, his descendants for four generations from Sultan Yasin to Shah Muzammil remained in Egypt. But Shah Muzammil’s son Sultan Ahmad II left the country between l366-70 in the reign of Abu al- Fath Mumtadid Bi’llah Abu Bakr, the sixth ‘Abbasid caliph of Egypt, 1 and came to Sind. 2 He was succeeded by his son, Abu Nasir, followed by Abu Qahir 3 and Amir Muhammad Channi. Channi was a very competent person. When Prince Murad Bakhsh, son of the Mughal emperor Akbar, came to Multan, 4 he appreciated his services, and awarded him the mansab of “Panj Hazari”5 and bestowed on him a large jagir . Channi was survived by his two sons, Muhammad Mahdi and Da’ud Khan. Mahdi died ∗ Lecturer in History, Government Post-Graduate College for Boys, Dera Ghazi Khan. 1 Punjab States Gazetteers , Vol. XXXVI, A. Bahawalpur State 1904 (Lahore: Civil Military Gazette, 1908), p.48. 2 Ibid . 3 Ibid . 4 Ibid ., p.49. 5 Ibid . 102 Pakistan Journal of History & Culture, Vol.XXV/2 (2004) after a short reign, and confusion and conflict followed. The two claimants to the jagir were Kalhora, son of Muhammad Mahdi Khan and Amir Da’ud Khan I. -

Deforestation in the Princely State of Dir on the North-West Frontier and the Imperial Strategy of British India

Central Asia Journal No. 86, Summer 2020 CONSERVATION OR IMPLICIT DESTRUCTION: DEFORESTATION IN THE PRINCELY STATE OF DIR ON THE NORTH-WEST FRONTIER AND THE IMPERIAL STRATEGY OF BRITISH INDIA Saeeda & Khalil ur Rehman Abstract The Czarist Empire during the nineteenth century emerged on the scene as a Eurasian colonial power challenging British supremacy, especially in Central Asia. The trans-continental Russian expansion and the ensuing influence were on the march as a result of the increase in the territory controlled by Imperial Russia. Inevitably, the Russian advances in the Caucasus and Central Asia were increasingly perceived by the British as a strategic threat to the interests of the British Indian Empire. These geo- political and geo-strategic developments enhanced the importance of Afghanistan in the British perception as a first line of defense against the advancing Russians and the threat of presumed invasion of British India. Moreover, a mix of these developments also had an impact on the British strategic perception that now viewed the defense of the North-West Frontier as a vital interest for the security of British India. The strategic imperative was to deter the Czarist Empire from having any direct contact with the conquered subjects, especially the North Indian Muslims. An operational expression of this policy gradually unfolded when the Princely State of Dir was loosely incorporated, but quite not settled, into the formal framework of the imperial structure of British India. The elements of this bilateral arrangement included the supply of arms and ammunition, subsidies and formal agreements regarding governance of the state. These agreements created enough time and space for the British to pursue colonial interests in Ph.D. -

Pdf 325,34 Kb

(Final Report) An analysis of lessons learnt and best practices, a review of selected biodiversity conservation and NRM projects from the mountain valleys of northern Pakistan. Faiz Ali Khan February, 2013 Contents About the report i Executive Summary ii Acronyms vi SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. The province 1 1.2 Overview of Natural Resources in KP Province 1 1.3. Threats to biodiversity 4 SECTION 2. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS (review of related projects) 5 2.1 Mountain Areas Conservancy Project 5 2.2 Pakistan Wetland Program 6 2.3 Improving Governance and Livelihoods through Natural Resource Management: Community-Based Management in Gilgit-Baltistan 7 2.4. Conservation of Habitats and Species of Global Significance in Arid and Semiarid Ecosystem of Baluchistan 7 2.5. Program for Mountain Areas Conservation 8 2.6 Value chain development of medicinal and aromatic plants, (HDOD), Malakand 9 2.7 Value Chain Development of Medicinal and Aromatic plants (NARSP), Swat 9 2.8 Kalam Integrated Development Project (KIDP), Swat 9 2.9 Siran Forest Development Project (SFDP), KP Province 10 2.10 Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) 10 2.11 Malakand Social Forestry Project (MSFP), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 11 2.12 Sarhad Rural Support Program (SRSP) 11 2.13 PATA Project (An Integrated Approach to Agriculture Development) 12 SECTION 3. MAJOR LESSONS LEARNT 13 3.1 Social mobilization and awareness 13 3.2 Use of traditional practises in Awareness programs 13 3.3 Spill-over effects 13 3.4 Conflicts Resolution 14 3.5 Flexibility and organizational approach 14 3.6 Empowerment 14 3.7 Consistency 14 3.8 Gender 14 3.9. -

Assessment of Spatial and Temporal Flow Variability of the Indus River

resources Article Assessment of Spatial and Temporal Flow Variability of the Indus River Muhammad Arfan 1,* , Jewell Lund 2, Daniyal Hassan 3 , Maaz Saleem 1 and Aftab Ahmad 1 1 USPCAS-W, MUET Sindh, Jamshoro 76090, Pakistan; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (A.A.) 2 Department of Geography, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +92-346770908 or +1-801-815-1679 Received: 26 April 2019; Accepted: 29 May 2019; Published: 31 May 2019 Abstract: Considerable controversy exists among researchers over the behavior of glaciers in the Upper Indus Basin (UIB) with regard to climate change. Glacier monitoring studies using the Geographic Information System (GIS) and remote sensing techniques have given rise to contradictory results for various reasons. This uncertain situation deserves a thorough examination of the statistical trends of temperature and streamflow at several gauging stations, rather than relying solely on climate projections. Planning for equitable distribution of water among provinces in Pakistan requires accurate estimation of future water resources under changing flow regimes. Due to climate change, hydrological parameters are changing significantly; consequently the pattern of flows are changing. The present study assesses spatial and temporal flow variability and identifies drought and flood periods using flow data from the Indus River. Trends and variations in river flows were investigated by applying the Mann-Kendall test and Sen’s method. We divide the annual water cycle into two six-month and four three-month seasons based on the local water cycle pattern. -

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’S Posture Toward Afghanistan Since 2001

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’s Posture toward Afghanistan since 2001 Since the terrorist at- tacks of September 11, 2001, Pakistan has pursued a seemingly incongruous course of action in Afghanistan. It has participated in the U.S. and interna- tional intervention in Afghanistan both by allying itself with the military cam- paign against the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida and by serving as the primary transit route for international military forces and matériel into Afghanistan.1 At the same time, the Pakistani security establishment has permitted much of the Afghan Taliban’s political leadership and many of its military command- ers to visit or reside in Pakistani urban centers. Why has Pakistan adopted this posture of Afghan Taliban accommodation despite its nominal participa- tion in the Afghanistan intervention and its public commitment to peace and stability in Afghanistan?2 This incongruence is all the more puzzling in light of the expansion of insurgent violence directed against Islamabad by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a coalition of militant organizations that are independent of the Afghan Taliban but that nonetheless possess social and po- litical links with Afghan cadres of the Taliban movement. With violence against Pakistan growing increasingly indiscriminate and costly, it remains un- clear why Islamabad has opted to accommodate the Afghan Taliban through- out the post-2001 period. Despite a considerable body of academic and journalistic literature on Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan since 2001, the subject of Pakistani accommodation of the Afghan Taliban remains largely unaddressed. Much of the existing literature identiªes Pakistan’s security competition with India as the exclusive or predominant driver of Pakistani policy vis-à-vis the Afghan Khalid Homayun Nadiri is a Ph.D. -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Pakistan in Areas

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CONFLICT-AFFECTED POPULATIONS IN PAKISTAN IN FY 2009 AND TO DATE IN FY 2010 Faizabad KEY TAJIKISTAN USAID/OFDA USAID/Pakistan USDA USAID/FFP State/PRM DoD Amu darya AAgriculture and Food Security S Livelihood Recovery PAKISTAN Assistance to Conflict-Affected y Local Food Purchase Populations ELogistics Economic Recovery ChitralChitral Kunar Nutrition Cand Market Systems F Protection r Education G ve Gilgit V ri l Risk Reduction a r Emergency Relief Supplies it a h Shelter and Settlements C e Food For Progress I Title II Food Assistance Shunji gol DHealth Gilgit Humanitarian Coordination JWater, Sanitation, and Hygiene B and Information Management 12/04/09 Indus FAFA N A NWFPNWFP Chilas NWFP AND FATA SEE INSET UpperUpper DirDir SwatSwat U.N. Agencies, E KohistanKohistan Mahmud-e B y Da Raqi NGOs AGCJI F Asadabad Charikar WFP Saidu KUNARKUNAR LowerLower ShanglaShangla BatagramBatagram GoP, NGOs, BajaurBajaur AgencyAgency DirDir Mingora l y VIJaKunar tro Con ImplementingMehtarlam Partners of ne CS A MalakandMalakand PaPa Li Î! MohmandMohmand Kabul Daggar MansehraMansehra UNHCR, ICRC Jalalabad AgencyAgency BunerBuner Ghalanai MardanMardan INDIA GoP e Cha Muzaffarabad Tithwal rsa Mardan dd GoP a a PeshawarPeshawar SwabiSwabi AbbottabadAbbottabad y enc Peshawar Ag Jamrud NowsheraNowshera HaripurHaripur AJKAJK Parachinar ber Khy Attock Punch Sadda OrakzaiOrakzai TribalTribal AreaArea Î! Adj.Adj. PeshawarPeshawar KurrumKurrum AgencyAgency Islamabad Gardez TribalTribal AreaArea AgencyAgency Kohat Adj.Adj. KohatKohat Rawalpindi HanguHangu Kotli AFGHANISTAN KohatKohat ISLAMABADISLAMABAD Thal Mangla reservoir TribalTribal AreaArea AdjacentAdjacent KarakKarak FATAFATA BannuBannu us Bannu Ind " WFP Humanitarian Hub NorthNorth WWaziristanaziristan BannuBannu SOURCE: WFP, 11/30/09 Bhimbar AgencyAgency SwatSwat" TribalTribal AreaArea " Adj.Adj. -

Survey of Ecotourism Potential in Pakistan's Biodiversity Project Area (Chitral and Northern Areas): Consultancy Report for IU

Survey of ecotourism potential in Pakistan’s biodiversity project area (Chitral and northern areas): Consultancy report for IUCN Pakistan John Mock and Kimberley O'Neil 1996 Keywords: conservation, development, biodiversity, ecotourism, trekking, environmental impacts, environmental degradation, deforestation, code of conduct, policies, Chitral, Pakistan. 1.0.0. Introduction In Pakistan, the National Tourism Policy and the National Conservation Strategy emphasize the crucial interdependence between tourism and the environment. Tourism has a significant impact upon the physical and social environment, while, at the same time, tourism's success depends on the continued well-being of the environment. Because the physical and social environment constitutes the resource base for tourism, tourism has a vested interest in conserving and strengthening this resource base. Hence, conserving and strengthening biodiversity can be said to hold the key to tourism's success. The interdependence between tourism and the environment is recognized worldwide. A recent survey by the Industry and Environment Office of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP/IE) shows that the resource most essential for the growth of tourism is the environment (UNEP 1995:7). Tourism is an environmentally-sensitive industry whose growth is dependent upon the quality of the environment. Tourism growth will cease when negative environmental effects diminish the tourism experience. By providing rural communities with the skills to manage the environment, the GEF/UNDP funded project "Maintaining Biodiversity in Pakistan with Rural Community Development" (Biodiversity Project), intends to involve local communities in tourism development. The Biodiversity Project also recognizes the potential need to involve private companies in the implementation of tourism plans (PC II:9). -

Renewable Energy Development Sector Investment Program, Project 3

Advance Contracting Notice Date: 21 November 2012 Country/Borrower: Islamic Republic of Pakistan Title of Proposed Project: Renewable Energy Development Sector Investment Program, Project 3 Name and Address of the Implementing Agency: Gilgit Baltistan Water and Power Overall Coordination Department Officer's Name: Engineer Ghulam Mehdi Position: Secretary Water & Power Gilgit-Baltistan Telephone: 05811-920306 Mobile: 0355-4110000, 0333-5571314 Email address [email protected], [email protected] Office Address: Office of the Secretary Water & Power Department Gilgit-Baltistan Gilgit Gilgit Baltistan Water and Power Shargarthang HPP Department Officer's Name: Syed Ijlal Hussain Position: Project Director Telephone: 92 5815-920241 Fax: 92 92-5815-920242 Mobile: 0345-9036497, 0301-2854543 Email address: [email protected] Office Address: Office of the Project Director 26 MW SHPP near Sher Ali Chowk Skardu Gilgit Baltistan Water and Power Chilas HPP Department Officer's Name: Abdul Khaliq Position: Project Director Telephone: 92 5812-450488 Fax: 92-5812-450486 Mobile: 0355-5134826, 0342-5257533 Email address: [email protected] Office Address: Office of the Project Director 04 MW Thak near DC Chowk Chilas Gilgit-Baltistan Brief Description of the Project: Part A – Clean Energy Development. Part A will construct two small- to medium-sized HPPs and associated distribution facilities in GB: (i) 26.6 MW Shagarthang HPP in Skardu; and (ii) 4 MW Chilas HPP in Chilas. Part B – Consultancy Services for Project Supervision, Feasibility Studies and Capacity Building. Part B will finance consultancy services for (i) tender design, preparation of bidding documents, supervision and management for construction of the Subprojects; (ii) conducting feasibilities studies for 4-5 new small to medium hydropower sites having aggregate 127 MW capacity; and (iii) capacity building and institutional strengthening for the provincial government who will be the executing and implementing agencies for the project. -

The Case of Diamerbhashadam in Pakistan

Sabir M., Torre A., 2017, Different proximities and conflicts related to the setting of big infrastructures. The case of Diamer Basha Dam in Pakistan, in Bandyopadhyay S., Torre A., Casaca P., Dentinho T. (eds.), 2017, Regional Cooperation in South Asia. Socio-economic, Spatial, Ecological and Institu- tional Aspects, Springer, 363 p. Different Proximities and Conflicts Related to the Setting of Big Infrastructures: The Case of DiamerBhashaDam in Pakistan Muazzam Sabir and André Torre UMR SAD-APT, INRA – Agroparistech, University Paris Saclay, France. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Land use conflicts are recognized as the result of mismanagement of infrastructural development projects. Several issues have been conferred related to infrastructural projects in Asia and South Asia, like corruption, mismanagement, cronyism and adverse socioeconomic impacts. The paper focuses particularly on land use conflicts related to Diamer-Bhasha dam project in northern Pakistan. Keeping in view this peculiar case, it goes into the concept of conflicts and proxim- ity, e.g. types of proximity and the role they play in conflict generation, conflict resolution and modes of conflict prevention. We provide the different types and expressions of conflicts due to Diamer-Bhasha dam project, their impact on local population and the territory, e.g. unfair land acquisition, improper displacement, compensation, resettlement and livelihood issues. Contiguity problems due to geo- graphical proximity as well as mechanisms of conflict resolution through organized proximity are also discussed. Finally, we conclude and recommend the strategies for better governance and the way ahead for upcoming studies on similar issues. 16.1 Introduction Land due to infrastructural projects has been subject to conflicts in several parts of the world and greatly influenced the socioeconomic position of different actors (Oppio et al. -

Monthly Weather Report April 2019

Monthly Weather Report April 2019 Director General Pakistan Meteorological Department Prepared by: National Weather Forecasting Center Islamabad Contents SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 FIRST SPELL ................................................................................................................................... 3 SECOND SPELL ................................................................................................................................ 5 THIRD SPELL .................................................................................................................................. 7 FOURTH SPELL ............................................................................................................................... 9 ACCUMULATIVE RAINFALL ......................................................................................................... 11 FORECAST VALIDATION ............................................................................................................... 13 TEMPERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 14 DROUGHT CONDITION ................................................................................................................. -

Pakistan-Afghanistan Relations from 1978 to 2001: an Analysis

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 31, No. 2, July – December 2016, pp. 723 – 744 Pakistan-Afghanistan Relations from 1978 to 2001: An Analysis Khalid Manzoor Butt GC University, Lahore, Pakistan. Azhar Javed Siddqi Government Dayal Singh College, Lahore, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The entry of Soviet forces into Afghanistan in December 1979 was a watershed happening. The event brought about, inter alia, a qualitative change in Pakistan‟s relations with Afghanistan as well as balance of power in South Asia. The United States and its allies deciphered the Soviet move an attempt to expand its influence to areas vital for Washington‟s interests. America knitted an alliance of its friends to put freeze on Moscow‟s advance. Pakistan, as a frontline state, played a vital role in the eviction of the Soviet forces. This paved the way for broadening of traditional paradigm of Islamabad‟s Afghan policy. But after the Soviet military exit, Pakistan was unable to capitalize the situation to its advantage and consequently had to suffer from negative political and strategic implications. The implications are attributed to structural deficits in Pakistan‟s Afghan policy during the decade long stay of Red Army on Afghanistan‟s soil. Key Words: Durand Line, Pashtunistan, Saur Revolution, frontline state, structural deficits, expansionism, Jihad, strategic interests, Mujahideen, Pariah, Peshawar Accord Introduction Pakistan-Afghanistan relations date back to the partition of the subcontinent in August 1947. Their ties have been complex despite shared cultural, ethnic, religious and economic attributes. With the exception of the Taliban rule (1996- 2001) in Afghanistan, successive governments in Kabul have displayed varying degrees of dissatisfaction towards Islamabad.