Congolese Immigration and Xenophobia in Johannesburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity, Nationalism, and Resistance in African Popular Music

Instructor: Jeffrey Callen, Ph.D., Adjunct Faculty, Department of Performing Arts, University of San Francisco SYLLABUS ETHNOMUSICOLOGY 98T: IDENTITY, NATIONALISM AND RESISTANCE IN AFRICAN POPULAR MUSIC How are significant cultural changes reflected in popular music? How does popular music express the aspirations of musicians and fans? Can popular music help you create a different sense of who you are? Course Statement: The goal of this course is to encourage you to think critically about popular music. Our focus will be on how popular music in Africa expresses people’s hopes and aspirations, and sense of who they are. Through six case studies, we will examine the role popular music plays in the formation of national and transnational identities in Africa, and in mobilizing cultural and political resistance. We will look at a wide variety of African musical styles from Congolese rumba of the 1950s to hip-hop in a variety of African countries today. Readings: There is one required book for this course: Music is the Weapon of the Future by Frank Tenaille. Additional readings are posted on the Blackboard site for this class. Readings are to be done prior to the week in which they are discussed Listenings: Listenings (posted on Blackboard) are to be done prior to the week in which they are discussed. If entire albums are assigned for listening, listen to as much as you have time for. The Course Blog: The course blog will be an important part of this course. On it you will post your reactions to the class listenings and readings. It also lists internet resources that will prove helpful in finding supplemental information on class subjects and in preparing your final research project. -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

African Studies

FILMS, VIDEOS & DVDS FOR African Studies The Future Of Mud: A Tale of Houses and Lives in Djenne A Film by Susan Vogel Presented by the Musée National du Mali This constructed documentary blends In interviews, information with narrative to show family members the cycle of mud building and the lives of masons talk about the in Djenne, a UNESCO World Heritage city in Mali. town of Djenne, its buildings, and THE FUTURE OF MUD focuses on the mason their desires for Komusa Tenaepo, who hopes that his son will the future, as do succeed him. The film shows a day in the life of a distinguished the mason and Amadou, his young helper from Koranic master, a poor family near Timbuktu, as Komusa decides and a staff whether to allow his son to leave for schooling member of the government office charged with in the capital. preserving the architecture of Djenne. The film reveals the interdependence between The film ends with thousands of participants at the masons, buildings, and lives lived in them. It exam- annual replastering of Djenne’s beloved mosque, ines the tenuous survival of the inherited learning an age-old event, which, for the first time, has been of masons, and the hard work that sustain this specially staged in hopes of attracting tourists. style of architecture. It shows life in Djenne’s mud buildings: courtyards, a blacksmiths’ workshop, a 2007 RAI International Festival of Ethnographic Film modern white vinyl sitting room, the construction site, and Friday prayers at the great mosque. 58 minutes | color | 2007 Sale/DVD: $390 | Order #AF7-01 First Run/Icarus Films | 1 Living Memory Malick Sidibé: A Film by Susan Vogel Portrait of the Artist as a Portraitist Produced by Susan Vogel, Samuel Sidibé, Eric Engles & the Musée National du Mali A Film by Susan Vogel The film is constructed in six sketches, focusing on This short but sweet film looks at the work of the “Brilliant!.. -

África: Revista Do Centro De Estudos Africanos

África: Revista do Centro de Estudos Africanos. USP, S. Paulo, 22-23: 111-119, 1999/2000/2001. THE GLOBALIZATION OF THE URBAN MUSIC OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO Kazadi wa MUKUNA * ABSTRACT: The term “globalization” has recently become a catchword in most languages. In the field of music, globalization begets the concept of “world music”. As a new concept in music, globalization presents a challenge to scholars and layman as to the scope of its definition. In this paper I assert that regardless of its accepted definition and concept, “world music” is becoming a reality as a product of the globalization process. As a hybrid product, “world music” is feeding on music cultures of the world. As with its community, and its culture, the semantic field of its language is also at present being defined. This assertion is sustained by a myriad of sound recordings born out of experimental collabo- ration by musicians. the urban music of the Democratic Republic of Congo has contrib- uted and continues to contribute to the evolution of the hybrid product in the attainment of its new identity. Keywords: Ethnomusicology; globalization; Popular Music of DRC; World music Although it has recently become a catchword, “globalization” is an open- ended process that implies different levels of unification. It is a reality that began emerging in recent decades in economic and political arenas, specifically in refer- ence to the creation of a world market and the promotion of multinational indus- tries. However, a closer look at the semantics of the term also brings to mind that globalization is a process which has occurred since the dawn of time, consciously or otherwise, through various forms of human activities. -

Downloaded4.0 License

Journal of World Literature 6 (2021) 216–244 brill.com/jwl Congolese Literature as Part of Planetary Literature Silvia Riva | orcid: 0000-0002-0100-0569 Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy [email protected] Abstract Historically and economically, the Congo has been considered one of the most interna- tionalized states of Africa. The idea that African cultural plurality was minimized dur- ing the colonial era has to be reconsidered because textual negotiations and exchanges (cosmopolitan and vernacular, written and oral) have been frequent during and after colonization, mostly in urban areas. Through multilingual examples, this paper aims to question the co-construction of linguistic and literary pluralism in Congo and to advo- cate for the necessity of a transdisciplinary and collaborative approach, to understand the common life of African vernacular and cosmopolitan languages. I show that world literature models based on Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of negotiation between center and periphery thus have to be replaced by a concept of multilingual global history. Finally, I propose the notion of “planetary literature” as a new way of understanding the inter- connection between literatures taking care of the world. Keywords restitution – post-scriptural orality – planetary literature – multilingualism – Third Landscape 1 Recast, Return, and the Opening Up to the World Let me start by recalling an essay dating back to the early 1990s by the philoso- pher V.Y. Mudimbe. In relation to contemporary African art, he introduced the notion of reprendre (literally, “to retake”) to mean both the act of taking up an interrupted tradition, not out of a desire for purity, which would testify only to the imaginations of dead ancestors, but in a way © silvia riva, 2021 | doi:10.1163/24056480-00602006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc by-ncDownloaded4.0 license. -

Download File

Mbalax: Cosmopolitanism in Senegalese Urban Popular Music Timothy Roark Mangin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Timothy Roark Mangin All rights reserved ABSTRACT Mbalax: Cosmopolitanism in Senegalese Urban Popular Music Timothy Roark Mangin This dissertation is an ethnographic and historical examination of Senegalese modern identity and cosmopolitanism through urban dance music. My central argument is that local popular culture thrives not in spite of transnational influences and processes, but as a result of a Senegalese cosmopolitanism that has long valued the borrowing and integration of foreign ideas, cultural practices, and material culture into local lifeways. My research focuses on the articulation of cosmopolitanism through mbalax, an urban dance music distinct to Senegal and valued by musicians and fans for its ability to shape, produce, re-produce, and articulate overlapping ideas of their ethnic, racial, generational, gendered, religious, and national identities. Specifically, I concentrate on the practice of black, Muslim, and Wolof identities that Senegalese urban dance music articulates most consistently. The majority of my fieldwork was carried out in the nightclubs and neighborhoods in Dakar, the capital city. I performed with different mbalax groups and witnessed how the practices of Wolofness, blackness, and Sufism layered and intersected to articulate a modern Senegalese identity, or Senegaleseness. This ethnographic work was complimented by research in recording studios, television studios, radio stations, and research institutions throughout Senegal. The dissertation begins with an historical inquiry into the foundations of Senegalese cosmopolitanism from precolonial Senegambia and the spread of Wolof hegemony, to colonial Dakar and the rise of a distinctive urban Senegalese identity that set the proximate conditions for the postcolonial cultural policy of Négritude and mbalax. -

Revisedphdwhole THING Whizz 1

McGuinness, Sara E. (2011) Grupo Lokito: a practice-based investigation into contemporary links between Congolese and Cuban popular music. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/14703 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. GRUPO LOKITO A practice-based investigation into contemporary links between Congolese and Cuban popular music Sara E. McGuinness Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2011 School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

African History Through Popular Music” Spring 2016 Professor Lisa Lindsay

History 083: First Year Seminar “African History through Popular Music” Spring 2016 Professor Lisa LinDsay Classes: TuesDays anD ThursDays, 2:00-3:15 in Dey 306 Office hours: WeDnesDays 2:00-3:30, ThursDays, 3:30-4:30, anD by appointment Dr. LinDsay’s contact information: [email protected], Hamilton 523 Daniel Velásquez’s contact information: [email protected], Hamilton 463 Course Themes and Objectives Over the last three Decades, African popular music has founD auDiences all over the worlD. Artists like Nigeria’s Fela Kuti, South Africa’s Miriam Makeba, anD the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Papa Wemba (all pictureD above) have attracteD wiDespread attention in their home countries anD abroad not only because their music is extremely catchy, but also because they have expresseD sentiments wiDely shareD by others. Often, music such as theirs has containeD sharp political or social commentary; other times, African popular music speaks to the universal themes of love, making a living, anD having a gooD time. In all instances, however, African popular music—like popular music everywhere—has helpeD to express and Define people, their communities, anD their concerns. What music we listen to can say a lot about who we think we are, who others think we are, or who we woulD like to be. Music, then, is connecteD to identity, community, anD politics, anD these connections will form the central themes in our course. In this seminar, we will stuDy popular music as a way of unDerstanDing African history from about the 1930s to the present. In other worDs, we will listen to, read about, anD analyze music in particular times anD places in Africa so that we may learn about the societies where it was proDuceD anD consumeD. -

Congolese Rumba and Other Cosmopolitanisms La Rumba Congolaise Et Autres Cosmopolitismes

Cahiers d’études africaines 168 | 2002 Musiques du monde Congolese Rumba and Other Cosmopolitanisms La rumba congolaise et autres cosmopolitismes Bob W. White Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/161 DOI: 10.4000/etudesafricaines.161 ISSN: 1777-5353 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2002 Number of pages: 663-686 ISBN: 978-2-7132-1778-4 ISSN: 0008-0055 Electronic reference Bob W. White, « Congolese Rumba and Other Cosmopolitanisms », Cahiers d’études africaines [Online], 168 | 2002, Online since 22 November 2013, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/161 ; DOI : 10.4000/etudesafricaines.161 © Cahiers d’Études africaines Bob W. White Congolese Rumba and Other Cosmopolitanisms Most first-time listeners of Congolese popular dance music comment on the fact that this typically African musical style actually sounds like it comes from somewhere else: “Is that merengue?” or “It sounds kind of Cuban”. Given that since the beginning of Congolese modern music in the 1930s, Afro-Cuban music has been one of its primary sources of inspiration, this is obviously not a coincidence. In historical terms, it is probably more accurate to say that Cuba and other Caribbean nations have been inspired by the musical traditions of Africa, though this is not the focus of my article. While research on the question of transatlantic cultural flows can provide valuable information about the roots and resilience of culture, I am more interested in what these flows mean to people in particular times and places and ultimately what people are able to do with them, both socially and politically. -

Workshop 2019 EN

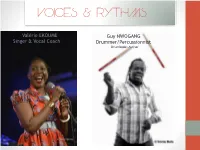

VOICES & RYTHMS Valérie EKOUME Guy NWOGANG Singer & Vocal Coach Drummer/Percussionnist DrumBooks Author Va l érie EKOUME BIO Stepping into Valérie Ekoumè's world will be one of the most interesting and fulfilling experience you may have. In her colorful world, Love is King and Afropop is the music she chooses to express it. From a musician family, Valérie EKOUME is a French Cameroonian singer based in France. Since early on, she is passionate about music and especially about singing. She grew up listening to various musical styles from congolese rumba, pop music artists (as Michael Jackson), to cameroonian Music. In 2004, she started to actively work with Manu DIBANGO in the Soul Makossa Gang and the Maraboutik Big Bang. Touring with this great musician for 8 year, was for Valerie one most incredible experience of her life, there is some things you cannot learn in school… 2005 is the year she decided to join the American School Of Modern Music, in Paris specialized in musician training. She stayed there 5 years and learnt harmony, composition, piano etc… In parallel the singer took, advanced vocal classes and completed a training in coaching vocal at the Studio Harmonic, which gave her the ability to teach vocal technics. After Djaalé in 2015, her second opus "KWIN NA KINGUE" has been released in November 2017 In this new album, and with the help of Guy Nwogang, Valérie EKOUME digged deeper into her cameroonians roots, the result is Bikutsi or even Essèwè which are popular rhythms from Cameroun. the singer belongs to this new multicultural generation and is influenced by it. -

And Their Hold on East Africa's Popular Musical

The ‘Waswahili’ and Their Hold on East Africa’s Popular Musical Culture By Stanley Gazemba Port cities are melting pots of culture world over. They spur the evolution of new cultures, languages and act as gateways to the world. It is within this context therefore that taarab, a distinct music form that defines East Africa internationally, found fertile ground along the vast coastal strip that was previously the domain of the Sultan of Zanzibar. The East African Coast has had a profound effect on the hinterland in terms of trade and cultural development and is home of the Swahili civilisation that came into strength during the Daybuli period between AD 900 and AD 1200. It is the Swahili who controlled the region’s trade from AD 1200 and bequeathed modern East Africa its lingua franca, the Swahili language and left their mark on the musical cultures of the inland indigenous peoples. A sensuous melodic music deriving from diverse cultures that impacted the coastal culture over the years, taarab easily takes centre-stage in Swahili culture. While it is not necessarily amongst the oldest music forms in the region, given that ethnic groups in the hinterland had been creating music on reed flutes and thumb pianos for generations, taarab is amongst the earliest to be recorded commercially and exported from the region. Performed and recorded for nearly a century now, taarab, which has its origins in the Arab court music of nineteenth-century Zanzibar, owes its development to the political class of Zanzibar. Sultan Said Barghash, who ruled Zanzibar between 1870 and 1888, is credited with introducing taarab to the East African coast and shepherding its growth into the cross-cultural mélange it has become today. -

Episode 48 Transcript

Hey there and welcome to episode 48 of Busy Kids Love Music, a podcast for music loving families. I’m Carly Seifert, the creator of . Busy Kids Do Piano, and I’m so happy you’re joining me today. This t episode is brought to you by the Busy Kids Love Music History p course, which is my music appreciation course especially designed i for homeschooling families. You can learn more about this interactive, comprehensive course at r busykidsdopiano.com/musichistory, and I’ll link to the course in c this episode’s show notes as well. s In our last episode, we began our podcast summer series -- n Around the World with Busy Kids Love Music -- by learning about a the folk music of Brazil. Now if you haven’t already printed your passport for this summer series, you can do so at r busykidsdopiano.com/podcast/47, and then you’ll be able to collect t stamps for your passport with each episode. Today, we’re going to continue our journey of learning about folk music from around the world by traveling to the African country of the Democratic Republic of Congo. You’ll sometimes hear this country referred to as the DRC or even simply as Congo, and it is a very large country located in central Africa. The capital of Congo is Kinshasa, and it has long been the heart of Africa’s musical scene. Prior to 1940, the city of Kinshasa was carved up and controlled by many different ethnic groups and tribes who each maintain their own folk music styles and traditions.