A Speck in the Sky Speck in the Sky Peter Moran, Td Illustrated by John Batchelor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanctuary Magazine Which Exemplary Sustainability Work Carried Westdown Camp Historic Environments, Access, Planning and Defence

THE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE SUSTAINABILITY MAGAZINE Number 43 • 2014 THE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE SUSTAINABILITY MAGAZINE OF DEFENCE SUSTAINABILITY THE MINISTRY MOD celebrates thirty years of conserving owls and raptors on Salisbury Plain Climate change adaptation Number 43 • 2014 and resilience on the MOD estate Spend 2 Save switch on the success CONTACTS Foreword by Jonathan Slater Director General Head Office and Defence Infrastructure SD Energy, Utilities & Editor Commissioning Services Organisation Sustainability Team Iain Perkins DIO manages the MOD’s property The SD EUS team is responsible for Energy Hannah Mintram It has been another successful year infrastructure and ensures strategic Management, Energy Delivery and Payment, for the Sanctuary Awards with judges management of the Defence estate as a along with Water and Waste Policy whole, optimising investment and Implementation and Data across the MOD Designed by having to choose between some very providing the best support possible to estate both in the UK and Overseas. Aspire Defence Services Ltd impressive entries. I am delighted to the military. Multi Media Centre see that the Silver Otter trophy has Energy Management Team Secretariat maintains the long-term strategy Tel: 0121 311 2017 been awarded to the Owl and Raptor for the estate and develops policy on estate Editorial Board Nest Box Project on Salisbury Plain. management issues. It is the policy lead for Energy Delivery and Payment Team Julia Powell (Chair) This project has been running for sustainable estate. Tel: 0121 311 3854 Richard Brooks more than three decades and is still Water and Waste Policy Implementation thriving thanks to the huge Operational Development and Data Team Editorial Contact dedication of its team of volunteers. -

ENFORD PARISH ANNUAL MEETING Draft Minutes of the Meeting Held at Enford Parish Hall Onwednesday 3Rd April 2013 at 7.30P.M

ENFORD PARISH ANNUAL MEETING Draft Minutes of the meeting held at Enford Parish Hall onWednesday 3rd April 2013 at 7.30p.m. Present: Mr Ken Monk Chairman, Enford Parish Council Mr Adrian Orr Vice Chairman, Enford Parish Council Mrs Tessa Manser, Mrs Jane Young, Councillors Mr Norman Beardsley Councillor Mr Michael Fay, Mr Stan Bagwell Councillors Lt Col(retd) Nigel Linge, PC Ivor Noyce, Mr Andrew Marx, Mr Richard Petitt, Mr Steve Becker, Mr Steve Brown, Mrs D’Arcy-Irvine, Mr D’Arcy-Irvine, Mrs LowenaHarbottle, Mr David Harbottle, Mr Nigel Murray, Mr Hamish Scott-Dalgleish Mrs Elizabeth Harrison Clerk, Enford Parish Council The Meeting was opened at 7.35pm by the Vice Chairman of the Parish Council, Mr Adrian Orr 1 Apologies: Apologies were received from Mr Charles Howard of Wiltshire Council who is standing for re-election on 2 nd May and therefore decline to attend as it might be considered electioneering. The Chairmn thanked him for all his contributions throughout the year. Apologies were also received from Mr Martin Webb and Mrs Tanya Becker (Newsletter Committee). 2 Welcome by the Vice Chairman of the Parish Council –Mr Adrian Orr Mr Orr welcomed various members of the village, committees and groups thanking them for their time and hard work in the last year. 3 Verify Minutes of the Meeting held On 4-Apr-12 The Draft Minutes from the Annual Parish Meeting of 2012 were considered, approved and signed by Mr Adrian Orr. 4 Matters Arising No matters arose from members of the Parish Council. Mrs Judy D’Arcy-Irvine however raised the matter of a previous meeting having been recorded and the fact that she wanted the tape. -

Exercise Lion

WINTER 2011 Station ying THE COMMUNITY MAGAZINE OF WATTISHAM FL EXERcise Lion sun ARMY helicopter and vehicle mechanics have swapped their spanners for rifles for a gruelling exercise in the dust and heat of Cyprus 656 SQuaDRon 4 Regt aac MARitime stRIKE Army Attack Aviation from the Sea ARmy piLot ALso saVes LIVes in PADRes coRneR EXERcise ALLgau DRagon the SKieS ABOVE OpeRation HERRicK AfGHAniSTAN Unit NewS | MOD POLICE | AWArdS | RAFMSA ENDURO CHAMPIONSHIP 2011 THE EAGle CONTENTS THE EAGle CONTENTS 3 2 From the Editor: Lt Col (Retd) RW SILK MBE Station Staff Officer elcome to the winter (Christmas) edition of The Eagle, which again covers operations, W training and a host of other activities back at Wattisham, our Home Base. You will see from the Station 2 Commander’s introduction that the past few months have been somewhat hectic with all kinds of activities, which has pushed the station very much into the media spotlight. Of course on the downside the Station Commander, Col Neale Moss, is preparing to leave us to be replaced by Col Andy Cash in the New Year. I will not dwell on this at the moment as the various reports of the ‘Governor’’ leaving will be carried in the next edition. Finally, the editorial team wishes all our readers a peaceful Christmas and the very best of fortune in the New Year. 30 06 I Foreword 26 I 7 Air Assault Battalion REME 36 I Welfare Matters Introduction by Colonel Neale Moss News and updates from 7 Air Assault News and updates from the various Unit OBE, AH Force Commander, Wattisham Battalion REME, including Exercises Lion Welfare Offices. -

Enford Information Board

For where to visit, eat, and stay VALE OF PEWSEY 8 HISTORIC SITES 3 1 in association with 6 pewsey heritage centre ENFORD 7 pewseyheritagecentre.org.uk 2 4 Police Murder and Suicide In 1913 Enford came under the glare of the 5 national media after a sensational murder and suicide. William Crouch, the Sergeant at Netheravon (right), was involved in a disciplinary case against Constable Pike, charged with being in a public house (The Three Horseshoes in Enford) while on duty. Found guilty on 31 March 1913, Pike was told he would be moved to another post: Pike accused Sergeant Crouch of lying. Later that evening, Constable The parish of Enford contains Enford village, and includes the villages and hamlets of Compton, Fifield, East Chisenbury, West 10 Pike left his home to go on his round, taking a shotgun with him. It The Royal School of Artillery is based nearby at Larkhill, and live Chisenbury, Littlecott, New Town, Longstreet and Coombe. Until the 16th century, these were considered separate settlements and is believed that he shot Sergeant Crouch in the head at the bottom firing is conducted on the plain to the west of Enford all year were taxed independently. of Coombe Hill then killed himself on the footbridge (10) between round. Access to Salisbury Plain Training Area is regulated Coombe and Fifield. Pike’s body was found the next day floating in by various range byelaws. Always comply with local A brief history Longstraw thatch being harvested the River Avon. signs and flags. Rights of way in Range Danger There is archaeological evidence showing human activity in this area from the Areas are closed when red flags are flying. -

Name & Address Of

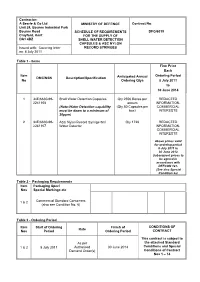

Contractor: A Searle & Co Ltd MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Contract No: Unit 24, Bourne Industrial Park Bourne Road SCHEDULE OF REQUIREMENTS DFG/6019 Crayford, Kent FOR THE SUPPLY OF DA1 4BZ SHELL WATER DETECTION CAPSULES & ASC NYLON Issued with: Covering letter RECORD SYRINGES on: 8 July 2011 Table 1 - Items Firm Price Each Item Ordering Period DMC/NSN Description/Specification Anticipated Annual No Ordering Qtys 8 July 2011 to 30 June 2014 1 34E/6630-99- Shell Water Detection Capsules Qty 2556 Boxes per REDACTED 2241108 annum INFORMATION- (Note-Water Detection capability (Qty 80 Capsules per COMMERCIAL must be down to a minimum of box) INTERESTS 30ppm) 2 34E/6630-99- ASC Nylon Record Syringe 5ml Qty 1728 REDACTED 2241107 Water Detector INFORMATION- COMMERCIAL INTERESTS Above prices valid for ordering period 8 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. Subsequent prices to be agreed in accordance with DEFCON 127. (See also Special Condition 2a) Table 2 - Packaging Requirements Item Packaging Spec/ Nos Special Markings etc Commercial Standard Containers 1 & 2 (also see Condition No. 6) Table 3 - Ordering Period Item Start of Ordering Finish of CONDITIONS OF Rate Nos Period Ordering Period CONTRACT This contract is subject to As per the attached Standard 1 & 2 8 July 2011 Authorised 30 June 2014 Conditions and Special Demand Order(s) Conditions of Contract Nos 1 – 14 DFG/6019 STANDARD CONDITIONS OF CONTRACT The following Defence Conditions (DEFCONs) shall apply: DEFCON 5 (Edn 07/99) - MOD Forms 640 – Advice and Inspection Note DEFCON 5J (Edn 07/08) - Unique Identifiers DEFCON 68 (Edn 05/10) - Supply of Hazardous Articles and Substances DEFCON 76 (Edn 12/06) - Contractor’s Personnel at Government Establishments DEFCON 127 (Edn 10/04) - Price Fixing Condition for Contracts of Lesser Value DEFCON 129 (Edn 07/08) - Packaging (For Articles other than Ammunition and Explosives) – see also Condition No 6 Note: For the purposes of this Contract Clause 12 - Spares Price Labelling is not applicable. -

Tidworth's Transformation

DThe magazineIO of the Defence Infrastructure Organisation logue Issue 5 September 2012 Meet DIO’s Chief Operating Officer Mark Hutchinson Soldiers unearth Salisbury Plain secrets Tidworth’s transformation See how a £455million project is making life better for 5,200 soldiers Win a jar of DIO honey Welcome Contents from Andrew Manley > In brief 2 > Step-change 3 Welcome to the fifth edition of DIOlogue. > The next 17 pages carry features and news stories that highlight how Future Business Network 5 our work supports the Armed Forces and also shine a spotlight on our > Building a performance culture 6 transformation. > From rehab to Royal Marine 8 Looking to our transformation programme, we’ve devoted pages three to six to the innovative ways in which our organisation is changing. > Inside Nuclear Equipment From tapping into the diverse talent and skills we already have, to and Support 10 the making of leadership pledges, to the birth of the inventive Future Business Network, we are honouring our vow to create a remarkable > Soldiers unearth Salisbury organisation. Plain secrets 11 On page 13 you’ll find two pictures that exemplify what DIO is about – delivering infrastructure that > Tidworth’s transformation 13 makes a real difference. One image is of Tidworth in 2008 close to the beginning of a £455m scheme to improve accommodation for 5,200 soldiers based there. The other was taken as the project draws to a > Practice makes perfect 14 close. I am sure you will agree the difference is extraordinary. > A taste of honey 16 On page 9 Ellie Hughes writes about a new £3.2m Royal Marine Rehabilitation Facility which we, along with our industry partners, constructed for the Royal Navy. -

Mark Preston Director of Business Resilience

Mark Preston Director of Business Resilience Ministry of Defence Main Building (01/I/52) Whitehall London SW1A 2HB United Kingdom Telephone [MOD]: +44 (0)20 7218 0462 Facsimile [MOD]: +44 (0)20 7218 9078 E-mail: [email protected] DBR-DefSy-04-03-11 15 May 2013 Guarding and Civil Policing Change Programme – Update I am writing to announce a decision about future guarding arrangements at Front Line Command (FLC) sites that are set at Guarding Levels 1 and 2. The main points are: i. Following formal consultation with the Trades Unions and Defence Police Federation, it has been decided that MGS and MDP complements will be withdrawn from these sites, with guarding responsibilities transferring to the MPGS, or in some cases Regular Service personnel. A list of the sites affected is attached. The new arrangements will continue to provide effective security at all these sites. ii. I cannot yet say when the transfer will happen at each and every site. These announcements will be made locally at individual establishments once a detailed plan has been agreed for that site. Now that the overall decision has been taken, my staff are working closely with colleagues in the MGS, MDP, MPGS and TLBs to finalise and communicate those plans as quickly as possible. iii. Formal consultation is continuing on other aspects of guarding and policing change. Once this process is complete (which again I am trying to achieve as quickly as possible – hopefully within the next month) it will confirm the opportunities available elsewhere in MoD for MGS and MDP colleagues affected by the FLC decision. -

Downloaded from Skydivethemag.Com

SKYDIVTHE MAGE June 2011 skydivethemag.com The British Parachute Association Magazine The Freefall University is an independent skydiving school based in Ocaña 20 minutes south of Madrid. We are located minutes away from the modern city of Aranjuez which has all the nightlife you can handle. We have our own equipment, qualified rigger, British Instructors, facilities and professional ethic. We cater for holiday makers who wish to do an AFF course and also have BPA coaches full time for FS1 and FF1, FF2 and CH1. Remember we have a vibrant mid week dropzone so getting the jump numbers you want on holidays is not a problem. One Instructor, One Student. We provide you with your own exclusive UK AFF Instructor to personally see you through your course from ground school to completing your level 8. This means no waiting for ‘your turn’, leaving you free to focus on skydiving. Good Links with UK dropzones. We are an established school and graduates who have completed our course have been well received on UK dropzones. We offer an unparalleled level of after course support which is why many of our students choose to return for a second holiday in the sun. Package Deal. What you want, when you want. Talk to David or Lola in customer service about what type of package you would like. Whilst many things are included free such as video of all your skydives there are many options. For example you might want a car to visit Madrid or prefer to have your own hotel room. We can mix and match based on your requirements, and you can have your holiday at a time that suits you! Jump all day and don’t get bored in the evening! The FFU Ocaña is the home of the Madrid Silver Package Budget £1200a Skydivers. -

4 Regiment Army Air Corps

SUMMER 2018 YING Station THE COMMUNITY MAGAZINE OF WATTISHAM FL Exercise HIGHLAND FLING The 2018 Commando Speed March 3 Regiment Army Air Corps provided ceremonial support at the Royal Wedding Wattisham units on show at the Suffolk Show AAC & REME UNITS | MET OFFICE | THE SUFFOLK SHOW | BlaDES NETBall cluB | DRONE AWARENESS THE EAGLE CONTENTS 06 I Foreword 28 I Lets be Drone Aware in AHF 35 I Military Wives Choir Introductions by Colonel CA Bisset MBE A guide to the safe use of Drones Information about the Military Wives Choir Commander Attack Helicopter Force by the AHF Air Safety Cell. and launch of their new album which is and the new Force Sergeant Major. called Remember 1918 -2018. 30 I Blades Netball Team 10 I 3 Regiment AAC With the 2017/18 season coming to 35 I Services Welfare (WRVS) an end, Blades Netball Team reflect on News and updates from 3 The centre continues to be well used the past season and look foward to their Regiment Army Air Corps. and a warm welcome is assured to big fundraising event this summer. any newly arrived personnel. 12 I 4 Regiment AAC Childcare Centre 32 I Forces Radio BFBS News and updates from 35 I Advice on Government Early 4 Regiment Army Air Corps. Update from the Forces Radio BFBS in Years Funding for 3 to 4 year old Colchester. children, 15 or 30 hours. 18 I 7 Avn Sp Bn REME 36 I Station Welfare Departments News and updates from 7 Aviation 33 I HIVE If you need help, advice or just a chat you Support Battalion REME. -

Bustard Report Latest

From Salisbury Plain to Singapore OPERATION NIGHTINGALE - Barrow Clump, Salisbury Plain AD 900 1897 1941 1977 2015 MILITARY ARTEFACTS - FINDS REPORT Mark Khan - SPTA Conservation Group Introduction Operation Nightingale is a programme that uses archaeology to help with the rehabilitation of injured service personnel. An Operation Nightingale took place at ancient burial mound, known as Barrow Clump on Salisbury Plain. One of 306 scheduled monuments on MOD land within Salisbury Plain, Barrow Clump was on the English Heritage 'Heritage at Risk' list due to extensive burrowing by badgers. The badgers were burrowing into the site and unearthing human remains and burial relics. The project was carried out by THE RIFLES - CARE FOR CASUALTIES Charity with the support of, The Defence Infra-structure Organisation (DIO), Wessex Archaeology, English Heritage and volunteers, to excavate the site and document the remains and preserve them, before rebuilding the cemetery mound. The project was recognised as a ground-breaking archaeology project of special merit by The British Archaeological Awards 2012. This report details a cross section of finds discovered during the project, that relate to the military usage of Barrow Clump. The finds mirror the use of Salisbury Plain as a military training area from the beginning of its use to the current day. They relate not only To the tactical military use the site, but also link to the stories of individuals who trained on Salisbury Plain, with some very surprising results. OP NIGHTINGALE Artefact - 1896 Dated 7mm Mauser Cartridge Case Britain's connection with the 7mm cartridge began with the Boer War. Large quantities of rifles and ammunition came into British possession at the cessation of hostilities. -

PDF (Volume 2)

Durham E-Theses Landscape, settlement and society: Wiltshire in the rst millennium AD Draper, Simon Andrew How to cite: Draper, Simon Andrew (2004) Landscape, settlement and society: Wiltshire in the rst millennium AD, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3064/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Landscape, Settlement and Society: Wiltshire in the First Millennium AD VOLUME 2 (OF 2) By Simon Andrew Draper A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted in 2004 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Durham, following research conducted in the DepartA Archaeology ~ 2 1 JUN 2005 Table of Contents VOLUME2 Appendix 1 page 222 Appendix 2 242 Tables and Figures 310 222 AlPPlENIDRX 11 A GAZEITEER OF ROMANo-BRliTISH §EITLlEMENT SiTES TN WTLTSHm.lE This gazetteer is based primarily on information contained in the paper version of the Wiltshire Sites and Monuments Record, which can be found in Wiltshire County Council's Archaeology Office in Trowbridge. -

MARCH 2013 ISSUE No

MILITARY AVIATION REVIEW MARCH 2013 ISSUE No. 304 EDITORIAL TEAM COORDINATING EDITOR - BRIAN PICKERING WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL”[email protected]” BRITISH REVIEW - MICK BOULANGER 27 Tudor Road, Heath Town, Wolverhampton, West Midlands WV10 0LT TEL NO. 0770 1070537 EMail "[email protected]" FOREIGN FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (see Co-ordinating Editor above for address details) US FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (COORDINATING) (see above for address details) STATESIDE: MORAY PICKERING 18 MILLPIT FURLONG, LITTLEPORT, ELY, CAMBRIDGESHIRE, CB6 1HT E Mail “[email protected]” EUROPE: BRIAN PICKERING OUTSIDE USA: BRIAN PICKERING See address details above OUT OF SERVICE - ANDY MARDEN 6 CAISTOR DRIVE, BRACEBRIDGE HEATH, LINCOLN LN4 2TA E-MAIL "[email protected]" MEMBERSHIP/DISTRIBUTION - BRIAN PICKERING MAP, WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL.”[email protected]” ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION (Jan-Dec 2013) UK £40 EUROPE £55 ELSEWHERE £60 @MAR £20 (EMail/Internet Only) MAR PDF £20 (EMail/Internet Only) Cheques payable to “MAP” - ALL CARDS ACCEPTED - Subscribe via “www.mar.co.uk” ABBREVIATIONS USED * OVERSHOOT f/n FIRST NOTED l/n LAST NOTED n/n NOT NOTED u/m UNMARKED w/o WRITTEN OFF wfu WITHDRAWN FROM USE n/s NIGHTSTOPPED INFORMATION MAY BE REPRODUCED FROM “MAR” WITH DUE CREDIT EDITORIAL With this issue comes bad news from the USA resulting from the continuing budget stand off that is bringing in major mandatory reductions in the current year’s budget. The armed forces, along with all other government departments, are taking drastic steps to reduce their spending and one way they have adopted is to cancel air shows at bases and aircraft participation at other events (there is even talk about the future of the Tnunderbirds and Blue Angels!).