©2015 Benjamin A. Dworkin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

Job Killers” in the News: Allegations Without Verification

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, JUNE 2012 “Job Killers” in the News: Allegations without Verification STUDY AUTHORS1 Peter Dreier, Ph.D. Christopher R. Martin, Ph.D. Dr. E.P. Clapp Distinguished Professor of Politics Professor and Interim Head Chair, Urban & Environmental Policy Department Department of Communication Studies Occidental College University of Northern Iowa Phone: (323) 259-2913 FAX: (323) 259-2734 Phone: (319) 273-6118 FAX: (319) 273-7356 Website: http://employees.oxy.edu/dreier Website: http://www.uni.edu/martinc EXECUTIVE SUMMARY “Job Killers” in the News: Allegations without Verification “…there’s a simple rule: You say it again, and you say it again, and you say it again…and about the time that you’re absolutely sick of saying it is about the time that your target audience has heard it for the first time.”2 -- Frank Luntz, Republican pollster A comprehensive study analyzes the frequency of the “job killer” term in four mainstream news media since 1984, how the phrase was used, by whom, and—most importantly— whether the allegations of something being a “job killer” were verified by reporters in their stories. The study’s key findings include the following: • Media stories with the phrase “job killer” spiked dramatically after Barack Obama was elected president, particularly after he took office. The number of stories with the phrase “job killer” increased by 1,156% between the first three years of the George W. Bush administration (16 “job killer” stories) and the first three years of the Obama administration (201 “job killer” stories). • The majority of the sources of stories using the phrase “job killer” were business spokepersons and Republican Party officials. -

Heritage’S Plan For

What leaders say about Heritage’s plan for: AMERIC A N DRE A M “Getting our country’s fiscal house in order is no easy task. Thankfully, our friends at The Heritage Foundation have done the hard work of thinking through and creating public policies that get government under control and save the American dream for this generation and the next.” — Senator Jim DeMint (R-S.C.) “The analysis of our fiscal problems is compelling, and the proposed solution is bold and imaginative.” — Ambassador John Bolton “The Heritage Foundation’s plan to save the American dream would create economic certainty for businesses by putting our nation on a more stable economic course and giving businesses the freedom to expand.” — Andrew F. Puzder, CEO of CKE Restaurants Inc. (Hardee’s and Carl’s Jr.) “… a plan that truly reforms… This plan is the cure for our ‘disease.’” AMERIC A N DRE A M — Cal Thomas, Syndicated Columnist “Comprehensive tax reform is an essential element of restoring fiscal sanity and spurring economic growth in the country. The Heritage Foundation’s proposal moves the country’s tax code in the right direction toward a more low-rate, flat tax.” — Arthur B. Laffer, Ph.D., the Father of Supply-Side Economics “America does not have to be a country in decline. Do we have choices to make? Yes. And I encourage anyone who is serious about making the right choices to read The Heritage Foundation’s plan to fix the debt, cut spending, and restore prosperity.” — Steve Forbes, Editor-in-Chief, Forbes magazine 214 Massachusetts Avenue N.E. -

Chairman's Report

2014-2015 Chairman’s Report A Bi-annual report summarizing the organization’s activities in 2014 and 2015. “At the root of everything that we’re trying to accomplish is the belief that America has a mission. We are a nation of freedom, living under God, believing all citizens must have the opportunity to grow, create wealth, and build a better life for those who follow. If we live up to these moral values, we can keep the American dream alive for our children and our grandchildren, and America will remain mankind’s best hope” — Ronald Reagan 1 2 A Message From the Chairman... Dear Fellow Republicans, It is a great time to be a Republican in Cuyahoga County! 2014 was an exciting and busy year as we worked to re- elect our incumbent statewide candidates and further develop our voter engagement efforts with the creation of the Advocacy Council. While the work is constant, it builds a foundation for continued Republican success, such as the 70% of Republican endorsed candidates that were elected to local office in 2015. In 2014, Ohio Governor John Kasich won Cuyahoga County in his gubernatorial re-election; this was the first time Cuyahoga County voted Republican since Senator George Voinovich’s 2004 re-election to the U.S. Senate. Cuyahoga County was a regular campaign stop for many of our incumbent Republican officeholders, including a rally for Governor Kasich with U.S. Senator Rob Portman and New Jersey Governor Chris Christie. In the end, winning Cuyahoga County was the icing on the cake for Governor Kasich who won a historic 86 out of 88 Ohio counties. -

The Rules of #Metoo

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2019 Article 3 2019 The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Jessica A. (2019) "The Rules of #MeToo," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2019 , Article 3. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2019/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke† ABSTRACT Two revelations are central to the meaning of the #MeToo movement. First, sexual harassment and assault are ubiquitous. And second, traditional legal procedures have failed to redress these problems. In the absence of effective formal legal pro- cedures, a set of ad hoc processes have emerged for managing claims of sexual har- assment and assault against persons in high-level positions in business, media, and government. This Article sketches out the features of this informal process, in which journalists expose misconduct and employers, voters, audiences, consumers, or professional organizations are called upon to remove the accused from a position of power. Although this process exists largely in the shadow of the law, it has at- tracted criticisms in a legal register. President Trump tapped into a vein of popular backlash against the #MeToo movement in arguing that it is “a very scary time for young men in America” because “somebody could accuse you of something and you’re automatically guilty.” Yet this is not an apt characterization of #MeToo’s paradigm cases. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Chairmen Insist on Public Plan Blue Dogs Remain Opposed

VOL. 54, NO. 143 WEDNESDAY, JUNE 10, 2009 $3.75 Chairmen Insist On Public Plan Blue Dogs Remain Opposed By Steven T. Dennis and Tory Newmyer ROLL CALL STAFF House Democratic chairmen plan to disregard conservative Blue Dogs who are opposing a government-sponsored health in- surance plan as part of a sweeping reform bill, in what is shaping up to be the biggest internal battle of President Barack Obama’s young agenda. Just days after Blue Dogs insist- ed that no public option be includ- Bill Clark/Roll Call ed in the package — except as a Sen. Chris Dodd, seen at a news conference Tuesday on the impact of high health costs, is right in possible fallback that could be the middle of issues at the top of the Congressional agenda — and he faces a tough re-election fight. “triggered” years from now — the File Photo powerful chairmen unveiled a draft Rep. Charlie Rangel: “We’re bill that strongly backs a public op- going to have a public plan.” Dodd Juggles Triple Challenge tion without such a trigger. “There won’t be any considera- of writing the bill — Rangel, En- By David M. Drucker Housing and Urban Affairs chair- tion of the trigger,” Ways and ergy and Commerce Chairman and Emily Pierce K Street has mixed views of man, but he also is acting as a stand- Means Chairman Charlie Rangel Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) and ROLL CALL STAFF health proposal, p. 9. in for an ailing Health, Education, (D-N.Y.) said. “We’re going to Education and Labor Chairman President Barack Obama’s am- Labor and Pensions Chairman Ed- have a public plan and we’re not George Miller (D-Calif.) — re- bitious goals of rewriting the books thin Sen. -

Inspiring Americans to Greatness Attendees of the 2019 Freedom Conference Raise Their Hands in Solidarity with Hong Kong Pro-Democracy Protesters

Annual Report 2019-20 Inspiring Americans to Greatness Attendees of the 2019 Freedom Conference raise their hands in solidarity with Hong Kong pro-democracy protesters The principles espoused by The Steamboat Institute are: Limited taxation and fiscal responsibility • Limited government • Free market capitalism Individual rights and responsibilities • Strong national defense Contents INTRODUCTION EMERGING LEADERS COUNCIL About the Steamboat Institute 2 Meet Our Emerging Leaders 18 Letter from the Chairman 3 MEDIA COVERAGE AND OUTREACH AND EVENTS PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT Campus Liberty Tour 4 Media Coverage 20 Freedom Conferences and Film Festival 8 Social Media Analytics 21 Additional Outreach 10 FINANCIALS TONY BLANKLEY FELLOWSHIP 2019-20 Revenue & Expenses 22 FOR PUBLIC POLICY & AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM FUNDING About the Tony Blankley Fellowship 11 2019 and 2020 Fellows 12 Funding Sources 23 Past Fellows 14 MEET OUR PEOPLE COURAGE IN EDUCATION AWARD Board of Directors 24 Recipients 16 National Advisory Board 24 Our Team 24 The Steamboat Institute 2019-20 Annual Report – 1 – About The Steamboat Institute Here at the Steamboat Institute, we are Defenders of Freedom When we started The Steamboat Institute in 2008, it was and Advocates of Liberty. We are admirers of the bravery out of genuine concern for the future of our country. We take and rugged individualism that has made this country great. seriously the concept that freedom is never more than one We are admirers of the greatness and wisdom that resides generation away from extinction. in every individual. We understand that this is a great nation because of its people, not because of its government. The Steamboat Institute has succeeded beyond anything Like Thomas Jefferson, we would rather be, “exposed to we could have imagined when we started in 2008. -

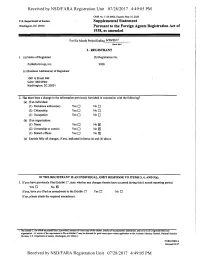

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/28/2017 4:49:05 PM

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/28/2017 4:49:05 PM OMB No. 1124-0002; Expires May 31,2020 U.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 6/30/2017 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Podesta Group, Inc. 5926 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 1001 G Street NW Suite 1000 West Washington, DC 20001 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes • No • (2) Citizenship Yes • No • (3) Occupation Yes • No • (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes • No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No H (3) Branch offices Yes • No H (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes • No 0 If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No • If no, please attach the required amendment. 1 The Exhibit C, tor which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy of the charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organizatioa (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

Ronald Reagan in Memoriam

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Features Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies 6-6-2004 Ronald Reagan in Memoriam Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/features Recommended Citation "Ronald Reagan in Memoriam" (2004). Features. Paper 91. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/features/91 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Features by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ronald Reagan In Memoriam - Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies - Grand Valley... Page 1 of 32 Ronald Reagan In Memoriam Ronald Reagan In Memoriam Our 40th president's life, career, death, and funeral are recalled in this Hauenstein Center focus. Detroit Free Press A Milliken Republican was driven to honor Reagan Column By Dawson Bell - Detroit Free Press (June 14, 2004) "The Michigan Republican Party Jerry Roe served as executive director in the 1970s wasn't exactly ground zero in the Reagan Revolution." FULL TEXT One thing's for sure, he kept to the script Column By Rochelle Riley - Detroit Free Press (June 11, 2004) "He took on his greatest acting role, as president of the United States, in a sweeping epic drama about one national superpower making itself stronger while growing tired of a second nipping at its heels with waning threats of nuclear annihilation." FULL TEXT Media do not tell the truth about Reagan Column By Leonard Pitts Jr. - Detroit Free Press (June 11, 2004) "Philadelphia, a speck of a town north and east of Jackson, is infamous as the place three young civil rights workers were murdered in 1964 for registering black people to vote. -

Jesse Ferguson RE: Benenson's Cocktails on 4.10.15

EVENT MEMO FR: Jesse Ferguson RE: Benenson’s Cocktails on 4.10.15 This is an off-the-record cocktails with the key national reporters, especially (though not exclusively) those that are based in New York. Much of the group includes influential reporters, anchors and editors. The goals of the dinner include: (1) Give reporters their first thoughts from team HRC in advance of the announcement (2) Setting expectations for the announcement and launch period (3) Framing the HRC message and framing the race (4) Enjoy a Frida night drink before working more TIME/DATE: As a reminder, this is called for 6:30 p.m. on Friday, April 10th. There are several attendees – including Diane Sawyer – who will be there promptly at 6:30 p.m. but have to leave by 7 p.m. LOCATION: The address of his home is 60 E. 96th Street, #12B, New York, 10128. CONTACT: If you have last minute emergencies please contact me (703-966-2689) or Joel Benenson (917-991-0155). FOOD: This will include cocktails and passed hours devours. REPORTER RSVPs YES 1. ABC - Cecilia Vega 2. ABC - David Muir 3. ABC – Diane Sawyer 4. ABC – George Stephanoplous 5. ABC - Jon Karl 6. Bloomberg – John Heillman 7. Bloomberg – Mark Halperin 8. CBS - Norah O'Donnell 9. CBS - Vicki Gordon 10. CNN - Brianna Keilar 11. CNN - David Chalian 12. CNN – Gloria Borger 13. CNN - Jeff Zeleny 14. CNN – John Berman 15. CNN – Kate Bouldan 16. CNN - Mark Preston 17. CNN - Sam Feist 18. Daily Beast - Jackie Kucinich 19. GPG - Mike Feldman 20. -

ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWS Since Inception of the Program in 1994

Update on the 141 ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWS Since Inception of the Program in 1994 24th Annual Robert Novak Journalism Fellowship Awards Dinner May 10, 2017 2017 ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWSHIP AWARD WINNERS HELEN R. ANDREWS | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “Eminent Boomers: The Worst Generation from Birth to Decadence” Helen earned a degree in religious studies from Yale University, where she served as speaker of the Yale Political Union. Currently a freelance writer and commentator, she served for three years as a policy analyst for the Centre for Independent Studies, a leading conservative think tank in suburban Sydney, Australia. Previously, she was an associate editor at National Review. Her work has appeared in First Things, Claremont Review of Books, The American Spectator, The Weekly Standard and others. MADISON E. ISZLER | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “What’s Killing Middle-Aged White Women—and What it Means for Society” Madison holds a master’s degree, cum laude, in political philosophy and economics from The King’s College. Currently, she is an Intercollegiate Studies Institute Reporting Fellow. She has interned for USA Today and the National Association of Scholars and was a reporter for the New York Post. Her work has appeared in numerous outlets, including the Raleigh News & Observer, Charlotte Observer, New York Post and Miami Herald. Originally from Florida, she resides in Raleigh, North Carolina. RYAN LOVELACE | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “Hiding in Plain Sight: Criminal Illegal Immigration in America” An Illinois native, Ryan attended and played football for the University of Wyoming. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in journalism from Butler University.