Deconstructing the Outsider Puzzle: the Legitimation Journey of Novelty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edmond Halley and His Recurring Comet

EDMOND HALLEY AND HIS RECURRING COMET “They [the astronomers of the flying island of Laputa] have observed ninety-three different comets and settled their periods with great exactness. If this be true (and they affirm it with great confidence), it is much to be wished that their observations were made public, whereby the theory of comets, which at present is very lame and defective, might be brought into perfection with other parts of astronomy.” — Jonathan Swift, GULLIVER’S TRAVELS, 1726 HDT WHAT? INDEX HALLEY’S COMET EDMOND HALLEY 1656 November 8, Saturday (Old Style): Edmond Halley was born. NEVER READ AHEAD! TO APPRECIATE NOVEMBER 8TH, 1656 AT ALL ONE MUST APPRECIATE IT AS A TODAY (THE FOLLOWING DAY, TOMORROW, IS BUT A PORTION OF THE UNREALIZED FUTURE AND IFFY AT BEST). Edmond Halley “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX HALLEY’S COMET EDMOND HALLEY 1671 February 2, Friday (1671, Old Style): Harvard College was given a “3 foote and a halfe with a concave ey-glasse” reflecting telescope. This would be the instrument with which the Reverends Increase and Cotton Mather would observe a bright comet of the year 1682. ASTRONOMY HALLEY’S COMET HARVARD OBSERVATORY ESSENCE IS BLUR. SPECIFICITY, THE OPPOSITE OF ESSENCE, IS OF THE NATURE OF TRUTH. Edmond Halley “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX HALLEY’S COMET EDMOND HALLEY 1676 Edmond Halley was for six weeks the guest of the British East India Company at their St. Helena colony in the South Atlantic for purposes of observation of the exceedingly rare transit of the planet Venus across the face of the sun. -

PUMP STATION MECHANIC I/II DEFINITION to Perform Semi-Skilled and Skilled Work in the Installation Maintenance and Repair Of

PUMP STATION MECHANIC I/II DEFINITION To perform semi-skilled and skilled work in the installation maintenance and repair of pumps, motors, chain drives, valves and related equipment; and to do related work as required. DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS Pump Mechanic I: This is the entry level class in the Pump Mechanic series. Positions in this class normally perform beginning level mechanical repair and maintenance work on a wide variety of wastewater and storm water lift station and equipment. Under this class, individuals employed at the entry level (Pump Mechanic I) may, based on the acquisition of higher skill levels through training and experience, become eligible for promotion to the Pump Mechanic II position. This promotion would be based on satisfactory demonstration of skills through examination or certification from an accepted organization, training institution, or school and demonstrated ability to perform high level maintenance and repairs on City pump stations. Particular skill areas of interest are installation and maintenance of telemetry systems, computerized pump control systems and pump preventative maintenance programs. Pump Mechanic II: This is the journey level class in the Pump Mechanic series. Positions assigned to this class are flexibly staffed and are expected to perform the most skilled repair and maintenance work and have a thorough knowledge of the operational characteristics, maintenance and repair methods and techniques and most typical system difficulties for the full range of equipment and operational systems in a lift station. All positions assigned to this class require the ability to work independently, exercising judgment and initiative. Pump Station Mechanics II may also be expected to assist in the oversite of less experienced personnel. -

FROM LONGITUDE to ALTITUDE: INDUCEMENT PRIZE CONTESTS AS INSTRUMENTS of PUBLIC POLICY in SCIENCE and TECHNOLOGY Clayton Stallbau

FROM LONGITUDE TO ALTITUDE: INDUCEMENT PRIZE CONTESTS AS INSTRUMENTS OF PUBLIC POLICY IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Clayton Stallbaumer* I. INTRODUCTION On a foggy October night in 1707, a fleet of Royal Navy warships ran aground on the Isles of Scilly, some twenty miles southwest of England.1 Believing themselves to be safely west of any navigational hazards, two thousand sailors discovered too late that they had fatally misjudged their position.2 Although the search for an accurate method to determine longitude had bedeviled Europe for several centuries, the “sudden loss of so many lives, so many ships, and so much honor all at once” elevated the discovery of a solution to a top national priority in England.3 In 1714, Parliament issued the Longitude Act,4 promising as much as £20,0005 for a “Practicable and Useful” method of determining longitude at sea; fifty-nine years later, clockmaker John Harrison claimed the prize.6 Nearly three centuries after the fleet’s tragic demise, another accident, also fatal but far removed from longitude’s terrestrial reach, struck a nation deeply. Just four days after its crew observed a moment’s silence in memory of the Challenger astronauts, the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon reentry, killing all on board.7 Although * J.D., University of Illinois College of Law, 2006; M.B.A., University of Illinois College of Business, 2006; B.A., Economics, B.A., History, Lake Forest College, 2001. 1. DAVA SOBEL, LONGITUDE: THE TRUE STORY OF A LONE GENIUS WHO SOLVED THE GREATEST SCIENTIFIC PROBLEM OF HIS TIME 12 (1995). -

High Pressure Pumps

HIGH PRESSURE PUMPS 120 INDUSTRIAL DR. SLIDELL, LOUISIANA 70460 USA P: 985.649.3000 | F: 985.649.4300 THOMASPUMP.COM HIGH PRESSURE PUMPS T-GTO / T-GTO XD / T-GEAR T-GTO / T-GTO XD / T-GEAR are high pressure pumps designed for critical applications, making them the most reliable high-pressure pumps in the marketplace. FIELDS OF APPLICATION T-GTO / T-GTO XD / T-GEAR • Sanitation Cleaning • Paper Mill Showering • Truck Cleaning Facilities • Brine Injection • Environmental Waste Disposal • Boiler Feed • Mill De-scaling • Oil and Gas DESIGN T-GTO series is a heavy duty oil lubricated Pitot tube T-GTO XD series has been developed for low flow, high pump designed for critical applications making it the most pressure applications. The Pitot tube design produces a reliable high-pressure pump in the marketplace. stable, pulsation free flow. The ability to operate with low minimum flow makes the pump suitable for a wide variety With a full range of capacities from 30-400 GPM (6-100 of applications, within its performance envelope. m3hr) and pressures reaching 1600-psi (110 bar) the T-GTO offers a variety of pump choices. A robust power frame, features that include only two basic working parts: T-GEAR series is a single-stage, parallel shaft speed 1) a rotating case and 2) a stationary pick-up tube, and a increaser. Heat dissipation is from a dynamically balanced mechanical seal that only seals against suction pressure, fan blowing across the finned gearbox casing. The design ensure pump reliability in the most demanding applications. is for horizontal installation only. -

Cyclic Hydraulic Actuation for Soft Robotic Devices

2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) Daejeon Convention Center October 9-14, 2016, Daejeon, Korea Cyclic Hydraulic Actuation for Soft Robotic Devices Robert K Katzschmann, Austin de Maille, David L Dorhout, Daniela Rus Abstract— Undulating structures are one of the most diverse Soft Body and successful forms of locomotion in nature, both on ground Pressurized Liquid and in water. This paper presents a comparative study for actuation by undulation in water. We focus on actuating a 1DOF systems with several mechanisms. A hydraulic pump attached to a soft body allows for water movement between two inner Deflection cavities, ultimately leading to a flexing actuation in a side-to- side manner. The effectiveness of six different, self-contained designs based on centrifugal pump, flexible impeller pump, Cyclic Actuator external gear pump and rotating valves are compared. These hydraulic actuation systems combined with soft test bodies were De-Pressurized Liquid then measured at a lower and higher oscillation frequency. The deflection characteristics of the soft body, the acoustic noise of the pump and the overall efficiency of the system Fig. 1: Cyclic hydraulic actuation of a soft body through an are recorded. A brushless, centrifugal pump combined with a actuator producing undulating motions. novel rotating valve performed at both test frequencies as the most efficient pump, producing sufficiently large cyclic body deflections along with the least acoustic noise among all pumps tested. An external gear pump design produced the largest body and compact actuation with long endurance for soft fluidic deflection, but consumes an order of magnitude more power actuators [1]. -

Who Invented the Calculus? - and Other 17Th Century Topics Transcript

Who invented the calculus? - and other 17th century topics Transcript Date: Wednesday, 16 November 2005 - 12:00AM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall WHO INVENTED THE CALCULUS? Professor Robin Wilson Introduction We’ve now covered two-thirds of our journey ‘From Caliphs to Cambridge’, and in this lecture I want to try to survey the mathematical achievements of the seventeenth century – a monumental task. I’ve divided my talk into four parts – first, the movement towards the practical sciences, as exemplified by the founding of Gresham College and the Royal Society. Next, we’ll gravitate towards astronomy, from Copernicus to Newton. Thirdly, we visit France and the gradual movement from geometry to algebra (with a brief excursion into some new approaches to pi) – and finally, the development of the calculus. So first, let’s make an excursion to Gresham College. Practical science The Gresham professorships arose from the will of Sir Thomas Gresham, which provided for £50 per year for each of seven professors to read lectures in Divinity, Astronomy, Music, Geometry, Law, Physic and Rhetoric. As the Ballad of Gresham College later described it: If to be rich and to be learn’d Be every Nation’s cheifest glory, How much are English men concern’d, Gresham to celebrate thy story Who built th’Exchange t’enrich the Citty And a Colledge founded for the witty. From its beginning, Gresham College encouraged the practical sciences, rather than the Aristotelian studies still pursued at the ancient universities: Thy Colledg, Gresham, shall hereafter Be the whole world’s Universitie, Oxford and Cambridge are our laughter; Their learning is but Pedantry. -

The Unilateral Twin Pivot Grasshopper Escapement

NAWCC Chapter 161 Horological Science Newsletter 2014-1 www.hsn161.com THE UNILATERAL TWIN PIVOT GRASSHOPPER ESCAPEMENT David Heskin. 16th November 2013 All currently known written, illustrated and/or physical evidence attributable to John ‘Longitude’ Harrison (1693-1776) indicates that he invented and constructed three configurations of the grasshopper escapement: (1) The twin pivot. Almost certainly the first grasshopper escapement invented by Harrison and the first to be realised in physical form within his Brocklesby Park tower clock. The entry and exit pallet arms and their paired composers are mounted upon separate pivots, located to either side of the escapement frame arbor (crutch arbor) axis. This configuration could, therefore, be referred to as a ‘bilateral twin pivot’ or ‘BTP’ grasshopper escapement. Recent analysis1 has revealed that the deliberate incorporation of matching entry and exit start of impulse torque arms and matching entry and exit end of impulse torque arms is not only possible and arguably desirable, but is also of invaluable assistance during the geometrical design process. (2) The single pivot 2. Created by Harrison for his early wooden longcase regulators and his final land-based regulator, now commonly referred to as the ‘RAS Regulator’. Optimised in his 1775 manuscript ‘Concerning Such Mechanism…’ (CSM)3 and an untitled escapement illustration, catalogued by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers as ‘MS3972/3’. The entry and exit pallet arms and both composers share a single pivot, located on the entry side of the escapement frame arbor axis. All realistic single pivot grasshopper escapement geometries unavoidably incorporate mismatched torque arms and asymmetrical entry versus exit impulse. -

2. Descriptive Astronomy (“Astronomy Without a Telescope”)

2. Descriptive Astronomy (“Astronomy Without a Telescope”) http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/astropix.html • How do we locate stars in the heavens? • What stars are visible from a given location? • Where is the sun in the sky at any given time? • Where are you on the Earth? An “asterism” is two stars that appear To be close in the sky but actually aren’t In 1930 the International Astronomical Union (IAU) ruled the heavens off into 88 legal, precise constellations. (52 N, 36 S) Every star, galaxy, etc., is a member of one of these constellations. Many stars are named according to their constellation and relative brightness (Bayer 1603). Sirius α − Centauri, α-Canis declination less http://calgary.rasc.ca/constellation.htm - list than -53o not Majoris, α-Orionis visible from SC http://www.google.com/sky/ Betelgeuse https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Messier_objects (1758 – 1782) Biggest constellation – Hydra – the female water snake 1303 square degrees, but Ursa Major and Virgo almost as big. Hydrus – the male water snake is much smaller – 2243 square degrees Smallest is Crux – the Southern Cross – 68 square degrees Brief History Some of the current constellations can be traced back to the inhabitants of the Euphrates valley, from whom they were handed down through the Greeks and Arabs. Few pictorial records of the ancient constellation figures have survived, but in the Almagest AD 150, Ptolemy catalogued the positions of 1,022 of the brightest stars both in terms of celestial latitude and longitude, and of their places in 48 constellations. The Ptolemaic constellations left a blank area centered not on the present south pole but on a point which, because of precession, would have been the south pole c. -

The Magazine of Corpus Christi College

8 0 0 2 s a m l e a h c i M 6 1 e u s s I The magazine of Corpus Christi College Cambridge SttuarrttLaiing PaullWarrrren CorrpussCllocck FiirrssttTellephone New Mastterr New Burrsarr unveiilled Campaiign Contents 3 The Master’s Introduction Stuart Laing, Master 4 Stuart Laing takes up Mastership 8 The Office of Treasurer appointed 10 The Corpus Clock 12 Paul Warren, Bursar 14 Nick Danks, Director of Music 16 Alumni Fund & Telephone Campaign 18 Christopher Kelly: Attila the Hun 19 Paul Mellars receives an award 20 John Hatcher: The Black Death 21 Concert dates, for Ryan Wigglesworth 22 Twenty five years of the Admission of women 26 Student summer internship 27 New Junior Common Room Editor: Liz Winter Managing editor: Latona Forder-Stent Assistant editor: Lucy Gowans Photographers: Philip Mynott Andisheh Photography (Andisheh Eslamboil m2000) Stephen E Gross: Atllia the Hun Jeremy Pembrey: Corpus Clock Alexander Leiffheidt ( m2001): John Hatcher Greg E J Dickens: Chapel Organ Dr Marina Frasca-Spada Nigel Luckhurst: Ryan Wigglesworth Manni Mason Photography: Paul Mellars Jet Photographic Eden Lilley Photography Occasional Photography Produced by Cameron Design & Marketing Ltd www.cameronacademic.co.uk Master’s Introduction Dear Alumni and friends of Corpus, Gerard Duveen 4 March 1951 – 8 Nov 2008 I write having taken up the Mastership just three weeks ago. I am naturally delighted – and honoured – The Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi are to be here, at a desk looking out into New Court where sad to announce the death of Dr Gerard so many of my distinguished predecessors have Duveen, Fellow of the College and Reader in sat before. -

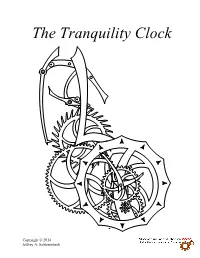

Tranquility Clock Kit and Plan Manual

The Tranquility Clock Copryight © 2014 Jeffrey A. Schierenbeck Introduction For hundreds of years, mechanical clocks have served as functional timekeepers. During that time, clocks have also been treasured for their artistic and aesthetic value. For most clocks, the artistry involves the shape and ornamentation of the clock’s exterior case. However, these cases hide the inner beauty of the clock–the clockwork mechanism. The Tranquility clock is a wooden gear clock that is a functional timekeeper with an open frame which exposes its mechanical elements. All the moving parts are clearly visible. It is intriguing to watch as the seconds and minutes tick away. Of particular interest is its ‘grasshopper’ escapement. It is based on the famous escapement which was developed by John Harrison. In the late 1700's, Harrison devised the grasshopper escapement in his quest to make an accurate, seaworthy clock and claim the “Longitude Prize”. The goal of his articulated escapement was to eliminate sliding friction at the pallets, which was a significant source of error in the days when effective lubrication had not been developed. It is enjoyable to see and hear this clock running. However, the most enjoyable part of this clock is the satisfaction gained by assembling the clock yourself, perhaps adding your own creative touches. And, through the process of building the clock, you will gain an understanding of the principles that govern how a clock works, including the operation of the unique grasshopper escapement. We truly hope you enjoy building your clock. Please contact us if there is any way that we can help you with your clockmaking project. -

Moon-Earth-Sun: the Oldest Three-Body Problem

Moon-Earth-Sun: The oldest three-body problem Martin C. Gutzwiller IBM Research Center, Yorktown Heights, New York 10598 The daily motion of the Moon through the sky has many unusual features that a careful observer can discover without the help of instruments. The three different frequencies for the three degrees of freedom have been known very accurately for 3000 years, and the geometric explanation of the Greek astronomers was basically correct. Whereas Kepler’s laws are sufficient for describing the motion of the planets around the Sun, even the most obvious facts about the lunar motion cannot be understood without the gravitational attraction of both the Earth and the Sun. Newton discussed this problem at great length, and with mixed success; it was the only testing ground for his Universal Gravitation. This background for today’s many-body theory is discussed in some detail because all the guiding principles for our understanding can be traced to the earliest developments of astronomy. They are the oldest results of scientific inquiry, and they were the first ones to be confirmed by the great physicist-mathematicians of the 18th century. By a variety of methods, Laplace was able to claim complete agreement of celestial mechanics with the astronomical observations. Lagrange initiated a new trend wherein the mathematical problems of mechanics could all be solved by the same uniform process; canonical transformations eventually won the field. They were used for the first time on a large scale by Delaunay to find the ultimate solution of the lunar problem by perturbing the solution of the two-body Earth-Moon problem. -

Rewarding Energy Innovation to Achieve Climate Stabilization

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 2011 Eyes on a Climate Prize: Rewarding Energy Innovation to Achieve Climate Stabilization Jonathan H. Adler Case Western University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Repository Citation Adler, Jonathan H., "Eyes on a Climate Prize: Rewarding Energy Innovation to Achieve Climate Stabilization" (2011). Faculty Publications. 656. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/656 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. \\jciprod01\productn\H\HLE\35-1\HLE101.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-MAR-11 12:33 EYES ON A CLIMATE PRIZE:REWARDING ENERGY INNOVATION TO ACHIEVE CLIMATE STABILIZATION Jonathan H. Adler* Stabilizing atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases at double their pre-in- dustrial levels (or lower) will require emission reductions far in excess of what can be achieved at a politically acceptable cost with current or projected levels of tech- nology. Substantial technological innovation is required if the nations of the world are to come anywhere close to proposed emission reduction targets. Neither tradi- tional federal support for research and development of new technologies nor tradi- tional command-and-control regulations are likely to spur sufficient innovation. Technology inducement prizes, on the other hand, have the potential to significantly accelerate the rate of technological innovation in the energy sector.