Aalborg Universitet the Challenge of Sustainable Mobility in Urban

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Udviklingsplan for Store Heddinge 2017

UDVIKLINGSPLAN FOR STORE HEDDINGE 2017 1 INDHOLD FORORD 3 INDLEDNING 4 2 INPUT FRA BORGERMØDET 6 VISION FOR STORE HEDDINGE 8 FRA KRIDT TIL KØBSTAD 9 STORE HEDDINGE - Købstad på Stevns 10 BYENS STRUKTUR 12 STORE HEDDINGES UDVIKLING 14 BYENS SÆRKENDE 16 LANDSKABET OG DE GRØNNE TRÆK 20 ANBEFALINGER TIL PLANLÆGNINGEN 34 Udviklingsplanen er udarbejdet af Stevns Kommune i samarbejde med PLANVÆRKSTEDET på basis af oplæg udarbejdet af PLAN.TXT.aps 2016 FORORD Fredag eftermiddag i Store Heddinge. Byen summer af liv, og der er gang i butikker- ne. Indkøbstravle familier krydser ned ad Algade, og en gruppe ældre har slået sig ned på Torvet med en kop kaffe. Foran Tinghuset lytter en gruppe turister til guidens fortælling om Store Heddinges kridthuse, og i Munkegårdsparken leger en skoleklas- se tagfat mellem parkens skulpturer. 3 Denne scene er, hvad udviklingsplanen for Store Heddinge handler om. Nemlig at skabe gode rammer for byliv og at ”fremtidssikre” Store Heddinge som godt sted at bo og besøge, uanset om man er ung, gammel eller midt imellem. Udviklingsplanen udstikker de overordnede linjer for, hvordan vi i fællesskab udvikler og styrker kom- munens største bysamfund. Udviklingsplanen tager afsæt i kommunens overordnede vision som lyder: ”Stevns Kommune skal være et bosætningsområde i stærk vækst. Udviklingen og markedsføringen af nye boligområder skal sikre, at kommunen vil være en proak- tiv og attraktiv bosætningskommune i forhold til hovedstadsområdet og de større bycentre”. Jeg håber, at udviklingsplanen for Store Heddinge kan være med til at synliggøre og bevare Store Heddinges mange værdier og samtidig inspirere byens borgere, inve- storer og interessenter til at udvikle og hermed ”fremtidssikre” Store Heddinge som en attraktiv købstad i Stevns Kommune. -

Oversigt Over Retskredsnumre

Oversigt over retskredsnumre I forbindelse med retskredsreformen, der trådte i kraft den 1. januar 2007, ændredes retskredsenes numre. Retskredsnummeret er det samme som myndighedskoden på www.tinglysning.dk. De nye retskredsnumre er følgende: Retskreds nr. 1 – Retten i Hjørring Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten i Aalborg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Randers Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Aarhus Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Viborg Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Holstebro Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Herning Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Horsens Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Kolding Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Esbjerg Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Sønderborg Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Odense Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Svendborg Retskreds nr. 14 – Retten i Nykøbing Falster Retskreds nr. 15 – Retten i Næstved Retskreds nr. 16 – Retten i Holbæk Retskreds nr. 17 – Retten i Roskilde Retskreds nr. 18 – Retten i Hillerød Retskreds nr. 19 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. 20 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 21 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 22 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 23 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 24 – Retten på Bornholm Indtil 1. januar 2007 havde retskredsene følende numre: Retskreds nr. 1 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Gentofte Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Gladsaxe Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Ballerup Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Hvidovre Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Rødovre Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Brøndbyerne Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Taastrup Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Tårnby Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. -

6030017 Denmark Danmark Kongerigst 6054053 Denmark G.S

Country County Title Film/Fiche # Item # Denmark Danish-Norwegian Research (Paleography) 6030017 Denmark Danmark Kongerigst 6054053 Denmark G.S. Research Papers Series D Vol 10 6030010 Denmark G.S. Research Papers Series D Vol 8 6030008 Denmark G.S. Research Papers Series D Vol 9 6030009 Denmark Genealogy Society Papers Series D16 6030017 Denmark Genealogy Society Papers Series D5 6030005 Denmark Maps, 1845-1916 68814 Denmark Military & Maritime Records 6039347 Denmark Pharmacists & Pharmacies, Catalogue, 1890 1440085 It 18 Denmark Postal Guide 6030021 Denmark Scandanavian Mission Emmigration 1852-1920 25696 Denmark WCOR-Danish Emigration 897215 It 15 Denmark WCOR-Danish Military Records 897215 It 13 Denmark WCOR-Danish Research 897215 It 14 Denmark WCOR-Denmark Emmigration 897215 It 1 Denmark WCOR-Town Records of Denmark 897215 It 12 Denmark Alborg Army Levying Rolls LAGD#56-116 1849 40418 Denmark Alborg Bislev Parish Records 1740-1883 43578 Denmark Alborg Blare Parish Records 1877-1916 408173 Denmark Alborg Census 1801 Nibe 39020 It 3 Denmark Alborg Census 1801 pt 39024 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Ars Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Fleskum Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Gislum Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Hansted Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Census 1845 Hellen Herred 39223 Denmark Alborg Conscription Records, Military, 1811 40328 Denmark Alborg Ejdrup Parish Records 1813-1866 43349 Denmark Alborg Ejdrup Parish Records 1867-1891 408173 Denmark Alborg Flejsborg Parish Records 1725-1860 43571 Denmark Alborg Lundby -

Aalborg Blev Årets Lokalafdeling 2009

Pressemeddelelse fra Danske Ølentusiaster Odense den 20. marts 2010 Aalborg blev Årets Lokalafdeling 2009 Blandt Danske Ølentusiasters mere end 50 lokalafdelinger er der hvert år en venskabelig kappestrid om at blive Årets Lokalafdeling. Efter indstillinger fra foreningens regioner udpeger Landsbestyrelsen en lokalafdeling der i løbet af året har udmærket sig ved gode og varierede tiltag og arrangementer til gavn for udbredelsen af kendskabet til øllets verden. Årets Lokalafdeling 2009 blev Lokalafdeling Aalborg, og det er der adskillige gode grunde til. Lokalafdeling Aalborg har gennem hele året haft et højt aktivitetsniveau og har haft mange og varierede aktiviteter. Der har naturligvis været spændende arrangementer for medlemmerne, men der har også været arrangementer der har bredt sig ud i det lokale byliv, og derved har formået at inddrage byens borgere i begejstringen for det gode øl. Lokalafdeling Aalborg har gjort det til en tradition at arrangere ølrejser til udlandet, og det er bestemt ikke kedelige rejsemål de har fundet indtil nu. Tjekkiet og Belgien er et par af de lande som har været mål for rejserne. På lokalafdelingens hjemmeside, http://aalborg.ale.dk, kan man følge med i lokalafdelingens afholdte aktiviteter, hvor der både kan findes fyldige referater og utallige billeder fra de mange inden- og udenlandske arrangementer. Arrangementer på Øllets Dag, den første lørdag i september, der inviterer den lokale befolkning til at opleve det gode øl, har selvfølgelig høj prioritet i lokalafdelingen, men det er også værd at nævne at et af de faste indslag på årsprogrammet er en Kvindeølsmagning – der de sidste par år har været krydret med henholdsvis smykker og blomster. -

Annual Report 1998 Unidanmark Unibank Contents

Annual Report 1998 Unidanmark Unibank Contents Summary . 6 Financial review . 8 The Danish economy . 14 Business description . 15 Retail Banking . 15 Corporate Banking . 21 Markets . 23 Investment Banking . 25 Risk management . 26 Capital resources . 33 Employees . 35 Management and organisation . 37 Accounts Accounting policies . 42 The Unidanmark Group . 44 Unidanmark A/S . 50 Unibank A/S . 55 Notes . 59 Unidanmark’s Local Boards of Shareholders . 84 Unibank’s Business Forum . 85 Branches in Denmark . 86 International directory . 88 Notice of meeting . 90 Management Supervisory Board of Unidanmark Jørgen Høeg Pedersen (Chairman) Holger Klindt Andersen Laurids Caspersen Boisen Lene Haulrik* Steffen Hvidt* Povl Høier Mogens Hugo Jørgensen Brita Kierrumgaard* Kent Petersen* Mogens Petersen Keld Sengeløv * Appointed by employees Executive Board of Unidanmark Thorleif Krarup Supervisory Board of Unibank Unibank’s Supervisory Board has the same members as the Supervisory Board of Unidanmark. In addition, as required by Danish banking legisla- tion, the Danish Minister of Business and Industry has appointed one mem- ber of the Supervisory Board of Unibank, Mr Kai Kristensen. Executive Board of Unibank Thorleif Krarup (Chairman) Peter Schütze (Deputy Chairman) Christian Clausen Jørn Kristian Jensen Peter Lybecker Henrik Mogensen Vision We are a leading financial services company in Denmark with a prominent position in the Nordic market. We ensure our shareholders a return in line with the return of the best among comparable Nordic financial services companies. Through our customer focus, efficient business processes and technology we create customer satisfaction and attract new customers. This confirms the customers in their choice of bank. Unibank is an attractive workplace where team spirit and customer focus are important criteria for individual success. -

Chapter Xxxiv Our Denmark Adventure

Chapter XXIV – Our Denmark Adventure CHAPTER XXXIV OUR DENMARK ADVENTURE Anita and me at Castle in Denmark Two years earlier Anita and I were passengers on a wonderful cruise that took us from Dover, England to most of the Baltic Capitols and then south to the Mediterranean and finally ending in Athens, Greece. From Athens, we flew back to Copenhagen, Denmark for a week’s stay before flying back home to Houston. Our first visit to Copenhagen was primarily to do genealogy research. Anita had discovered an organization called “Friends Overseas” and through their help, we met a wonderful couple, Ole and Else Frederiksen. Ole and Else invited us into their home for an authentic Danish meal, took us touring all over the City of Copenhagen and helped us in our genealogical quest. Our good fortune was to continue for on our fourth day in Copenhagen, Anita had been lucky enough to make contact with one of her second cousins, who lived in a small village just north of the city. Thanks to the modern miracle of email, our friendships with Ole and Else and Anita’s cousins have flourished. A year after our visit to Denmark, Ole and Else came to Houston. They had planned to spend a week with us and a week in New Orleans. We were having so much fun together that they decided to spend the entire two weeks with us. Our first visit to Denmark had given us a wonderful feel for Copenhagen but left us hungry to see the rest of the country. -

Politistationernes Åbningstider.Pdf

Politistationer Information om stationer og åbningstider er indhentet fra politi.dk Bornholm Københavns Politis Skjern Nærstation Hjørring Politistation Hittegodskontor Mandag kl. 15-16.45 Mandag, tirsdag og Bornholms Politigård Mandag-fredag kl. 09-14 Torsdag kl. 10-12 fredag kl. 10-15 Mandag-fredag kl. 09-14 Torsdag kl. 10-18 Københavns Politis Thisted Lokalstation Eftersøgningssektion Mandag-onsdag samt Kaas Politikontor Fyn Mandag-onsdag kl. 08-15 fredag kl. 10-14 Onsdag kl. 10-15 Torsdag kl. 09-15 Torsdag kl. 10-17 Ærø Politibutik Fredag kl. 08-14 Frederikshavn Politistation Første torsdag i hver måned Viborg Lokalstation Mandag, tirsdag og fredag kl. 15.00-17.00 Københavns Politi Mandag-onsdag samt kl. 10-15 Eftersøgningssektion fredag kl. 10-14 Torsdag kl. 10-18 Langeland Politibutik tager imod borgere, der er Torsdag kl. 10-17 Første torsdag i hver måned eftersøgt og/eller indkaldt til Brønderslev Politikontor kl. 15.00-17.00 at møde i retten. Åbent efter aftale Midt- og Vestsjælland Svendborg Politistation Hobro Politistation Hver torsdag kl. 15-17 Københavns Vestegn Roskilde Hovedpolitistation Mandag, tirsdag og Døgnåbent fredag kl. 10-15 Faaborg-Midtfyn Politibutik Albertslund Politigård Torsdag kl. 10-18 Første torsdag i hver måned Onsdag-lørdag kl. 07-21 Holbæk Lokalstation kl. 15.00-17.00 Søndag-tirsdag kl. 09.30-16 Mandag og onsdag kl. 10-15 Læsø Landpoliti Torsdag kl. 10-17 Tirsdag kl. 11-12 Assens Politibutik Torsdag kl. 16-17 Første torsdag i hver måned Midt-og Vestjylland Kalundborg Lokalstation kl. 15.00-17.00 Mandag og onsdag kl. 10-15 Nordjyllands Politi Holstebro Lokalstation Torsdag kl. -

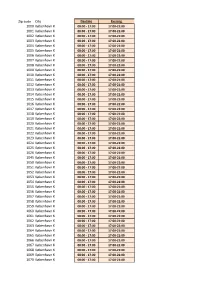

Zipcode Area Home Delivery Day and Evening.Xlsx

Zip code City Daytime Evening 1000 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1001 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1002 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1003 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1004 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1005 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1006 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1007 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1008 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1009 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1010 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1011 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1012 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1013 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1014 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1015 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1016 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1017 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1018 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1019 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1020 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1021 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1022 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1023 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1024 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1025 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1026 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1045 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1050 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1051 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1052 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1053 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1054 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1055 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1056 København K 08:00 - 17:00 17:00-21:00 1057 København K 08:00 - 17:00 -

Guloggratis Print Prisliste 2021

9990 Skagen 9982 Ålbæk 9850 9881 Hirtshals Bindslev 9981 Jerup 9970 Strandby 9800 9870 Hjørring Sindal 9900 Frederikshavn 9830 9480 9760 Tårs Løkken Vrå 9750 9300 Øster-Vrå Sæby 9740 9493 9700 Jerslev J 9352 9492 Saltum Brønderslev Dybvad Blokhus 9490 9352 9330 Pandrup Tylstrup 9320 Dronninglund 9440 9381 Hjallerup GulogGratis Aabybro Sulsted 9340 Prisliste 2021 9430 Asaa 9460 Vadum 7730 7741 Brovst 9310 Hanstholm Frøstrup 9690 9400 Vodskov Fjerritslev Nørresundby 9220 9362 9370 9000 Aalborg Ø 7742 Aalborg Gandrup Hals Vesløs 9270 7700 9200 9210 Klarup Print Thisted Aalborg SV Aalborg SØ 9280 9230 Storvorde 9670 Svenstrup 9260 Løgstør 9240 Gistrup 9681 Nibe 9293 Ranum 9530 7752 Støvring Kongerslev Snedsted 7755 7950 9541 Bedsted Thy Erslev 7884 Suldrup 9520 Fur Skørping 9574 9575 Bælum 7770 7900 9600 Terndrup Vestervig Nykøbing 9640 Aars Farsø 7960 7980 9610 9510 Karby Vils Nørager Arden 9560 7970 Hadsund 7760 Redsted 7870 7680 Hurup Thy Roslev Thyborøn 7990 9631 9620 Øster-Assels Gedsted Aalestrup 7790 9500 8970 7673 Thyholm Hobro 9550 Havndal Harboøre 7860 Mariager Spøttrup 9632 8832 Møldrup 8983 7840 Skals Gjerlev J Højslev 8990 Fårup 8981 7800 8831 Spentrup 8950 7620 Skive Ørsted Lemvig Løgstrup 8830 8585 7850 Tjele 8920 8930 8961 Glesborg 7600 7830 Stoholm Randers NV Randers NØ Allingåbro Struer Vinderup 8900 Udkommer 7650 7560 Randers 8586 Ørum Djurs Bøvlingbjerg 7660 8963 8581 8500 Hjerm 8800 8960 Grenaa Bækmarksbro Viborg 8940 Randers SØ Auning Nimtofte Randers SV 8550 8850 8870 Ryomgård 7570 Bjerringbro 8860 Langå 8570 med: 7500 -

2014 Annual Report

annual report │ 2014 a letter from the president It is an honor and a privilege addition was made possible by 1. StRAtEGIC PLANNING to serve on the Board for the the generous donation of museum The current plan used by the Museum of Danish America. patrons. It is with such generous museum covers the years Serving with so many people who contributions from these folks 2011-2015. This plan has are focused on the preservation of that we are able to continue the provided and continues to Danish culture and history is truly preservation of Danish culture and provide a “roadmap,” if you a pleasure! It has been great to heritage. I encourage you to read will, for guiding the activities have the opportunity to work with the section of this Annual Report of the museum. The technical so many talented staff that makes regarding Collections, authored term for strategic planning is the museum what it is today. It is by Angela Stanford, Curator of as follows: An organization’s due to the efforts of the staff and Collections/Registrar. process of defining its strategy, volunteers that the museum has or direction, and making been able to succeed over the I certainly do not wish to “steal decisions on allocating its last 30+ years. However, equally the thunder” of the additional resources to pursue the important are the generous staff who are also providing strategy. A new plan will be financial contributions, both large updates in this Annual Report. developed during 2015 that will and small, that have been made Therefore, I would encourage you be put into action for the 2016- to the museum over the years. -

Vitamin D in Plants Occurrence, Analysis and Biosynthesis

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Sep 23, 2021 Vitamin D in plants Occurrence, analysis and biosynthesis Jäpelt, Rie Bak Publication date: 2011 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Jäpelt, R. B. (2011). Vitamin D in plants: Occurrence, analysis and biosynthesis . DTU Food. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Vitamin D in plants – occurrence, analysis and biosynthesis Rie Bak Jäpelt PhD Thesis 2011 Vitamin D in plants Occurrence, analysis and biosynthesis PhD thesis Rie Bak Jäpelt Division of Food Chemistry National Food Institute Technical University of Denmark 2011 Preface This PhD study was conducted from 2008 to 2011 at the Division of Food Chemistry, National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark. The project was financially supported by Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, Directorate for Food, Fisheries and Agri Business (3304-FVFP-07-774-02) and Technical University of Denmark. -

Fsc® Chain of Custody Certificate

® FSC CHAIN OF CUSTODY CERTIFICATE Certificate no.: Initial certification date: Valid: DNV-COC-001023 08 January 2015 08 January 2020 – 07 January 2025 Issue Number: 6 The validity of this certificate shall be verified on www.info.fsc.org This is to certify that the Bygma Gruppen A/S Transformervej 12, 2860 Søborg, Denmark and the sites as mentioned in the appendix accompanying this certificate has been found to conform to FSC standard: FSC-STD-40-003, FSC-STD-40-004 This certificate is valid for the following scope: Wholesale of solid wood and Engineered wood products, FSC 100% and FSC Mix, Transfer system A list of the certificated products can be obtained from the FSC database, www.info.fsc.org This certificate itself does not constitute evidence that a particular product supplied by the certificate holder is FSC-certified (or FSC Controlled Wood). Products offered, shipped or sold by the certificate holder can only be considered covered by the scope of this certificate when the required FSC claim is clearly stated on invoices and shipping documents. Place and date: For the issuing office: Solna, 03 February 2021 DNV GL - Business Assurance Elektrogatan 10, 171 54, Solna, Sweden Ann-Louise Pått Management Representative Lack of fulfilment of conditions as set out in the Certification Agreement may render this Certificate invalid.This certificate is the property of DNV GL Business Assurance Sweden AB and must be returned on request ACCREDITED UNIT: DNV GL Business Assurance Sweden AB, Elektrogatan 10, 171 54 Solna, Sweden - TEL: +46