0 the Bedouin of Palestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Practices of Irrigation Water Pricing

\J4S ILI(QQ POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Public Disclosure Authorized Efficiency and Equity Pricing of water may affect allocation considerations by Considerations in Pricing users. Efficiency isattainable andAllocating Irrigation wheneverthe pricing method affectsthe demandfor Public Disclosure Authorized Water irrigation water. The extent to which water pricing methods can affect income Yacov Tsur redistributionis limited.To Ariel Dinar affect incomeinequality, a water pricing method must include certain forms of water quantity restrictions. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The WorldBank Agricultureand Natural ResourcesDepartment Agricultural Policies Division May 1995 POLICYRESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Summary findings Economic efficiency has to do with how much wealth a inefficient allocation. But they are usually easier to given resource base can generate. Equity has to do with implement and administer and require less information. how that wealth is to be distributed in society. Economic The extent to which water pricing methods can effect efficiency gets far more attention, in part because equity income redistribution is limited, the authors conclude. considerations involve value judgments that vary from Disparities in farm income are mainly the result of person to person. factors such as farm size and location and soil quality, Tsur and Dinar examine both the efficiency and the but not water (or other input) prices. Pricing schemes equity of different methods of pricing irrigation water. that do not involve quantity quotas cannot be used in After describing water pricing practices in a number of policies aimed at affecting income inequality. countries, they evaluate their efficiency and equity. The results somewhat support the view that water In general they find that water use is most efficient prices should not be used to effect income redistribution when pricing affects the demand for water. -

The Good Samaritan Inn 55 NATIONAL PARKS and NATURE Mosaic Museum RESERVES

BUY AN ISRAEL NATURE AND PARKS AUTHORITY SUBSCRIPTION FOR UNLIMITED FREE ENTRY TO The Good Samaritan Inn 55 NATIONAL PARKS AND NATURE Mosaic Museum RESERVES. A lioness from the Gaza mosaic Rules of Conduct ■ Do not harm the antiquities: Do not carve on them, walk on them or pour water on them. ■ Do not collect “souvenirs” from remains scattered in the area. ■ Do not enter places that are off-limits for visitors. Nearby Sites: ■ Do not cross fences or roll stones. ■ Please keep the area clean. Qumran Location of the Good Samaritan Inn Mosaic Museum National Park about 25 minutes’ drive The museum is on the southern side of the Jerusalem–Jericho road (road 1) between kilometer markers 80 and 81. The interchange affords easy access from whichever direction you approach. To reserve a guided tour for a group, email: You Enot Tsukim are here Nature Reserve [email protected] about 25 minutes’ drive Hours: Daily from 8:00 to 17:00. En Prat During winter time, the site closes one hour earlier. Nature Reserve On Fridays and holiday eves, the site closes one hour earlier. about 20 minutes’ drive Entry is permitted up to one hour before closing. Text: Ya‘acov Shkolnik Translation: Miriam Feinberg Vamosh 6.18 Photos: Israel Nature and Parks Authority Archive; Ya‘acov Shkolnik; Tal Romano; Amir Aloni Production: Adi Greenbaum www.parks.org.il I *3639 I © Israel Nature and Parks Authority The Good Samaritan Inn, Tel: 02-6338230 established on the initiative of the archaeologist Dr. Yitzhak Welcome to the Magen, who served as the head of the Judea and Samaria Inn of the Good Samaritan Archaeology Unit. -

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Report: T I O 28N FebruaryS – 6 March 2007 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 28 February – 6 March 2007 Of note this week The IDF imposed a total closure on the West Bank during the Jewish holiday of Purim between 2 – 5 March. The closure prevented Palestinians, including workers, with valid permits, from accessing East Jerusalem and Israel during the four days. It is a year – the start of the 2006 Purim holiday – since Palestinian workers from the Gaza Strip have been prevented from accessing jobs in Israel. West Bank: − On 28 February, the IDF re-entered Nablus for one day to continue its largest scale operation for three years, codenamed ‘Hot Winter’. This second phase of the operation again saw a curfew imposed on the Old City, the occupation of schools and homes and house-to-house searches. The IDF also surrounded the three major hospitals in the area and checked all Palestinians entering and leaving. According to the Nablus Municipality 284 shops were damaged during the course of the operation. − Israeli Security Forces were on high alert in and around the Old city of Jerusalem in anticipation of further demonstrations and clashes following Friday Prayers at Al Aqsa mosque. Due to the Jewish holiday of Purim over the weekend, the Israeli authorities declared a blanket closure from Friday 2 March until the morning of Tuesday 6 March and all major roads leading to the Old City were blocked. -

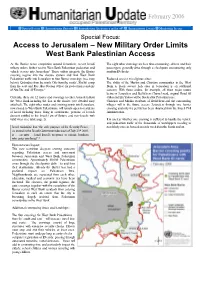

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

NABI SAMWIL Saint Andrew’S Evangelical Church - (Protestant Hall) Ramallah - West Bank - Palestine 2018

About Al-Haq Al-Haq is an independent Palestinian non-governmental human rights organisation based in Ramallah, West Bank. Established in 1979 to protect and promote human rights and the rule of law in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), the organisation has special consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council. Al-Haq documents violations of the individual and collective rights of Palestinians in the OPT, regardless of the identity of the perpetrator, and seeks to end such breaches by way of advocacy before national and international mechanisms and by holding the violators accountable. The organisation conducts research; prepares reports, studies and interventions on the breaches of international human rights and humanitarian law in the OPT; and undertakes advocacy before local, regional and international bodies. Al-Haq also cooperates with Palestinian civil society organisations and governmental institutions in order to ensure that international human rights standards are reflected in Palestinian law and policies. The organisation has a specialised international law library for the use of its staff and the local community. Al-Haq is also committed to facilitating the transfer and exchange of knowledge and experience in international humanitarian and human rights law on the local, regional and international levels through its Al-Haq Center for Applied International Law. The Center conducts training courses, workshops, seminars and conferences on international humanitarian law and human rights for students, lawyers, journalists and NGO staff. The Center also hosts regional and international researchers to conduct field research and analysis of aspects of human rights and IHL as they apply in the OPT. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

Discussion of Objections on E1 Plans Scheduled for October 4 and 18

Subscribe Past Issues Translate RS If you can't see this alert properly, view this email in your browser Discussion of Objections on E1 Plans Scheduled for October 4 and 18 02 September 2021 On August 29, the Supreme Planning Council of the Civil Administration issued new dates for convening the discussion on objections to the E1 plans for 3412 housing units: October 4 and 18. Having originally attempted to schedule the discussion for August 9, the planning council postponed it, claiming it was unable to find a mutually convenient time for all parties involved. The discussion of objections constitutes one of the final stages in the plans' approval. While it is unclear who initiated the discussion, it is unlikely to have happened without the knowledge and approval of both the Israeli Minister of Defense and Prime Minister. Advancement of the plans comes just days after Israeli Prime Minister Bennett met with US President Biden in Washington where Biden underscored the necessity to refrain from measures which inflame tensions and reaffirmed his support for the two-state solution. Construction in E1 has long been regarded as a death blow to the two-state framework and threatens to displace roughly 3,000 Palestinians living in small Bedouin communities in the area, including Khan al-Ahmar. For years, the E1 plans had been frozen due to strong bipartisan US and international opposition until former Prime Minister Netanyahu promoted the plans last year as part of his 2020 re-election bid and within the framework of the government's accelerated steps towards de-facto annexation. -

99.8% of State Lands Allocated in the West Bank Were Given to Israelis; Palestinians Were Given Almost Nothing

State Land Allocation in the West Bank—For Israelis Only, July 2018 99.8% of state lands allocated in the West Bank were given to Israelis; Palestinians were given almost nothing Following a request under the Freedom of Information Act submitted by Peace Now and the Movement for Freedom of Information (and after refusing to give the information and a two-and-a-half year delay), the Civil Administration's response was received: 99.76% (about 674,459 dunams) of state land allocated for any use in the Occupied West Bank was allocated for the needs of Israeli settlements. The Palestinians were allocated, at most, only 0.24% (about 1,625 dunams). Some 80% of the allocations to Palestinians (1,299 dunams) were for the purpose of establishing settlements (669 dunams) and for the forced transfer of Bedouin communities (630 dunams). Only 326 dunams at most were allocated without strings for the benefit of Palestinians, and at least 121 of those dunams are currently in Area B under Palestinian control. Most of the allocations to the Palestinians (about 53%) were made prior to the 1995 Interim Agreement (the Oslo II Agreement, in which the West Bank was divided into Areas A, B and C, and transferred control over 40% of the West Bank to the Palestinian Authority). The High Court of Justice is currently facing the issue of the evacuation of the Palestinian village of Al-Khan al- Ahmar, which the state wants to demolish and expel its residents to another area. The residents of the village are asking the High Court of Justice to stop the evacuation until the Civil Administration discusses the detailed construction plan they prepared for the village's approval, which the state has refused to consider. -

The Absentee Property Law and Its Implementation in East Jerusalem a Legal Guide and Analysis

NORWEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCIL The Absentee Property Law and its Implementation in East Jerusalem A Legal Guide and Analysis May 2013 May 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Consulting legal advisor: Adv. Sami Ershied Language editor: Risa Zoll Hebrew-English translations: Al-Kilani Legal Translation, Training & Management Co. Cover photo: The Cliff Hotel, which was declared “absentee property”, and its owner Ali Ayad. (Photo by: Mohammad Haddad, 2013). This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non-governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Talia Sasson, Adv. Daniel Seidmann and Adv. Raphael Shilhav for their insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 8 2. Background on the Absentee Property Law .................................................. 9 3. Provisions of the Absentee Property Law .................................................... 14 3.1 Definitions ....................................................................................................................