MLP Increasing Conflicts on National Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion in the Works of Heinrich Heine

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1946 Religion in the works of Heinrich Heine Ellen Frances DeRuchie University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation DeRuchie, Ellen Frances. (1946). Religion in the works of Heinrich Heine. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/1040 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELIGION IN THE WORKS OF R- ---- II .,; - --- stoclcton ~·- 1946 =------- :-;---- A Thesis submitted to the Department of Modern Lanugages Col~ege of ·the Pacific :~ - In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree ot Master of Arts DEPOSITED IN THE C01.LEGE LIBRARY: DA'l'ED: Librarian CONTENTS co---- Chapter Page Introduction ••••••••••••• ·• ........... ., .......... • !v I Heine 1 a Jewish Background •••••••••• , ••• , •• l II Some Aspects of Judaism in Heine •••••••••• 12 III Heine t s Baptism ~ ........ * •- .................. , "' 21 IV Some Reflections on Christianity ••••·••••• 26 V Some Re:Clec t:l.ons on Protestantism ••••••••• 31 VI State Religion • •• •- •• • .... • •••••.• ._ •• •-• .•• -•• 38 VII Some Reflections on Catholicism ••••••.••••• 42 VIII Catholicism and Art •••••••••••••••••••••••• 54 IX A Pantheistic Interlude •••••••••••••••••••·61 X Sa~nt Simonism -• • .... •• .••• • • •- .·-· ............. 67 XI The .Religion of Freedom .................... '72 XII Heine's Last Days ••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7S Bib 11 ogr aphy ••• _•.••• ·• ••••••• -• .- • -·· • .., ••• -• • -• • • • 85 lv INTRODUCTION A Word about Heinrich Heine The life of Heinrich Heine presents many eontradictl.ons. -

A Civic Profession of Faith: Rousseau's and Nationalism

4 A civic profession of faith: Rousseau’s and nationalism When Heinrich Heine, the German poet, visited Italy in 1828 he noted in his diary: It is as if World History is seeking to become spiritual … she has a great task. What it is? It is emancipation. Not just the emancipation of the Irish, the Greeks, the Jews and the Blacks of the West Indies. No, the emancipation of the whole world, especially in Europe, where the peoples have reached maturity. (Heine quoted in Gell 1998: 13) In seeking national self-determination Heine was preaching a new doctrine, one which had been unknown a couple of centuries before. Elie Kedouri observed – perhaps not entirely accurately – that ‘Nationalism is a political doctrine invented in Europe at the beginning of the Nineteenth Century’ (Kedouri 1960: 1). This might have been an exaggeration but Kedouri had a point. Nationalism is not only regarded as a relatively recently established ideology, it is also regarded as a fatherless doctrine, without the illustrious intellectual ancestry which characterises socialism, liberalism, and even conservatism. Nationalism, it is asserted, lacks a coherent philosophical basis and does not have an intellectual founding father. In Benedict Anderson’s words: ‘unlike most other isms, nationalism has never produced its great thinkers; no Hobbeses, Tocquevilles, Marxes or Webers’ (Anderson 1981: 5).1 This view seemingly ignores the theory of nationalism developed by Rousseau before the nineteenth century.2 Rousseau is rarely given full credit for his contribution to the development of the doctrine of nationalism. Unmentioned by Gellner (1983; 1996) and Miller (1995), Rousseau is only mentioned in passing by Anderson (1983) and Hobsbawm (1991). -

GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 by CLAUDIA MAREIKE

ROMANTICISM, ORIENTALISM, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY: GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 By CLAUDIA MAREIKE KATRIN SCHWABE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Claudia Mareike Katrin Schwabe 2 To my beloved parents Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisory committee chair, Dr. Barbara Mennel, who supported this project with great encouragement, enthusiasm, guidance, solidarity, and outstanding academic scholarship. I am particularly grateful for her dedication and tireless efforts in editing my chapters during the various phases of this dissertation. I could not have asked for a better, more genuine mentor. I also want to express my gratitude to the other committee members, Dr. Will Hasty, Dr. Franz Futterknecht, and Dr. John Cech, for their thoughtful comments and suggestions, invaluable feedback, and for offering me new perspectives. Furthermore, I would like to acknowledge the abundant support and inspiration of my friends and colleagues Anna Rutz, Tim Fangmeyer, and Dr. Keith Bullivant. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my family, particularly my parents, Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe, as well as to my brother Marius and his wife Marina Schwabe. Many thanks also to my dear friends for all their love and their emotional support throughout the years: Silke Noll, Alice Mantey, Lea Hüllen, and Tina Dolge. In addition, Paul and Deborah Watford deserve special mentioning who so graciously and welcomingly invited me into their home and family. Final thanks go to Stephen Geist and his parents who believed in me from the very start. -

Zukas on Hazan, 'A History of the Barricade'

H-Socialisms Zukas on Hazan, 'A History of the Barricade' Review published on Thursday, October 20, 2016 Eric Hazan. A History of the Barricade. London: Verso, 2015. 144 pp. $17.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-78478-125-5. Reviewed by Alex Zukas (College of Letters and Sciences, National University)Published on H- Socialisms (October, 2016) Commissioned by Gary Roth Barricades In his book, Eric Hazan presents a brief and readable historical survey of a long-standing symbol of insurrectionary urban politics, the barricade. While there are moments of serious analysis, he takes a narrative approach to the historical phenomenon of the barricade in short, breezy chapters (ten to fifteen pages on average) and embeds his analysis in stories about the barricades from protagonists and antagonists. Besides some key secondary sources and documentary collections, the major source for his stories is the memoirs and writings of French public figures and authors such as Cardinal de Retz, François-René de Chateaubriand, Louis Blanc, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, Alexis de Tocqueville, Mikhail Bakunin, and Auguste Blanqui. The verve of Hazan’s writing and that of his sources contribute to the feeling of being an eyewitness to unfolding events. This is his intent: “it is these heroes and heroines that I have tried to being back to life from the anonymity into which official history has cast them” and to make this history “a source of inspiration for those unresigned to the perpetuation of the existing order” (p. x). It is a partisan but not an uncritical history in which the author spends a large part of each chapter on the battle tactics of the barricade builders and the armies that assailed them. -

About Jan Wagner Jan Wagner Was Born 1971 in Hamburg and Has

About Jan Wagner Jan Wagner was born 1971 in Hamburg and has been living in Berlin since 1995. He is a poet, a translator of Anglo-American poetry (Charles Simic, James Tate, Simon Armitage, Matthew Sweeney, Jo Shapcott, Robin Robertson, Michael Hamburger, Dan Chiasson and many others), a literary critic (Frankfurter Rundschau, Der Tagesspiegel and others) and has been, until 2003, a co-publisher of the international literature box Die Aussenseite des Elementes („The Outside of the Element“). Apart from numerous appearances in anthologies and magazines, he has published the poetry collections Probebohrung im Himmel („A Trial Drill in the Sky“; Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2001), Guerickes Sperling („Guericke’s Sparrow“, Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2004), Achtzehn Pasteten (“Eighteen Pies”, Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2007) and Australien (“Australia”, Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2010) and, as translator and editor, collections of selected poems by James Tate, Der falsche Weg nach Hause (“The Wrong Way Home”, Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2004), Matthew Sweeney, Rosa Milch (“Pink Milk”, Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2008) and Simon Armitage („Zoom!“, 2011). With the poet Björn Kuhligk he edited the comprehensive anthologies of young German language poetry Lyrik von Jetzt. 74 Stimmen („Poetry of Now. 74 voices“, Dumont Verlag, Cologne 2003) and its sequel Lyrik von Jetzt zwei. 50 Stimmen (Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2008) and co-operated on the book Der Wald im Zimmer. Eine Harzreise (“A Forest Inside the Room. A Journey Across the Harz Mountains”, Berliner Taschenbuch Verlag, Berlin 2007), an hommage to Heinrich Heine. A selection of his essays, Die Sandale des Propheten. Beiläufige Prosa (“The Prophet’s Sandal. Incidental Prose”), was published 2011 by Berlin Verlag. -

Pericles S. Vallianos I. Romanticisms

ROMANTICISM AND POLITICS: FROM HEINRICH HEINE TO CARL SCHMITT – AND BACK AGAIN Pericles S. Vallianos Abstract: After a reference to the debate concerning the concept of Romanticism (Lovejoy vs Wellek), the article briefly evokes certain key stances of English and French literary Romanticism. It then points to the distinguishing features of German Romanticism, namely the enlargement of the doctrine into an integral metaphysics with the concept of the “organic state” at its core (A. Müller). The critique of political Romanticism by two revolutionary democrats (H. Heine and A. Ruge) is then presented. The article closes with a critique of C. Schmitt’s interpretation of political Romanticism. I. Romanticisms Romanticism was a cultural movement which put European civilization on new tracks. It is, however, notoriously difficult to define – so ramified are its particular forms and branches. The term “Romantic” as a marker of a new age of “progressive universal poetry” superseding the anti-poetic Classicism of the Enlightenment was invented by Friedrich Schlegel1 and elaborated further by his brother, August Wilhelm. In France it emerged after the Bourbon restoration and established itself towards the end of the 1820s and especially in the wake of the notorious “Hernani battle” of 1830.2 Capitalizing on this continuing difficulty a whole century and more after Romanticism’s first stirrings, Arthur O. Lovejoy argued, in a landmark article published in 1924, that we must give up striving for a general definition. In his view, there is no one internally cohering Romanticism. The concept must not be “hypostatized” as if it referred to a single real entity “existing in nature”.3 What we have instead is a variety of local and specific cultural and literary phenomena to which, for the purposes of brevity and broad-stroke classification, a common name is appended. -

THE POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY of JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU the Impossibilityof Reason

qvortrup.cov 2/9/03 12:29 pm Page 1 Was Rousseau – the great theorist of the French Revolution – really a Conservative? THE POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY OF JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU This original study argues that the author of The Social Contract was a constitutionalist much closer to Madison, Montesquieu and Locke than to revolutionaries. Outlining his profound opposition to Godless materialism and revolutionary change, this book finds parallels between Rousseau and Burke, as well as showing that Rousseau developed the first modern theory of nationalism. The book presents an inte- grated political analysis of Rousseau’s educational, ethical, religious and political writings. The book will be essential readings for students of politics, philosophy and the history of ideas. ‘No society can survive without mutuality. Dr Qvortrup’s book shows that rights and responsibilities go hand in hand. It is an excellent primer for any- one wishing to understand how renewal of democracy hinges on a strong civil society’ The Rt. Hon. David Blunkett, MP ‘Rousseau has often been singled out as a precursor of totalitarian thought. Dr Qvortrup argues persuasively that Rousseau was nothing of the sort. Through an array of chapters the book gives an insightful account of Rousseau’s contribution to modern philosophy, and how he inspired individuals as diverse as Mozart, Tolstoi, Goethe, and Kant’ John Grey, Professor of European Political Thought,LSE ‘Qvortrup has written a highly readable and original book on Rousseau. He approaches the subject of Rousseau’s social and political philosophy with an attractively broad vision of Rousseau’s thought in the context of the development of modernity, including our contemporary concerns. -

Emma Lazarus 1849–1887

Name _____________________________ Class _________________ Date __________________ Life at the Turn of the 20th Century Biography Emma Lazarus 1849–1887 WHY SHE MADE HISTORY Poet and scholar Emma Lazarus was one of the first successful Jewish American authors. She wrote the poem engraved at the base of the Statue of Liberty. As you read the biography below, think about how Emma Lazarus’s cultural heritage influenced her life and writing. Bettmann/CORBIS © From 1880 to 1910, the face of America changed as some 18 million people immigrated to America from Europe and Asia. In 1885 a statue, 151 feet tall, was placed in New York Harbor to greet these newcomers. The statue, titled Liberty Enlightening the World, was a gift from France. Lady Liberty still stands in the harbor as a symbol of freedom and opportunity. The famous lines inscribed at the base of the statue were written by Emma Lazarus. Emma Lazarus was born in New York City in 1849. Her ancestors were among the first Jewish settlers to come to America. Her heritage made Lazarus part of a distinct Jewish upper class. Lazarus’s father was a wealthy sugar merchant, and the family lived in a fashionable neighborhood in New York City. Lazarus was educated at home. She studied the classics of ancient Greece and Rome as well as the writers of her time. Her father recognized young Emma’s talent as a writer and encouraged her work. Lazarus was just 17 when she privately published her first book, titled Poems and Translations Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Seventeen. -

Material and Social Relations in Friedrich Von Hardenberg's Heinrich Von Afterdingen

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2008 Material and Social Relations in Friedrich von Hardenberg's Heinrich von Afterdingen Robert Earl Mottram The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mottram, Robert Earl, "Material and Social Relations in Friedrich von Hardenberg's Heinrich von Afterdingen" (2008). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 650. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/650 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MATERIAL AND SOCIAL RELATIONS IN FRIEDRICH VON HARDENBERG'S HEINRICH VON AFTERDINGEN By ROBERT EARL MOTTRAM B.A. in German, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2006 Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures – German The University of Montana June 2008 ______________________________ Chairperson ______________________________ Dean of Graduate School ______________________________ Date MATERIAL AND SOCIAL RELATIONS IN FRIEDRICH VON HARDENBERG'S HEINRICH VON -

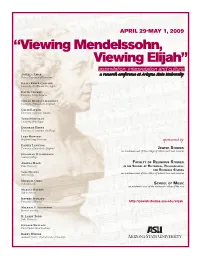

“Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah”

APRIL 29-MAY 1, 2009 “Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah” assimilation, interpretation and culture Ariella Amar a rreses eearcharch cconferenceonference atat ArizonaArizona StateState UniversityUniversity Hebrew University of Jerusalem Julius Reder Carlson University of California, Los Angeles David Conway University College London Sinéad Dempsey-Garratt University of Manchester, England Colin Eatock University of Toronto, Canada Todd Endelman University of Michigan Deborah Hertz University of California, San Diego Luke Howard Brigham Young University sponsored by Daniel Langton University of Manchester, England JEWISH STUDIES an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Jonathan D. Lawrence Canisius College Angela Mace FACULTY OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES Duke University IN THE SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL, PHILOSOPHICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES Sara Malena Wells College an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Michael Ochs Ochs Editorial SCHOOL OF MUSIC an academic unit of the Herberger College of the Arts Marcus Rathey Yale University Jeffrey Sposato University of Houston http://jewishstudies.asu.edu/elijah Michael P. Steinberg Brown University R. Larry Todd Duke University Donald Wallace United States Naval Academy Barry Wiener Graduate Center, City University of New York Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah: assimilation, interpretation and culture a research conference at Arizona State University / April 29 – May 1, 2009 Conference Synopsis From child prodigy to the most celebrated composer of his time: Felix Mendelssohn -

The Laws of the Sabbath (Poetry): Arendt, Heine, and the Politics of Debt

Honig_production read v3 (clean) (Do Not Delete) 6/17/2015 10:46 PM The Laws of the Sabbath (Poetry): Arendt, Heine, and the Politics of Debt Bonnie Honig* I. Heine’s Hidden Tradition ......................................................................................... 464 II. Greek, Jewish, and Arabian Tales: Taking Sabbath ........................................... 466 III. Making Sabbath ....................................................................................................... 470 IV. Sabbath-Power .......................................................................................................... 473 V. The Day of (W)rest ................................................................................................... 477 VI. Fantasy and World-Making .................................................................................... 480 “You are not a loan.” 1 Glossolalia is a foreign, natural, or magical (non)language, a kind of linguistic state of exception in which the normal rules or experience of signification are suspended and something like the true nature of linguistic practice (or its complete upheaval!) is made apparent.2 In what follows, I use the figures glossolalia and the state of exception, to interrogate Hannah Arendt’s assessment of Heinrich Heine and her reading of his Sabbath poetry in her famous essay The Jew as Pariah: A Hidden Tradition.3 For Arendt, Heine is caught up with the illusory promise of nature, which renders some of his work practically glossolalic and leaves him stuck in -

Of Heinrich Heine

ABOUT TONIGHT’S ARTISTS Donald George is an Associate Professor of Vocal Music at the Crane School of Music – SUNY Potsdam and an Honored Professor at Shenyang Con- servatory in China. He has also taught at the Bavarian Theater Academy in Munich and sung at the Paris Opera, La Scala , Royal Opera of Brussels, Kennedy Center, the State Operas of Berlin, Hamburg and Vienna, the Festivals of Salzburg, Buenos Aires, Jerusalem, Istanbul, Blossom USA. SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE He has sung with Leonard Bernstein, Kurt Masur, Yehudi Menuhin, Jeffry Tate and recorded Elijah, Verdi Requiem, Rossini’s Aurelieano in Palmira Beall Concert Hall Monday evening and Le Nozze di Teti e Peleo (the world premiere recording), Die Schöne Müllerin. Reviews of Donald George speak of his “pleasing tenor sound, 8:00 p.m. October 26, 2009 vocally reliable in all challenges” (Verdi Requiem-Metropolitan Opera News), “A success for La Scala all possess a superb technique, and are consummate actors…including Donald George” (Peter Grimes-Corriere THE GUEST ARTIST SERIES della Sera), Donald George provides Candide with a supple, beautiful toned lyricism-His Lament is one of the highlights of the performance (Candide-Münchner Merkur). presents Lucy Mauro is an Assistant Professor at West Virginia University. She is a graduate of the Peabody Conservatory from which she received Bachelor’s, Master’s and Doctorate degrees and where she studied with “The Old Wicked Songs” Ann Schein and Julio Esteban. She is the co-editor of Essential Two- Piano Repertoire, Essential Keyboard Trios, and other forthcoming books from Alfred Publishing.