(Phaseolus Coccineus L.) Genotypes Shows Moderate Agronomic and Genetic Variability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, James Andrew, "A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) " (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5832. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5832 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

1 Assessment of Runner Bean (Phaseolus Coccineus L.) Germplasm for Tolerance To

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital.CSIC 1 Assessment of runner bean (Phaseolus coccineus L.) germplasm for tolerance to 2 low temperature during early seedling growth 3 4 A. Paula Rodiño1,*, Margarita Lema1, Marlene Pérez-Barbeito1, Marta Santalla1, & 5 Antonio M. De Ron1 6 1 Plant Genetic Resources Department, Misión Biológica de Galicia - CSIC, P. O. Box 7 28, 36080 Pontevedra, Spain (*author for correspondence, e-mail: 8 [email protected]) 9 1 1 Key words: Cold tolerance, characterization, diversity, genetic improvement 2 3 Summary 4 The runner bean requires moderately high temperatures for optimum germination and 5 growth. Low temperature at sowing delays both germination and plant emergence, and 6 can reduce establishment of beans planted early in the growing season. The objective of 7 this work was to identify potential runner bean germplasm with tolerance to low 8 temperature and to assess the role of this germplasm for production and breeding. Seeds 9 of 33 runner bean accessions were germinated in a climate-controlled chamber at 10 optimal (17 ºC-day/15 ºC-night) and at sub-optimal (14 ºC-day/8 ºC-night) temperature. 11 The low temperature tolerance was evaluated on the basis of germination, earliness, 12 ability to grow and vigor. Differences in agronomical characters were significant at low 13 temperatures for germination, earliness, ability to grow and early vigor except for 14 emergence score. The commercial cultivars Painted Lady Bi-color, Scarlet Emperor, the 15 Rwanda cultivar NI-15c, and the Spanish cultivars PHA-0013, PHA-0133, PHA-0311, 16 PHA-0664, and PHA-1025 exhibited the best performance under cold conditions. -

Phaseolus Vulgaris (Beans)

1 Phaseolus vulgaris (Beans) Phaseolus vulgaris (Beans) dry beans are Brazil, Mexico, China, and the USA. Annual production of green beans is around 4.5 P Gepts million tonnes, with the largest production around Copyright ß 2001 Academic Press the Mediterranean and in the USA. doi: 10.1006/rwgn.2001.1749 Common bean was used to derive important prin- ciples in genetics. Mendel used beans to confirm his Gepts, P results derived in peas. Johannsen used beans to illus- Department of Agronomy and Range Science, University trate the quantitative nature of the inheritance of cer- of California, Davis, CA 95616-8515, USA tain traits such as seed weight. Sax established the basic methodology to identify quantitative trait loci (for seed weight) via co-segregation with Mendelian mar- Beans usually refers to food legumes of the genus kers (seed color and color pattern). The cultivars of Phaseolus, family Leguminosae, subfamily Papilio- common bean stem from at least two different domes- noideae, tribe Phaseoleae, subtribe Phaseolinae. The tications, in the southern Andes and Mesoamerica. In genus Phaseolus contains some 50 wild-growing spe- turn, their respective wild progenitors in these two cies distributed only in the Americas (Asian Phaseolus regions have a common ancestor in Ecuador and have been reclassified as Vigna). These species repre- northern Peru. This knowledge of the evolution of sent a wide range of life histories (annual to perennial), common bean, combined with recent advances in the growth habits (bush to climbing), reproductive sys- study of the phylogeny of the genus, constitute one of tems, and adaptations (from cool to warm and dry the main current attractions of beans as genetic organ- to wet). -

Scarlet Runner Bean, Phaseolus Coccineus

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 7 July 2014 Scarlet Runner Bean, Phaseolus coccineus Scarlet runner bean, Phaseolus coccineus, is a tender herbaceous plant native to the mountains of Mexico and Central America, growing at higher elevations than the common bean. By the 1600’s it was growing in English and early American gardens as a food plant, but now is more frequently grown as an ornamental for its showy sprays of fl owers. Unlike regular green beans (P. vulgaris) this is a perennial species, although it is usually treated as an annual. In mild climates (zones 7-11) it a short-lived perennial vine, forming tuberous roots from which new shoots sprout annually in areas with frost where it is not evergreen. In Mesoamerica the thick, starchy roots are used as food. P. coccineus looks very similar to pole beans, with dark green, heart-shaped trifoliate leaves with purple tinged veins on the undersides. The quick- growing twining vines can get up to 15 feet or more in length (although they tend to be closer to 6-8 feet in most Midwestern gardens), rambling through other vegetation, or climbing on a trellis or other support in Scarlet runner bean has typical trifoliate Scarlet runner bean growing on a tall a garden. leaves similar to regular beans. teepee. About two months after sowing plants produce scarlet red, or occasionally white, typical legume fl owers with the two lowermost petals combining into a “keel”, the uppermost petal modifi ed into a hoodlike “standard”, and the petals on the sides spreading as “wings.” Up to 20 inch-long fl owers are produced in each cluster (raceme) along the vines. -

Home Vegetable Gardening in Washington

Home Vegetable Gardening in Washington WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION • EM057E This manual is part of the WSU Extension Home Garden Series. Home Vegetable Gardening in Washington Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................1 Vegetable Garden Considerations ..................................................................................................1 Site-Specific Growing Conditions .............................................................................................1 Crop Selection .........................................................................................................................3 Tools and Equipment .....................................................................................................................6 Vegetable Planting .........................................................................................................................7 Seeds .......................................................................................................................................7 Transplants .............................................................................................................................10 Planting Arrangements ................................................................................................................14 Row Planting ..........................................................................................................................14 -

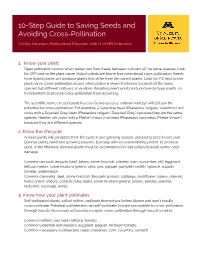

10-Step Guide to Saving Seeds and Avoiding Cross-Pollination

10-Step Guide to Saving Seeds and Avoiding Cross-Pollination Christy Marsden, Horticulture Educator with U of MN Extension 1. Know your plant Open pollination occurs when pollen can flow freely between cultivars of the same species. Look for (OP) next to the plant name. Hybrid plants are borne from intentional cross-pollination. Seeds from hybrid plants will produce plants that differ from the parent plants. Look for (F1) next to the plant name. Cross pollination occurs when pollen is shared between to plants of the same species but different cultivars or varieties. Resulting seed won’t produce true-to-type plants, so it’s important to prevent cross-pollination from occurring. The scientific name of each plant [read as Genus species ‘cultivar/variety’] will tell you the potential for cross-pollination. For example, a Valentine bean (Phaseolus vulgaris ‘Valentine’) will cross with a Dappled Grey bean (Phaseolus vulgaris ‘Dappled Grey’) because they are the same species. Neither will cross with a Phebe Vinson lima bean (Phaseolus coccineus ‘Phebe Vinson’) because they are different species. 2. Know the lifecycle Annual plants will complete their life cycle in one growing season, producing seed in one year. Biennial plants need two growing seasons, typically with an overwintering period, to produce seed. In the Midwest, biennial plants must be overwintered in root cellars to avoid winter cold damage. Common annuals: arugula, basil, beans, some broccoli, cilantro, corn, cucumber, dill, eggplant, lettuce, melon, some mustard greens, okra, pea, pepper, pumpkin, radish, spinach, squash, tomato, watermelon Common biennials: beet, some broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, celery, celeriac, Swiss chard, chicory, collards, kale, leeks, some mustard greens, onions, parsley, parsnip, radicchio, rutabaga, turnip 3. -

The Solanaceae

PHASEOLUS LESSON TWO The Genus PHASEOLUS and How to Grow Beans In this lesson we will continue our study of the LEGUME family by concentrating on the GENUS Phaseolus, We will study some of the different SPECIES in the GENUS Phaseolus. We will also study about growing beans. For this lesson to be complete you must: ___________ do everything in bold print; ___________ answer the questions at the end of the lesson; ___________ learn to identify the different beans (use the study materials at www.geauga4h.org); and ___________ complete one of the projects at the end of the lesson. Parts of the lesson are underlined and/or in a different print. These sections include reference to past Plant Masters projects. Try your best to answer using your old project books or your memory. Younger members and new members can ignore these sections. Parts of the lesson are underlined. Younger members can ignore these parts. WORDS PRINTED IN ALL CAPITAL LETTERS may be new vocabulary words. For help, see the glossary at the end of the lesson. INTRODUCTION TO THE Phaseolus Phaseolus - Bean Group The word “bean” is used for plants and FRUITS of many different GENERA. Originally it was used for the broad bean, or Vicia faba. However, when other bean-type FRUITS came from other parts of the world, the word was extended to the plants in several other GENERA. It is even used for the FRUITS of plants which are not “beans” at all. However, the FRUITS of these plants resemble beans, for example coffee beans, cocoa beans, and vanilla beans. -

Runner Beans Jacquie Gray Trials Officer, RHS Garden Wisley Dr Peter Dawson Vice Chairman, RHS Vegetable Trials Subcommittee Bulletin Number 19 October 2007

RHSRHS PlantPlant TrialsTrials andand AwardsAwards Runner Beans Jacquie Gray Trials Officer, RHS Garden Wisley Dr Peter Dawson Vice Chairman, RHS Vegetable trials Subcommittee Bulletin Number 19 October 2007 www.rhs.org.uk RHS Trial of Runner Beans Runner Beans BBC Gardeners’ World Garden (Berryfields), West Dean Gardens (West Sussex), RHS Garden Rosemoor (Devon) and (Phaseolus coccineus) RHS Garden Harlow Carr (North Yorkshire). Quality and In 2006 the Royal Horticultural Society, as part of a cropping data was requested from all sites and, when made continuing assessment of new and established cultivars for available, was included as part of the assessment by the cultivation, held a trial of runner beans. RHS vegetable Vegetable Trials Subcommittee. trials are conducted as part of our charitable mission to inform, educate and inspire all gardeners, with good, reliable cultivars identified by the Award of Garden Merit after a period of trial. Background Runner beans (Phaseolus coccineus) are also known as “scarlet runners”, a term that reflects the growth habit and Objectives red flowers of early introductions. Perennial, but not frost- hardy, they are usually grown as a half-hardy annual. The trial aimed to compare and evaluate a range of runner Members of the Fabaceae family, runner beans are native to bean cultivars, including short-pod and dwarf-growing the cooler, high-altitude regions (around 2000 metres) of cultivars, grown in different parts of the country, and to central and northern South America, where they have been demonstrate the cultivation of this crop. The Vegetable domesticated for more than 2000 years, although wild, Trials Subcommittee assessed the entries and outstanding small-podded plants are still found growing in the cool, cultivars for garden use were given the Award of Garden partially shaded valleys of mixed pine-oak forests in Merit. -

Morpho-Agronomic Characterisation of Runner Bean (Phaseolus Coccineus L.) from South-Eastern Europe

sustainability Article Morpho-Agronomic Characterisation of Runner Bean (Phaseolus coccineus L.) from South-Eastern Europe Lovro Sinkoviˇc 1,* , Barbara Pipan 1 , Mirjana Vasi´c 2 , Marina Anti´c 3 , Vida Todorovi´c 3, Sonja Ivanovska 4, Creola Brezeanu 5, Jelka Šuštar-Vozliˇc 1 and Vladimir Megliˇc 1 1 Crop Science Department, Agricultural Institute of Slovenia, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] (B.P.); [email protected] (J.Š.V.); [email protected] (V.M.) 2 Institute of Field and Vegetable Crops, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Agriculture, University of Banja Luka, 78000 Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina; [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (V.T.) 4 Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Food, ‘Ss. Cyril and Methodius’ University in Skopje, 1000 Skopje, North Macedonia; [email protected] 5 Vegetable Research and Developments Station Bacau, 600401 Bacău, Romania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +386-1-280-5278 Received: 2 September 2019; Accepted: 4 November 2019; Published: 4 November 2019 Abstract: In South-Eastern Europe, the majority of runner-bean (Phaseolus coccineus L.) production is based on local populations grown mainly in home gardens. The local runner-bean plants are well adapted to their specific growing conditions and microclimate agro-environments, and show great morpho-agronomic diversity. Here, 142 runner-bean accessions from the five South-Eastern European countries of Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, North Macedonia and Romania were sown and cultivated in their respective countries and characterised using 28 quantitative and qualitative morpho-agronomic descriptors for Phaseolus spp. -

RUNNER BEAN (Phaseolus Coccineus L.) – BIOLOGY and USE

Acta Sci. Pol., Hortorum Cultus 9(3) 2010, 117-132 RUNNER BEAN (Phaseolus coccineus L.) – BIOLOGY AND USE Helena abuda University of Life Sciences in Lublin Abstract. Runner bean (Phaseolus coccineus L.) is, after common bean (Phaseolus vul- garis L.), the second most important species, both around the world and in Poland. How- ever, as compared to common bean, runner bean was not so well recognized, which is in- dicated by reports from literature. Among the most important values of this bean species are large and very large seeds (the weight of one thousand seeds: 900–3000 g), which, with respect to their nutritional value rival common bean seeds. There are forms of it that differ in plant growth type, morphological features of flowers, pods and seeds, as well as in the manner of use – green pods and for dry seeds. On the basis of world literature, re- sults of the author’s own studies, as well as the studies conducted in Poland by her col- laborators and other authors, the issues of development biology, agrotechnical and envi- ronmental requirements, flowering and pollination of this allogamous species were pre- sented, as well as yielding, sensitivity to herbicides, effect of pathogenic factors upon generative organs, as well as chemical composition of runner bean seeds and pericarp (Phaseoli pericarpium). Key words: runner bean, cultivars, flowering, pollinating insects, yield, use, dry seeds, harvest INTRODUCTION The seeds of leguminous plants, including bean, have high (more than 20%) con- tents of protein with high biological value, carbohydrates – including fibre, mineral salts – potassium, phosphorus, magnesium and calcium, as well as vitamins from group B. -

Flowering Vines for Florida1 Sydney Park Brown and Gary W

CIRCULAR 860 Flowering Vines for Florida1 Sydney Park Brown and Gary W. Knox2 Many flowering vines thrive in Florida’s mild climate. By carefully choosing among this diverse and wonderful group of plants, you can have a vine blooming in your landscape almost every month of the year. Vines can function in the landscape in many ways. When grown on arbors, they provide lovely “doorways” to our homes or provide transition points from one area of the landscape to another (Figure 1). Unattractive trees, posts, and poles can be transformed using vines to alter their form, texture, and color (Figure 2).Vines can be used to soften and add interest to fences, walls, and other hard spaces (Figures 3 and 4). Figure 2. Trumpet honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens). Credits: Gary Knox, UF/IFAS A deciduous vine grown over a patio provides a cool retreat in summer and a sunny outdoor living area in winter (Figure 5). Muscadine and bunch grapes are deciduous vines that fulfill that role and produce abundant fruit. For more information on selecting and growing grapes in Florida, go to http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ag208 or contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office for a copy. Figure 1. Painted trumpet (Bignonia callistegioides). Credits: Gary Knox, UF/IFAS 1. This document is Circular 860, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date April 1990. Revised February 2007, September 2013, July 2014, and July 2016. Visit the EDIS website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. 2. Sydney Park Brown, associate professor; and Gary W. -

Southern Garden History Plant Lists

Southern Plant Lists Southern Garden History Society A Joint Project With The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation September 2000 1 INTRODUCTION Plants are the major component of any garden, and it is paramount to understanding the history of gardens and gardening to know the history of plants. For those interested in the garden history of the American south, the provenance of plants in our gardens is a continuing challenge. A number of years ago the Southern Garden History Society set out to create a ‘southern plant list’ featuring the dates of introduction of plants into horticulture in the South. This proved to be a daunting task, as the date of introduction of a plant into gardens along the eastern seaboard of the Middle Atlantic States was different than the date of introduction along the Gulf Coast, or the Southern Highlands. To complicate maters, a plant native to the Mississippi River valley might be brought in to a New Orleans gardens many years before it found its way into a Virginia garden. A more logical project seemed to be to assemble a broad array plant lists, with lists from each geographic region and across the spectrum of time. The project’s purpose is to bring together in one place a base of information, a data base, if you will, that will allow those interested in old gardens to determine the plants available and popular in the different regions at certain times. This manual is the fruition of a joint undertaking between the Southern Garden History Society and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. In choosing lists to be included, I have been rather ruthless in expecting that the lists be specific to a place and a time.